Gunnar Johansen was a legendary figure in my home town of Madison, Wisconsin. He retired from the University of Wisconsin in 1976, when I would have been seven, so he was practically the stuff of legend throughout most of my youth (we never met). He died in 1991, during the years when I returned to Madison to get my Masters degree in cello with Parry Karp. I learned of his death when I opened the New York Times (exclusively an actual newsPAPER in those days) and saw his obituary. I was pretty damn impressed that someone from Madison was in the Times. Often, when a great composer or musician dies, there is a period of time during which they seem to fall out of fashion and into obscurity for a couple of decades, in spite of the tireless efforts by those who were close to them to keep the flame of their memory burning. In Gunnar’s case, it has been James P. Colias, Gunnar’s friend, former student and Trustee of the Gunnar and Lorraine Johansen Charitable Trust, who has worked for thirty years to protect, preserve and promote Gunnar’s legacy. Nonetheless, many of us don’t know enough about this unique figure.

Gunnar Johansen was a legendary figure in my home town of Madison, Wisconsin. He retired from the University of Wisconsin in 1976, when I would have been seven, so he was practically the stuff of legend throughout most of my youth (we never met). He died in 1991, during the years when I returned to Madison to get my Masters degree in cello with Parry Karp. I learned of his death when I opened the New York Times (exclusively an actual newsPAPER in those days) and saw his obituary. I was pretty damn impressed that someone from Madison was in the Times. Often, when a great composer or musician dies, there is a period of time during which they seem to fall out of fashion and into obscurity for a couple of decades, in spite of the tireless efforts by those who were close to them to keep the flame of their memory burning. In Gunnar’s case, it has been James P. Colias, Gunnar’s friend, former student and Trustee of the Gunnar and Lorraine Johansen Charitable Trust, who has worked for thirty years to protect, preserve and promote Gunnar’s legacy. Nonetheless, many of us don’t know enough about this unique figure.

So, who was Gunnar Johansen, and why have I called him ‘the first Millennial”?

The Early Years

Gunnar was born in 1906 in Denmark. Musically gifted, the piano would quickly become the center point of a wide circle of interests and passions, including composition, teaching and technology. As a young Danish pianist, he grew up alongside Victor Borge, with whom he remained lifelong friends.

Johansen’s most important teacher was Egon Petri, with whom Borge also studied, a leading pupil of Ferruccio Busoni. Other important Petri students would include Earl Wild, Eugene Istomin and John Ogden. Petri considered himself more a disciple than a student of Busoni. Following his example, Petri focused on the works of Johann Sebastian Bach and Franz Liszt, who, along with music by Busoni himself, were at the centre of his repertoire. These composers were also to be central to Johansen’s repertoire and life’s work as we shall see.

Johansen, a handsome chap and always a charismatic figure, seemed poised for a major career as a touring virtuoso soloist. Instead, he became something more original, important and interesting.

Following his studies with Petri, Johansen moved to San Francisco. He loved the West Coast vibe, and eventually bought a large property in the California wilderness .

“The first professional musician to settle on the South Coast was Gunnar Johansen. In love with ideas, airplanes, Romantic music, his motorcycle and pretty girls, this handsome Dane moved to California in 1929 with his young American wife. There he soon became known for his weekly radio broadcasts and the artistry he displayed in his many concerts -and his enthusiastic sociability.” Lucie Marshall

It was in San Francisco that his career took a fateful turn. Johansen was engaged by the local NBC radio station to give weekly on-air recitals. Johansen, who already had a huge repertoire, relished the challenge of playing a new programme every week, and quickly realised there was a huge potential in radio to engage, enlighten and even educate audiences. He also became an active concerto soloist, appearing with the San Francisco Symphony under Pierre Monteux and Bruno Walter. In 1934 he appeared with Frederick Stock and the Chicago Symphony as the second pianist (the first had been the composer) to perform then-nearly brand-new (1926) Fourth Piano Concerto of Rachmaninoff, and at the performance the audience demanded he encore the entire last movement.

The Artist-in-Residence

As a natural outgrowth of his NBC recital series, Johansen developed a series of twelve “historical recitals,” intended to be performed over a month. These were meant to embrace “the whole range of keyboard music from the early Renaissance to the twentieth century.” The massive project was presented in San Francisco, Chicago, New York, Stockholm, Berkeley, at William Woods College in Fulton, Missouri, and Cornell. Eventually, he brought the series to my home town, Madison, Wisconsin in 1939. His series made such an impact on the community at the University of Wisconsin that they invited him to become an “Artist-in-Residence”. Johansen was thus the first musician appointed as an Artist-in-Residence at an American university. Residencies like his now exist all over the USA and the world, bringing world-class musicians and teachers to campuses and communities of all sizes in all locations. Residencies have become one of the indispensable underpinnings of cultural life, and it all started with Johansen in Madison.

