‘When his time to reach for the stars had arrived, Schumann’s personal language was fully formed, and just as the subtlety of his piano style had been an immense asset for the songwriter, so the expressiveness of his vocal melody was a bridge to the ‘voices of men and angels’ he imagined he heard in the orchestra.’

Hans Gál: Schumann: Orchestral Music

Robert Schumann wrote his First Symphony in an astonishing burst of creative energy over four days in January 1841, the focal point of a process of learning, planning and revision that stretched over a decade and more.

Schumann articulated his symphonic ambitions as early as 1829 to his teacher, future father-in-law and nemesis, Friedrich Wieck in 1829. ‘If you only knew how I feel driven and spurred on, how my symphonies could already have reached opus 100 if only I had written them down, and how comfortable I feel with the orchestra…’ Within three years, he had completed the two movements of the G minor ‘Zwickau’ Symphony, which were performed in 1832–3. Throughout the rest of the 1830s, Schumann wrote only for the piano, but from 1933, he was studying scores of the Beethoven symphonies and pursuing studies in score reading and orchestration. His eventual marriage in 1840 to Wieck’s daughter Clara, against Friedrich’s strenuous objections, became the catalyst for a change of direction: this ‘year of song’ included the composition of 168 lieder and shaped Schumann’s music for the remainder of his career, throughout which the singing line would always remain paramount.

Crucial to his emergence as a symphonist was Schumann’s chance discovery, on a visit to Vienna in 1838, of the score of Schubert’s ‘Great’ C Major Symphony: ‘It opened up to me all the ideals of my life. It is the greatest instrumental work to have been written since Beethoven…. It spurred me on again to attempt a symphony…’. He duly pressed the symphony on to his friend Mendelssohn (then director of the Gewandhaus in Leipzig), who gave the belated premiere in March 1839.

In 1842 Schumann advised the conductor Wilhelm Taubert: ‘Try to infuse some longing for spring into the playing of your orchestra; this is what I felt when I wrote it…’ For Schumann, perennially susceptible to literary inspiration, that longing found voice in a poem by Adolf Böttger, and particularly its last stanza:

O wende, wende deinen Lauf—

Im Thale blüht der Frühling auf!

O turn, O turn and change your course—

In the valley spring blooms forth!

Böttger’s poem unleashed Schumann’s symphonic imagination, and in those famous four days of ‘symphonic fire… sleepless nights,’ what he achieved is awe-inspiring. On 26 January he wrote in the Household Book ‘Hurrah! Symphony completed!’. He orchestrated the symphony in February and made further revisions having gone through the score with Mendelssohn, who conducted the first performance with the Gewandhaus orchestra on 31 March to critical enthusiasm: the Allgemeine Musikaische Zeitung praised the ‘intellectual and technical sureness and skill with which it was conceived and… tasteful and frequently felicitous and effective orchestration…’

