I learned this evening that Gerhard Samuel, composer, conductor, violinist and teacher, has passed away at the age of 83. Gerhard is a man I am very proud to call my teacher and my friend.

Gerhard had a career and a life that would have made a fine novel, and he was very much a man of his time- the quintessential post-war musician whose career would span an earlier career in collaboration with the giants of 20th c. composition and performance to a period of immense productivity in the heart of 60’s experimentation as music director of one of the hippest orchestras ever, the Oakland Symphony, to a long and distinguished record as a conducting teacher and orchestral pedagogue at the University of Cincinnati.

Gerhard’s father was a doctor who could have made a fine career as a painter (he was a colleague and friend of the Blaue Reiter school of painters, and his works and those of some of his Blaue Reiter colleagues hung in Gerhard’s apartment until his death), and his mother was a brilliant woman who Gerhard credited for the basis of his education. Jewish and gay, Gerhard’s family’s escape from Nazi Germany on the last train to let allow Jews out of the country could have made a fine film. When he finally told me the story over coffee after his retirement I don’t think I breathed for an hour.

Gerhard went on to study at Eastman and Yale, where his mentor was Paul Hindemith, and then studied conducting at Tanglewood with Serge Koussevitzky. Gerhard thought Koussevitzky was a genius as a conductor but a terrible, terrible teacher, but his time at Tanglewood also gave him some great opportunities to study composition and to get to know the other important young composers of his time. During these summers, he and Copland became close (he was characteristically discreet when I asked if they dated) and Gerhard would go on to give the European premiere of the Short Symphony.

After graduation, Gerhard moved to Paris and had a busy period organizing new music concerts, before opportunity called him back to America. Through his Tanlgewood contacts, Gerhard had been engaged to do a piano reduction of Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms, and Stravinsky was thrilled with Gerhard’s work. When Antal Dorati, then Music Director of the Minneapolis Symphony, complained to Stravinsky over dinner that he couldn’t find a decent assistant, Stravinsky strongly recommended Gerhard.

Gerhard not only became Dorati’s assistant, but also the associate concertmaster of the orchestra. Gerhard’s gift for innovation quickly made itself felt. Over the course of his career Gerhard started orchestras, festivals, contemporary music series and countless other endeavors, but at Minneapolis he had the rather brilliant idea of pitching the idea of a Sunday evening operetta series with the orchestra. The board loved the idea, but Dorati hated it “If you let Samuel cheapen this institution with his Gilbert and Sullivan and Strauss, then I quit!” he thundered. Well, the board took Garry’s idea and ran with it and, somehow, Dorati’s resignation letter never showed up. The series became a huge money maker for the orchestra, with semi staged performances of all manner of light operas selling out week after week for many years.

During this time, Gerhard’s parallel work as a violinist in the orchestra gave him the chance to work with many of the great names of 20th c. conducting. It was no surprise to hear that Gerhard had played under the conductors he had, but his takes on them were constantly surprising. Gerhard himself was an old-school conductor in the literalist tradition of Weingartner and Toscanini, but it was interesting that some of the conductors whose personality and approach seemed most similar to his were the ones he least enjoyed playing for. He loathed playing for Szell- he said Szell would beat every possible horse to death in rehearsal until every drop of flexibility and spontaneity had been beaten out of the orchestra, but that Szell would then get “musical” and inspired in the concerts and disaster would ensue. On the other hand, Gary loved working with Stokowski, whose cavalier attitude to the score was so far from Gerhard’s more reverent approach. Gerhard said Stoki had the most perfect technique ever, and simply didn’t need to rehearse. “Szell would come in and grind us down in four grueling rehearsals then go berserk in the concert and cause a train-wreck in a Brahms symphony. Stoki could do the same piece on 20 minutes rehearsal- just go over the transitions and a few details, and the concerts were transcendent.”

Then in 1959, Gerhard became the Music Director of the Oakland Symphony. Gerhard was shrewd- yes, he loved to do the music of his time, but he also loved his operetta. He was always careful not to simply do what he wanted, but to do what was right for the orchestra. In Oakland, however, he found an orchestra where the opportunities available to the organization were ideally suited to his talents and interests. What other conductor would host an LSD trip in his garden with Ned Rorem? At this time, the San Francisco Symphony was the antithesis of the innovative group we know today- it was one of the stodgiest and most conservative orchestras in the country, and profoundly out of touch with the mood of the city and the region. Gerhard offered the Bay area of the 1960’s an orchestra that was perfectly suited to capitalize on the progressive trends of the day. The orchestra’s programs were consistently among the most progressive in the country, with countless premieres.

Also during this time, Gerhard co-founded the Cabrillo Music Festival with Lou Harrison (his successor include Carlos Chavez, Dennis Russel Davies, John Adams and now Marin Alsop, who is still there, of course) and the Oakland Chamber Orchestra. During these years he was at the forefront of presenting early performances of works by major composers as diverse as Lou Harrison (a close friend for many years), Penderecki, Lutoslawski, Terry Riley and even older composers like Milhaud. The Oakland Symphony was the “in” orchestra in San Francisco- even Peanuts creator Charles Shultz was a big fan and drew a cartoon which became a billboard all over the city. “You know, Snoopy, I really like the Oakland Symphony,” said Charlie Brown. “Yeah, they’re my kind of orchestra,” answered Snoopy. The cartoon hung in Gary’s apartment in Seattle at the time of his death.

