As someone whose lifelong love affair with the music of Bruckner began at a dinner party where he was described as “Bruckner- yes that’s the one! The worst composer who ever lived!” it’s no wonder I would have a certain curiosity and sympathy towards Havergal Brian’s Gothic Symphony, which made its Proms debut last night at the BBC Proms in London.

I’d made a previous, aborted attempt to get to know the Gothic a few years ago while in the Midwest on what would prove to be one of those gigs you want to forget but can’t. I bought the Marco Polo CD while passing through Chicago, and spent the next week driving around listening to it in 5 minute chunks. It was hard to get much sense of the shape of the piece under those conditions, and I was severely put off by the desperately out of tune singing, but there were definitely some cool bits in it. Once I made my escape from a gig I should never have taken, however, I didn’t want to be reminded, and the disc sat on the shelves until a couple of weeks ago.

The Gothic came back on my radar about a year ago when I found out my wife’s orchestra, the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, would be playing it at this summer’s Proms. I hadn’t figured on coming- I was expecting to be in America this week- but plans changed, and when a ticket came available at the 11th hour, I made my arrangements and headed for London.

What to make of this piece?

I don’t do reviews, but I was so struck by my reaction to the piece live that I feel I have to write about it.

In the hours since the concert, critics have been inspired to some highly creative and witty invective by the piece. Gavin Plumley called it “all gong and no dinner,” and David Nice said at The Arts Desk: “All I can say is that before I sat through nearly two long hours of continuous music last night, I proclaimed that this was exactly the sort of thing the Proms should be trying. Now I’m hanging out the garlic and spraying the air freshener to keep Brian’s other 31 symphonies at bay.”

(Whatever the critical consensus proves to be, the audience went BERSERK. Remember I don’t do reviews, but I can say that I was full of admiration for conductor, singers and players, all of whom turned in a very impressive reading of a piece by a composer who really did seem to think of “idiomatic’ as a dirty word)

And yet, this morning, I found myself drawn to listen to portions again on iPlayer. Why? What to make of this insane piece?

Well, let me tell you what I think it is not.

It is not a symphony. Well, of course, on more than one level, it is a symphony, but I’m happier calling it an anti-Symphony. Calling it a symphony might have been the greatest and shrewdest marketing decision in the history of the genre, putting it out for comparison some of the great monuments of classical music. Getting a mention in the Guinness Book of World Records as the longest symphony, supplanting Mahler 3, and the most massive, supplanting Mahler 8, is the best press you can buy. Unfortunately, while the comparison to Mahler sells tickets, it serves neither listeners nor composers well, setting up expectations that Brian never intended to meet. How funny, considering Brian was, by all accounts, one of the least gifted or interested self-promoters who ever lived.

I had tried to prep a bit with the Slovak CD, but never was able to withstand a complete, uninterrupted listen. The performance is just too rough. Last night, however, the Gothic really struck me as not just the least symphonic symphony I’d ever heard, but possibly the least symphonic piece of music in any genre I’d ever heard (including everything from Wagner’s operas to Radiohead) . It is more of an anti-symphony than Webern’s or Stravinsky’s critiques of the genre.

The whole piece seems like an essay in stasis and discontinuity. On first encounter, there is precious little development, virtually no transition, and almost no architectural sense of form- at least often not one that is articulated for the listener through any sense of direction or arrival. Messiaen’s Turangalila Symphony is often cited as an example of a non-developmental symphony, but Messiaen’s approach to form and motivic development is highly structured and easily heard, it is simply that his basic approach to structure is ritualistic rather than narrative. The structure is still there, and articulated. A quick survey of writings on the piece makes clear the structure is there for much of the Brian (although it seems that even Calum MacDonald struggles to explain the structure of the Te Deum). It just seems that Brian almost wants to disguise the form, to keep the audience unsure.

Where Messiaen creates a sense of paragraph and chapter through the use of iconic interruption and repetition, Brian doesn’t really give us anything to interrupt, and most of his potentially iconic themes seem largely disposable. New ideas appear and disappear with disconcerting frequency. It is, on first encounter, about as far from Beethovenian rigour as you can get.

And what would Beethoven have made of this? It is known that Beethoven had serious doubts about whether he had unleashed something dangerous with his creation of the new hybrid genre of the choral symphony. Just as Mahler’s efforts in the genre would surely have left Beethoven feeling vindicated, had he heard them, so too, Brian’s Gothic would probably have struck Beethoven as his worst nightmares made real.

