NOW AVAILABLE

As many of you know, all of us at the English Symphony Orchestra are busy gearing up for our 2015 Elgar Pilgrimage from the 7th-10th of October, with concerts in some of Elgar’s favourite haunts: Hereford, Malvern and Birmingham (on October 9th and 10th)

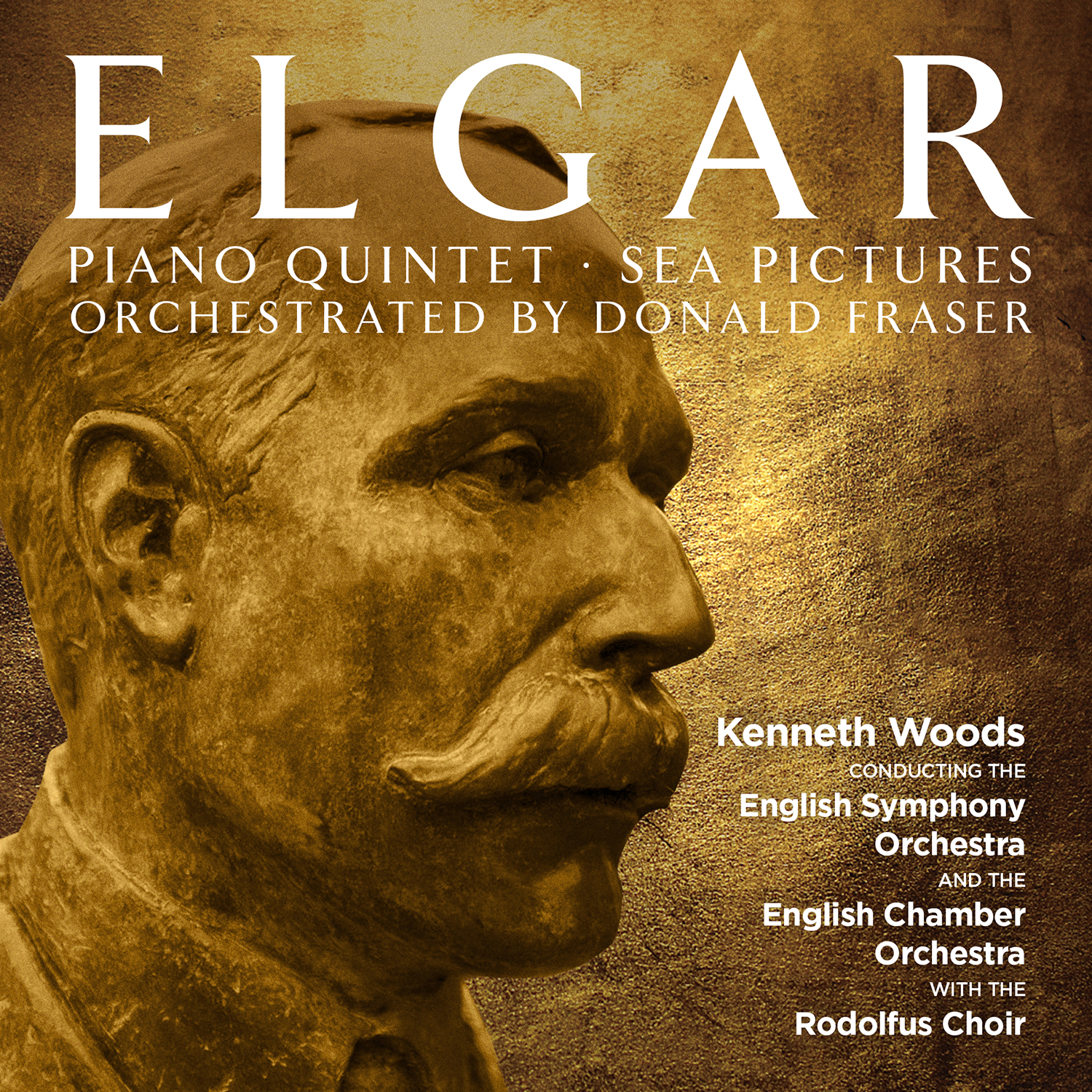

One of the highlights of the festival promises to be world premieres of two new arrangements of major Elgar works by composer Donald Fraser. On the 7th of October, we premiere his arrangement of Sea Pictures for chorus (no solo voice at all) and string orchestra, then on the 10th, we premiere his version of the Piano Quintet, now recast for full Elgarian symphony orchestra.

