For me, it was musical love at first sight. The first time I heard the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto was on a cassette tape. I loved it so much, I kept rewinding and replaying bits of the first movement (most often the big tutti at the end of the exposition- even then I had conductor tendencies). It must have taken me the better part of 2 hours to listen to get to the end of the first movement the first time I listened to it. I was hardly new to Tchaikovsky- I’d imprinted on the Fifth Symphony and Romeo and Juliet at a very young age. But the Violin Concerto struck me as very special from the first time I heard it.

And since then, I’ve heard it and heard it and heard it. I’ve played it in orchestra a gazillion times. I’ve conducted it many times. I’ve heard performances that ranged from astounding to atrocious.

I suppose these days, it has true warhorse status- every serious violinist has learned it. One could walk the hallways at the IU School of Music when I was a student and hear 35 people practicing it at once- and almost all of them playing it damn well.

And yet, the piece remains a curiously high risk work of art, one that somehow seems to confound many performers. How can such a well-known masterpiece still be performed regularly with cuts that Tchaikovsky abhorred and which only weaken the structure of the work?

It is the nature of a such a famous piece that it will ultimately be heard in all manner of performances, good and bad, but I can’t help but feel that it gets more than its fair share of the bad. Somehow, in spite of those many performances which fall into the obvious traps (sensationalistic, routine, competition-ish), the piece survives in the hearts of music lovers worldwide.

About the piece

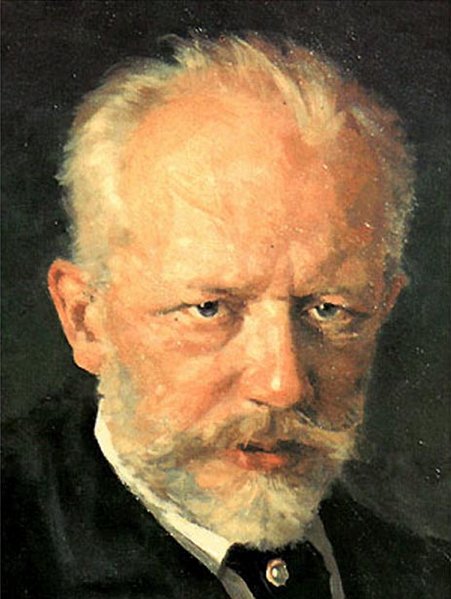

Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky

(1840-1893):

Violin Concerto in D major, opus 35

1877 was the year of Tchaikovsky’s disastrous marriage to Antonia Milyukova, a former student who made so little impression on him that he couldn’t even remember when he received her first love letter. The marriage only lasted a few months, but drove Tchaikovsky to a botched suicide attempt. Rescued from the situation by his brother Anatoly, Tchaikovsky seemed to recover his focus and inspiration rather quickly. In the early months of 1878 he completed the two works he’d been working on before his marriage: the Fourth Symphony and Eugene Onegin. Shortly thereafter he had a visit from another former student, and likely past (and possibly current) lover, the violinist Yosif Kotek. The two played through Lalo’s Symphonie Espagnol, and Tchaikovsky was struck by the work’s freshness, and Lalo’s willingness to avoid the sobriety he associated with German essays in the genre. Tchaikovsky quickly set to work on his own Concerto, working closely with Kotek, who learned the violin part as Tchaikovsky wrote it and helped advise the composer on writing for the violin. Progress on the Concerto was swift, and the work was finished within a month. In the end, however, it was not to be Kotek who would bring the work to life. Tchaikovsky dedicated the new Concerto to Leopold Auer, then the leading violin soloist and pedagogue in Russian musical life. A premiere was planned for March 1879, but Auer pulled out, reportedly dismissing the Concerto as “unplayable” (Auer later firmly denied saying this) Tchaikovsky was devastated, humiliated, and the concert was cancelled.

It took another two years for the work to find a first performance, but this was not to be a happy occasion for Tchaikovsky, either. A young, relatively unknown violinist named Adolph Brodsky learned the piece and organized a performance with none other than the Vienna Philharmonic and conductor Hans Richter. Not only did the concert go poorly, it drew one of the most vituperative reviews in all music history from the influential critic Eduard Hanslick. Hanslick said of the piece that it was music “whose stink you can hear.” Tchaikovsky never forgot that review and could quote it word for word until the end of his life.

(The 75-year-old Leopold Auer shreds some Brahms)

Auer was eventually shamed into learning the Concerto, and became an important advocate for the piece, although his legacy remains decidedly mixed. To his credit, he performed the piece many times, and, perhaps more importantly, taught it to some of the greatest violinists of the new century, including Jascha Heifitz, Nathan Milstein, Mischa Ellman and Efrem Zimbalist. On the other hand, Auer insisted on making his own “version” of the work, which he taught to his many students, rewriting several passages and introducing many cuts in the score, and, sadly, many of these changes continue to appear in performances of leading violinists to this day. Auer’s changes are worse than unnecessary – they represent a major defacing of a great work of art, and a strangely enduring defacing at that.

