I read this review of a performance of Mahler 1 today:

“Among the rare highlights were the impressively unisono Frère Jacques (played by the basses in tutti with just the right amount of dread)”

Jens F Laurson, reviewing the London Symphony Orchestra playing Mahler 1 with Gergiev in Leipzig this week (I appreciate Laurson’s openness to Gergiev’s flawed approach)

Which reminded me of this:

“However, assigning the new edition of the First Symphony to Sander Wilkens unfortunately proved to be a mistake. His confused arguments in support of the claim that the famous double bass solo at the beginning of the third movement was a solo for the whole group rather than for a single player contradicted the sources and surviving reports of performances under Mahler’s direction, and exposed the Critical Edition to ridicule from all Mahler researchers….”

Reinhold Kubik, editor in chief, New Critical Edition, International Gustav Mahler Society, Vienna

Cambridge Mahler Companion, p 224

Which mercifully contradicts this:

“NOTE ON THE BASS SOLO (3rd mvt., p. 78)

The “solo” instruction for the basses at the beginning of the third movement is a relic that has survived several revisions and has therefore occasioned a misunderstanding. [A] notes “Celli” and “Bässe” before systems 1 and 2 respectively, Bar 3 “Solo (mit Dämpfer)”, pp; Vc. Bar 11 “Tutti (mit Dämpfer)”; [K1] corrects this (autograph) to “1. Kontrabass”, “Dämpfer” added later, and strikes out Vc. Bars 3-11 including the “solo” at Bar 11; [StV1] repeats this version–1 Kb. mit Dämpfer, Vc Bar 11 tutti (system cues continue in the singular as in [EA], except for the timpani). In point of fact, the first edition abandons the system cues identifying the solo (1 Kb.) and prints all the basses in Bars 3-11; this permits only one conclusion, that Mahler was resolved in [EA] to keep this version, whereas the parts merely copied [K1], and in no version passed down to us, including [St1], do they appear to be corrected. The meaning of the “solo” marking which remains in the score thereby changes to a unison section soli”

I’ve gotten great pleasure from my Mahler 1 score as edited by Sander Wilkens, but his reasoning for insisting that solo doesn’t mean solo is ludicrous and not the least bit logical, musical or credible. I’m amazed anyone has ever fallen for it- it just goes to show how blindly we sometimes accept the word of scholars. As Wilkens and Kubik show on this point, or as Kubik and Ratz illustrate in the case of the movement order of the 6th Symphony, a conductor who blindly follows the opinions of the scholar-de-jour is going to be changing his or her interpretation every few years without fully understanding the reasoning. A critical edition should still be challenged and questioned, and when it is wrong, its suggestions should be ignored. In this case, I’m pretty darn sure Mr Wilkens got it wrong and Mr Kubik gets it right.

For a more detailed explanation of why, see Paul Banks’ essay here. Note what he reports about Mahler’s own performances:

“But the most compelling testimony concerns Mahler’s own practice: in his review in the Neues Wiener Tagblatt (20 November 1900) of the first performance of the work in Vienna (i.e. after the publication of the score and parts), Max Kalbeck refers specifically to the use of a single double bass at the opening of the slow movement (I’m most grateful to Donald Mitchell for drawing this review to my attention). To this can be added the fact that in all seven of his recordings of the work, Bruno Walter (who made the piano duet transcription) gives the opening statement of the theme to a solo double bass. All of this provides strong evidence that what was awry here was not the score, but the first edition of the orchestral parts: for once a long-established performing tradition is correct.”

It’s a bass solo!