While the specifics of a residency vary depending on the nature and needs of the community, the basic template remains the same as when I did my first run as an Artist-in-Residence for the National Endowment for the Arts in the early 1990’s, and when Johansen invented the job in 1939. You combine a series of concerts intended to build awareness of, and enthusiasm for, the music you love, with a mix of teaching and outreach. Most importantly, it gives the artist a practical framework in which to develop their creative output – through the residency they have time to rehearse, practice, compose, write or publish, and the community, in exchange, gets access to high quality performances.

Johansen, with his background at NBC, quickly realised that if he wanted to really reach the wider community, playing cozy recitals for the faculty at Music Hall wouldn’t suffice. He had to embrace modern technology.

Many Wisconsinites will proudly tell you that WHA is the oldest public (as opposed to commercial) radio station in the country. I couldn’t find any evidence to support, or challenge, that assertion in over five minutes of research this morning, so we shall accept that as fact for purposes of this essay. Then, as now, public radio struggled with funding. One way in which they were able to keep the station running was to use it as a supplemental source of courses during the Great Depression, much in the same way we depend on ‘online learning’ during the Covid pandemic. Johansen moved his concerts to the WHA studios and in the 1940’s, Johansen performed ambitious series of recitals and live radio broadcasts, including the complete chamber music of Beethoven and Brahms with the Pro Arte Quartet (who joined Johansen in Madison as the first-ever quartet-in-residence at a university. I would later study with their longest serving member, Parry Karp. The news that they would be coming to Madison was key in securing Johansen’s commitment to come); the complete piano/keyboard literature of Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert, Chopin and Bach; as well as a series on the evolution of the piano sonata. Although the technology was still very much analogue, Johansen had created the first ‘online’ residency in 1939.

A priceless link to a great tradition – Johansen plays Busoni, his idol and the teacher of Gunnar’s teacher and mentor, Egon Petri

As part of his busy life on campus, Johansen made his teaching as outward facing as possible. Where most musicians prefer the cozy atmosphere of their private studio, Johansen taught a weekly course called “Music in Performance”, open to the entire campus. The class attracted sessions of 750 students at a time, making Johansen something like a college-town Leonard Bernstein as animateur and guide to the world of music.

How one pianist could keep up with such an onslaught of repertoire boggles the mind. Most soloists today actually keep to a carefully chosen repertoire. They might offer four or five concertos at a time and one or two recital programs, which they then repeat and repeat in different cities. Same program, new city, repeat. Johansen played just as often, but always a different program in the same city, and almost always with the red light on. How did he maintain the pace?

The Record Label

As it turned out, it was the radio station which couldn’t keep up with Gunnar. Always fascinated with technology, he got the technicians to show him how the tape machines worked in the studio. Eventually he borrowed one of the machines to take to his home in Blue Mounds so he could record there. This was in 1950. He was drawing to the end of his live cycle of the complete works of Bach and was about to perform the Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor. At that time, he had a double keyboard piano at his home (see below for more about this fascinating instrument), so he had the idea to borrow some equipment so he could record using that piano. The resulting record would become “Album I” in his series of the complete keyboard music of Bach. Once set up in Blue Mounds, he decided to stay, and the University later bought him state of the art equipment to support his work there.

Having invented the artist-in-residence concept and the online residency, Johansen would now develop the idea of an artist-owned and -led record company he called Artist Direct (all this over forty years before David Finckel and Wu Han started their own ArtistLed records with much the same ethos). Instead of his work reaching the whole state of Wisconsin, by releasing his recordings on LPs, he could, in theory, reach listeners worldwide. Although his first recordings were using his piano in his living room, one might well call him the first “bedroom musician.” In time, he had a beautiful studio built as an addition to his Blue Mounds home, designed by one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s most prominent disciples, Herbert Fritz Jr. Eventually, his instruments there would include three grand pianos, Baroque instruments like the clavichord and harpsichord, and a square piano. There he worked tirelessly, performing, engineering and releasing his own albums on LP and later cassette. The setup impressed many notable colleagues, including André Segovia who visited and said “Oh, I so wish I had a place like this! I sit there in the professional recording studios, play a work perfectly … and then they tell me, ‘We heard your chair creak at one point,” or” your shoe hit the floor” … and we have to do it over again!'”