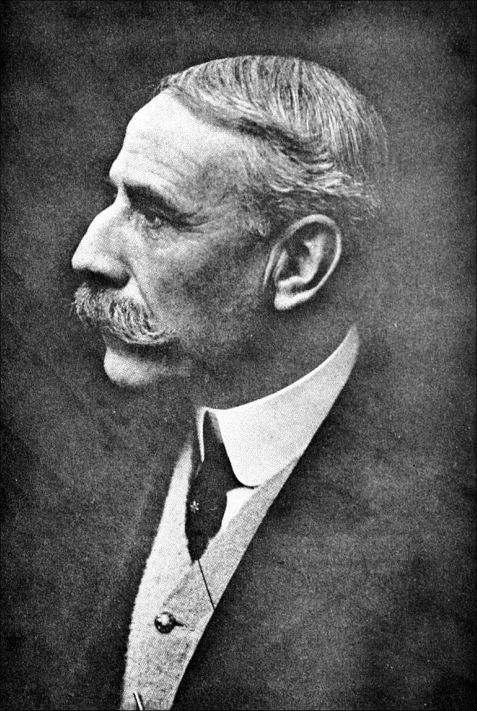

It’s been really gratifying to see the overwhelmingly positive reaction to the entire program of the festival, but one or two people (including someone I respect enormously) have expressed scepticism about the relevance of new arrangements of the music of Elgar. I was even a little surprised to find that the Elgar Society won’t fund performances of arrangements of Elgar’s music. I thought the subject of arrangements is interesting enough that it merited discussion here.

(Elgar didn’t write this piece, but I can’t tell- can you?)

Of course, Elgar was no puritan when it came to arrangements. He was very happy to see some of his highly profitable salon pieces arranged for all sorts of ensembles and instruments, and pieces like the Pomp and Circumstance marches have been adapted for brass bands almost since the ink on the originals was dry. Elgar was also happy to put on his orchestrator’s hat and work with the music of other composers, and he was not shy about putting his own strong stamp on other composers’ music. The stirring version of “Jerusalem” which ends the Last Night of the Proms every year sounds far more like vintage Elgar than anything else in the catalogue of its composer, Hubert Parry. In the twilight of his career, when his compositional inspiration waned, Elgar made a fantastically over-the-top arrangement of Bach’s Fantasia and Fugue in C minor, which we’ll play on the same concert as the Piano Quintet. Elgar was liberal in his use of all sort of effects completely alien to Bach’s original, from harp glissandi to percussion crashes:

‘I decided to orchestrate…in a modern way – largest orchestra…so many arrangements have been made of Bach on the “pretty” scale and I wanted to show how gorgeous and great and brilliant he would have made himself sound if he had our means. You will see that I have kept it all quite solid (diapasony) at first; later you hear the sesquialteras and other trimming stops reverberating and the resultant vibrating shimmering sort of organ sound.’ Edward Elgar

(Andrew Davis conducts the BBC Symphony in Elgar’s radical orchestration of Bach’s Fantasia and Fugue in C minor)

Of course, few composers were as prolific as Bach when it came to adapting, arranging, recycling and re-orchestrating all kinds of music- his own, his colleagues and his predecessors. For Bach, transcription an essential tool for personal study, and pragmatic way of coping with a diverse array of deadlines and demands, and as normal and natural an instinct as breathing.

Elgar was also extremely pragmatic about the orchestration of his own music, especially in the recording studio, as one can see from the pervasive use of the tuba to double the bassline in his early recording of Sea Pictures.

(Dig the tuba, and the unsentimental tempo!)

In fact, Elgar lived and worked in a golden age of arrangements and adaptations. His musical cousin and almost-exact contemporary Gustav Mahler was vigorously engaged in adapting and tweaking the works of his heroes for the realities of the modern audience. In an age when audiences for chamber music were dwindling, he adapted Beethoven’s great F minor String Quartet, the Serioso, and Schubert’s Death and the Maiden Quartet for large string orchestra.

