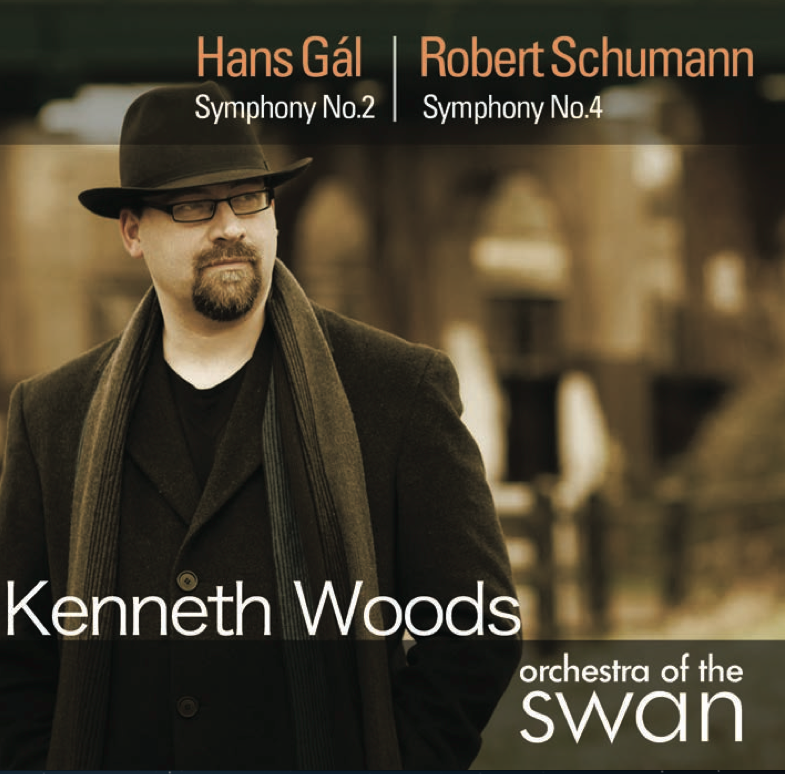

It’s time for the third instalment in our Explore the Score series on the Schumann symphonies. Our new recording of Gal’s 2nd Symphony and Schumann’s Fourth has just been released on Avie Records. Ordering via these links helps support these important recordings.

Explore the score: Schumann Symphony no. 1

Explore the score: Schumann Symphony no. 2.

Explore the score: Schumann Symphony no. 3.

Schumann: Symphony No.4 in D minor, Op.120 (final version)

‘If the Third Symphony represents Schumann’s closest approach to symphonic monumentality, the Fourth Symphony is his most ingenious experiment in form.’ Hans Gál

The work known to most modern listeners as Schumann’s Fourth Symphony was, in fact, the second he completed. After the huge success of his First Symphony in 1841 (the ‘Spring’), Schumann, with typical single-mindedness, forged ahead through the remainder of the year with his focus squarely on orchestral music. In the spring of 1841, he completed the Overture, Scherzo and Finale, then immediately, according to his wife Clara’s marriage diary, began work on a D minor Symphony on 31 May. While the Spring Symphony had poured out of him in practically a single gesture only months earlier, progress on the D minor was more sporadic, with entries in the Haushaltbuch noting numerous bursts of productivity and other periods where the work was set aside due to travel, illness or the urgency of other projects. Finally, Schumann declared on 4 October that he had ‘finished polishing the symphony.’

No doubt the summer of 1841 was a busy one, but there were sound musical reasons why Schumann might have needed more time to work on his new symphony. Although the ‘Spring’ takes interesting steps towards achieving symphonic cohesion through the cross-referencing of themes and motives across movements, the D minor was a radical new approach to symphonic form – a symphony in a single breath. Although Schumann had clearly fashioned the D minor Symphony after Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy, Schumann’s experiment in what he initially even called a ‘Symphonic Fantasy’ was, even in its first manifestation, more structurally ambitious than Schubert’s prototype, and would become, in time, a model for such revolutionary works as Schoenberg’s First Chamber Symphony and Sibelius’s Seventh.

The ‘Spring’ Symphony had been rapturously received at its premiere by the Gewandhaus Orchestra under the baton of Schumann’s friend Mendelssohn, but Mendelssohn was unable to conduct the premiere of the D minor Symphony, and the job fell to the orchestra’s concertmaster, Ferdinand David, who seems to have managed only a lacklustre job. Schumann expressed disappointment with the performance on 6 December 1841, but he was confident that the merits of the symphony (and the Overture, Scherzo and finale, first heard in the same concert) would soon be recognized: ‘I know they are not at all inferior to the First, and must succeed eventually.’ Certainly, many of the early reviews of both pieces were positive. If the premiere had not been a triumph, neither was it a catastrophe. Nonetheless, Peters Edition declined to publish the D minor as his Op.50, and Schumann set the work aside to attend to new projects.