He even wrote his own program notes. Just think of what he could have done with Bandcamp and YouTube.

At over 120 minutes, this is but a tiny taste of Johansen’s fifty-three albums dedicated to the music of Liszt

In typical Johansen fashion, his recording projects were educational, not promotional in nature. Rather than release recital programmes showcasing his range and promoting his performing career, he focused his recording energies on a survey of the complete works of one composer at a time. Always one to think big, he started with the first complete recording of the keyboard music of Bach on forty-three LPs and cassettes. Liszt posed an even more enormous challenge, with Johansen’s survey of all Liszt’s piano music then available, occupying fifty-one albums (all of Liszt’s then-available original works, but not all of the transcriptions). In addition to these two monumental undertakings, he also recorded The Piano Music of Ferruccio Busoni, his grand-teacher, on seven records and cassettes, The Keyboard Works of Gunnar Johansen on twenty albums his Historical Recital Series programs from the 1930’s on 12 albums, and The Piano Music of Ignaz Friedman on seven albums. Johansen, to his credit, seems to have been one of the first classical artists to see the limitations of the commercial record label system and, more importantly, to put into practice a viable alternative . By creating his own model, he was able to build a body of work quite unique in recorded history. As the recording industry crumbled in the 1990’s and 2000’s, thousands and thousands of artists, from the most well-known to the completely unknown, unwittingly turned to Johansen’s model, developing and distributing their own projects.

The Secret Weapon

For his Bach series, Johansen was aided by something of a ‘secret weapon,’ a piano with two keyboards, officially called the “Duplex-Coupler Grand Pianoforte.” The dual-keyboard concept was developed in the early 20th C. by the Hungarian pianist and composer Emánuel Moór. Moór’s design meant that a piano with one set of hammers, strings and dampers could be controlled by two keyboards, staggered an octave apart. The keys could also be mechanically linked, which allowed the player to play an octave with one finger.

Johansen’s recording of JS Bach’s Goldberg Variations played on his double keyboard Bösendorfer, and recorded in his home studio in Blue Mounds.

It was during a visit to New York City in 1947 that philanthropist Anna Clark offered Gunnar the Bösendorfer/Moór piano which would play such an important role in his recordings. The story of the Clark family alone, like so many people attached to Johansen’s life, is the stuff of movies. Anna Clark was the second wife of William A. Clark, copper baron, founder of Las Vegas, disgraced US Senator, and scoundrel par excellence. Both Clark County, Nevada and Clarksdale, Arizona were named for him, which probably is all the proof one needs that nice guys finish last. Wikipedia says of Mr. Clark that:

Clark yearned to be a statesman and used his newspaper, the Butte Miner, to push his political ambitions. At this time, Butte was one of the largest cities in the West. He became a hero in Helena, Montana, by campaigning for its selection as the state capital instead of Anaconda. This battle for the placement of the capital had subtle Irish vs. English, Catholic vs. Protestant, and non-Masonic vs. Masonic elements. Clark’s long-standing dream of becoming a United States Senator resulted in scandal in 1899 when it was revealed that he bribed members of the Montana State Legislature in return for their votes. At the time, U.S. Senators were chosen by their respective state legislatures. The corruption of his election contributed to the passage of the 17th Amendment. The U.S. Senate refused to seat Clark because of the 1899 bribery scheme, but a later senate campaign was successful, and he served a single term from 1901 until 1907. In responding to criticism of his bribery of the Montana legislature, Clark is reported to have said, “I never bought a man who wasn’t for sale.” Clark died at the age of 86 in his New York City mansion. His estate at his death was estimated to be worth $300 million, (equivalent to $4,373,624,000 in today’s dollars), making him one of the wealthiest Americans ever.

In a 1907 essay, Mark Twain, who was a close friend of Clark’s rival Henry H. Rogers, an organizer of the Amalgamated Copper Mining Company, portrayed Clark as the very embodiment of Gilded Age excess and corruption:

He is as rotten a human being as can be found anywhere under the flag; he is a shame to the American nation, and no one has helped to send him to the Senate who did not know that his proper place was the penitentiary, with a ball and chain on his legs. To my mind he is the most disgusting creature that the republic has produced since Tweed’s time.

One can’t help but be reminded of a more recent wealthy politician whose Twain’s words (“the most disgusting creature that the republic has produced”) would aptly describe. And there is this about Clark, which could have been written recently:

“Once in office, Clark was motivated less by a wish to serve his constituents than by his desire to improve the efficiency and profitability of his various businesses.” From PBS.org’s American Experience [sound familiar?]