(Kenneth Woods and the Rose City Chamber Orchestra play Mahler’s orchestration of Schubert’s Death and the Maiden quartet)

He was also unapologetic about adapting the orchestration of earlier composers, particularly Beethoven and Schumann, for larger halls, new instruments and larger orchestras. In doing so, he was carrying on a tradition manifest in Mozart’s re-orchestration of Handel’s Messiah and Mendelssohn’s cut and re-orchestrated St Matthew Passion of Bach. It’s important to note that there was no criticism of these earlier masters implicit in Mahler’s re-working of their scores for radically different acoustic realities, and that modern research has shown that Beethoven and his contemporaries were also more than comfortable with adapting to varying orchestral forces and performing spaces. We now know that in Beethoven’s time, performances of his symphonies with large orchestra almost always involved the selective doubling of woodwinds and even tutti vs reduced string sections to maximize dynamic range and transparency.

(Beethoven 9 as re-imagined by Mahler, masterfully conducted by Gerhard Samuel)

In and around Beethoven’s own lifetime, arrangements of his works by those close to him were commonplace. Thus we have a version of his Second Symphony (among his most popular works during his lifetime) for piano trio- a version attributed to Beethoven himself, although there is doubt as to its authenticity. Also believed to be by Beethoven is a chamber version of the Fourth Piano Concerto (quintet versions of the other concertos by other arrangers also exist). Beethoven arranged his Piano Sonata in F major, opus 14 no. 1, for string quartet, but this arrangement is still often omitted from many distinguished ensembles Beethoven Quartet “cycles.” Beethoven’s pupil and friend Czerny arranged the Kreutzer Sonata (originally for Violin and Piano) for Cello and Piano, and there are also arrangements of the Horn Sonata for Cello and Piano and another adaption of the Kreutzer Sonata for string quintet.

(Why don’t all string quartets play this piece?)

In most cases, as with Mahler and Mozart, the reasons for these arrangements had to do with a mixture of audience building, artistic advocacy and economics. Brahms’s most commercially successful works were his Hungarian Dances, which we know today primarily as orchestral pieces, but they were originally piano works, and Brahms himself only orchestrated three of them, no’s 1, 3 and 10. Even the ubiquitous no. 5 was arranged by the otherwise forgotten Max Schmeling. However, more eminent artists than Schmeling (whose work on no’s 5-7 is pretty impeccable) contributed to project of orchestrating these seminal works, notably Antonín Dvořák and Hans Gál (of course, until a few years ago, nobody knew what a great composer Gál was. Will we find forgotten masterworks by Erwin Stein or Max Schmelling someday?). More recently, conductor and composer Ivan Fischer has prepared his own, very colourful but considerably more interventionist, version of the entire cycle of dances.

(Ivan Fischer conducting one of his tamer Hungarian Dance transcriptions. Visit the Digital Concert Hall to see what happens when he unleashes the cimbalom)

An interventionist approach to orchestrating another composer’s work can yield fascinating results, as in Mahler’s wonderful re-orchestration of Beethoven 9, Webern’s orchestration of the Bach Ricercar from the Musical Offering, and Schoenberg’s whimsical chamber ensemble take on Johann Strauss Jr’s Emperor Waltz. Where Schmeling, Gál and Dvořák chose to try to keep their orchestrations of Brahms sounding as much like the master as possible, Schönberg threw caution to the wind in his semi-halucinogenic and totally over-the-top orchestration of Brahms’s Piano Quartet in G minor: a work of musical marmite if ever there was one. I can’t stand it (as written about here), but Brahmsians as wise and perceptive as Malcolm MacDonald love it. To me, Schönberg fails to see the point at which his instrumental interventions begin to seriously detract from Brahms’s musical choices. This is a miscalculation he shares with another of my heroes, Shostakovich, whose re-orchestration of the Schumann Cello Concerto stands as one of music history’s all time top 5 own goals. When I set out to make my own orchestration of the G minor’s twin brother in A major, I vowed to stay on the Gál/ Dvořák path, but in the end, what comes across is unavoidably imbued with my own musical personality.

