This is a slightly expanded version of an essay on Brahms’s last symphony commissioned by The Bridgewater Hall for last week’s Budapest Festival Orchestra concert.

“But in dark, dramatic outbursts such as those in the first and last movements of his Fourth Symphony, something apocalyptically grandiose and superhuman takes place. He had outgrown the passionately romantic extravagance of subjectivity; free from illusions, he could now face the world from the remote viewpoint of a stoic, without illusions and without self-pity.”

Hans Gál- Johannes Brahms, His Work and Personality

Brahms

One might be tempted to call the tragic symphony the white tiger of musical genres. Of all musical species, it is one of the most fascinating and powerful, yet sightings are rare. Between the two greatest specimens, Mozart’s 40th and Mahler’s 6th, one finds precious few examples. Beethoven never wrote one, and neither did Schumann, Bruckner, Dvorak or Schubert. If the 19th c was the golden age of the symphony, the lone great tragic essay in the genre was Brahms’s Fourth.

Brahms tended to create works in sharply contrasting pairs- as if the second work, almost always diametrically opposed in mood, might act as philosophical counterargument to the first. This tendency is already apparent in his first two opus numbers, the Piano Sonatas in C major and F-sharp minor. In that case, as in the later pairing of the Academic Festival Overture with the Tragic Overture, the second work feels like a negation of the exuberance of the first. This was not always the case- the Second Piano Quartet in A major feels like a well-earned vacation in a sunny climate after its stormy predecessor in G minor. In the case of his opus 51 String Quartets, both are in minor keys, but the first is Beethovenian and extrovert, the second more intimate and full of reminiscences of his intimate circle of friends, including the Schumann’s and Joachim.

Thus is was that after the seventeen year gestation that preceded his First Symphony, a most Beethovenian work of taut arguments and heroic struggle, in 1876, its antipode, the lyrical and pastoral Second came only months later. And yet these two works are made of much the same musical DNA- the neighbour-tone gesture which forms the main motive of the Finale of the First becomes the first three notes of the first and last movements of the Second.

Brahms knew that his First Symphony would be compared with those of Beethoven- it was quickly nicknamed “The Tenth” and commentators were keen to point out the similarities between the big tune in Brahms’s finale and the Ode to Joy in Beethoven’s Ninth. “Any idiot can spot that!” was Brahms’s impatient retort. Later commentators have noted that Brahms’ First Symphony can be seen as both an homage to and a critique of Beethoven’s Ninth. Yes, the parallels are obvious, but it was no accident that Brahms did not include Beethoven’s janizary band and chorus, and even less of an accident that Brahms ended his symphony not with the “big tune,” as Beethoven did, but with that that tight little three-note motivic cell. Beethoven’s last symphony ends with an apotheosis of ecstatic song, Brahms First ends with a reassertion of Classical rigour and symphonic logic.

In many genres, Brahms’ was content to let a pair stand- thus we have two sextets and two overtures. In other cases, Brahms returned later to the genre with a mediating third work, as with the piano sonatas, the string quartets and the piano quartets. In each case, this third work seems to bridge some of the differences and settle the philosophical argument between the first two pieces.

http://youtu.be/H8Z8lauIao0

(Big, bad, Bernie Haitink brings it to Brahms 4 with the COE)

And so it looked to be in the case of the symphony when Brahms composed his Third Symphony five years later in 1882. The connections with the two earlier symphonies are profound- the Finale in particular is a working out of the same neighbour tone motive that had been so central to the two previous symphonies. And, as expected, it seems to embrace both the storminess and tautness of the First (particularly in the outer movements) and the lyricism of the Second (the two inner movements and the coda of the Finale). Even the mode of the Third seems to be straddling the worlds of the first two symphonies- it is a major key symphony that spends a huge amount of time in the minor. The last page of the Third seems to offer a sense of reconciliation and resolution. That he chose this piece to incorporate his musical motto, “Frei aber froh” (“free but happy”) makes its peaceful and reflective ending seem all the more touching. Life, he seems to be saying, is a struggle, like the First Symphony, but one can eventually find one’s way to the peace of the Second.

So, is it a surprise that in the case of the symphony, the peace did not hold? Once again, Brahms felt compelled to counter his own argument, to question what he’d just said. Less than a year after the premiere of the Third, he was hard at work on its antipode. On the surface, the Fourth seems the most Beethovenian Brahms symphony since the First, and yet Brahms was making a statement, devastating in its finality, that marked a complete departure from Beethoven’s absolute insistence that the answer to the fundamental symphonic question must always be “yes.”

Brahms wrote the bulk of the Fourth in the summer of 1884 in Mürzzuschlag. “The cherries don’t ever get to be sweet and edible in this part of the world,” he said, adding that something of their bitter flavour was to be found in his new symphony. When Brahms unveiled the work, some of his supporters found it “difficult,” and not only because of the tragic ending. Hanslick said listening to the first movement played through by two pianists was like “being given a beating by two incredibly intelligent people.” However, its premiere by the Meiningen Orchestra under the direction of Hans von Bülow was a triumph, and it soon became one of the central works of the symphonic repertoire.