It would have been more honest to call the piece a Cantata with a great orchestral introduction, but we have what we have.

Another thing it is not is Mahlerian.

[I could be completely wrong about this. Calum MacDonald, who is the expert on Brian, says of the piece: “The work’s basic stylistic premises, as set out in the purely orchestral movements of Part One, are a demonstration of artistic continuity, a logical development from the achievements of Wagner, Bruckner, Strauss, Elgar, Mahler and early Schoenberg”]

It was to Mahler that I heard the piece compared most often in the last couple of weeks- bigger than Mahler, longer than Mahler, a lot like Mahler, but without the tunes. I just don’t hear it. That’s not to say Brian wasn’t influenced by Mahler (and Strauss, to whom the piece was dedicated), it’s just that whatever a Mahler symphony sets out to do, what ever a Mahler symphony does, is, feels like, the Gothic is the opposite. Again, it’s more like an anti-Mahler symphony.

Where Mahler’s music has a tremendous sense of individual voice, Brian’s is an exercise in musical multiple personality disorder. Schnittke has nothing on Brian in the arena of polystyistic mishmash. Where Mahler thinks in terms of arrival and culmination, of dialogue, rhetoric and song, Brian thinks in terms of interruption, negation, stasis and outburst. Mahler sets words with matchless care- Brian admitted while writing the piece that he didn’t know what much of the Latin meant, but it hardly matters. Most of the choral writing just sounds like long-winded amorphous melismas, and when one giant movement is a setting of a single line of text (“Judex crederis esse venturus” or “‘we believe you will come to be our judge”) , the words are, whether by design or necessity, deconstructed to the point that they really are just fodder for the creation of pure choral sound. Yes, Brian’s use of hypercomplex vocal counterpoint over vast orchestral forces possibly reminds us of Mahler 8, but Mahler 8 is one of the most tautly motivically unified pieces in the literature. The Gothic is not. At least it doesn’t, on first encounter, sound like it is.

If I had to invoke another composer for comparison and reference in understanding my reactions the Gothic, Mahler would be about 10,000th on my list. Top of the list?

Berlioz

It was famously said of Berlioz that he was a composer of genius but no talent.

Whether Brian’s music rises to anything like genius is something I’ll need to invest a great deal more time to in order to form an opinion. However, there is certainly a jarring contrast in his music between large stretches that seem either incompetent or simply insane and ones which are profoundly effective, sometimes moving and often disturbing.

If there is one work I would say is in many ways similar to the Gothic, it is the Berlioz Requiem. I was struck enough by the similarities (gargantuan scale, use of off-stage forces, static approach to musical time, etc) that I did a little bit of research on the Brian Society website, and it seems I’m not the only one to notice the parallels (they are not hard to spot). I sure it was more of a model than any of the Mahler symphonies.

At the end of the performance, my friend sat next to me remarked that Brian uses the enormous forces he’s demanded with restraint and understatement bordering on the perverse. How strange to assemble the largest performing forces in history for a symphony without a single climax (there are outbursts, but no climaxes). Every time the listener gets the sense that this is the moment when something really is going to bust loose, Brian abruptly stops. Again and again, I found myself looking longingly at those off stage bands (who played absolutely amazingly all night- dealing with those kinds of spatial challenges are a nightmare for players and conductors, so props to Martyn Brabbins and the players for making that aspect of the piece look easy), wishing they would play something. Brian’s use of the auxiliary bands seems calculated to frustrate and annoy. Again, what could be less symphonic?

In a way, I often experience a similar feeling in the Berlioz Requiem, and to a lesser extent, the Te Deum, which is an even more obvious point of comparison. The best bits are so exciting, but a lot of the piece seems, intentionally, introverted, dreary and static.

Was Havergal Brian critiquing, even deconstructing the Romantic symphony? Was he conscious of undermining our expectations, or was he just a batty and misanthropic amateur with delusions of grandeur? Both? Neither? Somewhere in between?