Performance practice

I’ve already pointed out that Auer’s cuts and rewritings to the Violin Concerto constitute a very regrettable stain on that great violinist’s reputation. Nevertheless, we should remember one thing about Auer’s role in the genesis of the Concerto: while the piece was inspired by Tchaikovsky’s fling with Kotek, and although Brodsky would be the one who brought the piece into the world at last, while writing the work, Tchaikovsky always had Auer in mind as the soloist for the premiere, and as the planned dedicatee.

We’re very lucky that a few bits of Auer’s playing survive on recording. Although he is remembered as the godfather of the great Russian school of violin playing, Auer himself was Hungarian and studied in Vienna with Jakob Dont, Josef Hellmesberger Sr. and Josef Joachim. As the excerpt above shows, what Auer got from Joachim was a kind of super-focused intensity of contact between bow and string, and a very sustained, well-projected, even, singing sound with fantastic clarity of articulation. Auer, at least in the few clips that survive, seems to play with a more frequent and intense vibrato than Joachim.

But what did his students get from Auer, and what, if anything, does their playing tell us about how the Tchaikovsky should be played? Perhaps no instrumental pedagogue in history had so huge a legacy of astounding students as Auer. Those who come close to him in sheer numbers like Ivan Galamian and Dorothy Delay in essence gave up playing to teach full time. Auer was a formidable and prolific performer and had a long career.

Auer’s greatest students, including Oscar Shumksy, Misha Elman, Jascha Heifitz, Efram Zimbalist and Nathan Milstein were a very diverse group of distinct personalities. No fan of the violin would ever mistake Heifitz’s playing for Elman’s. Their very different takes on the Tchaikovsky, however, share a number of qualities, most importantly, in my opinion, in their fundamental approach to the use of the bow. All of them are superb lyrical players, all play with incredible focus, and an incredible sense of linear intensity. Their “voices” were fundamentally different- Heifitz with his very fast vibrato and laser-like directness, Elman with his more old-school sensibility, his elegance and aristocratic passion, and Milstein with his incredible vocal naturalness and virtuoso’s sense of courting danger- for me, his was always the perfect voice, even if Heifitz was the more perfect singer. Vibrato in their performances is generously applied, but constantly varied and colored, and often quite restrained and narrow. Somewhere in their the breadth of their interpretive differences, the vastly wide-ranging contrasts of their personalities, and the similarity and variety of their tonal vocabularies, one begins to get a sense of what the parameters of a historically grounded approach to Tchaikovsky’s masterpiece might sound like, at least in instrumental terms. I’ve selected below, almost at random, recordings of three of these eminent violinists for comparison, but a curious listener will discover just as much of interest by seeing how each of these players’ approach varies throughout their career, from performance to performance, and recording to recording.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Je9L7UPwDF8

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HuF7EaV5EZo

Too many traditions?

If the careful study of early recordings can help us to understand the soloist’s balance of intensity, lyricism, power, delicacy and classical clarity that Tchaikovsky seemed to have in mind when writing the piece, it’s important to strenuously point out that I can scarcely think of any piece of music which has suffered more from being learned from recordings than this one. Far too many young violinists know only their own part (we call them “top liners”), and have bypassed careful study of the full score by substituting the imitation of other artists’ (and their own teachers’) mannerisms and choices.

In fact, the rigid regurgitation of the nuances of a given recording would surely have been abhorrent to a player like Mischa Elman, whose playing is marked by such a natural, easy, in-the-moment sense of flexibility, and an uncanny ability to make one wonder if he’s improvising at times.

Rubato is the salt and vibrato the pepper of Romantic music- the essential seasonings which brings the flavor of it to life. Tchaikovsky, for all his classicism, would probably be pretty horrified to hear a strictly metronomic “the Urtext and nothing but the Urtext” reading of his Concerto, but by the time one is listening to a third or fourth generation imitation of a tempo nuance that an early 20th c. player probably only did once or twice in his career, one has blurred completely the line between engaging creatively with Tchaikovsky’s text, and not knowing, or worse yet not caring, what that text actually is. Remember, you can learn a poem in a foreign language by ear and repeat it accurately without having any idea what it means- this is not an interpretive approach an artist ought to settle for.

My advice to a violinist learning, or relearning, the piece would be to learn it from the score and to analyze it as one would a symphonic work (ask a conductor or composer how if you need to), treating the solo part as an integrated and interdependent part of the musical whole. The first movement is symphonic in both scope and character, and it’s important for the soloist to not only have all kinds of cool ideas about when to take time and all that fun stuff, but to understand the structure, to understand how each section develops, ebbs and flows. How did Tchaikovsky hear the piece unfolding its totality in his inner ear?