To be fair, Clark may have been a disgusting creature and a scoundrel, but his son, William Andrews Clark Jr.founded the Los Angeles Philharmonic, which debuted in the Trinity Auditorium in 1919, and he bequeathed his library of rare books and manuscripts, the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, to the University of California, Los Angeles upon his death in 1934. He also helped to fund the construction of the Hollywood Bowl. Today’s “Disgusting Creature” Jr probably won’t leave such a positive legacy. Sometimes it is better if the apple falls further from the tree, as it seemed to in this case.

William Andrews Clark Jr. was the most devoted maker of beauty of all the men I have ever anywhere known. . . . One day he found himself with a rare and priceless library and no safe place to put it; he thereupon called in Mr. Robert D. Farquhar and instructed him to build a jewel box for the protection of his treasures . . . . And Mr. Farquhar did as he was told with a result that will fill you with astonishment if you will visit the Library. —Ernest Carroll Moore, Provost and Vice-President of UCLA

But I digress. A lot.

Anna Clark, a Paris-trained harpist and patron to many musicians, had bought the Bösendorfer/Moór in the 1930’s. This is a remarkable and historic instrument. It was quite possible the last Moór piano made (he died in 1931). Of the sixty-one Moór’s built, only 12 survive and only six are playable (two of which were, of course, associated with Johansen). This Clark/Johansen piano is the only one of its kind to have come on sale in ages – it is currently being sold by the Gunnar and Lorraine Charitable Trust (email for more information). Proceeds will support the preservation of Johansen’s musical legacy.

Johansen taught Anna’s step-granddaughter, Agnes Albert (it appears that Agnes and Anna referred to each other as aunt and niece rather than step-grandmother and step-granddaughter). Mrs. Albert was a board member (she served from 1952 until her death in 2002 at the age of 94) and supporter of the San Francisco Symphony (which her uncle, Richard Tubin, co-founded in 1911). She was also an accomplished pianist and appeared twice as a soloist with the SFSO in Franck’s Symphonic Variations in 1932 and 1952. James Colias describes how Johansen met Anna Clark through Mrs. Albert and came to be offered the piano:

“On the advice of Agnes, Anna Clark engaged Gunnar to play a concert in her grand Fifth Avenue apartment (of some 52 rooms) and paid him a good fee. After the performance, she said, “Oh … by the way …down that hallway in one of the rooms is a special piano. Perhaps you’d like to see it.” He did, and told her he found it remarkable. Anna said, “Would you like it?” Gunnar accepted. “

Only about sixty-five Moór pianos were made – most of them by Bösendorfer. Steinway in Hamburg made only one such instrument, for the industrialist Werner von Siemens, which was kept in the private concert hall (reputed to seat between 450-600 people) in his home. The Steinway/Moór had been very heavily damaged in the bombing of the von Siemens estate during the War, and it wasn’t until the 1950’s that a full repair and restoration was begun. This was a huge challenge in part because all of the design plans for the one-of-a-kind instrument had been destroyed in the war (the challenge of re-building the piano without specs and designs was again faced by Steinway in 2006 when they performed the most recent restoration in New York, see the video below for more details). Once the Steinway was ready, the company thought about which ‘Steinway Artist” pianist it might suit. They knew of Johansen’s use of the Bösendorfer/Moór in Blue Mounds, and so they approached him. Gunnar was thrilled to learn of the instrument, but it took him six years to secure funding (eventually provided by Madison-area music lovers Harry and Evelyn Steenbock) to purchase the instrument through the UW for his use. Steinway’s patience in waiting six years to sell such a unique instrument is a huge credit to the character of the company at that time, as well as a resounding endorsement of their esteem for Johansen. The Steinway remained at Johansen’s home in Blue Mounds until the death of his wife Lorraine in 2004, after which it was moved to the UW campus, where current Artist-in-Residence Chris Taylor came across the Steinway and began using it in his own Goldberg performances following a rebuild.

