The rediscovery and reevaluation of the music of Mieczyslaw Weinberg is surely one of the more positive stories in classical music in recent years. If this blog post piques your interest in Weinberg, do check out the podcast version of BBC Radio 3’s recent “Composer of the Week” series on him (scroll down the page and click where it says “clip”). Donald Macleod’s description of Weinberg as “the best composer you’ve probably never heard of” is telling. There are now recordings available of most of his orchestral music and more comes out all the time. A major biography is urgently needed. Sadly the only substantial English-language book on Weinberg is a strangely disinterested and low-energy affair; hardly more than a list of dates, places and works, with fairly little to offer in terms of insightful commentary about, or even perceptible enthusiasm for, the music. It does, at least, cover the biographical basics in a utilitarian way, and is worth reading on that basis. His String Trio is a remarkable work that seems to always have an incredible impact whenever we play it live. My program note for the Trio follows.

The rediscovery and reevaluation of the music of Mieczyslaw Weinberg is surely one of the more positive stories in classical music in recent years. If this blog post piques your interest in Weinberg, do check out the podcast version of BBC Radio 3’s recent “Composer of the Week” series on him (scroll down the page and click where it says “clip”). Donald Macleod’s description of Weinberg as “the best composer you’ve probably never heard of” is telling. There are now recordings available of most of his orchestral music and more comes out all the time. A major biography is urgently needed. Sadly the only substantial English-language book on Weinberg is a strangely disinterested and low-energy affair; hardly more than a list of dates, places and works, with fairly little to offer in terms of insightful commentary about, or even perceptible enthusiasm for, the music. It does, at least, cover the biographical basics in a utilitarian way, and is worth reading on that basis. His String Trio is a remarkable work that seems to always have an incredible impact whenever we play it live. My program note for the Trio follows.

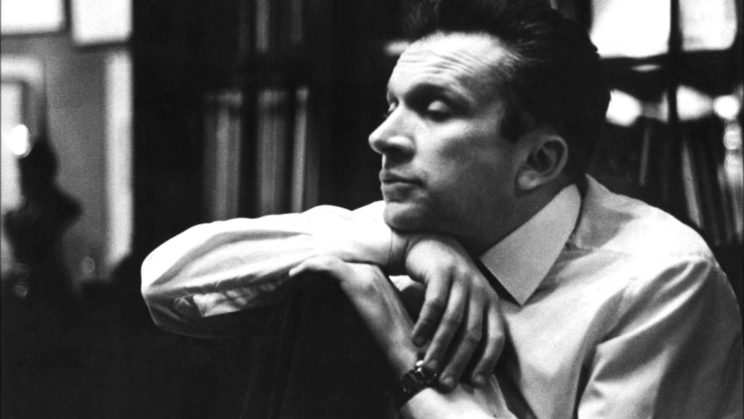

Mieczyslaw Weinberg was born in Warsaw in 1919, where he completed his studies as a pianist at the Conservatory in 1939. He had hardly finished his education when he had to flee the German occupation of Warsaw. He managed to escape to the Russian border, but his parents and sister were captured and burned alive. During 1942, Weinberg was a refugee in Tashkent when the composer Israel Finkelstein, a colleague of Shostakovich, took an interest in him. Finkelstein showed Shostakovich Weinberg’s First Symphony, and Shostakovich was so impressed that he arranged for Weinberg to move to Moscow. The two composers forged a close friendship that remained central to both of their lives until Shostakovich’s death in 1975. Weinberg never forgot the role Shostakovich had played in saving his life and was clearly grateful for the inspiration he had taken from him, writing ‘although I never had lessons from him, I count myself as his pupil, as his flesh and blood’. In exchange, Weinberg fostered Shostakovich’s abiding interest in Jewish folk music, and it is around the time of their emerging friendship that Shostakovich wrote his most important Jewish-themed works: the Second Piano Trio, the Fourth String Quartet and the song-cycle ‘From Jewish Poetry’.

The influence of Jewish, gypsy and Moldavian folks themes is pervasive in Weinberg’s String Trio (1950). With his ability to seamlessly integrate folk material, fugal technique and post-tonal harmony, Weinberg in 1950 seems already quite far along in reconciling the old and new, as Penderecki, Kurtág and Schnittke would seek to do a half-generation later. The first movement opens with a gently melancholic tune in the cello and builds to a furious climax, before winding down in a more Klezmer-inflected restatement of the opening. The haunting second movement, an eerie fugue, is the one part of the Trio that is free of folk influence. The finale, on the other hand, is almost pure folk music: emerging over a long, slow-burning ostinato, it builds to a screaming climax of orchestral proportions, before dying away and ending in desolation. It is not known if the work was premiered publicly at the time it was written (it seems unlikely) – it remained unpublished until 2007. Shortly after completing the piece, Weinberg was arrested by the KGB for ‘Zionist activities’ and was only released when Shostakovich interceded on his behalf. When the authorities let him out of prison a few days after Stalin’s death in March 1953, it was Shostakovich he rang first.

c. 2012 Kenneth Woods

Which book on Weinberg is the reviewer referring to? He seems unaware of “Mieczyslaw Weinberg; In Search of Freedom” The excellent biography by Professor David Fanning, which was published in 2009, when the revival and rehabilitation of Weinberg was still in its early stages. He has researched Weinberg’s life, works and legacy with passion and empathy. The only reservation I would make is that I would like to see more musical examples but maybe there was a problem accessing these.