Some of the choral writing is cruelly difficult. Other parts are just bad- horribly set and difficult in ways that make no sense (that is to say that the difficulties make no sense because they could have been avoided). There were surely options, with the huge forces he had in mind, to distribute the chords and ideas in a way that would have been far more likely to be in tune and together. Is Brian taking Beethoven’s apparent disdain for what is comfortable and natural for the human voice to an almost comical point of exaggeration with a genuine element of sadism in play? Is he reaching for the edge of what massed human voices can achieve? Or did he just need composition lessons?

I remember in my very first class on modern art, our teacher spent quite a lot of time explaining how important it was that Picasso could “really draw.” She said that the fact that his later aesthetic was a choice, and that he could have painted or drawn in any style, informs our understanding of him as being completely in command of what he was trying to say as an artist. What he said wasn’t limited by his ability to say it.

20th c. music and the modernist movement is full of difficult questions about which composers could draw and how well, and ultimately whether it matters. The old line about Berlioz (‘genius but no talent’), is, at best, a ridiculous over-simplification, but there’s no question in my mind that he could possibly have “drawn” with the fluency of a Mendelssohn or a Picasso. At the dawn of the 20th c., Schoenberg was a deeply serious musician who did all he could to ground himself in the Germanic heritage of Beethoven and Brahms of which he was so proud. Could Schoenberg “really draw?” Yes, of course he could (of course, he was also a great painter!), but not with the ease, with the mind boggling effortlessness and fluidity of Gustav Mahler or Richard Strauss. For all his genius, Schoenberg couldn’t play in that league. Did this lack of fluency in part drive him towards finding a new language, a space apart from his hero, where he could create without suffering comparison (not least from his own withering self-examination)? How did it affect him when Alban Berg showed that he really, really could draw, in Schoenberg’s idiom, with a fluency the master couldn’t muster?

In the end, in spite of my attempts to be grown up and listen critically throughout last night, my original estimation from the car stereo several years back came back to me with heightened intensity: there are some cool bits!

But, it’s almost two hours of music with virtually no sense of direction or payoff. Not symphonic.

I started this assessment by trying to articulate what the piece isn’t- not symphonic, not Mahlerian, not what you would expect from such gigantic forces.

I hesitate to try to describe what it is- there are seriously smart people out there who have spent years exploring what Brian’s music is. Go and read Calum MacDonald, as I now shall. All I can offer is first impressions, which come with them the huge caveat that I don’t know the piece well at all.

A lot of the piece is funny, but it is hard to tell if it is witty. The “la-la-la’s” and the jaunty 11-clarinet unison theme are absurd by any measure. In those moments, it’s pretty clear that Brian is in on the joke, but whether it is an angry joke, a dry joke or an insane one is hard to tell. Other moments I was close to laughing out loud, such as some of the ridiculously over-the-top silent-movie-spooky-castle music, replete with mega cliché’d organ writing, it’s harder to tell. Is it parody? Had he run out of ideas, or just had a really bad one? Did Danny Elfman know this piece when he scored Batman? Haydn’s music is funny in large part because he knows the minds of his listeners far better than they do. Brian seems about as alienated from his listeners as one can get.

I think the most useful point made in the excellent programme notes had to do with the piece’s connection to World War I. For me, the most effective music, and some of the music that feels most honest (I know that is a very, very subjective judgement) in the piece is genuinely terrifying. There are moments when you feel like this really is a man who has looked, or is looking, right into the abyss. It’s probably for those moments than I was tempted to give this crazy piece a second thought after the concert ended, when most sensible critics were already coming up with synonyms for “rubbish.” I think it is a War piece.

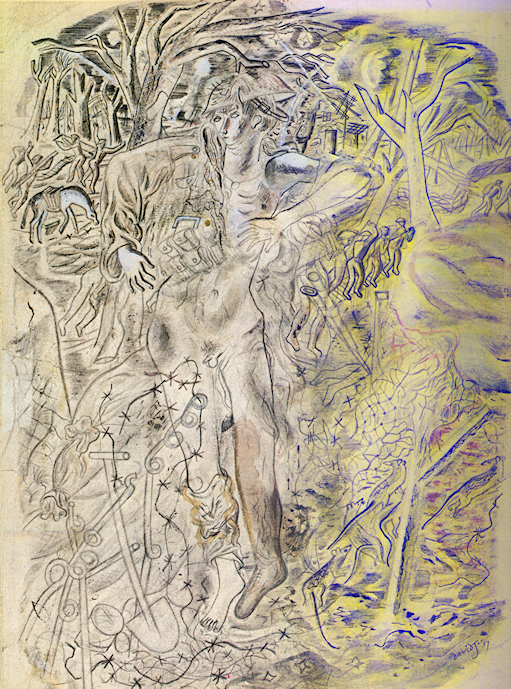

Was Brian haunted by images of the Great War like those from David Jones “In Parenthesis” (frontispiece shown)