He returned to his symphonic Cinderella in 1851. The success of his fourth and last symphony, the E flat major work published as his Third and dubbed the ‘Rhenish’ (a title Schumann never used nor intended) had renewed his enthusiasm for the genre, and he had also recently completed preparing the unfinished D minor symphony written by his friend, the recently deceased Norbert Burgmüller, for publication. Although Schumann spent only a week or so revising and re-orchestrating his own D minor Symphony, the changes are extremely important and telling, and all for the better: this is a revision undertaken by a master at the peak of his powers. Most importantly, Schumann attended to the transitions and connections between the different movements and sections of the work, making them more compelling and seamless. He refined the work’s orchestration for performance by the 45 or so musicians of his Düsseldorf orchestra or the Leipzig Gewandhaus, (not a modern symphony orchestra of over 80 players), and made other significant alterations, such as changing the meter of the first movement’s Allegro from the relatively heavy and insistent ‘in one’ to a more varied ‘in two’. The premiere of the revision (catalogued as Op.120) on 30 December 1852 was one of the last great public and critical triumphs of his career, and this time, he had no difficultly in finding an enthusiastic publisher.

In its final form, the first movement represents one of the most original re-imaginings of Sonata form of the post-Beethoven era. The slow introduction begins with a powerful multi-octave A pedal, not on the downbeat as one might expect (and as Schumann had written in the 1841 version), but on the upbeat. This metric dislocation is loaded with tension, and the theme that follows is notable for its economy of rhythmic and intervallic materials- it’s all in quavers and mostly written in step-wise motion. The transition into the movement’s main Lebhaft section is another significant improvement over Schumann’s original. Schumann replaces the original version’s somewhat formulaic fanfare chords, which don’t seem motivically well-connected to the preceding or subsequent material, with something far more fluid and organic. The continuous quaver motion of the melody metamorphoses into a growling bass ostinato, and the violins introduce the main theme of the Lebhaft, derived from the quaver theme, in semi-quavers. The exposition is extremely terse, and essentially monothematic setting the tone for the symphony as a whole. The development lurches from a jovial arrival in F major to a fortissimo unison E flat, dominated by the stentorian power of the trombones, and even introduces new and contrasting material previously withheld, something decidedly unexpected in a movement of this type. Only in the last third of the movement does Schumann introduce the lyrical second subject we might have expected much earlier, and this soaring theme provides the impetus for an ecstatic coda, which eschews any Beethovenian restoration of order and stability (note how all the accents and emphases fall on wrong or weak beats and bars).

To treat the following Romanze as a broad, big-boned Romantic slow movement is to misread both Schumann’s intent and his metronome marking. The lilting theme in the solo oboe and cello is modelled on a courtly Renaissance dance, and Schumann reportedly originally intended to double the pizzicato accompaniment in the strings with guitar or lute. Even the return of the symphony’s portentous introduction is notably fleeter and more fluid than in its first incarnation (albeit not in all performances. Such dalliances can be beautiful and convincing in the moment, but they surely take away from the sense of unity and direction which is so central to the D minor’s whole conception). As if to underline the sense of continuation and interconnectivity between the first and second movements, the following middle section, with its elegant violin solo, is actually a fairly direct variation of the symphony’s opening (and the reprise of it just heard), the violin triplets embellishing a cantus firmus in straight quavers and step-wise motion. The Scherzo offers an abrupt and violent contrast, while nonetheless growing organically from motives found in the symphony’s opening bars. The Trio, like the Introduction, is a study in continuous quaver motion, integrally connected to both the symphony’s opening and the violin solo in the Romanze, and is as dreamy and sensual as the Scherzo is violent and severe.

The transition to the finale shows Schumann completely at home in the dramatic world of high German Romanticism, with stormy tremoli and dramatic brass fanfares that might evoke memories of Weber’s Der Freischütz, especially the dark and brooding Wolf’s Glen. In the main body of the finale which follows, Schumann changes the meter from 2/4 to 4/4, and (in the revision) integrates the theme of the first movement with the triumphal new theme of the finale (an incredibly powerful link, which Schumann had not developed in the original). This is music that has often been subjected to the indignities of a comedy tempo. The brass chorale at the end of the exposition (repeated in the revision, not in the original, which tells one that repeats in Schumann’s time were anything but pro-forma) also originally appears in the first movement, and proves increasingly key in driving the symphony toward its destination. The structure of the Finale neatly parallels that of the first movement, gradually increasing in intensity as it adds new themes, but this time the musical journey heads surely towards the closure so emphatically avoided by the first movement, in an utterly characteristic meeting of Apollonian rigour and Dionysian ecstasy.

C Kenneth Woods, 2013

Recommended recording of the 1841 version- Thomas Zehetmaier, Northern Sinfonia, Avie Records

First minute from finale – change all music for me. I search in many symphonies this kind of climax. I find this in 4th Bruckner Finale (Celibidache) also Bruckner 3th opening, Liszt’s Faust and some Wagner overtures. It will be great if you will reveal your Favorite moments in symphonies.

A lot of Mendelssohn undercurrents…