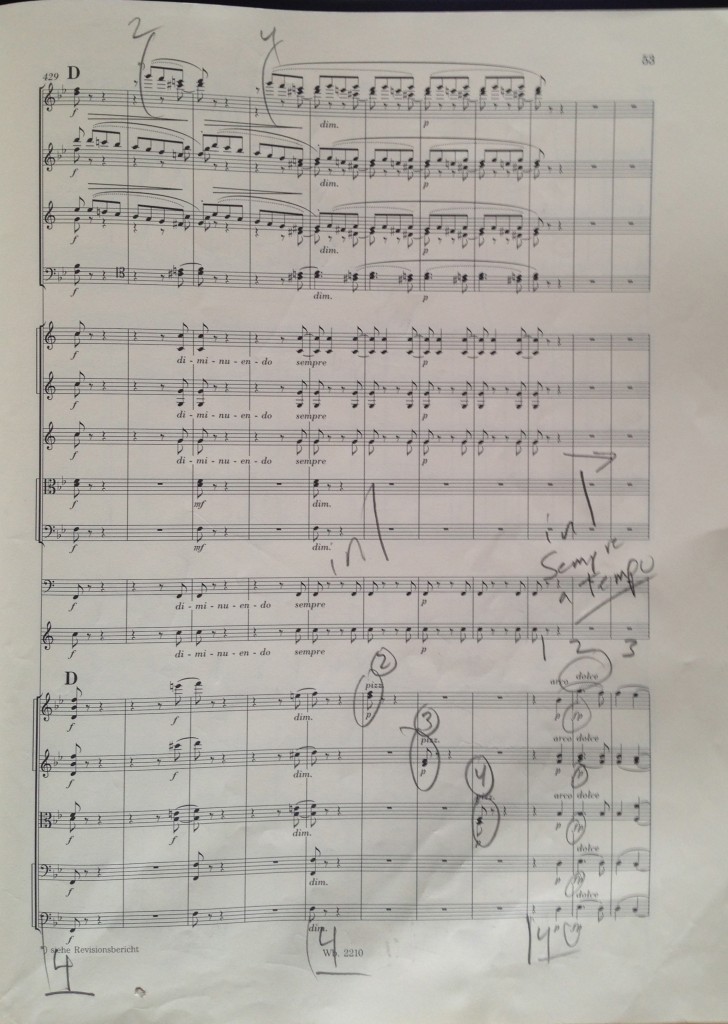

By the time Breitkopf published the full score over ten years later in January 1853, Schumann had made various further revisions, mainly in matters of tempo (there exist four sets of metronome markings- see post script) and orchestration, less radical than his work on the D minor Symphony which he had written immediately after the ‘Spring’ but is now known in its final version as the Fourth. It is remarkable that these two works, both written in 1941 and revised in 1851–2, would later, wrongly, become prime pieces of evidence in the case against Schumann’s orchestration in his later years. Gál felt that the final orchestration of the D minor ‘is hardly a success, thickening the texture by over-generous doublings…the most drastic illustration of Schumann’s problematic experience as a conductor.’ On the other hand, the ‘Spring’ Symphony, the orchestration of which reached its final form only after the D minor (see post script below), is hailed by Gál as ‘the most fortunate of Schumann’s symphonies in the first impression it makes…the most successful use of orchestral colour that Schumann ever succeeded in obtaining.’ Gál would have had few chances to hear either work performed by a group of similar size and cohesion to the 45-member Gewandhaus Orchester of Schumann’s day. Heard in a similar setting (we’ve used an orchestra of near-identical size and layout), the two works reveal a similar mastery of colour and transparency of texture.

http://youtu.be/uvc2hlvEDiM?t=1m57s

The musicians of Spira Mirabilis sing the opening of Schumann’s First Symphony to the text which inspired it.

The symphony’s opening brass fanfare is an instrumental setting of the last line of Bottger’s poem, from which much of the symphony will develop.

Böttger’s poem begins not with the joys of spring but with a depiction of winter storm clouds, and so it is for much of the Introduction, which contains the most radical music in the symphony.

Du Geist der Wolke, trüb und schwer

Fliegst drohend über Land und Meer

Dein grauer Schleier deckt im Nu

Des Himmels klares Auge zu,

You spirit of the clouds, grey and heavy

Looming over land and sea

Your obscure veil obscures in a frozen moment

The clear eye of heaven

This primitive music would later serve as inspiration for Mahler’s own depiction of spring’s awakening in his Third Symphony.

http://youtu.be/caApW1QOmTU?t=2m44s

Spring Marches In, with epic directorial choices by someone at Dutch TV

Music may not often precisely mirror its composer’s state of mind, but surely it is no accident that the Allegro of this first movement, possibly Schumann’s most joyful span of music, comes from the happiest time of his life- settled in a new and happy marriage, in good health and finally writing the symphonic music he had long aspired to. The main theme, which we hear throughout the movement as both melody and ostinato, is basically the opening fanfare sped up:

The final third of the movement has a shortened recapitulation and a coda with two notable features- a new tempo and a new theme. At the beginning of the coda, Schumann marks “Animato- poco a poco stringendo.” Literally- “animated, and little-by-little getting faster.” But how long to increase the speed for, and to what final speed?

Then there is the new theme. One of Schumann’s signature touches as a composer is his habit of introducing a new theme right before the end of a movement or even a piece- a sort of “breakthrough” or “apotheosis” theme. In the case of the the Spring Symphony, the breakthrough theme (one of his most stunning) is almost always played slower than not only the Animato tempo, but slower than the whole rest of the Allegro. It’s such a well-established tradition that I was more-than-a-little surprised when I first saw a score that no such tempo change was marked. Over the years, my skepticism about this unmarked tempo change grew and grew, although Schumann is not a composer who offers much safety in the simplistic world of pure literalism. As with good cooking, you should understand and follow the recipe given, but must taste what you’re making as you go. Similar breakthrough themes in other Schumann pieces generally don’t get slowed down, and in this case, the prevailing rhythm already shifts from eighth notes to quarter notes. On the other hand, plenty of great conductors (nearly all) and orchestras do the traditional slow down, and find their own paths to a final (faster) tempo for the movement. In fact I don’t think I ever heard a performance without the meno mosso until we recorded the piece (although I’m sure we’re not the first ones to omit it- I’ve only heard a small number of the many dozens of recordings of the piece).