Johansen’s successor at the University of Wisconsin, Christopher Taylor, gives a tour of Johansen’s Steinway/Moór piano

The Legend

One of the most well-known tales of Johansen’s exploits involves the Beethoven Violin Concerto. While the review and news coverage of the event as reported in the New York Times remains available in their archive, many specifics of the account there are inaccurate. Peter Serkin had been scheduled to perform Beethoven’s own arrangement of the Violin Concerto with the Philadelphia Orchestra and Eugene Ormandy in New York’s Philharmonic Hall (now Geffen Hall) in 1969. This performance was to be the US premiere of the piano version of the Beethoven Violin Concerto. Serkin and Ormandy fell out during rehearsals over the question of tempi. Ormandy felt that Serkin’s slow tempi were suitable for a violin, but not on the piano. Having reached an artistic impasse, it was announced that Peter Serkin was “indisposed.” With only a day until the concert, calls went out to all the major pianists in New York, but no pianist then working in the US had the Violin Concerto in their repertoire. The eleventh pianist the orchestra called was Peter’s father, Rudolf Serkin. It was he who said the only pianist he could imagine doing the work on such short notice was Johansen.”I’d never take that chance,” Rudolf Serkin said to Boris Sokolov, then the manager of the Philadelphia Orchestra. “The only pianist who would be willing to take on that risk is Gunnar Johansen.”

Johansen received the call from Sokolov, that Monday afternoon while teaching James Colias, now Trustee of the Johansen Trust. Gunnar didn’t know the piano version, so together they went to the basement of Music Hall to find it. There, in the library, Johansen flipped through the piece and said to Colias “Yes, I believe I can handle this.” He returned to his studio and told Sokolov he was on the way. That done, he raced home to Blue Mounds, collected his tails and some basic supplies, then went straight to the airport (this proved to be a wasted trip, as the dry-cleaners in New York later misplaced his jacket, so he had to play the concert in his regular suit). He spent the flight studying the score silently, but when he arrived in New York, he learned that in all the chaos the orchestra had failed to book a hotel for him. Hours went by as he went from packed hotel to packed hotel before he finally found a place after midnight.

The next morning, Johansen went to Steinway Hall. There, on the morning of the concert, he was finally able to sit at a piano and play the solo part for the first time. After lunch, he joined the orchestra for the rehearsal. Ormandy announced that they would play the concerto first without cadenzas, and that he, Johansen and the timpanist would stay back after rehearsal to rehearse the cadenza which Beethoven had written for the piano version. Johansen was surprised – he told Ormandy (in the rehearsal) that the edition he’d found in the UW library had no cadenzas, so he had planned simply to improvise them. But no artist of Johansen’s calibre could knowingly forsake playing Beethoven’s own first movement cadenza, so Johansen assured Ormandy and the orchestra that he would play the Beethoven cadenza if they could find a copy for him. Ormandy was so staggered by Johansen’s offer that he said to entire orchestra (then all male) “Why aren’t you gentlemen on your knees praying?!” Ormandy had planned to explain the entire situation to the audience, but Johansen was so in command in rehearsal that Ormandy decided “no apologies were necessary” and that Gunnar’s playing should be allowed to speak for itself. It may have been just as well. In his review, Harold Schonberg said that had the audience known what Johansen had just achieved they might well have torn the building down in their enthusiasm. Schonberg (the man who, after all, wrote the book on the great pianists) called the ensuing performance “a complete tour-de-force, and ‘miracle’ is not too strong a word.” Schonberg noted that “not a note was misplaced, the entrances were secure, there was never a hint of hesitancy or awkwardness.” At 62 years of age, this unknown musician from Blue Mounds, Wisconsin was suddenly the most talked about pianist in the USA.

