Composer Aldo Clementi passed away last week at the age of 85. There have been nice tributes at The Rambler , Ravishdears and Boulezian.

I came into professional contact with his music only once- we recorded two of his early works, Ideogrammi I and Ideogrammi II, with the Contemporary Music Ensemble of Wales for Radio 3’s Hear and Now. I think Clementi’s aesthetic mellowed a bit with time- these two works are out on the extreme edge of Darmstadt-esque high-modernist hyper-complexity. They were fun to work on, but with changes of tempo and meter in almost every bar, I had to spend a fair bit of time just figuring out mathematically reliable ways of getting the proportions right, then checking my methods against the metronome again and again, bar by bar. The pitch language is similarly uncompromising- we found one wrong note in the score simply because of the illegal presence of an octave.

Since we basically had one session in which to rehearse and record the two Ideogrammi’s, there would be no time for them to simmer and settle. Some of the transitions look close to impossible, and they are so close together that it’s hard to imagine how any group of musicians could navigate them all without extended rehearsal. In fact, there are stories of spectacular train wrecks at early performances (as there is for most music of this era). Given the situation, our producer called me and suggested we sit down with the score and divide the piece into manageable chunks and just record bit by bit, rather than try to “solve” all the transitions.

This may sound like cheating, but a lot of CDs of far more standard repertoire are done in this same way- some conductors and producers never do a complete take of a movement, or leave the complete take to the very end. What was a little unusual, but probably prudent, was to plan in advance how we were going to chop the thing up in order to put it back together.

