As a short follow-up to my long post on the Eroica Marcia funebre, I thought I might mention a little bit about Metamorphosen, Richard Strauss’s late masterpiece mourning the end of the great and continuous musical culture that ran from Bach through to him.

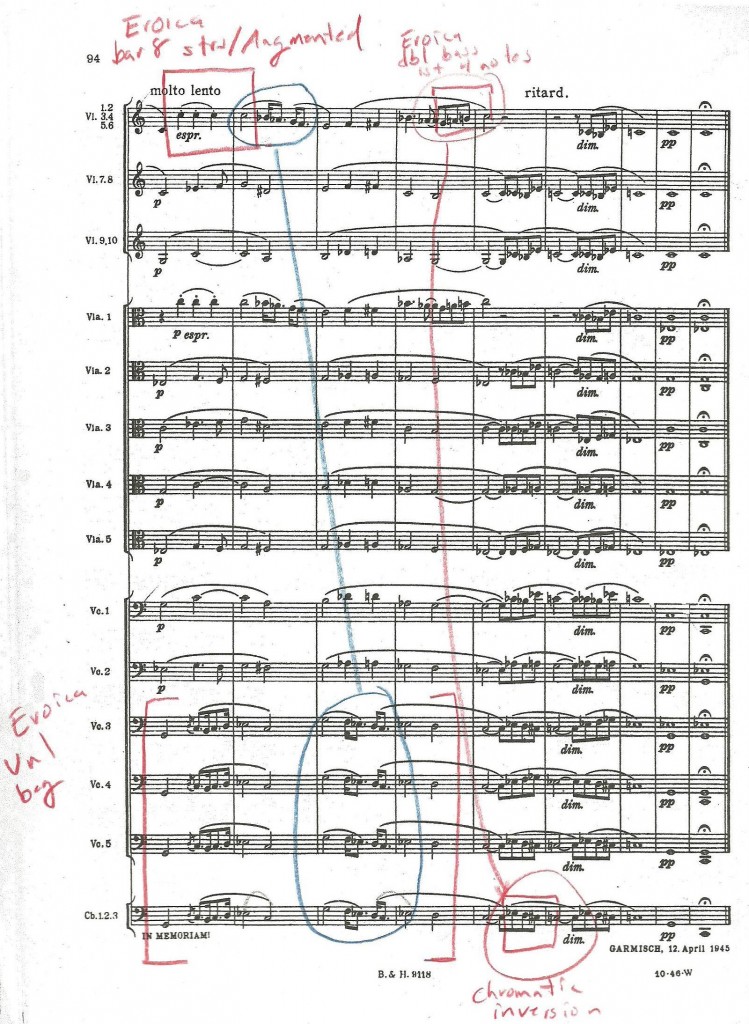

On the final page of the score, Strauss quotes the opening of the Beethoven Funeral March to devastating effect, with the words “IN MEMORIAM!” underneath. In retrospect, one can see that almost all of the material in the entire work is extracted in one way or another from this quotation.

Such an analysis is too big a project for me today, but just a quick look at this one page is a tremendous object lesson in how a great composer uses a shout-out or quote to create layers of meaning.

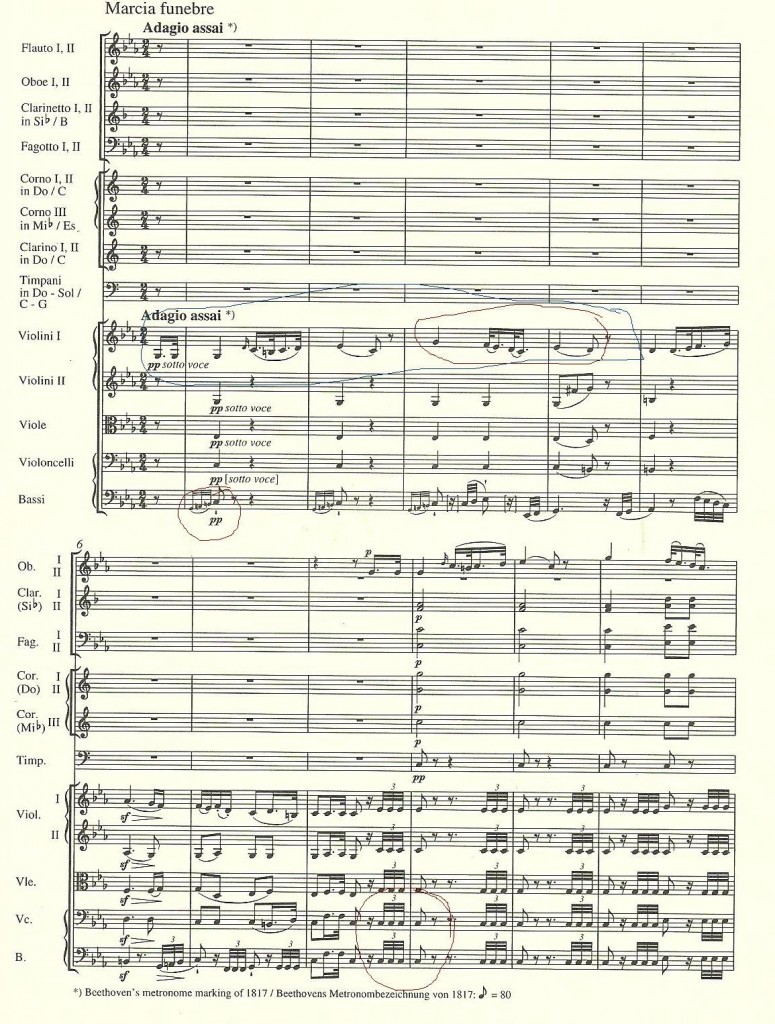

As if Beethoven’s original is not bleak enough, Strauss goes to some lengths to create a rendering of the material that is even more despairing and hopeless. First, he transfers the melody from the 1st Violins, the top of the orchestral sonority (although they start on their own lowest note) to the bottom of the strings- the double basses and the last three solo celli. It’s as if he’s flipped the musical picture upside down.

6 bars before the end, the top violins and 1st viola end their counter-melody with a direct quotation of the basses 1st three notes from the beginning of the Eroica Marica funebre. Again, it is as if Beethoven’s world is literally being turned upside down. There is at least a sense of order and ceremony in Beethoven’s lament- in the Strauss, that structure is gone.

Then look at the beginning of the violin theme on the top of the page- those three C quarter notes are simply an augmentation of the triplets in the 8th bar of the Beethoven. Again, the pitch, C comes from double basses- Strauss turning the ordered world of Beethoven upside down in yet another way. These three C’s are one of the keys to understanding the whole motivic structure of the piece. The relationship of the 2nd bar on the page to the Eroica is obvious (see the blue circles below), but the origin of these 3 quarters is more hidden, and yet they permeate the entire work.

And what of those last five bars? Notice how Strauss takes the 4-note idea from the opening of the Beethoven, which he quotes not in the basses, but in the violins, and restores it to the cellos and basses. Rather than give the bass instruments what ought to rightly be theirs, he inverts the theme and spells it as a chromatic rather than diatonic scale. Not has his world been turned upside down, it has literally been crushed down from whole steps to half steps.

The ending of this piece is devastating on its own terms, but when you understand even a few little bits of the layers of reference, comment and meaning that Strauss has encoded into the score, it’s almost unbearable. The dialogue between the Beethoven and the Strauss works is bound to affect our perception of both works.

Recent Comments