(Listen to it in all its vulgar, twerking glory- Schoenberg’s unique, we hope, take on Brahms’ Piano Quartet in G minor)

Mahler’s efforts on behalf of Beethoven’s Opus 95 don’t seem to have done much to make the piece a hit- it remains once of LvB’s most severe and intense pieces, and will never be a choice for those classical music fans who like their music toothless and tame. Note that I chose to arrange Brahms’s A Major Piano Quartet, one the Cinderellas of his chamber music output, and not the far better known Piano Quintet in F minor, which needs neither further advocacy nor another version. Brahms began the work as a cello quintet, then transcribed it as a Sonata for Two Pianos. When he reworked the piece as a Piano Quintet, he destroyed the cello quintet version (he kept the version as as Sonata for Two Pianos), but that has since been re-constructed, as has the nonet version of his Serenade in D major, which he also discarded after re-orchestrating the piece for symphony orchestra.

(A lovingly-done reconstruction of the nonet version of Brahms’ Serenade in D major by Alan Boustead, played the Orchestra of the Swan and KW. Echt Brahms? Maybe not, but a fascinating window into how the final version came to be, and a joy to play in this form, buy it here)

On the other hand, if you were any composer, living or dead, with a forgotten work to bring to fame, who would you ask to orchestrate it but Maurice Ravel. In addition to his sterling work on behalf of Debussy, he made Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition into one of the most famous pieces ever written. Without his efforts, the original piano work would likely have sat in obscurity for many more years. Now, it is not only a mainstay of pianists everywhere, we have a surfeit of other orchestrations of Pictures to choose from. Leonard Slatkin does a fantastic version of the piece in which each movement is by a different arranger (none of them Ravel), culminating in Henry Wood’s absolutely bonkers finale (I believe he continues to vary the selection even now).

(Leonard Slatkin’s pick-and-mix Pictures, or is the Pick-and-mixtures at an Exhibtion)

Economics have played a huge role in the kind of arrangements we see of great works. In the relatively rich times of fin de siècle Vienna, Mahler was fond of bigging up the works of previous generations. A generation later, in a Europe ravaged by war and depression, Mahler’s disciples, including Schönberg, found themselves shrinking Mahler’s orchestra down to ensembles of less than twenty players with hugely successful results. Among Schönberg’s most interesting re-orchestrations are those of his own music. Having written Verlkarte Nacht as a string sextet, he later expanded it for large string orchestra and, along the way, made many interesting and subtle changes, particularly in tempi. He did the same thing with his Second String Quartet- the rarely played version he made for string orchestra is really sensational and very different from the original. Later in his career, he expanded his First Chamber Symphony (originally for 15 instrument chamber ensemble) for an enormous orchestra- something which has confused concert goers ever since who can’t seem to reconcile the title with the enormous forces on stage. In leaner times, Schönberg’s friend and student, Anton Webern, arranged the same piece twice- once for piano quintet and once for violin, flute, clarinet, cello, and piano, while Berg arranged it for two pianos. That’s five different authorised versions of the piece, for forces ranging between 2 and 100 players. Eduard Steuermann, a Schönberg protege, re-arranged Verklarte Nacht for piano trio. In our own, worryingly similar times, conductors and composers have again begun coming up with reductions of works by Mahler and other late-Romantics. It’s all part of the ebb and flow of music history- a facet of that history which many writers seem quick to forget.

(Mahler for lean times- one on a part songs orchestrated by Schoenberg)

When Trevor Pinnock recorded Anthony Payne’s reduction of Bruckner 2, one of the major music magazines (I honestly can’t remember which one) said this was the first time such a project had been done, completely overlooking the arrangement of Bruckner 7 done for Schönberg’s Society for Private Performances by Erwin Stein, Hanns Eisler, and Karl Rankl in 1921. It’s been well recorded a few times, but when I programmed it with the Rose City Chamber Orchestra in 2006, the idiots at the publishers sent the full Bruckner 7 parts instead, so we had to cancel the performance.

https://youtu.be/ClJ3Zkcl2HI

(These guys managed to get the publishers to send them the right parts. Jealous!)