It certainly seems like it is an angry piece. It must be, in some ways, the least generous piece of music I’ve heard a long time. It’s not that it’s two-hours of music with no tunes, it’s that the tunes are either trite to the point of parody, or, when genuinely captivating, quickly, well, violated. The piece’s stubborn refusal to engage with or to reward the audience, or to deliver the kind of thrills the giant forces promise strikes me as very anti-social. It is also part of what fascinates me about the work.

And at times, the piece seems to tip over from anger into genuine madness. Brian himself hinted that work on the piece pushed him psychologically to his breaking point: “such happenings must drive others off their mental balance. I have always felt that I, being the only person interested in my work, would discover a solution to all the mysteries about it” It is an insane piece.

It really is amazing that such a vast work can manage to so completely avoid any sense of rhetoric or development. The tunes, such as they are, are mostly set in a modal style that seems to make them sound rather shapeless. Is this intentional? Again and again, it struck me that there was hardly a proper musical phrase, with a preparation that includes a generative thought, a beginning, a direction, a high point and a release in the entire work.

The beginning of the final chorus in Mahler 8, “ Alles Verganliche ist nur ein Gleichnis” is always a bittersweet moment for the listener, because the realization when this beautiful music begins is that it is beginning to end. Mahler makes the piece want to stretch into eternity.

As the performance neared its conclusion last night, Brian’s extremely long last movement inspired thoughts more along the line of begging for mercy (a feeling which I’m sure you, dear readers, are feeling increasingly familiar with as you reach a similar point in this essay). Each time the full forces are used, seemingly for shorter and shorter outbursts each time, there is more of a sense of outrage- “bastard, is that all he’s going to do with all those wonderful brass players!?!?!?”

Through the piece, I’d found myself again and again trying to get to grips with the basic question- did Brian know what he was doing? Is all this discontinuity and negation intentional, or did he just not know how to string a musical sentence together? I was pretty sure he couldn’t “really draw,” but could he draw at all? Was he someone who ended up writing musical nonsense poetry because he was an angry social critic who didn’t give a damn whether anyone enjoyed a note of his music, or was he just a crazy amateur without the most basic grounding in the musical equivalents of grammar, spelling and punctuation?

Then, on the symphony’s final page, Brian did the one thing that made me decide to sit down and write this post. He wrote one genuinely beautiful and completely moving, logical and loving phrase for the cellos.

(It also begs the question of whether and how he knew anything about the opening of Mahler’s 10th Symphony)

And it was this phrase that reminded me of the symphony’s motto from Faust: “Whoever strives with all his might/ Him can we redeem” Is this single, astoundingly beautiful melody, redemption? Did Brian know what he was up to the whole time, or was he just an unhinged crank? It’s good to remind ourselves, also, that there is more than a fine line between crackpot and genius- every shade of talent from mediocrity to master lies between. Even if he was a master, who created this infuriating and bizarre work with complete command and self-knowledge, do we have to like it? It is surely about as perverse a piece as you’ll ever hear.

I guess the fact that I’ve just written about it at such length is an indication that, whatever my doubts (and I’m far from persuaded that all the piece’s frustrations are there on purpose), there is something in this music worth thinking about. Now that there is at last a listenable recording, I’m sure I’ll return to it a few more times. If nothing else, the musical history of the 20th c. has shown us again and again the dangers of giving would-be social critics too much rope to hang themselves with. Just because someone has a point, it does not always follow that the point needs to be made for 2 hours with 1000 musicians. From Brian, with all his echoes of Holst and Vaughan Williams to the Stockhausen Helicopter Quartet is not a great leap of mindset- at the end of the day, do we really want music to piss us off? Maybe we do. I can’t say. It’s got me thinking, and that’s good.

But I’m going to take David Nice’s advice and keep the garlic handy just in case I’m wrong.