UPDATE March 2019

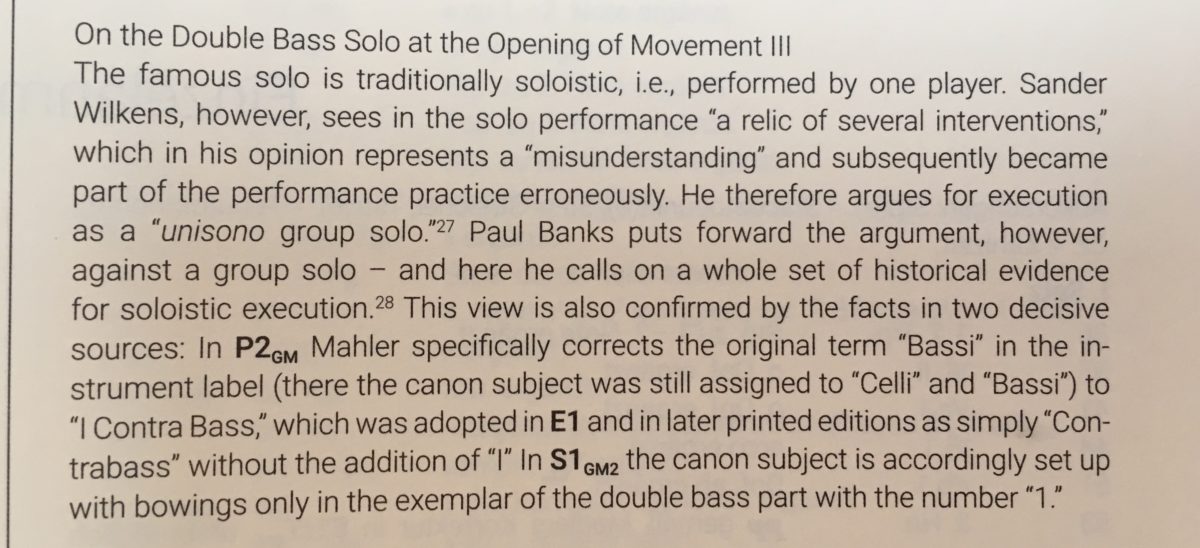

The new Critical Edition from Breitkopf & Härtel has this to say:

You can hear the world premiere of the new Breitkopf edition at Colorado MahlerFest on the 19th of May, 2019. Details are here.

I would agree with you Ken about this. Scholarly research sometimes seems to lead editors into inflated theorisation for its own sake.

I’d add a few other good reasons for keeping this passage solo that are perhaps more musical than theoretical. Firstly the processional here suggests approaching from a distance with a hint of the grotesque. The fear of God which this solo engenders in the player guarantees that it will sound fragile, distant and in no way beautiful. The audience will share a bit of that nervous vulnerability too when listenin, like watching a man on a wobbly bicycle. The impact of this effect is greatly lessened, if the passage is played tutti.

I then wondered if there was another example of a solo string-part beginning a movement in Mahler. There is one; the Second Nachmusik in the Seventh opens with a violin motto marked solo, and solo here means solo.

Of course, where printing errors and inconsistencies exist, it always possible to make an argument one way or another, but there are other sources to take into account, as Ken has said, which can help decide. But, as with the Scherzo-Andante argument, performance tradition is also a factor. If a tradition has stuck, it is often for a good reason, even if it is intuitive and has not been consciously thought out.

Finally, Mahler had a great sense of humour and a penchant for the occasional bullying of weaker orchestral players. He wanted virtuosity in every desk of every section of the orchestra and he liked to expose, humiliate and expel passengers who were not pulling their weight. Pushing the boundaries and testing the technique of individual players were part of what makes the Mahler orchestral sound so special. Placing an exposed double-bass solo in his first symphony seems entirely true to character, and no doubt he enjoyed with a wry smile the anxious altitude sickness of the section leaders who were faced with this solo.

So you’re saying the solo is for the whole section…

It is amazing that there is doubt over an instruction that was written a mere century ago. It is not as if this is 1600s.

Great 7th from RLPO on Thurs, where indeed the violin solo introduced the second Nachtmusik. Final movement convincing although must have seemed strange in 1910.

Good to have all of that rubbish summarized.

Isn’t there also a Haitink/CSO live recording with section basses?

An interesting bit of collateral support (as if it’s needed) for ‘bass solo = solo bass’ can be found in Forsythe’s “Orchestration” [I have only the Dover reprint of the 1935 second edition] where the opening of

the movement is printed, primarily to demonstrate a rare instance of muted timpani, with the comment that the solo [italicized] double-bass is also muted.

@Joel

Hi Joel- I think you are right about the CSO/Haitink. I read a review that said that was the case, but I haven’t heard the disc myself. How could such a great conductor fall for such a load of horse hooey…

@David Galvani

Hi David-

Thanks for the comment. Wish I could have heard the M7- the reviews have been pretty ecstatic.

You would think that such a basic wrong reading could never be taken seriously in a modern society, but we live in a world were everything has become opinion, be it climate science, evolution or performance practice. We’re so anxious to respect the text, that we don’t carefully vet whether the text we’re respecting is really what the composer intended or not!

Hope all is well there. Best to Marco.

Ken

@Peter

Hi Peter. I completely agree with you.

Wilkens seems to be inherently suspicious of the notion that Mahler would write a solo for double bass, and therefore, reads all the evidence through the prism of “how does this prove I was right to be suspicious.” The fact is, the more odd something looks in Mahler, the more likely it is to be right.

