The composer Felix Mendelssohn made many visits to the British Isles during his short life, yet it is little known that he stayed in North Wales for several weeks in 1829, visiting many of its famous beauty spots. But fact can indeed prove stranger than fiction, since few would guess that his presence in Wales would one day connect him with one of the great Victorian works of children’s literature and Britain’s production of chemical weapons during World War II. Here Peter Davison explores a web of connections which reveal how history and culture, time and place can often be extraordinarily intertwined:

Incongruities are a commonplace in our contemporary world, because our values are uncertain and we look back at certainties of the past with some envy. Modernity can be ruthless towards our heritage. A bypass carves its way through some green countryside or some ugly skyscraper obscures an architectural masterpiece. Such contrasts provoke discomfort – rather like seeing a moustache drawn on the Mona Lisa; a thoughtless violation of good taste carried out in the name of progress. Yet the past can also be a tyranny – where wounds never heal, grudges become ingrained and change is stubbornly refused. The new can certainly help us to bury the past or build upon it constructively. We are in a creative tension with those who came before – in awe of them – admiring what they did and with what conviction they have believed. We treasure their legacy, but must not be hostage to it.

Awkward historical juxtapositions can be instructive, because they show us our ambiguous response to the past. I had this experience in an unprepossessing corner of North Wales the other day. I was in a small village called Rhydymwyn on the main road between Mold and Denbigh. It is a quiet place set among low wooded hills, surrounded by flowing streams and lush farmland. You would probably not stop there under normal circumstances but, if you did, you would find a modest plaque on a wall which states that, in this valley in1829, the composer Felix Mendelssohn stayed as a guest of an industrialist called John Taylor at nearby Coed Du Hall. It was here that Mendelssohn composed Three Caprices for piano to entertain Taylor’s daughters. Two of the works were inspired by the flowers growing in the fields around the house, while a third, known as “The Rivulet”, depicted the flow of the picturesque River Alyn – otherwise known as the Leete – which passes through Rhydymwyn. The same plaque tells us that Charles Kingsley, author of the 1863 children’s classic, The Water Babies, also frequently walked in the vale, albeit some years later.

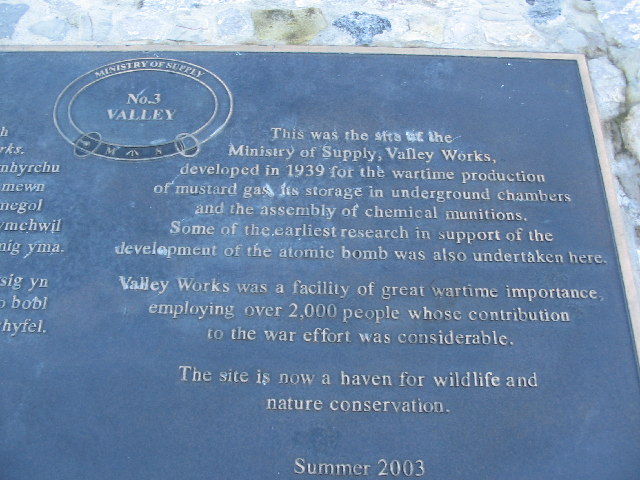

This plaque looks inconsequential, but it hints at an extraordinary web of unlikely connections which has Rhydymwyn at its centre. Most controversially, in 1939, at the start of the Second World War, when the village still had a railway, a huge factory complex was built there by the government. The complex was to be the site of Britain’s first chemical weapons’ testing programme and also a major centre for research into the possibility of atomic warfare., ICI , the company which manufactured mustard gas for addition to standard shells, was based not far away in Merseyside. Moving nasty substances the thirty miles to Rhydymwyn was thus quick and cheap to do. It was in this very network of buildings, tunnels and bunkers where the mustard gas canisters were tested. In addition, top scientists were gathered there to research the possibility of making an atomic bomb. While no weapon was ever developed at the site, much of the research carried out was handed over to the American scientists working on the Manhattan project.

The factory complex has long since become disused and is now a Nature Reserve. While many of its buildings remain, there is evidently no threat to public health and, over time, this sorry phase in the history of Rhydymwyn will no doubt be forgotten. But it is sobering to realise that such dark deeds were carried out right next to the same serene waters, green fields and steep wooded banks which had inspired Felix Mendelssohn’s music and Charles Kingsley’s imaginative story of social conscience. Where they had found beauty and hope, child-like wonder and tranquillity, a century later and this innocence had been lost. Weapons of mass-destruction were being created, tested and planned just a few hundred yards away. It reminds me that Goethe’s favourite oak tree, where he had conceived many idealistic and creative thoughts, ended up inside the confines of Buchenwald concentration camp. The tree was a justified casualty of American bombing, but such incongruities tell us just how morally bankrupt European culture had become after two centuries of so-called enlightenment.