Gerhard’s departure from Oakland was somewhat painful for all concerned, but looking back, his time with the orchestra was a golden age for him, the orchestra and the city. The orchestra never again would be so popular, and finally folded in the 1980’s when it was only a shadow of its former self.

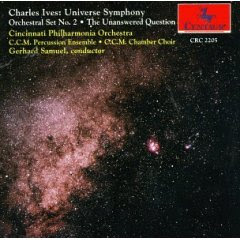

After a brief stint as resident conductor of the LA Philharmonic under Zubin Mehta, Gerhard was invited by La Salle Quartet founder Walter Levine to join the faculty of the University of Cincinnati College- Conservatory of Music in 1976. In 21 years at CCM, Gerhard built one of the best orchestral training programs in the world, developed the CCM Contemporary Music Ensemble into a virtuoso group and led a conducting training program rated by US News as best in the country at the time of his retirement in 1997.

The Philharmonia made groundbreaking recordings of works like Hans Rott’s Symphony, a work that has now firmly entered the repertoire on the strength of Gerhard’s recording and performance at the 1989 Mahler Festival. Gerhard’s recording of Larry Austin’s realization of Ives’ Universe Symphony drew raves from the NY Times, and his first recording of Mahler’s orchestration of Beethoven 9 remains a benchmark.

His final concerts with the orchestra from Cincinnati were on a tour of Portugal organized as part of the 100 Days Festival in Lisbon. Gerhard conducted astounding, deeply moving performances of Bruckner’s Symphonic Prelude, Mahler’s Lieder eines fahrenden gesellen and Rott’s Symphony on one program and the Mozart Requiem paired with his own Requiem for Survivors on the other. Typical of Gerhard’s unparalleled generosity, he let Jindong Cai conduct his piece and let Jindong and I both do most of the conducting on the Contemporary Music Ensemble concert that opened the tour. I’ll always remember sitting in a line of chairs with all the other conducting students during the Rott in shared stupefaction at the performance he drew out of the band that night- Gerhard wasn’t always on and could sometimes make the mistake of not spending enough time with a piece he’d done before, but at his best, he was the best. The Mozart and Rott performances on that tour were worthy summations of his incredible life as a performer.

Through all of these years, Gerhard composed prolifically and powerfully, and many of his works are recorded. There is the Requiem for Survivors- his “hit,” which has a touch of Schnittke-like poly-stylism with its crafty interweaving of the Lacrimosa theme from the Mozart Requiem with jazz and 12 tone music, but there are also chamber pieces, a very good solo violin piece written for Henry Myer’s performance at the Holocaust Memorial’s dedication, songs and even a concerto for steel band. I’m proud to say that I commissioned and premiered one of his very last pieces- Intense Memories, an unusual direct and personal examination of the scars of his years in Nazi Germany. At the time of his death, he was working on an opera based on the Siegmund myth, Blood of the Walsungs, which he apparently just finished.

I’ll have more thoughts on his remarkable life and career and on our friendship in the days to come, but in the mean time here are some tributes worth reading.

Joshua Kosman- San Francisco Chronicle

Melinda Bargregn- Seattle Times

Charles Shere- The Eastside View

Janelle Gelfanrd- Cincinnati Enquirer

Thanks for this tribute, Ken. He seems to have abeen an influence to many fine musicians.

I didn’t know Mr. Samuel, but I did hear a CD of some very good string quartets of his.

Hi Steve-

Great to hear from you- it’s been a while! Hope all is well in your corner.

Check out the podcast on the next post- it’s longish (about 30 mins) but has some great performances of his and other’s music.

K

Oh no! I just saw this. I grew to be very fond of Gerhard over the years at CCM- particularly during the Portugal tour. His rather crusty exterior often hid the kinder, gentler man inside. This brought back a lot of memories for me.

Thank you for writing this, Ken.

~Sheridan

I just received notice of Gerhard’s passing. We were on vacation and were out of touch when he died. I first met Gerhard when I was a MM student at UC-CCM in 1976. I was in the chorus for the opera production of Elixer of Love. It was a full rehearsal and everyone was on stage. At one point, he stopped the rehearsal and pointed his baton at me and said, “You!” I pointed to myself and looked around. He said, “Yes, you! You’re loud and your late!” My friends later asked me what did I think of his small tirade, and I said, “Well, he was right.” I promise I was never too loud or late again!

Some years later, I had a stint as secretary to the Ensembles and Conducting Division at CCM. He was one of seventeen professors that I took care of. It was during this time when I was introduced to the private, gentler side of the Maestro that students (singers especially!) often missed. I had gotten the department a laser printer (the second one in the school — second to the dean’s office). I was showing it to Gerhard — how the paper went in, how the machine hummed, how it spit it out, and how great it looked, much better than anything the old daisy-wheel printer had made. Gerhard’s comment, after much careful observation, was (under his breath), “What a world we live in where we can make such wonderful things and people are killing each other for food!” It was at this point I decided to make sure he laughed every day.

