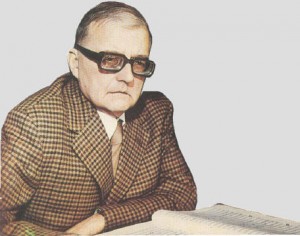

Dmitri Shostakovich’s Chamber Symphony opus 110a, an arrangement for string orchestra of his String Quartet no. 8 in C minor, opus 110, was the first of five orchestral transcriptions of his string quartets by his friend, the violist and conductor Rudolf Barshai. Shostakovich’s Eighth String Quartet stands at the centre point of his fifteen works in the genre. Shostakovich’s contribution to the string quartet repertoire stands alongside that of Béla Bartók as the most important addition since Beethoven’s mighty sixteen quartets. Shostakovich wrote the Eighth Quartet in the astonishing span of just three days between the 12th and 14th of July, 1960 while in Dresden working on the soundtrack for the film Five Days, Five Nights—a film about the Allied firebombing of that levelled that city in the closing months of WW II. When the work was published, its roots in Dresden were underlined by its dedication “To the victims of war and fascism.” Many early listeners detected all sorts of musical evocations of the city’s destruction. (I even know of one American conductor who, in an act of chutzpah and genius, persuaded the great novelist Kurt Vonnegut to read selections of his own tribute to Dresden, Slaughterhouse Five, at a performance of the Chamber Symphony version of the quartet. Any excuse to hear Vonnegut read his own prose!).

Leningrad as seen by photographer Alexey Titarenko. His images, inspired in part by the music of Shostakovich, will be included in our upcoming Avie recording

However, the true meaning and origins of this unique work gradually rose to the surface. Shostakovich was notoriously grudging in revealing anything about his music’s inner symbolism to even his closest friends, but in the case of the Eighth Quartet, he confessed early on that “I started thinking that if some day I die, nobody is likely to write a work in memory of me, so I had better write one myself.” To his son, Maxim, he said, simply “it’s in my honour, dedicated to me.”

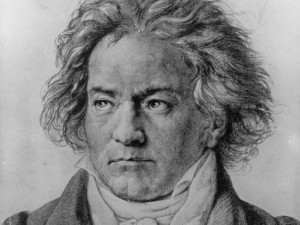

The confessional nature of the quartet is made explicit in its first four notes—Shostakovich’s musical motto DSCH, or D, E-flat, C, B. This motive first began to appear in disguised form in his Jewish-inflected Fourth String Quartet in 1948, later becoming the triumphant theme of his Tenth Symphony, premiered and published just after the death of Stalin in 1953. Never before, however, had Shostakovich opened a work with this motto, nor treated it with such intensity. The hushed, forlorn and fugal atmosphere of the opening evokes that of the opening of Beethoven’s greatest string quartet, his Opus 131 in C-sharp minor (the two works also have many structural similarities).

Beethoven’s model shows him at his most intimate and confessional, and so, too, it is Shostakovich’s response.

It is not, however, only the DSCH motto which underlines how personal this work was. Early in the first movement, Shostakovich quotes the opening of his First Symphony, the work that had launched then 19-year-old composer to international superstardom.

What had been cheeky and mercurial in 1926 has become deeply tragic and resigned by 1960.

A page later, he quotes his own Fifth Symphony, the work that had marked the central turning point of his career, and the most tumultuous point in his fraught relationship with Stalin and the Communist Party.

This musical quote points to a key biographical detail of Shostakovich’s life in 1960. After standing outside of the Party’s ruthless apparatus for his entire career, Shostakovich was finally forced to join the Communist Party that year, a step that caused him great personal shame and emotional distress. In fact, such was Shostakovich’s anguish that his friend, the musicologist Lev Lebedinsky, reports that “he thought it would be his last work—hence the self-quotations and the inclusion of a funeral march… A few of the composer’s friends knew that after finishing the work, Shostakovich had intended to kill himself; luckily they managed to persuade him not to do it.” Shostakovich went so far as to not attend the Party ceremony at which he was to be inducted- an act which could have been suicidal in and of itself.

After the meditative opening Largo, the second movement is a study in violence and madness, culminating in a screaming quotation of Shostakovich’s famous “Jewish Theme” from his Second Piano Trio. Jewish music held a special place in the composer’s heart, and he is quoted as having said that “Jewish folk music is close to my idea of what music should be… Jews were tormented for so long that they learned to hide their despair. They express their despair in dance music.”

There is more madness in the third movement, with the DSCH motive now twisted into a macabre waltz- it is as if the composer is mocking himself.

This movement also includes a quote from the opening of Shostakovich’s recently-completed First Cello Concerto.

[Only many years later did Shostakovich reveal that that piece includes a demonic-sounding reference to Stalin’s favourite folk-song, Suliko.]

The fourth-movement is another Largo, but has elements of both fast and slow music. It begins with three short, savage chords in the strings, “And the knocks on the door by the KGB,” said the composer’s son Maxim, “you can also hear them here.”

This gesture has a second meaning, as it is also a reference to the opening of the last movement of Beethoven’s final string quartet (his last completed work). Beethoven underscored these three chords in his work with the words “Muss es sein?” or “Must it be?”

Lebedinsky tells us that Shostakovich intended this to be his last work, too, and this gives this quotation particular existential power. Beethoven answered his own quetsion “Es muss sein!”(“It must be!”).

Again, Shostakovich quotes the theme of his First Cello Concerto, those four now-famous short notes now presented slowly and with terrible intensity. In fact, this theme was first used by the composer in a scene called “The Death of the Heroes” from his score to the movie The Young Guard in 1947-8.

Here is how it sounded in The Young Guard:

There follow two more devastating quotations- first of the revolutionary song “Tormented by the Horrors of Prison.”

Then, in the solo cello, a quote from the Act 4 of his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk. This scene in the opera is the one in which Katarina graps the depth of her betrayal by her beloved Sergei. Already condemned for the murder of her husband, she now realises the man for whom she sacrificed everything has forsaken her, and she throws herself into the icy waters of a Siberian river. Katarina, of course, took Sergei’s lover Sonetka, to her grave with her.

http://youtu.be/kAg1jZVgNy0?t=38m56s

(aria begins at 40:09)

Here, this music is transformed to announce Shostakovich’s planned suicide- he intended to go to his death alone.

The fifth movement is another Largo, returning full circle to the soundworld of the opening, with a complete fugue on the DSCH motive. The final quote, again of his First Symphony, brings a life’s journey heartbreakingly full circle:

The work was premiered by the Beethoven String Quartet, but it was Shostakovich’s habit to organize a private reading of his quartets with his young colleagues in the Borodin Quartet. When the Borodin’s played the Eighth Quartet through for the first time at the composer’s house, their first violinist Rostislav Dubinsky reported that “We finished the quartet and looked at Shostakovich. His head was hanging low, his face hidden in his hands. We waited. He didn’t stir. We got up, quietly put our instruments away, and stole out of the room.”

________________________________________________________________

Copyrighted recordings are excerpted here under Fair Use provisions of international copyright law.

Beethoven- String Quartet in F major, opus 135 performed by Masala String Quartet (Kio Seiler, Eva Rosenberg, Sheridan Kamberger, Kenneth Woods. Produced by Andrew Hasenpflug

Shostakovich 8th Quartet performed by the Borodin String Quartet

Great article Ken. I knew all of what you stated except for that Shostakovich meant for this to be his final work. That hit me hard. Thank God it wasn’t and we had 13 more years of productivity out of him. Imagine no 15th Quartet…no Viola Sonata…no Violin Sonata…no 14th Symphony. Ackkk!!! I can’t even imagine…