While the contrast could not be more marked between the creative artist and the munitions factory, there are perhaps some seeds of that grisly future lurking in the background of Mendelssohn’s visit to Coed Du and Kingsley’s famous book. Mendelssohn’s host, John Taylor was a mining engineer, and the whole area around Rhydymwyn is riddled with quarries and open mines, some of them still working today. These appear like great stone gashes in the hillsides. Huge lorries rumble along quiet lanes filled with precious rock. The sound of large explosions can be heard from time to time disturbing the peace. Indeed, mining and quarrying have been undertaken in that part of Wales for hundreds of years, and the weapons’ centre was itself built on the top of old mine-workings. Mendelssohn we know was taken to meet some miners and picnicked with them. We can conclude that despoiling the land for profit was happening back then, much as it is now, and many became rich from it. Yet Mendelssohn could still idealise the landscape in his music without any sense of irony. The full consequences of the industrial revolution and its associated technological developments were not known in his day. Industrialisation was a brave new world, harnessing Nature’s resources for Man’s progress and well-being. Those at the cutting-edge of these developments, like John Taylor, were optimistic, affluent men, well-placed to value and support someone with Mendelssohn’s creative gifts.

Charles Kingsley shared much of this optimism about the future with Taylor. In The Water Babies, the fallen waif, Tom, is redeemed through faith. His life is turned around so that he is able to become “a great man of science” who “can plan railways, and steam-engines, and electric telegraphs, and rifled guns, and so forth”. For the Victorians, science and religion together could transform society’s losers into winners. It seems a reasonable proposition, but its naivety would be dramatically revealed when, less than a hundred years later, the full consequences of industrialisation, especially in the field of weaponry, had become visibly monstrous. Mendelssohn’s little Caprices for piano suddenly seem banal in this context, just as Kingsley’s optimistic narrative does. The 20C demanded a much more brutal musical sound-track and a more gloomily realistic narrative. Not surprisingly, after such heady idealism and happy delusion, what followed felt ironic; a beautiful dream which had turned into a terrible nightmare.

There is yet more to this. Charles Kingsley had read an advance copy of Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859). Rather against the tide of opinion among the clergy, he was open to many of its ideas, but in The Water Babies (1863), he chose to satirise those who interpreted it too dogmatically or as an anti-religious text. He could perhaps foresee the dangers, if these new ideas were taken too far, and he was right. The Nazis used Darwin to give their sense of racial superiority a spurious scientific justification. Yet The Water Babies reveals just how complex such matters can be, as it casts casual aspersions on Jews, Blacks, Catholics and the Irish. Even an enlightened Christian man like Kingsley could not escape the prejudices of his age. He believed that white Protestants like himself were naturally superior to all others. Perhaps the lesson which Rhydymwyn teaches us is that all societies have blind-spots, and it is only when these lead to catastrophic consequences that those failings are finally recognised. Real human progress is hard won – not by technological advancement and naïve optimism, but by the hard lessons of experience and history.

But there is one more strange connection. In The Water Babies, Kingsley also satirised the famous controversy between Owen and Huxley known as “The Hippocampus Question”. In a nutshell, this was a discussion derived from Darwin’s Theory of Evolution. Owen disputed that there was no evidence of any similarity between the brain of the gorilla and the human being, while Huxley argued that the human brain was obviously similar in origin. Kingsley mocked both sides, calling the debate “The Great Hippopotamus Question”. This concern with what makes our brains work and how they have developed may seem like a side-show, until you realise that the house where Mendelssohn had stayed in the 1829, Coed Du Hall, is now a private hospital for people with serious brain injuries and mental disabilities.

It is an unusual property of the River Alyn that in dry spells it disappears underground, filling the intricate network of caves and dark passages beneath your feet. After a period of heavy rain, the river soon resurfaces and becomes once more the chattering brook of Mendelssohn’s “The Rivulet”. That might be a metaphor for the history of Rhydymwyn, which is at first glance like many other Welsh villages but, which has in fact gathered around it striking examples of mankind’s Faustian contradictions. Visions of beauty, social conscience and healing have emerged side by side with ugly and horrific interventions in Nature. If you are ever in that part of the world, why not take a look. What a story it has to tell! Two centuries of dramatic history, asking the central questions of European culture are hidden there, while its river flows on and on, even if occasionally it seems to disappear.

What a delightful piece about Rhydymwyn, incorporating Music, History, Literature, Nature and Geography. I walk ‘the leete’ daily with my dogs, it is beautiful and peaceful with an abundace of wildlife, if I did not live here I would be inspired to visit.

Dear Patricia, thanks for your kind words – I stroll that valley too from time to time, although I live on the other side of the River Dee, and it is a true hidden gem full of fascinating history.