Ken will be conducting Vaughan Williams Fifth Symphony with the English Symphony Orchestra at the 2019 Elgar Festival in Worcester Cathedral on Saturday the 1st of June, 2019.

Details here.

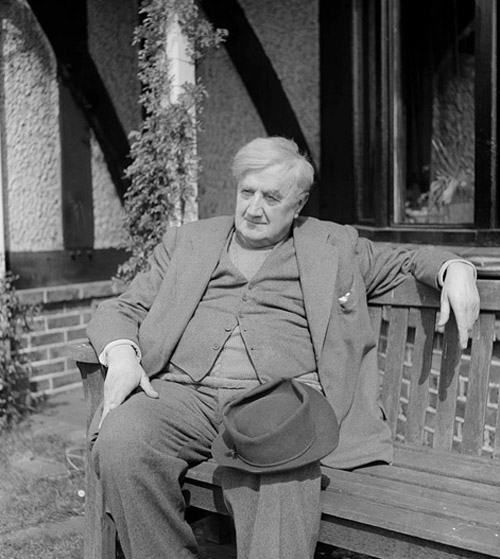

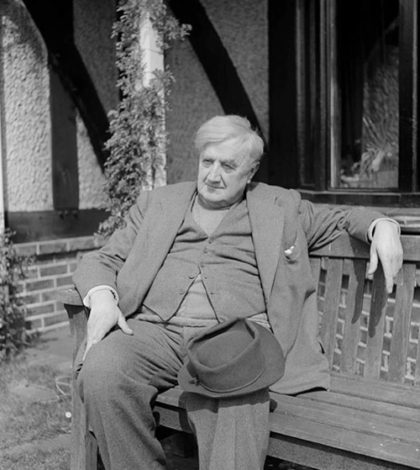

In 1952, when Vaughan Williams was asked to pick one of his symphonies for a special concert celebrating his 80th birthday, he chose the Fifth Symphony. That this work would hold a special place in its creator’s heart should not surprise us. No other work of his had such a long and complex gestation with such profound connections to his earlier works, nor is there any work which so perfectly captures his most personal and distinctive of musical languages. I vividly remember our former composer-in-association John McCabe telling me that he held RVW to be “the greatest 20th Century symphonist, bar none.” At first, I was stunned by John’s suggestion – what about Mahler, Shostakovich, Nielsen and even our own Edward Elgar? But if one is looking to make John’s case for RVW’s symphonic supremacy, the Fifth Symphony is surely the place to start.

Vaughan Williams began sketching the Fifth Symphony in 1936, and by 1938 was fully engrossed in the score. Progress on the Fifth was slowed by numerous external factors. Vaughan Williams, who had served as a medical orderly in World War I soon became involved in the efforts of the new World War, and also had to meet deadlines for several film scores and shorter pieces, including the Serenade to Music and Five Variants of ‘Dives and Lazarus. He finally completed the symphony in early 1943 and revised it in 1952. The work is dedicated “Without permission and with the sincerest of flattery to Jean Sibelius, whose great example is worthy of imitation.” It was premiered under the composer’s baton by the London Philharmonic at the 1943 Proms.

Although the Fifth Symphony was begun in 1936, the work has significant thematic connections with his opera, or ‘morality’ as he often called it, Pilgrim’s Progress, which he worked on from 1909-1952. The dedication to Sibelius serves as a worthy signal of the work’s seriousness of purpose. Musicologist Michael Steinberg writes that for Vaughan Williams, as for Sibelius, “the symphony was the form in which a composer might express his deepest, most complex, most personal feelings and realise his richest and most evolved compositional plans.”

The work is outwardly abstract, but the many references to Pilgrim’s Progress, other works from his catalogue and his biographical circumstances paint a picture of a multi-layered work from a composer who was both uplifted by newly found love and in despair at the return of war.

An early version of the first movement of the symphony was called Funeral March for the Old Order, but the mood is perhaps more gently melancholy than militaristic. It’s certainly about as far as you can get from the many funeral marches which populate the symphonies of Gustav Mahler (whose music he loathed). Like much of his music, Vaughan Williams finds emotional texture in the ambiguities of modal harmony. The symphony opens with a gently rocking horn fanfare in D major, but the horns’ bittersweet but hopeful melody is somewhat undermined by C natural in the low strings which underpins the opening. That C turns the music in a dark direction, moving it through C minor before there bursts forth an aspiring violin melody in E major. This is a quote from the “Alleluia” Vaughan Williams wrote in 1906 for The English Hymnal, a fragment he had already quoted in several other works.

The Scherzo is both shadowy and virtuosic, dark and wickedly playful. Vaughan Williams called his early sketch of it Exit of the Ghosts of the Past, and ghostly it is. It is followed by what must be one of the most touching symphonic slow movements of the last 100 years, the Romanza. Some commentators have read the title of the movement as a reference to his new-found love and future wife, Ursula, but it is also in this movement that the connections to Pilgrim’s Progress are most telling. He wrote a passage taken from Bunyan’s novel into his manuscript at the top of the Romanza: “Upon this place stood a cross, and a little below a sepulcher. Then he said: ‘He hath given me rest by his sorrow, and life by his death.’” In the opera, those words are given to the same poignant melody the english horn plays to launch this movement. Later, there is an anguished passage in a faster tempo which, in RVW’s Pilgrim’s Progress, is associated with the Pilgrim’s words “Save me, Lord, my burden is greater than I can bear.”

The Finale is a passacaglia worthy of consideration in the same breath as that other great symphonic passacaglia which ends Brahms Fourth Symphony. Where Brahms’ uses the passacaglia’s repeating structure to create a sense of driving headlong into unavoidable catastrophe, Vaughan Williams turns the passacaglia into something like a rite of purification. Gradually, he strips away the modal colourations which have given the symphony so much of its character, moving toward pure, almost Bach-ian D Major. The horn calls which opened the symphony now return in blazing fortissimo and one more “Allelulia” sounds from the hymn All Creatures of Our God and King. Michael Steinberg describes the ending better than I can: “In peaceful meditation… the music arrives at its destination: a luminous D major close, hushed, beatific, with an ineffable sense of peace. Here, if anywhere in music, is transcendence.”

Thanks for the nice exploration of the fifth— It was my introduction to Vaughan Williams– I still have the Barbirolli LP with the Turner painting on the cover from well over 50 years ago. Perhaps you’ll record it one day.

Beautiful write up. I love this piece desperately.

I had the great honor of being a guest of Ursula’s many years ago. It was astonishing to hear her describe the premiere of this work, my favorite of all of Vaughan Williams’ symphonies. Thank you for your sensitive discussion.

There is a percussive sound in the first few minutes of the 5th Symphony that I would like to identify. It has more distinctive pitch than an ordinary percussive instrument like the tympany. I wonder if it could be a cellist or bass violist percussing the strings of his instrument with his bow. I’ve particularly enjoyed the Frankfort Radio Symphony performance, conducted in this instance by Sir Andrew Davis. Usually, the cameramen are skillful at showing which performer is making distinctive sounds, but it didn’t happen in this case.

Thank you very much.

This is one of my favorite symphonies but the fourth movement often literally leaves me in tears. I really enjoyed your write up and explanation. Others I’ve found on the web lose the joy in all the details. Thank you for this. I’ll be copying and keeping this for future reference and enjoyment.