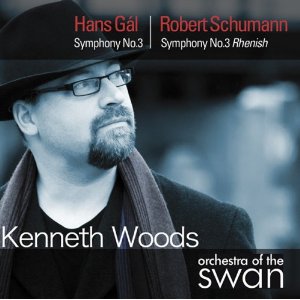

Classical CD Reviews has up a new review by Gavin Dixon of the Orchestra of the Swan recording of Gal and Schumann 3rd Symphonies on Avie records.

Each successive release of Hans Gál’s orchestral music fits another piece into the jigsaw, and yet his musical persona remains as difficult as ever to define. This Third and final symphony [correction, there is a Fourth, see postscript] was written in 1951-2. It is complex but conservative, modestly-scaled but expansive in scope, rigorously Austro-German but also rule-breaking at every turn. There is a curious dichotomy between the sophistication of the orchestral textures and the staid harmonic language, creating a listening experience that is always interesting despite lacking emotional turbulence.

It is tempting to hear British influence in this music, written by an Austrian émigré living in Edinburgh. Elgar in particular is a voice that seems to be hidden somewhere behind many of the textures. But no, I think it is rather the case that Elgar and his successors were writing in a style that was heavily influenced Brahms and his Viennese contemporaries, as was Gál, whatever country he happened to reside in at the time.

The Third Symphony is written for a relatively small ensemble, but it makes the most of the limited orchestral resources, giving every player a real workout. The young players of the Orchestra of the Swan respond well to the many challenges the score presents. One or two of them, I’m thinking of the oboe, flute, clarinet and horn soloists in particular, seem to be playing exposed lines almost throughout, and all rise to the challenge magnificently.

There is an endearing sense of nativity to the music, and I can’t decide if this is the result of the composition or the performance. Gál’s post-Brahmsian orchestration and counterpoint have a certain matter-of-fact quality, especially in the absence of any meaningful transient dissonance, which Kenneth Woods amplifies by maintaining fairly strict tempos throughout. That’s not to say the performance is in any way rigid, but rather when the score provides opportunities to linger, discipline is always maintained and the performance moves on. The only place where this discipline feels excessive is the opening passage of the second movement. This is marked Andante tranquillo e placido, which surely gives license for a little more indulgence. But then, Woods knows that his woodwind soloists can give him all the emotion the music needs, without him having to pull the tempos around, and they more than repay his trust…..

The coupling of Schumann’s Third may seem like an opportunistic commercial move, but the logic is impeccable. Gál was, after all, the author of a book on Schumann’s orchestral music, and the stylistic legacies are crystal clear…..

The players give an enthusiastic but focussed performance that works best in the inner movements. Here we find some really sensitive ensemble playing and a wonderful elegance of tone from every section. I was particularly impressed by the trombones at the start of the fourth movement. The astronomical register of the alto part here daunts most players, who are happy to be able to get the notes out at all. So to hear it played with this apparent ease and, most importantly, serene elegance is a real pleasure….

Recent Comments