It’s that time of year again, when musicians all around the world are taking another stab at Handel’s Messiah. For me, it means coming back to a piece I’ve done many times after a long-ish break.

I didn’t always love Messiah. In fact, when I first encountered it, I really disliked it. In my small-minded way, I couldn’t help but compare it damningly with Bach’s Saint Matthew Passion, a piece I’d always loved and knew more intimately. (For all the complexity of his music, I think Bach is one of the easiest composers to “get.” I can’t think of any Bach piece I couldn’t tell was a work of genius the first time I heard it, no matter how awful the performance or how discombobulated my thinking. I can’t think of another composer I can say that about). There are still moments in the libretto of Messiah that really bother, even upset me.

Of course, recognizing that a piece of music is not as great a work as the Saint Matthew Passion is no great act of critical discernment- the same could be said of every other piece of music ever written with the possible exception of the Schubert Cello Quintet and Bohemian Rhapsody.

Eventually, however, if one has ears to listen , one realizes that a piece you might not have loved on first sight is good- maybe even great.

Then, you start figuring out why it is great, and the more you figure out, the greater you realize it is. For a conductor, this is about the time that you seriously start itching to “do” the piece, and through study and performance, you hope to find a sort of beneficial cycle of practical experience and genuine insight.

Long time readers of this blog will recognize that I’m a big believer that as musicians, we owe the composer the benefit of the doubt. As often discussed on these pages, any idiot can see that the “invasion theme” in Shostakovich’s 7th Symphony is pretty repetitious, and rather obviously “un-symphonic.” After all, he’s replaced the development section of a symphony with something two or three times as long as a “normal” development section in which essentially no development takes place. I’m amazed that many good musicians still can’t seem to get past this- it seems obvious that Shostakovich knew he was breaking the rules. Don’t we owe him the benefit of the doubt to find out why? When a great composer frustrates us, when the music disappoints our expectations, there’s usually a very good reason.

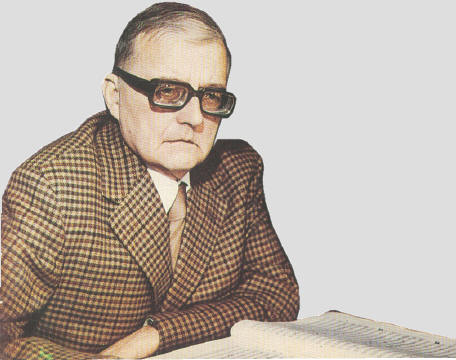

Dmitri Shostakovich- you’d be amazed how many people come to this blog just looking for a picture of Mr.DSCH

Back when I didn’t care for Messiah, one of my gripes was that so many movements seem to cover awfully similar musical territory. As I’ve grown up, I’ve come to understand that what at first seems like torturously pointless repetition is really an extremely sophisticated large-scale structural plan that is actually, in a way, quite symphonic (I’m talking about Messiah, not Shostakovich 7). This time around, I’ve been particularly struck by the way that the big ideas of the piece emerge from the fabric of what comes before. There’s possibly no more galvanizing-ly powerful moment in choral music than the bit in the Hallelujah chorus with the sequence “And He shall reign.” How interesting that the musical substance of that passage has long been coming into being, evolving gradually from near the very beginning of the work, with the similar descending sequence in “Let all the angels of God worship Him” and the rising fourths to the word “goodwill” in “Glory to God” marking major landmarks on the road to this moment.

Of course, 99% of the people who hear this music at all hear “Hallelujah” long before they hear any other part of Messiah (if they ever get beyond “Hallelujah” at all), and yet, to me the sort of super-charged joyful intensity that particular passage has in “Hallelujah” seems to be somehow informed by the journey that precedes it. A listener hearing the chorus for the first time won’t know this, but just about everyone seems to sense that there’s something about this music that is suffused with energy.

The opening of “Hallelujah” used to kind of mystify me, too. The first three bars seem so ordinary (and so many performances of them sound so WOODEN)- they just sort of trot along with a kind of inside-out, non-descript wordless version of what will become the “Hallelujah” theme. Why didn’t Handel come up with a more dramatic opening? And why only three bars? Surely a four-bar intro would have been more powerful- was he just being fancy? Lazy? And why not let the violins play the real theme? I always think it’s funny that audiences traditionally stand as soon as the movement starts- surely it’s the music in the fourth bar, when the choir sings the first “Hallelujah” that should make you want to jump out of your seat. Conductors so often seem wrong footed by these three bars, as if we don’t really know what to do with them. Many go for the “just try something” approach- we might try the “amp up the pomposity” approach or the “show ‘em your Birkenstock’s” extra-HIP version. Handel doesn’t help- there’s no dynamic in the intro, nor is there one for the entrance of the chorus. There are lots of possibilities, but I’ve also heard a lot of unsuccessful stabs at “the REALLLLLLY soft opening” or “the conspicuous crescendo.” Let’s face it, whether you bulk it up with Brucknerian steroids or make it extra mincy, it’s just three bars of medium tempo trotting with the tune turned inside out.

Yet Handel, who knew a thing or two about drama having written who-knows-how-many operas (forty-two or forty-six depending on what you count) by this point in life, knew exactly what he was doing, which is obvious if we give him the benefit of the doubt. This sort of seemingly non-descript “trotting” music has actually permeated the work up to this point. That was always one of my problems with the piece when I was young and taking in the work one movement at a time. When you’ve just heard “And he shall purify,” doesn’t “For unto us a Child is born” sound eerily similar? Medium temp, jolly, trotting eighth-note groove, a melody in moderate note values and a bit of sixteenth-notey coloratura. Then there’s “His yoke is easy.” Similar tempo, similar tune, just a slightly jazzier flourish to those sixteenth-notey runs. Fast forward a few tracks, and you’ve got “All we like sheep.” Sure it’s funnier than the others, in ways both intentional and unintentional (sheep jokes just get funnier and funnier the longer I live in Wales), but it’s still that same trotting bass line, the same mid-tempo grove, with thematic gestures similar in length and shape to those in “For unto us.”

I’ve certainly heard MANY performances that left me thinking that Handel was probably just trying to cover all this theological bases with some thinly spread recycled stock musical ideas, but experience teaches that the failing in these cases was in the performance, not the piece. Over the years, I became convinced that a lot of this was to do with tempo and put a lot of thought into making sure that I wouldn’t fall into the “universal tempo” trap, trying to highlight the differences between these admittedly similar movements, and actively seeking out the textual motivations for those differences. This time, however, I’m realizing that for all it’s important to do that (like most music lovers, I have come close to chewing my own arm off to relieve the boredom during an ill-conceived Messiah), it’s also important for me to realize that Handel, the dramatist, knew what he was doing, and that the similarities are very much part of the point. Those similarities are obvious, so it’s likely they’re both intentional and important. Why?

All of these choruses seem to be on one level about expectation, about the promise of divinity. They all sing about what humanity hopes or expects or believes divine intervention will bring to the world.

If you’ve had this idea of expectation in mind every time you’ve heard those seemingly banal trotting eighth notes over the previous 90 minutes, then surely those first three bars of “Hallelujah” can be seen as literally bursting with anticipation, with tension, with barely contained joy. After all the waiting, after all the hoping, the endless expectation, in these three bars we’re literally standing on the threshold of the vision the piece has been seeking throughout. Of course, I can now see why the choir comes in after just three bars- this close to the moment in which the biggest of all promises is fulfilled, nobody could expect them to wait one moment longer, let alone a fourth bar.

Recent Comments