The Composer

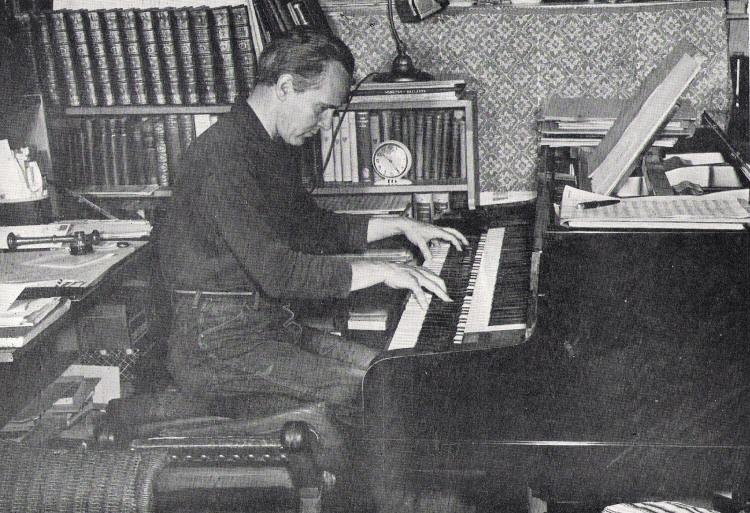

Gunnar Johansen at his composition desk

Johansen’s pianistic exploits would surely have been more than enough to occupy most people for a lifetime, but he was also a prolific composer. Several years, his name came up on Twitter in a discussion of ‘forgotten’ great pianists and I mentioned he was from my neck of the woods. Someone then commented that he was a composer – something I hadn’t known till then. A bit of internet research showed me that he was quite a composer. He wrote 31 piano sonatas, taking care to stop one short of Beethoven’s total, three piano concertos, a set of orchestral variations and quite a bit of chamber music. For a figure I’ve nicknamed “The First Millennial”, his profile as a composer would seem to put him squarely in the great tradition of pianist-composers from Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert and Schumann through to Brahms and his idol, Busoni.

In the tradition of the great pianist-composers, Johansen discusses and performs his Piano Sonata No. 2, which he called the “Pearl Harbor”

To a large extent, that’s true, there is another fascinating aspect to his compositional output. Having forsworn any more piano sonatas after his 31st, Johansen invented a new genre he called “improvised sonatas” which he recorded direct to tape in his home studio. There are over 500 of these.

Gunnar discusses and performs his Improvised Sonata No. 108

The Improvised Sonatas seemed to emerge out of Johansen’s reading of The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci in 1952, particularly this phrase: “Music has two ills, the one mortal, the other wasting: the mortal is ever allied with the instant which follows that of the music’s utterance, the wasting lies in its repetition, making it seem contemptible and mean.”

Composer, pianist and author Gordon Rumson (whose essay on Johansen has been invaluable in preparing this) says that, having first read these words, “The effect [on Johansen] was immediate and life-changing.” Inspired by da Vinci, he recorded his first Improvised Sonata (numbered 32), on January 14, 1953, and his last, number 550 on July 13 1990. Rumson writes of this project that:

Most of Johansen’s energies were poured into these spontaneous creations that attempted to capture the moment of inspiration. The results are not jazz, though there are some works in that genre, rather Johansen’s improvisational method continued the interrupted lineage of Mozart, Beethoven and Liszt that viewed spontaneous creation as fully the equal of reflective effort. The closest examples in modern practice to Johansen’s work are the public concerts of Keith Jarrett. It is unlikely that Jarrett is aware of Johansen, but the connection is clear.

Since re-discovering Johansen’s work in 2013, I’ve been working with the indomitable James Colias, Johansen’s great friend, assistant and Trustee of the Gunnar and Lorraine Johansen Charitable Trust, to try to develop a recording of his orchestral music. (James was also Victor Borge’s Personal Manager for 25 years – a connection made via Johansen’s and Borge’s friendship). It’s a huge project as there are no usable performing materials, and the manuscripts are not in great shape. There are concerns that one of the three piano concertos may be lost. The Third Concerto is a tour-de-force, and there is an archival recording of the premiere with the Madison Symphony made in the early 1980’s. While the recording quality and balance is not ideal, and the performance is clearly that of a well-prepared regional orchestra rather than an ensemble of international standard, the impression is of a first-class work. Both Paul Badura-Skoda and James Tocco have written in support of the piece in the past. Given that I didn’t even know of Johansen’s compositions as a professional musician who grew up just 20 minutes from the house in which he wrote them, the need for a new series of recordings celebrating the legacy of this most-recorded of pianists is obvious. If only funders and sponsors saw it that way!

The Academy

Johansen’s encounter with Da Vinci had another profound affect on his life. Again, to quote Rumson:

Johansen came to believe that the fragmentation of human knowledge into many specializations prevented us from solving our most pressing problems. To address this crisis in human thought, Johansen established the Leonardo Academy (after the painter and renaissance man, Leonardo da Vinci) devoted to the fruitful integration of the arts and sciences. Conferences included such distinguished participants as Edward Teller, inventor of the American hydrogen bomb, and Buckminster Fuller, inventor of the geodesic dome.

So, did Johansen also invent the think tank? Or the Aspen Institute? That’s probably over-egging the pudding, but certainly, he was well ahead of his time in seeing the need for musicians to engage more deeply with shaping the societies in which they live. And he was particularly visionary in identifying the threat that the ‘fragmentation of human knowledge” posed to the future of humanity.

The Challenge

How is it, then, that such a protean, unique, important and prolific figure is almost completely unknown today? As a pioneer of so many of the key aspects of today’s musical and cultural life, surely he is someone children should learn about in school? Not someone a professional musician who grew up 20 minutes away from him rediscovers by accident on Twitter?