Post scripts and notes:

Many people have commented on the astounding playing of the completely bonkers xylophone solo at the end of Part I without crediting the musician who played it. His name is Chris Stock, the BBC Nat’l Orch of Wales principal percussionist. Chris is also a fine photographer who has done a fair number of the headshots of me floating around out there, as well as snapping many of BBC NOW’s affiliated and guest conductors, musicians and soloists.

Other comments are at:

Programme from last night on the Proms website here.

Jessica Duchen’s thoughts here. “The White Elephant is a familiar story. We unearth a ‘forgotten masterpiece’, a work of vast ambition and grand scale and (often) British significance that’s disappeared because of a) The Nazis, b) William Glock, c) Pierre Boulez, d) Schoenberg, e) Margaret Thatcher (delete as you think applicable). It is going to change our lives and our view of musical history. There is usually an astonishing tale behind it. We enjoy a huge anticipatory build-up… and then it turns out that maybe there’s a good reason after all that the thing isn’t performed every other weekend in Weston-super-Mare.”

Andrew Clements at the Guardian “Bruckner is an obvious model; there are occasional glimpses of Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder, and most of all of Franz Schmidt’s The Book with Seven Seals, but Brian’s music lacks their consistency and personality.”

A longer response from 5 against 4 ( a blog that was new to me) here “Rarely have i felt the need to prepare so thoroughly before a concert as i did prior to yesterday evening’s Prom performance of Havergal Brian‘s Symphony No. 1 ‘Gothic’ • Books were re-read, CDs were re-listened to, & i even re-visited the writings of John Ruskin, who wrote with such authority about the nature of Gothic ”

Damian Thompson gets to the point ““This is some of the most extraordinary music I’ve ever heard at a Prom.” But for most of the time, the symphony produced the unsettling experience of music poised on the edge of genius – almost a masterpiece.”

Ivan Hewett at the Telegraph “But other things push through the music’s fabric. There’s a brutal military strain, evoking memories of the First World War.”

Edward Seckerson at the Independent “So how did the work stack up (an apposite phrase) in performance? Well, there is logic and coherence in the three purely orchestral movements, the first of them a grim juxtaposition of brutality and vain hope as a solo violin profers songful release from the killing fields.”

BBC NOW violist Laura Sinnerton on the Radio 3 website ” Much as I have complained during this week (in between mouthfuls of cake) about how difficult it was, and how, at times, I just didn’t ‘get’ the music, this has been an amazing experience. ”

Thomas in the Park hits one nail on the head: “It’s isn’t a 1920s Symphony of a Thousand, not least because it is a musical representation of horrors quite beyond the comprehension of Mahler.”

Entartete Musik ” Its sheer scale is enough to thrill, but knocking on two hours and without the orchestral or philosophical clarity of Brian’s heroes (such as Scriabin, Mahler and Schoenberg), the Gothic outstays its welcome. ”

Archived LiveBlog from John Jacob at Thoroughly Good

At ClassicalSource, a detailed review from Richard Whitehouse, who, unlike me and most other commentators talking about the piece today, obviously knows the score fairly well. “As flawed masterpieces go, no other risks so much in staking out the listener’s awareness of its greatness.”

Financial Times “For long stretches, Brian’s thick and homogenous choral writing threatens to suffocate the audience in the biggest marshmallow of sound that has ever been cooked up, but there are spectacular moments, too. The four brass bands raise hell with the unholy din they create and the massed choirs soar in glorious affirmation. It is just a shame Brian’s skills did not extend to the pithy musical idea.”

Evan Tucker didn’t like it: “Never have so many gone to so much effort for so little reward. ”

Sound Mind: “It’s difficult to describe the style of Brian’s writing in this symphony; it’s so eclectic that it echoes a little bit of everything inside its massive sprawl. It’s like a big sonic tapestry where the creator keeps changing the colour and thickness of the yarn, while reinterpreting the design, as the loom chugs along.That sounds awful, but it isn’t, really. It simply demands a different kind of listening. I’ve imagined myself as a passenger on a long train ride, with the Gothic Symphony a grand succession of unfolding panoramas that come and go as I sit back in wonder.”

London Evening Standard “Written in the years immediately after the First World War, the Gothic was Brian’s response to its faith-shattering traumas. Its first three movements were inspired by Part 1 of Goethe’s Faust, while the latter three harness the aspirational quality of the Faustian quest to a Christian text, the Te Deum, calling forth extravagant paeans of praise. Faith is unsettled by wartime experience, however, and a jaunty march for nine clarinets in the last movement presages an ambivalent ending.”