String quartets make a particularly appealing target for those with an itch to orchestrate. Rudolf Barshai followed Mahler’s example in arranging Shostakovich’s Eighth and Tenth string quartets for string orchestra (although Barshai always envisioned a chamber ensemble, where Mahler intended something far more massive). Encouraged by Shostakovich’s positive response, he went on to make more interventionist arrangements of the Third and Fourth quartets which would eventually include woodwinds, brass and percussion. Inspired in part by both Mahler and Barhsai, I made an arrangement in 1999 of Viktor Ullmann’s then almost completely unknown Third String Quartet which I’ve been thrilled to see some of my colleagues take up.

(The English Chamber Orchestra recording my orchestration of Ullmann’s Third String Quartet. Damn those cats can play. ( CD available here, score and parts here))

I hope that all this history shows us that as a moral proposition, orchestrations and arrangements are completely neutral. An arrangement or orchestration is as worthwhile as it is effective, engaging and illuminating. An arrangement that respects the original is always welcome, whether it be as self-effacing as Gál’s treatments of Brahms or as wacky as Elgar’s treatment of Bach. In the case of our Elgar Pilgrimage premieres, my choice in programming these versions was easy. Don did me the great, great honour of inviting me to record Sea Pictures after seeing me do Elgar 1 in Wisconsin (in spite of the fact he thought I took the introduction too slowly).

(Slow, but not too slow…)

Recording his sensational new version of this great song cycle in Abbey Road, in the very studio that Elgar opened and in which Janet Baker and Barbirolli made their famous recording thirty years later, was a career highlight. As the Jerusalem setting shows us, Elgar’s orchestral fingerprints are as distinctive as any composer in music history- he’s a gift to every music student ever to have to survive “drop the needle” tests in music history class.

(The making of Sea Pictures as re-imagined by Donald Fraser)

Don’s Sea Pictures sounds like vintage Elgar (he’s modelled the string writing on Elgar’s Introduction and Allegro), while bringing to the fore musical details, especially relationships between the original vocal part and countermelodies in the orchestra, that are not as apparent in the original. With that experience under my belt, there was no doubt in my mind that we had to find a way to do the Piano Quintet arrangement when Don told me about it. He’d been inspired by Alice Elgar’s description of the early material of the Quintet as the basis of a “War Symphony.”

Before the premiere in 2015, we organised a performance of the original version of the Elgar Quintet alongside the Brahms Piano Quartet in G minor which Schönberg so famously mauled, then came back the next day to hear the piece in an entirely different way, as the symphony it might well have been.

In recent years, I’ve noted that some colleagues take a somewhat disdainful attitude to the art of orchestration. History tells us that these folks would not have found much sympathy for their point of view with Beethoven, Brahms, Bach, Mozart, Elgar, Schoenberg, David Matthews, John McCabe, Ravel, Rimsky-Korsakov…..

(Former ESO composer-in-association, John McCabe discusses the transformation of his String Sextet, Pilgrim, into a work for double string orchestra)

UPDATED January 2019

Since this post was written, I’ve completed a number of interesting (at least to me!) arrangements. The most ambitious of these was my orchestration of Brahms’ Piano Quartet in A Major. We premiered and recorded that orchestration with the English Symphony Orchestra in November 2019.

Here’s an interview about the arrangement with me and producer Phil Rowlands

You can read more about the arrangement process and backstory here.

There’s an overview of press reaction to the project and a way to buy the CD here.

There’s a trailer for the project here, too

Great to see you in good old Mills Hall, Ken!

Cheers, Brian! Many fond memories of that place

Great piece Ken

I do believe that Menuhin was President of the Elgar Society when he asked for the string arrangements from me! I’m sure he would approve

Don’t forget beethoven’s own arrangement of the any Irish and Scottish flock songs as well as his fantastical arrangement of the Violin Concerto for piano and Orch. with the amazing cadenza with piano and timpani ðŸ‘

I don’t understand why some people just hate arrangements. It’s not as if it’s instead of the original, which still exists. Fine words. The only less than enthusiastic review we had for the Elgar/D. Matthews Quartet CD was from the Elgar Society!

I’ve always enjoyed the process of orchestration and arrangement, ever since I started doing marimba quartet arrangements of classical works for my undergraduate percussion ensemble. I find it to be a therapeutic and thorough method of understanding and honoring the original work. As to the question of morality, well, as far as I’m concerned, the more music there is in the world, the better.