The Fourth was a summation of Brahms’s work as a symphonist, in which his obsessions with unity, clarity, balance and proportion all found their culmination. Brahms’s favourite interval was the third, and in the Fourth he uses it as both a melodic and tonal building block- key relationships are, as so often in his music, expressed in thirds, but also the entire melody which opens the first movement is built on a chain of thirds. For much of the 20th c, conductors of Brahms’s music favoured sonority over all else, which has often left his rhythmic innovations overlooked. In the case of the Fourth, that is a great pity- Brahms’s is taking the rhythmic possibilities of the Romantic-era musical language to an extreme of sophistication and complexity that is perhaps unique. One passage in the first movement is so rhythmically multi-layered that composer Gunther Schuller says of it that “there is nothing like it even in the Rite of Spring.”

The first movement of Brahms’s previous minor-key symphony, the First, had already hinted at a light at the end of the tunnel, ending quietly and in the major. Not so in the Fourth, whose first movement concludes in full Sturm und Drang intensity. What follows is a masterstroke. He moves via a short C major introduction (very much a third away) from E minor to the E major denied us in the Allegro for a slow movement of breathtaking beauty and serenity. The last cadence brings the movement full circle- we arrive at the E major chord not from the dominant, but from the C major with which the movement began.

This final cadence is no mere harmonic felicity, but a gesture of profound structural importance as it not only creates a link with the end of the first movement, but with the Scherzo in C major which is to follow. This movement represents an explosion of vitality and life force unmatched in Brahms’s symphonic music (the only orchestral music of similar brilliance and exuberance is the Academic Festival Overture, which shares both the key of C major and Brahms’s use of triangle). All of Brahms’ previous symphonic third movements had been intermezzi of one kind or another, understated and intimate. This one sounds like the triumphant end of a symphony. When the work was premiered, Brahms and von Bülow risked the wrath of an otherwise ecstatic audience by refusing to encore it.

If the Fourth is a summation of everything Brahms was as a symphonist, this is most apparent in the Finale- the most original, perfect and powerful movement he ever wrote. Brahms had a love and understanding of Baroque forms unlike any other 19th century composer, surpassing even Mendelssohn’s depth of knowledge. For years, Brahms would wait eagerly for the newest volume of the Bach Gesellschaft to arrive in the post, and take it immediately to the piano to devour and internalize each of the Master’s works as they came back into print. His penchant for the Passacaglia as a form had already borne fruit in the last of the Haydn Variations- the crowning achievement of his first mature orchestral work. Now he returned to this ancient form, a perpetually evolving series of variations over a repeated bass, as the crowning glory of his life’s work.

His passacaglia theme is adapted from Bach’s cantata Nach dir, Herr, verlanget mich, BWV 150 (“For Thee, O Lord, I long”). Brahms immediately establishes that we are in a totally different world of emotion from the Allegro giocoso- back in E minor, and an atmosphere bitter as those Mürzzuschlag cherries. These last two movements themselves form a perfect Brahmsian antipodal pair, the unmatched triumph of the Scherzo swept aside by the high tragedy of the Finale.

Is it a step to far to compare the two pairs of pairs of Brahms symphonies? In the pair of symphonies from the 1870s, the First begins with Beethovenian struggle, breaks through into triumph then is followed by the autumnal serenity of the Second, which feels like a great reward for the hardships overcome in the First.

And yet his second pair of symphonies, from the 1880’s, seems to offer a negation of both their predecessors. The Third is full of struggle but ends in poignant acceptance, but acceptance of what? Seen in the light of the Fourth, the ending of the Third seems less like “reconciliation and resolution” and more like resignation. The presence of his motto on the last page of the Third hints that it is acceptance of himself and his destiny. But one also senses that he felt that the Fourth was his destiny- the piece he was meant to write. Although he’d stayed absolutely faithful to certain elements of Beethoven’s aesthetic, Brahms’s symphonic journey ends not with the Heaven-storming exultation of the giant whose footsteps he had always heard behind him, but with terrifying finality. It’s probably not an accident that the passage most similar in character to the last page of Brahms’ last symphony was the first page of his First. As always with Brahms, the end was in the beginning.

c 2013 Kenneth Woods

What an excellent essay through and through – a fascinating read, and now I’m overwhelmed with a need to hear this symphony again, one of my favorites since I was a teenager.

Two thoughts:

“One passage in the first movement is so rhythmically multi-layered…”

Can you describe where this is? I don’t actually have a score, but I respond well to descriptions like “the bit of the development where this happens.” Thanks!

Second: about the lack of tragic symphonies in the romantic era. (I’m not going to order you to hear Kalliwoda’s Fifth. Oh never mind. Yes I am. Listen to Kalliwoda’s Fifth.) When I was a youngster and put on Dvorak’s Seventh for the first time, it more or less traumatized me. It was incredibly dark and brooding, and the ending seemed to me as apocalyptic as a mushroom cloud.