Composer Robert Hugill: “But I keep coming back to the single worry; what was it all for?”

Classical Iconoclast “If ever there was a performance that could make Havergal Brian’s Gothic Symphony work, Martyn Brabbins and the BBC Proms (Prom 4) pulled off the most amazing performance imaginable. This was total, extravagant theatre, an event to be remembered for decades to come. “And we were there!” someone said reverentially. “Pity about the music”.”

Peter Groves says: “Nowadays, one might imagine him sitting down to write his way into the record books, but it seems clear (going by the programme notes) that the flame of creativity, of inspiration, burned bright. Not just a freak show but a fantastic piece of work by a man who had taught himself to use the tools of composition and therefore produced a less polished end product than others – but one that perhaps demands greater admiration for the way in which those drawbacks were overcome.”

Brian Rheinhart really liked it: “I came expecting at best a loudly transcendent experience and at worst the ability to tell people I’d seen the world’s largest symphony. But–good lord–it was the concert of a lifetime.”

OperaToday has quite a long post, very balanced: “This performance of Brian’s “Gothic” symphony was hugely enjoyable because it worked remarkably well as theatre. Brian himself may not have anticipated the concept of sonic architecture quite in the way that others — including Stockhausen, whom Brabbins also conducts well — but the BBC Proms and the Royal Albert Hall can work wonders. ”

A follow-up from Classical Iconoclast: “. Maybe amateur and uncrafted has appeal, but you do wonder why music so fervently promoted is otherwise known only through poor performances and on deleted recordings. Maybe that’s part of the cachet. Brian is part of the grand British Eccentric Tradition. But there is so much else waiting to be discovered that one hopes attention will move to music with innate musical value. Please also see this analysis, from someone with experience of turning paper into music.”

Lisa Hirsch is just getting started, but offering good advice: “Okay, so I was not in London on Sunday. But the reviews and comments on Havergal Brian’s gigantic Symphony No. 1 are out there on the net, and I have been reading with interest and amusement. Start with Kenneth Woods, who has fascinating comments and links to other commentators and reviewers.”

Alex Ross has been reading Vftp, too: “Kenneth Woods (“incompetent … insane … moving … disturbing”).” Is Alex quoting me, or describing me? You be the judge (Given that not everyone gets my humor, let me just be clear- he’s quoting me)

Peter Graham-Woolf at Musical Pointers here and here: Part 2, a three movement Te Deum, is a huge edifice suggesting a grand Gothic Cathedral, eventually reaching a ‘racked and agonized but not-quite-despairing conclusion‘ which ultimately leaves us with ‘a mysterious radiance that abides as a light in the night‘

_______________________

Instrumentation:

Part I

2 piccolos (1 also flute), 3 flutes (1 also alto flute), 2 oboes, oboe d’amore, cor anglais, bass oboe, Eb clarinet, 2 Bb clarinets, basset horn, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 6 horns, Eb cornet, 4 trumpets in F, bass trumpet, 3 tenor trombones, 2 tubas, 2 sets (min 3 drums) timpani, 2 harps, organ, celesta, min 8 percussion: glockenspiel, xylophone, 2 bass drums, 3 side drums, tambourine, pair cymbals, tam-tam, triangle; strings [say 16.16.12.10.8]

Part two [1]:

Soprano, alto, tenor, bass soloists, large children’s choir, 2 large mixed double choruses [in practice 4 large SATB choirs]

orchestra: 2 piccolos (1 also flute), 6 flutes (1 also alto flute), 6 oboes (1 also oboe d’amore, 1 also bass oboe), 2 cors anglais, 2 Eb clarinets (1 also Bb clarinet), 4 Bbclarinets, 2 basset horns, 2 bass clarinets, contrabass clarinet, 3 bassoons, 2 contrabassoons, 8 horns, 2 Eb cornets, 4 trumpets in F, bass trumpet, 3 tenor trombones, bass trombone, contrabass trombone, 2 euphoniums, 2 tubas, 2 sets (min 3 [in practice 4] drums) timpani, 2 harps, organ, celesta, min 18 percussion: glockenspiel, xylophone, 2 bass drums, 3 side drums, long drum, 2 tambourines, 6 pairs cymbals, tam-tam, thunder machine [not thunder sheet], tubular bells, chimes, chains, 2 triangles, birdscare; strings (20.20.16.14.12)