Mahler’s bowings are a good example- some of them look insane, until you realize that there is always one particular way to make the most perverse seeming bowing work, and when you find that, you get a real window into how he wanted it played.

In Mahler, perverse is orthodox, weird is typical, and unprecedented innovation is to be expected at all times

@Erik K

Sorry Erik that last sentence could be read two ways – of course I mean section-leaders in general, not at a specific performance. In Mahler anything is possible, but not a fight over who leads the section written into the score.

You can imagine a scenario where the editor of the original edition didn’t believe it was a solo and missed it out, so Mahler asked them to change it, but it i when you change things that the knock-on impacts get forgotten – such as marking orchestral parts and when the tutti section begins.

A better explanation for the inconsistency is surely that the solo title was added at a later stage in the editing by someone who didn’t think through what else might need to be added as a consequence. We’ve all done that when editing or proof-reading. You spot a big omission and forget that by changing “x”, you also have to change “y”.

Hi Peter,

I was actually being a sarcastic dope in reference to the post in general, but I failed pretty miserably. Your comment was perfectly clear. I, in fact, owe you an apology for having to clarify, because your initial point was made succinctly.

I remember having a tough time making sure I had all the string bowings in parts that I was preparing. I would probably embarrass myself if I were trying to edit a major score.

@Erik K

No problem Erik. Tone, especially ironical tone, is hardest to read from written text. Chances are I was having a sense of humour failure at the time I read your reply. Perhaps the person drafting the proofs of Mahler One was a failed double bass player or one of Mahler’s rehearsal victims, then he might have been thinking “in this case solo can’t mean solo”. We are all prone to see and believe what it suits us to see and believe.

I wonder if Wilkens looked at Mahler’s printed score of the symphony which is kept in Southampton University library. Mahler made a few markings on it, if I recall from seeing it many years ago, so perhaps there’s a clue there?

re: M1 & double basses. To me, the question of solo or not is less important than that of character. The ‘absolute-edge-of-the-playable’, the deliberately designed out-of-the-comfort-zone character of that episode in M1 is, I think, the key to Mahler’s deliciously insidious tilting of Frère Jacques. Unfortunately (of sorts), today’s best double bass players are too good to let that part frazzle them in the least. I’ve heard blindfolded renditions that were spot on. Great playing and an impressive achievement, but unfortunately undermining the intention/character of the bit. Playing the thing in tutti seems just like the easiest way of re-introducing a bit of dread and pearls of sweat. Sure, individuals can hide behind each other, but to play it well and in unison probably does make matters a bit more difficult. If I were conducting the work, I’d opt for a more unpopular way of getting the edge back: I would rehearse in tutti, but then decide in concert, spontaneously, and ever-changing, who would be taking that solo that night. That should ratchet up the level of desirable nervous dread!

Cheers & best,

jfl

@Jens F. Laurson

Dear Jens-

Thanks for the comment. I enjoy your blogs a lot. I like your suggestion of picking the soloist- right in the timp vamp- on the night. I might even try it next time I do the piece. Inspired idea, in a cruel way. Love it.

If you really want to see a bass player sweat, pick any of the fiendish solos in the Haydn symphonies. The one in the Farewell is the most famous, but I love the one in 72- it is way more athletic and scary than the Mahler.

All best

Ken

” I might even try it next time I do the piece. Inspired idea, in a cruel way. Love it.”

If and when you do that, I want to see & hear it. :-)

Cheers, jfl

@Jens F. Laurson

I agree with Jens, part of the entire character of that solo is that it’s supposed to be nervously uncomfortable for the soloist, and sadly today it is all to easy for almost all professional principals and recent music college graduates, that they can do it on auto-pilot! I think re-introducing an element of surprise along with an edge-of-your-seat feel could be a great thing!

I once played it with Wrexham Symphony Orchestra (one of Ken’s regular stomping grounds) and I was sitting sub-principal, when unexpectedly some 2 mins before we began the rehearsal of that movement, I was told that the Principal was ill and that I would be required to play it!

I was quite familiar with the piece and the solo having played it as part of a tutti performance with the National Youth Orchestra of Wales some 10 months earlier (yes, this does partly achieve the desired character because everyone is nervous about being the first to shift from one note to the next, and avoiding being that one bass sticking out who’s a little flat or sharper from the rest), and having studied it along with dozens of other predictable audition pieces – but I hadn’t so much as glanced at it for a couple of weeks, and was only halfway through my warm up when that bombshell was dropped on me!