Sawalisch, whose Dresden set is the classic large-orchestra Schumann cycle, slows very little, but is generally in a much slower tempo overall.

http://youtu.be/eFFq2F0ldW0?t=8m39s

Maestro Nezet-Seguin takes a little rit into the breakthough theme, slows down just before the end of the section, then has the solo flute lead a little accel into the final restatement of the fanfare

http://youtu.be/EkSVTJ598uQ?t=8m47s

Maestro Zinman does comparatively little Animato, and makes less of a gear change at the breakthrough theme, but does quite a big rit before the final fanfare, which is in the tempo of the main movement rather than in an Animato tempo

http://youtu.be/VFvNriIDLrs?t=8m58s

Maestro Leonard Bernstein does a fairly extreme tempo buildup over the Animato, and huge rit to the breakthrough theme, which is less than half the speed of the rest of the movement, before a second rit leading into the clarinet tag and a third rit in the solo flute bars. The return of the fanfare is a tempo, and he drives through to the end

http://youtu.be/uvc2hlvEDiM?t=17m14s

The conductor-less orchestra, Spira Mirabilis, do quite a zippy accel in the first 20 or so bars of the Animato, before putting the breaks on pretty hard at the breakthrough theme, with a rit from the last few bars of the clarinet tag and the flute solo before a final a tempo, which lands somewhere between the main tempo of the movement and the highpoint of the Animato tempo

Maestro Paavo Jarvi with the Israel Phil- starts more or less in the Animato tempo, but slows down quite a bit as it goes on

In the end, I chose to read the “Animato: poco poco stringendo” as a gradual increase in tempo, and went to some trouble to try to make that increase carry on until the breakthrough theme. That, to me, marks the end of the accel. At that point, I also switch from conducting “in two” to “in one.” It’s important to note (confess) that although I’m not inserting two or three extra tempo changes in this reading, I’m also not being strictly literal, either. A totally literal reading would accel gradually to the end of the movement (as if he’d written Animando sempre al fine). In the end, however, I feel like this was the the reading that most seemed to suit the music for us. The change of pulse from” in two” to”in one” creates a sense of space and even ecstasy for the breakthrough theme without creating the problem of find one’s way back to the fast temp for the end (which we do “in two”.

_____________________________________________________________________

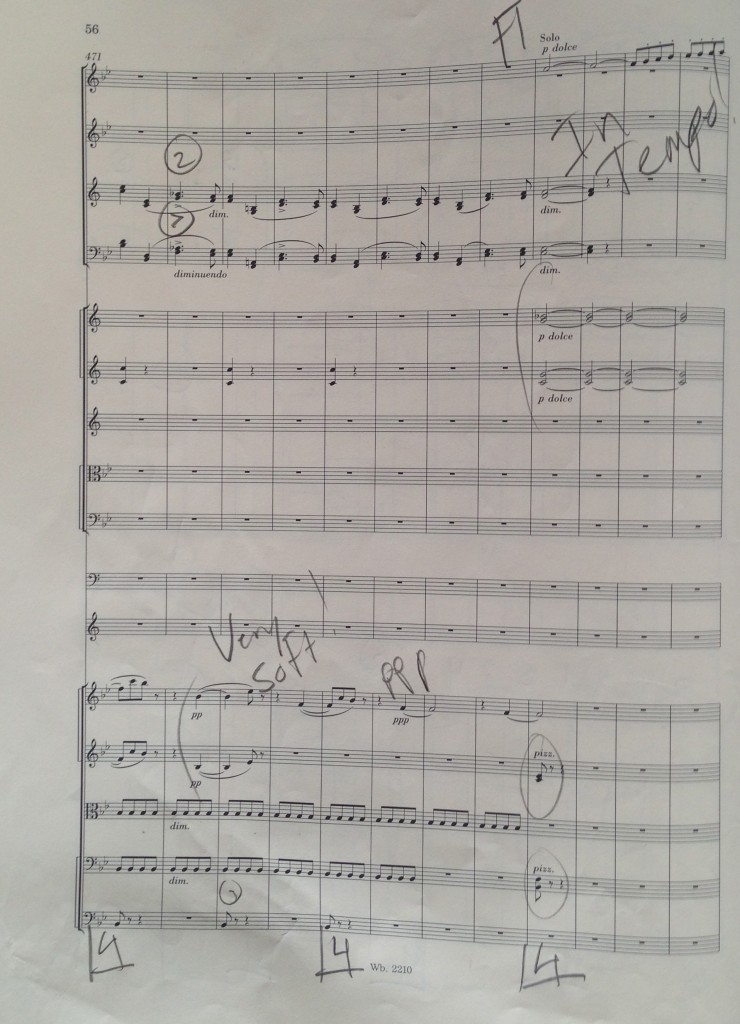

The lyrical Larghetto, which Schumann left almost untouched during the process of revision, is the offspring of his ‘year of song.’ It’s the only movement in the Symphony for which Schumann never adjusted or amended his metronome marking of quaver=66

On the final page of the Larghetto, the trombones, who have not played since the first movement, enter pianissimo with an eerie foreshadowing of the theme of the upcoming Scherzo. Moments like this and the famous (insanely high and exposed) chorale at the beginning of the fourth movement of his E-flat Major Symphony (often referred to wrongly as the Rhenish) would seem to indicate the Schumann had at is disposal a trombone section with nerves and chops of steel. Luckily, we had a similarly gifted team in Stratford for these sessions.