4 off stage groups: each containing 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 tenor trombones, set (min 3 drums) of timpani

(in summary: 32 wind, 24 on stage brass, 24 off stage brass, 6 timpanists, 18 percussion, 4 keyboards and harps, 82 strings – total orchestra c190 players, plus adult choir of min 500 [assumes largely professionals], children’s choir of 100, 4 soloists = c800)

This is a wonderfully honest description of a very eccentric work. As you described it, it made me think of James Joyce’s Ulysses, where the reader can be similarly annoyed by the vast scale, the lack of narrative direction and clash of styles, but behind which is hidden a mythic framework. The drone of self-doubt, monstrous fear and visionary longing are in the end a borken and chaotic stream of consciousness. Modernity – warts and all.

Gothic suggests irregluarity and a sea of details, so a Gothic Symphony is a contradiction in terms, and indeed there is an inherent irony in aspiring to a unity which cannot be achieved. Works that deliberately fail – or works which fail because their ambition is doomed to failure – or works that show us that all human lives end in failure? The Gothic could be all of these.

Thanks for this, it’s excellent. You don’t convince me, however, that it isn’t a symphony (I don’t understand the urge to say that it isn’t a symphony). Following Cavell I would say that providing a list of features a work lacks isn’t enough to say that the work doesn’t belong to the genre, because every member of the genre will lack some of its features, even some that might be deemed essential (an extreme possibility: Alkan’s ‘symphony’ lacks an orchestra). Cavell says if two works shared all their features, they would presumably be identical.

A genre evolves because works will share some of its features and, though lacking others, will introduce new ones that shed light on prior works within the genre, thus reveal new shared paths, new extensions, new possibilities, eventually to the point that a newer contribution may lack a number of the features that initially defined the genre (which is a way of saying who cares anymore what Beethoven would think?).

You don’t need me to tell you that the Gothic does share a number of the features of the symphonic genre. But one late feature intrigues me, one that reflects upon earlier members of the genre and helps to justify the Gothic’s membership – also one that you speak of quite well – Undermining expectations, calling into question the procedures of the genre (the program notes refer to this as questioning the heroic aspect of the symphony, which gives the genre a unique and particular resonance with respect to the Great War, and demonstrates how much things had changed since Napoleon). A philosophical approach which is, in form if not substance, wait for it, quite, oh yes – Mahlerian.

Thanks again

Hello Kenneth,

I believe Brian only became acquainted with Mahler’s Eighth around 1930, when it was first performed in London under Sir Henry Wood – well after the composition of the Gothic. You are quite correct that the Berlioz Requiem is a much greater influence on the work – and it is also worth noting in a work of well over a thousand bars’ length, Hector only used his extra brass bands for under a hundred of them.

Thank you. A very fair and interesting review! And thanks for providing all those links. I am glad that Brian’s Gothic seems finally to be seen as one of the works that react, formally and philosophically, to the cultural catastrophe that was World War I. I personaly have always linked Brian to Joyce, too. So the reaction by Peter was very gratifying.

Beautifully written and a great user’s guide to this impossible-to-grasp (for me, anyway) work. And just to prove I read it all the way through, I’ll tell you I loved this line:

“…Brian’s extremely long last movement inspired thoughts more along the line of begging for mercy (a feeling which

I’m sure you, dear readers, are feeling increasingly familiar with as you reach a similar point in this essay).”

As for the latter thought: Never! Keep these up, Ken. I appreciated the snippets of other reviews as well.

Hello,

A friend on Mahler-list forwarded your piece on the Gothic to me, knowing that I had been at the Albert Hall and had posted enthusiastically about the performance on another list. I used to be active on Mahler-list but left several years ago when it went through one of its periodic obsessions with Jewish politics rather than music. I hope it’s better now.

Is it a symphony? All depends, of course on how you define “a symphonyâ€. By classical standards obviously not, but there are plenty of “symphonies†that don’t have four movements with the first in sonata form and etc. etc. etc..