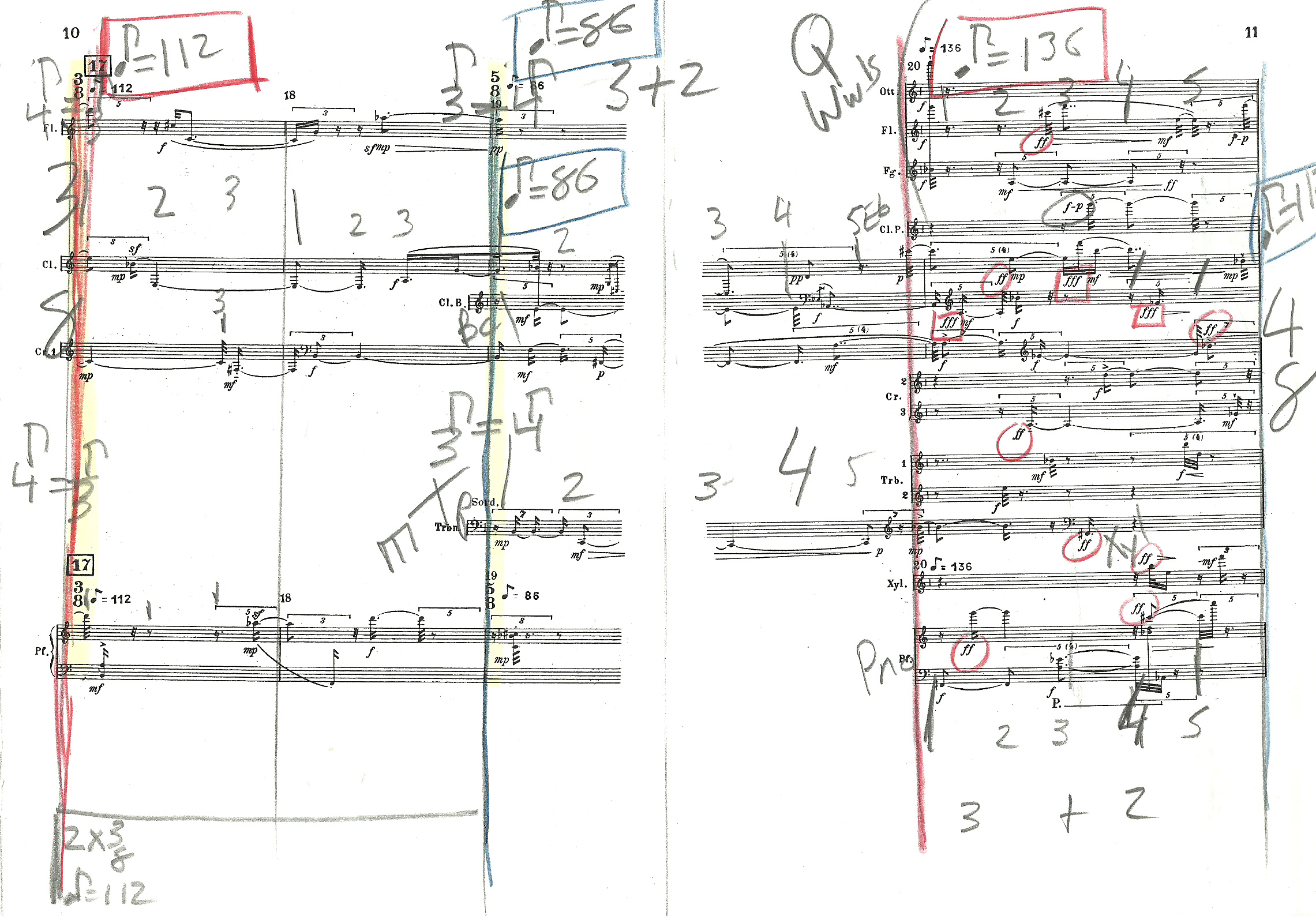

Like a lot of contemporary music, Clementi’s notation and the style in which it is printed make things more challenging. What some call “open format” scores, in which empty bars are just left as white space on the page, can be a lot harder to read, especially when things are spread across the page. If you look at the sample page of the score, you’ll see I’ve remarked a few things- extended bar lines vertically through the whole page, marke the beats, highlighted some dynamics. The metronome marks are invisible from four feet away going at speed (the scan below was originally 1 side of an A4 sheet, about 8/11.5 inches). Where I marked 86 twice was the result of my realizing my eye needed it lower on the page at that moment. Things go by so fast there is no time to hunt for information on the tiny page. You’ll also notice how bar 19 stretches across two pages. That doesn’t make it easier to read!

Anyway, my mind was very focused on the practicalities of it all before the sessions. The notion of “interpreting” a piece like this, at least on limited rehearsal time, is pretty silly. In this music, your job is far more practical- you really are there to beat time and get everyone playing the right thing at the right moment.

Even stopping every single bar, you can only play this music if everyone in the group is incredibly good and incredibly prepared. This is most certainly the case in the Contemporary Music Ensemble of Wales.

It got interesting in the sessions. We made a start on Ideogrammi I and were working our way through as planned. We sort of explored in awkward and stumbling steps once from beginning to end, stopping every time a corner needed explaining or avoiding, then started working, recording and patching our way through.

We weren’t too far into this process when something unexpected happened. We made it past one of our pre-determined edit points. A take or two later, we passed one, then two so I just kept going. Suddenly, we had a nearly complete take of almost the whole piece. The players were so well prepared, and I had put in so many gazillions of hours studying and metronoming that we could actually play the damn thing, which had probably needed 30 rehearsals in 1960, after only about 45 minutes rehearsal.

Then, something even nicer happened. We’d been patching a few little chunks, then did another long take, and when we got to the end, I felt a strange mixture of catharsis and transformation. The piece had actually moved me. Maybe I was just relieved to get through it! No- I think I was moved. My surprise was not the result of my coming in thinking it wasn’t a good or effective piece- I’d just been so intently focused on doing my job that deeper musical considerations hadn’t really been on my radar. It hadn’t really occurred to me to wonder whether it would move me or not. I just didn’t want to, er, f*ck it up. We moved on to Ideogrammi II that afternoon with much the same result, although one of our stricter modernistas was offended by the use of saxophones. I actually found it even more moving and impressive. It’s an amazing showcase for the solo flautist, in this instance Christopher Green.

I still find the end of Ideogrammi II is very haunting- lonely and austere. Like a cold night alone in a concrete landscape.

So, that’s my Aldo Clementi story- what once looked and sounded almost completely impossible and possibly pointless turned out to be playable and rather nice. Even great. Imagine….

Anyway, in memory of Clementi, here, for a limited time, is a bit of Ideogrammi II from our recording.

Copyrighted material is excerpted on these pages without profit for educational purposes only under Fair Use provisions of relevant copyright law and will be removed on request. In all instances, copyright is owned and maintained by the original copyright holder.

Recent Comments