It wasn’t until years later that I read a booklet essay to a CD that said that Dvorak’s Seventh had a triumphant ending. I thought, “What?!?” and put it on again and was ready to acknowledge that, yes, it ends in a major key, but could anybody really believe it was happy? Now I know of a few recordings which successfully bring off the idea of victory, but they don’t interest me like the ones where the symphony seems to be accepting its own doom.

All this is more interesting because, even if Dvorak did intend a “happy” ending, he doesn’t even hint at it until the final 45 seconds – and he and Brahms were composing their tragic symphonies at almost the same time, independently of each other’s work.

Anyway: great read. And I’ve put on Kubelik’s Brahms Fourth to usher in this Sunday morning.

Hi Brian

Interestingly, I wrote a whole half-paragraph about Dvorak and the tragic symphony that I ended up cutting. Basically, I agree with you about the Seventh, although I also think the major-key ending, while not exactly happy or triumphant, is a very different thing from the endings of Brahms 4, Mozart 40 and Mahler 6, which are shockingly final. Dvorak seems to be finding a tone at the end of the Seventh and the New World, which is very much a dark and tragic piece, that anticipates something one finds in later Slavic symphonies, especially Shostakovich- the idea of triumph at a high price. There is a sense of final success in the last bars of Dvorak 7 and 9 as there is in Shostakovich 5 and 7, but the hero is beaten and bloodied, and the price paid is horrifically high.

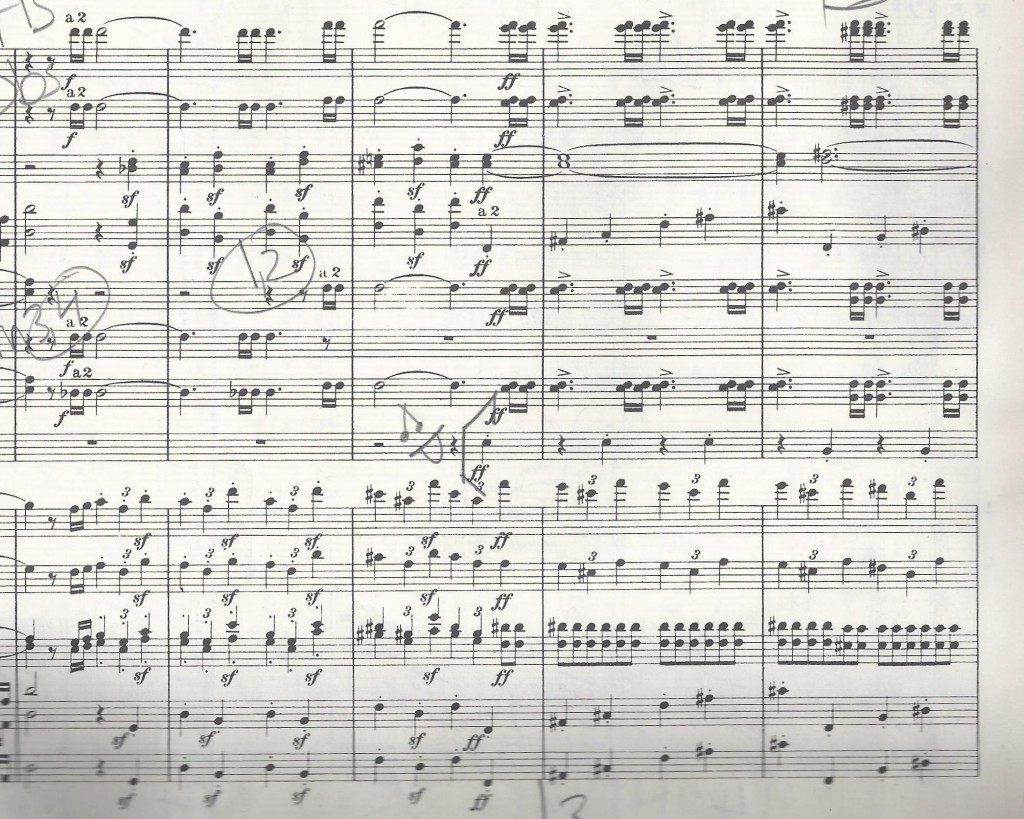

I’ve added a scan of the Gunther Schuller memorial passage above. It is tricky to get right.

Thanks for reading and for the very kind comment. Off to check out Kalliwoda….

I’m surprised nobody has mentioned Tchaikovsky’s 6th symphoniy, i’ve always considered it one of the most tragic symphonies.

It seems to the listener that the first three movements are built on descending harmonic sequences, while only the finale has an ascending progression at its core. So you are subconsciously prepared for the tragic denouement by a sort of ironic narrative paradox – the elegy comes before its cause.

Great essay!

Does Tchaikovsky’s 6th not qualify as a nineteenth-century “tragic” symphony? Certainly the first and last movements are largely or totally tragic (the first movement energetically and the finale resignedly), and the wistful second movement (the “broken waltz”) has tragic elements. Only the third movement partakes of triumph, but the third movement of Brahms’s Fourth does so as well…