Sadly, most of Johansen’s recorded legacy is out of print – although all his recordings and music remain available via the Trust. Thousands of copies of the old LPs and cassettes were still at the Johansen Archives when I visited in 2013, but the costs of storing them, and the relatively fragile nature of the cassettes, has meant that at some point, most of that stock will have to be recycled. This is tragic. It is also a source of great regret that Johansen was persuaded to switch to cassettes, with their low quality and tendency to degrade and warble.

Digitizing such an enormous body of work is a complex and time-consuming task, which requires both musical and technical expertise. There are also ethical questions about how best to do this. Working as a one-man operation empowered Johansen to produce his titanic output, but he was not a trained audio engineer, and neither living room nor his studio were possessed of an acoustic like that of Carnegie Hall. The basic sound on these recordings is very boxy and dry, in spite of the fact that he had some fantastic recording equipment supplied by the University of Wisconsin, including a collection of Neumann microphones. There are also many instances of distortion on the LPs – whether these are also on the master tapes is unknown, but I understand the masters have survived and have been digitized, but not yet restored or remastered, by the Trust.

With today’s technology, I can record myself at home and place my performance in a near-perfect recreation of the Concertgebouw or the Musikverien at the touch of a button. But is it ethical to tamper with the sound of a recording made by an artist of Johansen’s stature? What, in particular, about his direct-to-tape works? In that case, it’s not possible to say where the line between the music and the recording should really be drawn – the recorded sound is the piece as performed by the composer. My view is that one needs to be pragmatic about these things, and that, in a world where expectations are high and listeners are used to a clear and spacious sound and a full frequency range, we ought to make these important performances available in a way that best serves the music and the listener. In a market as oversaturated as ours, what possible commercial basis could there be for a fantastically restored and re-mastered release of Johansen’s complete output? Perhaps outlets like Bandcamp offer a solution that can strike an enlightened balance between making the material widely available and generating income to support the project.

Composer Gordon Rumson has also led a huge effort to typeset over 75 of Gunnar’s compositions, ready for publication when funds are available. Letters and documents in the archives have been translated and put into order. So much has been done to put everything in place for a Gunnar 2.0 moment. It’s now time to make that moment happen.

Inevitably, when one is dealing with a personality as prolific as Johansen’s the question comes up of “was he really doing it all well, or just doing it all fast?” In his case, it’s not an easy one to answer. He did most of it very well, but Johansen is about as far as you can get from pianists like András Schiff, who spent about 20 years preparing his first performance of the complete piano sonatas of Beethoven. Johansen was obviously a phenomenally quick study, and there seemed to be something in him which made him want to share his discoveries with the audience as quickly as possible. The need for music to capture “the moment of inspiration” that drove him to create the Improvised Sonatas probably informed his approach to performance. In order to improvise, one has to accept that not every solo on a rhythm changes tune is going to be touched by God. So, yes, there is some unevenness in Johansen’s output. But make no mistake, at his best, his is some of the most powerful and awe-inspiring pianism ever put on disc.

Johansen was obviously an intellectual, but his approach to performance strikes me first and foremost as instinctive. On seeing his friend Paul Badura-Skoda’s score of a late Beethoven piano sonata heavily marked with annotations of all kinds, Gunnar told his student Colias that “I could never play a piece of music with so many fences around it.” His own personality is so strong that it emerges, whether bidden or unbidden, in all kinds of music. For instance, his approach to Bach, while tempered with a huge breadth of knowledge and research, was probably influenced first by the Busoni tradition he surrounded himself with as a young man. This may lead some modern listeners, accustomed to completely housebroken and well-mannered Bach to be rather nonplussed by the sheer sonority that he sometime unleashes in his fantastic recording of the Goldberg Variations, especially when he uses his Moór to add octave doublings. Although the intent is clearly to mimic the same effect on the harpsichord, the result does sound in a few places like Liszt on steroids. I love it. Fortunately, his sense of pulse and shape are incredible – not for him the mannered manipulations of tempo I hear from so many of today’s Bach pianists. His Bach has a true and healthy beating heart, and something of the spirit of a great improvisor.