After I left, he started calling me up, about every 4-6 months, asking if I’d become his private secretary. I had a new baby at the time and told him no, I was too busy. But he kept it up till finally I said yes. I remember the conversation on the phone. I asked, “What is it exactly you want me to do?” After a long pause, he said, “Why, straighten out my life!” I chuckled and said, “How bout we start with your checkbook?” He agreed and we became a part of each other’s lives for about five years, up to the time he left Cincinnati for Seattle.

I fell in love with this wonderful man. What a teddy bear he was! And such a talent. But his strongest virtue was his love and dedication to his students. I have now come full circle, teaching voice at CCM in the Preparatory Department. Gerhard is my inspiration to become the best teacher I can. I only hope I’m half the teacher he was.

He will be missed.

Wow Ken! This is an amazing blog on a dear and beloved teacher. Even a year since his death, I am still thinking about that remarkable man, and I fortunately stumbled across your wonderful memories.

Today, I still hear Gerhard in my head as I approach the podium. He was a strict interpreter of the score (“Do what the composer writes”). As a snooty-nosed 20-something beginning conductor, Gerhard could easily shatter my fragile ego at the podium (I remember him interrupting rehearsals by clapping and shouting “COME ON!”). Yet, it soon became apparent to me that he cared . . . not just cared, but LOVED the score and he wanted it to be done right. I learned to question myself always, and know as much as I could; study as much as I could. He instilled a dignity and work-ethic that is the only way a conductor should approach the most humbling task of working with an orchestra. Even today, I always remember Gerhard’s admonition to question myself FIRST if something doesn’t work in a rehearsal.

Like you, I was amazed when I spoke with Gerhard about his contact with the legendary musicians. I remember studying a score by Rachmaninoff with him once. Like you, I thought he would have been rather critical of a composer who held so tenaciously to romanticism in a modern age. I was surprised by his enthusiasm and deep understanding of a musical style seemingly foreign to Gerhard’s in a lesson. Then I asked him (naively!) if he had ever met Rachmaninoff. He related a story to me about assisting a photographer in New York when he was a teenager. Rachmaninoff came to this studio, and to Gerhard’s surprise, Rachmaninoff was talkative and happy . . . not at all how he imagined him.

There were so many stories he shared with us like this! Wow! There were stories about Hindemith, Stravinsky (and Craft), Stokowski, Dorati, Bernstein (not his favorite), and so many others. Also the frightful stories of escaping Nazi Germany as you mentioned. I remember saying that Albert Einstein’s family actually sponsored his family to come to America. We were all so lucky to study with Gerhard. At certain times during the year, he would invite all his students to eat Chinese food (a personal favorite of his). He was forever generous with his time and his musical knowledge.

His music lives on in all of us!

Christopher Stanichar

Director of Orchestras at Augustana College

Music Director of South Dakota Symphony Youth Orchestra

Christopher-

So good to hear from you! Thanks so much for taking the time to share your memories of him- great stories. I hope all’s well there!

K

Mr.Woods:Gerhard ( Garry ) Samuel was a close friend of mine, beginning with concerts I attended of the Oakland Symphony in the early ’60’s. Since we had been out of touch for several years, I went on line to find a contact for him, ( he was always hard to reach by phone in Seattle )and was shocked to discover he had passed away. He was a wonderful, gentle and kind human being.

In 1968, and by fluke, I entered his charmed circle at the Cabrillo Music Festival in Aptos, California in this manner.

In 1967, I had escaped the Haight-Asbury after the April 15th Mobilization Protest Parade, and returned to my familie’s beach cabin at Yachats, Oregon ( a place Garry would later visit to compose ), and while sorting out the haze my life had been in San Francisco, came across a Nonesuch Recording of the Ives First Piano Sonata, with Noel Lee. I was moved enough to write a letter to the pianist, in care of Nonesuch, and it was finally forwarded to his address in Paris. In short, I received a reply from Noel and he thanked me for my comments, and included an invitation to meet him, as he was performing at the Cabrillo Festival, playing a Mozart Concerto ( K.467 ) under the direction of his good friend Garry Samuel.

So, it was there I finally met Garry, bobbing in the surf, at a gated residence, renting a lovely house, filled with lovely and handsome boys he loved to collect.

I have many fond memories to share and they would fill a small novella, if I knew who to send them to.( Lunch with Lou Harrison on the hill, and hilarious episodes involving events that shocked the acting Director of the Festival, all because of an unlocked front door!)

At any rate, I believe that was the last year of the festival!

One of Gary’s works was premiered at that festival, and I remember how outraged Garry became when a critic ( down from San Francisco ) commented on his piece, saying, “Well, there’s much to be said for whole and half notes!”

Please feel free to contact me if someone is putting together a book on Gary. I thank you for your tribute to Garry and filling me with pleasant memories. Robert

Thanks for this Ken. Samuel visited Peabody when I was a student of Prausnitz. They were long-time freinds.

Gerhard taught us so much, and with love. RIP