_______________________________________________________________________

The Scherzo returns to the wilder world of D minor hinted at in the symphony’s Introduction.

The first of two witty trios is in duple meter-

Schumann omitted a metronome mark for the second trio, which poses a conundrum for the conductor: played at the same, brisk speed as the first trio, it creates a rather Mendelssohnian effect. Mendelssohn worked closely with Schumann on the Spring and conducted the premier. To me, the relatively slow harmonic rhythm and symmetrical phrase structure argue strongly for that approach. Here’s how we did it on the CD:

At the tempo of the main Scherzo, it can sound more rustic.

http://youtu.be/EkSVTJ598uQ?t=20m18s

Maestro David Zinman takes the slower of two possible tempi in the third movement of Schumann’s Spring Symphony

Having begun in such a furious mood, the Scherzo ends with a a whimsical look back at the music of the first trio: a flirtatious flitter of syncopations, crowned with a musical kiss.

_____________________________________________________________________

Schumann told later told Wilhelm Taubert that ‘About the last movement, I can tell you that I envisage spring’s farewell and hope that it is not taken too lightly.’ Certainly, nobody would be tempted to take the opening gesture too lightly- it storms in on the music which ends the Scherzo like an angry father catching his daughter getting into mischief with her boyfriend. Or maybe it’s just a triumphalist fanfare? You decide:

The main theme of the Finale is a quirky and virtuosic scamper:

While the second theme is based on that opening gesture (fanfare or tirade, you decide).

It’s also a quote from the final section of Schumann’s earlier piano piece, Kreisleriana:

Schumann sets himself a serious challenge with this Finale- how is one to surpass the thrilling energy of the end of the first movement so that the end of the symphony doesn’t feel like an anti-climax? Schumann’s solution is both simple and inspired- repeat the same formula, a Coda section built around a long accelerando, but up the stakes even further. It takes huge concentration and commitment to mange this long buildup without running out of gas. The version you hear at the end of the CD is taken whole from the concert which marked not only the end of the sessions not only for this disc, but for the entire four-year Bobby and Hans project How funny that we finished the cycle with the movement Schumann called “Spring’s Farewell.” It documents a very special and poignant moment in our shared journey as colleagues. If you want to hear the final few bars, please buy the CD.

C Kenneth Woods, 2014

________________________________________________________________

An additional note on the revisions of these first two Schumann Symphonies might be of interest. I find it baffling that the revision of the Spring (done after that of the D minor) is almost completely unknown, but they revision of the D minor remains so controversial among those who don’t understand Schumann’s music or orchestration. It has been fashionable for some years to perform the original 1841 version of the D minor in spite of Schumann’s clear preference for the original. There have been attempts to recreate the original version of the Spring using the parts made for the premier (which still exist), but it’s never caught on. I detect a double standard! The revision is also the source of the expansion of the timpani part and Schumann’s introduction of a third drum.

With thanks to Allan Stephenson, here is a listing of all the existing metronome markings for Schumann’s Spring Symphony which we can attribute to the composer:

The Piano duet (1842):

I. Andante crotchet =76 Allegro crotchet =152

II. Larghetto quaver=-66

III. Molto vivace dotted mimin =138 Trio 1 minim =144 and no marking forTrio II

(N.B. the scherzo 138 is way too fast but as is usual with RS’s writing could be 108)

IV. Allegro animato e grazioso minim =116

The manuscript full score in the British Museum:

I. Andante crotchet = 76, Allegro crotchet =152,

II. Larghetto quaver= 66,

III. Molto vivace dotted minim=138 Trio I Minim=144, Trio II none

IV. Allegro animato e grazioso minim= 116.

The manus. full score in the Archive der Musikfreunde, Vienna has

I. Andante crotchet =76, Allegro crotchet =132,

II. Larghetto quaver= 66

III. Molto vivace dotted minim= 138, Trio 1= 144, Trio 2= none

IV. Allegro animato e grazioso minim=116

The full score of 1853 has

Mvt I Andante crotchet = 66, Allegro molto vivace crotchet=120

Mvt II Larghetto crotchet= 66

Mvt III Molto vivace dotted minim=88,Trio 1, minim=108, Trio= none

Mvt IV Allegro animato e grazioso minim= 100

Recent Comments