The second movement’s lyrical simplicity and the finale’s rustic virtuosity show Tchaikovsky deploying very different facets of his art. For all its high spirits, the Finale is just as carefully (and beautifully) constructed as the first movement. It’s lighter character puts the concerto in the same tradition as concerti for violin and piano by Brahms and Beethoven, in which the main structural weight of the work is in the first movement. However, Tchaikovsky never intended the finale to be a throwaway affair, which is why the cuts (and the rewrites to the violin part) which originated with Auer are such a travesty. By shortening the movement, they turn it into something much more empty and merely showy than the composer intended. It’s no more repetitive than the last movement of the Beethoven Violin Concerto (less so, actually), and nobody would dare cut Beethoven.

Gimmicks are just gimmicks

It’s no surprise that a piece as popular and ubiquitous would invite performances which go to sometimes absurd lengths to stand out from the crowd. In 80’s and 90’s, the way to get noticed with the Tchaikovsky was to treat it like an Olympic sporting event and try to rack up as many world records as you could: the world’s widest vibrato, world’s closes-to-the-bridge contact point, world’s loudest violin, world’s fastest finale, world’s cleanest octaves… You get the picture. Even in concerts and recordings, the competition mentality seemed to dominate. As with the imitation of recordings, treating the work like a 100 yard dash or a powerlifting event tends to make one forget what the piece actually is- we play faster to show we can play faster, we play louder to show we can play louder.

More recently, we’ve seen a number of soloists chuck the baby right out with the bathwater of the competition mentality with performances that simply strive to be as bizarre and contrarian as possible. As anyone who has raised a toddler will know, being contrary does not always equate to being wise, reasonable, knowledgeable or inspired. Do we really need a ponticello Tchaikovsky, a Baroque Tchaikovksy, a flautando Tchaikovsky or or a fiddle Tchaikovsky? Or, for that matter, a brutalist Tchaikovsky or a metronome Tchaikovsky? All of these approaches can only be delivered by limiting the dynamic and expressive range of the violin, which seriously impairs the ability of the soloist to do justice to the structure of the work, particularly the first movement, with it’s long, gradually evolving melodic arches. A real re-think of the piece ought to be about a careful and detailed examination of the text, challenging oneself to find where the balance between head and heart lies. It’s about making millions of small decisions free from vanity, not about looking for one big blockbuster gimmick to get yourself noticed. It’s about finding 1000 ways to use and not vibrato, not simply turing it to stun or turning it off completely. Doing something novel with a piece like the Tchaikovsky is not hard- little kids come up with novel ideas for food all the time, but most folks wouldn’t want to eat roast beef with marshmallow sauce. Bringing such a familiar piece to life with total commitment and honesty is harder than simply playing the whole concerto with a bass bow. Moving an audience is harder, and far more meaningful, than simply surprising or shocking them.

At the end of the day, maybe the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto would actually benefit from a few more performances where the audience left talking more about Tchaikovsky’s genius and less about the approach of the soloist?

__________________________________

Post-script- Don’t forget to dance

Not long ago, I did the piece with my friend Tamsin Waley-Cohen, who recorded this fascinating little video with some of her thoughts about the piece. I think what she says about the stylistic commonalities between the Concerto and Tchaikovsky’s ballet scores is really spot on

A final thought about the cuts

I’ve conducted the Tchaikovsky now many times both with and without the cuts. In every case, I’ve found the cuts to be unnecessary and destructive, as are Auer’s re-writings of the solo part. However, that’s not say by any means that I haven’t enjoyed working with my colleagues in those performances. At the end of the day, it’s the violinist’s piece to make or break- the conductor can encourage, advise and suggest a little bit here and there, but at the end of the day, my job is to make their decision, whether I would have made the same decision, sound like the right decision. I’ve done some thrilling performances with the cuts, and one just hopes that someday, I can repeat the piece with those same wonderful colleagues without!

A Brodsky specialist speaks! The idea that the first performance went badly has been coloured a posthumous tendency to exclusively rely on Hanslick’s criticism. It overlooks the views of other critics who were present as evidenced by the Viennese press, as well as Anna Brodsky’s eye-witness account of the premiere. It was apparent that some had gone along specifically to engage in booing and catcalls, but that the performance went well. The consensus is that Brodsky played well and that even those who didn’t warm to the concerto conceded that it was a fine performance.

Brodsky himself was never proprieatorial about the piece even though he played it on numerous subsequent occasions and his markings in his copy are fascinating. His favourite concerto appears to have been the Bach A minor and later the Elgar.

What’s your take on the rather strange orchestral interlude in the first movement? I’m talking about the part after the big tutti, where the harmonies go into unusual territory. I find it one of the least satisfying passages in Tchaikovsky’s output and I think few conductors try to make sense of it. I’d be happy for the cut that excludes these measures to become canonic.