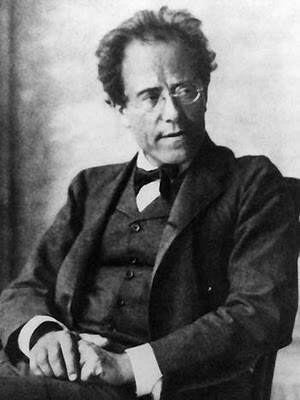

As we approach the 100th Anniversary of Mahler’s death (which took place on 18 May, 1911), we thought it might be interesting to offer a few essays or meditations on why Mahler’s music speaks to us today as it does. First up, regular Vftp contributor Peter Davison puts forth his own answer to Norman Lebrecht’s fundamental question about the composer. Do you have your own answer? A meditation on Mahler you would like to share? Guest submissions are welcome at info@kennethwoods.net, you can leave a comment below, or we can link to your blog or website.

Why Mahler?

In his thought-provoking recent book, from which my article borrows its title, the music critic and renowned Mahlerian, Norman Lebrecht, asks this short and simple question. He goes on to offer a convincing, highly personal sequence of answers. Mahler, he suggests, is a soul-friend at those moments in life when you really need one. He adds that Mahler puts us in a critical frame of mind, compelling listeners to seek the truth behind appearances. Lebrecht is right, of course, and not a lot more needs or can be said. Nevertheless, as the precise day of the Mahler centenary approaches, I could not resist trying to answer the “why Mahler” question for myself.

The century since 18 May 1911, when Gustav Mahler died during a ferocious thunderstorm, has been a troubled period for European civilisation. By contrast, well over a hundred years before this date, The Enlightenment had boldly proclaimed that reason would lead to a harmonious human society. But that confidence gradually eroded as the full consequences of the cult of rationalism and science became apparent. Religious belief went into decline, replaced by equally divisive political ideologies. Our sense of being part of Nature was lost along with our reverence for its divine origins. Technological advances brought many benefits, but led to the exhaustive exploitation of natural resources and widespread industrial pollution. Vast new machines contributed greatly to the carnage of two World Wars, including the holocaust. Today, to fill the void, our Western culture clings desperately to the empty fantasies of consumerism; delusions fuelled by the promise of instant gratification and sold to us by an all-devouring twenty-four hour media. We live in perpetual fear too; fear of environmental catastrophe, of terrorism, over-population and economic meltdown. Indeed, the last century has been a sorry tale of cultural decline, destructive values and soullessness. Worse – we have happily exported this spiritual poverty to every corner of the globe. Modernity’s objectifying forces have crushed indigenous cultures and oppressed the individual, until we have all but lost touch with our deeper human needs. Obviously, it is not all bad everywhere, but we hardly dare to imagine a brighter future. Mostly we aim to muddle through or just forget.

So – why Mahler? In this, I confess, rather gloomy context, Mahler offers hope. He shows us that the lone voice or marginal figure can make a difference. Confronted by many social obstacles, he held fast to his creative mission, believing in the power of music to elevate and transform. His vision was born from and expressed through music, imbuing it with profound moral purpose, making it the true language of the soul in a secular age. His life was heroic; sometimes triumphant, sometimes merely defiant. He was occasionally defeated, exposed as flawed and egocentric. But the failures made him more human, deepening his sympathy for the hapless drummer boys and abandoned lovers who people his imaginative world. Mahler laughed and wept in adversity, mourned and celebrated human existence in equal measure. His music announces calamity, but only once concedes defeat. He was a prophet of doom with a vision of transcendence and, as such, he is a composer for our times.

Mahler lived to create and spared himself nothing to bring his art into the world. Despite his early death, his life and work were oddly complete. His way of dying was not martyrdom, as Schoenberg felt, but the fulfilment of a destiny. His life and death provide a rich accompanying narrative to the music; like a layer of myth which ensures we keep listening and discussing his story. He was not a modern Messiah, because Mahler’s story is our own, for now we are all outsiders, made exiles in our own land. Mahler articulates our own messy struggle for meaning in an incoherent world, as we strive, like him, to release spiritual forces in ourselves which may yet rescue us from disaster.

Mahler never pretended his path was easy. He often described himself as Jacob wrestling with the angel, insisting “I will not let you go, till you bless me”. Heaven is not easily brought down to Earth, but Mahler grappled with the angels to give us those many incomparable blessings found in his music. What is more, it is an inspirational fact that a provincial boy, son a Jewish inn-keeper, became not only Director of the Opera in anti-Semitic Vienna, but one of the greatest musicians of his or any age. So, after a hundred years, we should take a moment to share in the hope and the beauty which Gustav Mahler brought into this turbulent world. He reminds us that, even if our culture has badly lost its way, we should never abandon the possibility of something better.

Norman Lebrecht’s Why Mahler? How One Man and Ten Symphonies Changed the World is published by Faber and Faber, London 2010

Peter Davison’s Wrestling with Angels, the official commemorative booklet for the Mahler in Manchester 2010 concert series, can still be bought from the shop at Manchester’s Bridgewater Hall.

Well put Peter. In a soul-less society, GM’s music speaks deeply to the soul and people respond. Also, Mahler is that colossal genius who experienced failure in love, recognition and health – we love our gods to experience diappointment. In that sense, Mahler was one of Wotan’s own.

BW

Indeed a very erudite answer to Lebrecht’s question.

My own humble musings on Lebrecht’s book: http://bit.ly/mNBGYI

Best regards,

Alan Yu

@David Galvani

Thanks David!

I had never thought of Mahler as a Wotan-figure, but there is something in it. Central to Mahler is that tension between the divine and the human. He was also a great Wagnerian conductor.

Wotan was also in some sense an exile wandering ceaselessly – a god whose left hand did not know what his right was doing. That’s one fr the theologians to ponder, but you meet plenty of people like that.

Peter

@Alan Yu

I enjoyed your review and would agree with much of it. Norman Lebrecht can be quite deliberately provocative and he has, at times, a very subjective view. The hints of cantankerousness he shares with Mahler, who cannot have been the easiest colleague or husband. Mahler can often be a mirror of our own pre-occupations so any book about him will tell us as much about the author as the composer. I always fear that if I met Mahler, I might not have liked him very much. He would have been an intimidating presence.

Peter