The Legacy

Johansen was in one way unlucky to be about a century ahead of his time. He’d be perfectly in tune with the best of today’s Zeitgeist and today’s technology would have really given him a platform to achieve his vision without any sacrifice of technical standards. He could develop the networks of the Leonardo Academy through the internet, and publish their output for free online. His Music in Performance class could take its place alongside Jonathan Biss’s hugely popular online class about the Beethoven Piano Sonatas, a project taken, probably unknowingly, right out of Johansen’s playbook from 1939 onward. And everyone who, like me, has benefited from spending time as an artist-in-residence owes a huge debt to Johansen and his twelve historic piano recitals. And 2020-21 is really the age that Johansen seemed to predict – every time you see Igor Levit or Renaud Capucon giving a concert from their homes in lockdown, you’re seeing the natural outgrowth of what started when Gunnar borrowed that WHA tape machine back in the 1940’s. David Korevaar’s complete cycle of Beethoven sonatas from his living room last spring is about as “Gunnar” as it gets, right down to the chickens and cats in the back yard.

Fortunately, Gunnar may in some ways be the instrument of his own salvation. The world of electronic distribution he did so much to develop is now coming to his aid. While no recording company, nor even Gunnar’s own University of Wisconsin, have risen to the challenge of releasing his vast output, at least many good souls on YouTube have been busy uploading transfers of the LPs and cassettes, and you can hear the results of their efforts, alongside some very interesting interviews, in the epic playlist below. While Gunnar would have probably appreciated their energy and initiative, he would no doubt have been deeply dismayed by today’s ‘everything for free’ culture. Artist Direct was not funded by the University (although they did provide a great deal of support in instruments and recording gear), nor by any foundations. The entire enterprise of over 140 albums was funded on record sales – and virtually every penny that came in as revenue went back into pressing the next albums. Even now, if the Johansen Trust, which owns the copyrights on all of his recordings, were getting compensated for his music, we might be able to fund the work of making new recordings, building a proper Johansen website or commissioning new scholarship.

The true pioneers must accept that, when you go somewhere nobody has ever been, there’s nobody there to see you when you arrive or to bear witness to your achievement. It’s the job of historians, archivists and critics now to rediscover and make available the work of Johansen and other 20th Century innovators. Understanding their work will help us to make the next big leaps, and hopefully give inspiration to the next Johansen, and the conductor who writes in 2121 that “poor chap, he was born 100 years too early.”

A good start would be fund our recording of his orchestral music! Label, pianist, orchestra and conductor are all on standby!

In the meantime, in this age of home recording and technological distribution, here’s to Gunnar Johansen, the man of the year and the man of the hour.

A playlist of Gunnar Johansen. Lots to explore, but only the tip of the iceberg!

[1] The definition of ‘complete’ in all cases has to be pretty liberal and based on the availability of music at the time of the recordings. Of course, later series have been even broader in scope.

What a superb, informative tribute to this remarkable artist! Thanks.

Incredible artist and an excellent review of his life and contributions. Kudos to you and to Trustee Colias for advancing the legacy!

Kenneth, Your biography on Gunnar Johansen is great. It would a fine thing to add to the Wikipedia entry which is sad in it’s brevity.

I had the sincere pleasure to hear Gunnar in many post-“retirement” performances. His spoken comments were equally enlightening. As a student of Howard Karp and Ellsworth Snyder, I was fortunate to enjoy intimate company and conversations with Gunnar. After I played a”Live from the Elvejhem” concert on Wisconsin Public Radio, one of my happiest surprises was a voice mail message Gunnar left on my machine, commending my performance of Liszt’s 2nd Ballade and Funerailles! People speak about certain human beings in whose presence one is nearly blinded by their sheer white-hot light. This is what it was to be near Gunnar. These are magical memories for me that so many years later feel almost unreal in today’s plastic reality. Cudos to all of you entrusted with his legacy. I am available to help in any musical and organizational efforts. God Bless Gunnar Johansen.

This is an excellent piece, well-done, superbly written. Thank you. I was a good friend of Mr. Johansen’s Blue Mounds neighbors, John and Franny Newhouse, and the time spent telling “Gunnar stories” was always entertaining.

Fun Fact:

I was this Gunnar’s sound engineer in the mid ’70’s – I would work at his stone built Frank Lloyd Wright home in Blue Mounds, WI, and he would take off on my motorcycle while I was working – I had a Suzuki 750 4K back then and he no longer owned one – He and his wife would always get me drunk on good liquor, feed me a great meal and put me up for the night, even when I wanted to get back home that day

Fond memories – I later ran into him in the 80’s out in Gualala, CA, a little south of Mendocino – He was always like meeting an old friend

My student colleagues in the UW Symphony and I performed with Gunnar Johannsen in the mid-60’s in Music Hall. We were so excited to be asked and able to spend time playing with him. His knowledge and humor made this opportunity unforgettable.

(Except, unfortunately, I don’t remember the name ofpiece we played with him!)