But rather than making a complete hash of it or being overwhelmed by the pressure, I felt I delivered the best performance of it I could – it was a mix of clinical let’s-just-get-through-these-eight-bars-and-avoid-anything-fancy, mixed in with relative accuracy (all that adrenaline had my powers of concentration honed in to the max) – and a sense of the genuine nervousness. It was true to the character that Mahler intended. (It also helped that a rather incompetent timpanist was tuned virtually to and Eb instead of D, and had crotchet beats as steady as the Greek economy…)

That solo is supposed to be uncomfortable, it’s part of its haunting charm. Somehow contemporary conductors and principal bassists need to find a way of getting that across – a bit of surprise might just do the trick!

@Dan Evans

Hi Dan

Great to hear from you. Great comment.

It’s great this discussion has come up again. The character is the passage is extremely important to get right. @Jens F. Laurson surprised me by suggesting that using the section might make it scarier and more difficult than the solo part. I would have thought it would be way less nerve wracking (depending on the section and how much the conductor glares at the basses), but under certain circumstances, a section might feel more pressure than a principal who plays the solo a couple of times every season.

However, the fact is that Mahler did write it as a bass solo, and not as a section solo, and always conducted it as a solo. I absolutely agree it shouldn’t be some big, beefy bel canto showpiece (as one does hear it these days), but I think Mahler was expecting to get the result from artistry and imagination rather than relying on incompetence to do the job. Just like any other soloist, the bass soloist in this piece needs to use his or her entire arsenal of skills to create that eerie mood. Simply making the most robust bass sound and playing in tune won’t cut it. Doing the ‘s that Mahler writes helps. Using vibrato creatively and somewhat sparingly helps. Keeping some reediness in the sound helps- it shouldn’t be too resonant and plush. I’m forever hoping to hear that solo played with jaw dropping artistry and virtuosity in a way that serves the music. I’m sure that would be a better, more musical result than the old “bow-shakes and missed-shift” approach one used to hear 20 years ago, or the “bass-jock” version one often hears today (especially in auditions).

Frankly, what I love about Jens’ suggestion of picking a soloist at random is the element of improvisation and the emphasis on accountability. As you learned, circumstances can change quickly in performance, and it’s always best to be prepared. Condolences on the timpani- although that opening and the beginning of the Beethoven Violin Concerto often go very badly wrong with good timpanists. I think it’s easy for the timpanist to get psyched out. That’s why I think timpanists need tuners, no matter how good their ears- the box doesn’t get nervous!

All best

Ken

Thanks a lot for this post. I particularly enjoyed your comment that “I’m amazed anyone has ever fallen for it- it just goes to show how blindly we sometimes accept the word of scholars.” I’d love for you to comment on the changes made by editor Robert Fiske in his 1981 edition of Schubert’s C-major Quintet, that have indeed been blindly followed not by all but by many performers: 1. construing bar 154 in the first movement as a “first time bar”, e.g. seguing directly from 153 to 155 when moving from exposition to development, and thus omitting the “echo effect” produced by the two explosive chords two bars apart – sure, that effect was never put there intentionally by Schubert! 2. placing the repeat bar in the Scherzo after the second beat of bar 186 and thus abridging the repeat rather than repeating the Scherzo section in toto – sounds awful! and 3. playing the Quintet’s final chord with a forceful accent rather than as a diminuendo – so much more banal! And none of that, of course, is based on scrutiny of Schubert’s manuscripts, since these are lost, or on any corrections he might have done to plates or printed score, since he was long dead when they were published. No, it’s the scholar’s assumption of what Schubert must have intended… I haven’t found any online trace of the scholarly discussion that led Fiske to suggest these changes, and he doesn’t provided the reasons, at least in the preface of my Eulenburg pocket score, just claiming that “two probable errors were being suspected by about 1978-80”. Scholars are great, I love and admire scholarship, but some of them, sometimes, should be hanged, and performers sheepishly following their dictates without thinking on their own (and even less feeling…) should have their knuckles wrapped with their own bows.

I am a double bassist, and the story (which may very well be apocryphal) my teachers and others in the bass community have long told is that it was originally written for the section. Mahler himself changed it to solo because the section couldn’t keep it in tune.

The beauty of the bass section muted is that one gets ( believe it or not )a better balance with the entry of the bassoon. One bass was never expected to have the same force (especially muted) as the bassoon and whilst the idea of a Mahler wanting a struggling bass may be amusing, musically I much prefer the whole section.

Look,

Here is a simple fact to end this discussion:

When August Kalkhof played Mahler 1 with Mahler conducting in New York in 1909, he played it as one bass. SOLO!

First hand years ago from people in the orchestra.

Brian