I’d say that to qualify as “symphonic†a piece of music needs to be conceived on a large scale, in terms of length, variety, material, and instrumentation. The Gothic obviously qualifies on those counts. And it needs to have some overarching unity, some logic that holds it all together, gives it a sense of direction and a reason to exist and demand our attention, and gives the ability to reward it. That could be a classically worked-out key scheme, or something entirely different.

I first became aware of the Gothic some forty years ago, and I started to get to know it properly with the Ondrej Lenard recording rather more recently. Although the piece fascinated me, it was in a thoroughly episodic way – wonderful bits here and there, lots of less successful bits, and very little to hold them together. Like you I listened to the CDs in short fragments, but more because my attention would wander away than for any other reason. I couldn’t find that “long line†that would make it work as a “symphonyâ€.

So I approached the Proms performance full of expectation for the best bits but not at all confident that the whole thing would work. And of course I was excited by the prospect of the sheer physical impact of sound to be generated by those mighty forces.

The thing that really took me by surprise was that I had no difficulty at all in keeping my concentration going, and each sudden change seemed to be an entirely right and proper step along a strange and constantly surprising road – both as unexpected and as inevitable as anything in Beethoven, although in a completely different way. That’s the miracle of live performance; it can show you the parts of music that just can’t be recorded. On the whole, those are the most important ones.

There was just one brief moment a few minutes into the last movement where I got a feeling that the sense of direction had been lost and the music was starting to wander aimlessly. But it didn’t last, and Brabbins had his control and purpose back in next to no time.

Overall – and for all but a few seconds of nearly two hours of music – I had a very firm sense of that “long line†and that there was a real underlying logic and unity. But ask me to explain what it is, and I’m in trouble.

Partly it’s simple repeated patterns.

Loud bit, quiet bit. Loud bit, quiet bit. Burst of organ. Quiet bit. Xylophone bit. Timps pumping away underneath. Loud bit, quiet bit. Loud bit, quiet bit. Burst of organ. Quiet bit. Xylophone bit. Timps pumping away underneath. Loud bit, quiet bit. Loud bit, quiet bit. Burst of organ. Quiet bit. Xylophone bit. Timps pumping away underneath.

A strange kind of minimalism underneath the most explosive maximalism.

And in Part 2, unaccompanied choral bit, orchestral bit, orchestra plus choir bit, and then again. And again…

And on top of that simple structuring by repetition, you’ve got the progressive tonality thing from Dm to E. Lots of layers all going on at the same time, some going nowhere except back to the start, others moving onwards.

As you say, you can either assume that Brian knew exactly what he was doing and let yourself go with it, or try to force this monster into a cage of your own preconceptions about what music should be like. And it won’t fit!

Mahler 8. Yes I agree that once you’ve got past the facts that both are big and in two parts, first orchestral and second choral, they have very little in common. The Gothic is not in any deep way “Mahlerianâ€.

But Mahler’s influence is there – all those marches, and the moments where huge ensembles collapse down to music of great simplicity and delicacy, often with just a single solo instrument rather than Mahler’s “chamber” groupings. And there are stranger things. The very tightly worked-out harmonic logic and progressive tonality is reminiscent of Nielsen, and I heard echoes of Shostakovich and Orff – both a bit surprising, because the Gothic was written decades before either of those really got going.

And while we’re into prescience, there are a few moments with that mass of percussion (six timpanists, two bass drums, three snare drums, and more other stuff than I could count) which suggested James MacMillan’s ability to drive his music forward with gut-wrenching percussive effects as in his “Ines de Castro”.

World War 1 – yes, I felt that very strongly (and there was a strange echo of hearing Brabbins conduct Britten’s War Requiem and the Sinfonia da Requiem in an abandoned Glasgow shipyard shed when I lived in Scotland fifteen years or so ago). The Gothic is, I’m sure, about the impact of WW1 as much as it’s “about†anything.

A lot of comments I’ve seen about the Proms performance concentrate on the lack of smoothly managed transitions in the piece. Fair enough, Brian doesn’t do them. His technique is to “jump cut†– in cinematic terms – from one thing to another, and the message to the listener seems to be “I put these together for a reason, it’s your problem to know why I did it!†This isn’t the kind of music where you are led gently by the hand from one place to another, and allowed time here and there to stand and admire the view. It’s a much bigger challenge than that to keep up with him.

Alternatively, you can take the easy way out and claim he didn’t really know what he was doing.

My ears made the decision for me in the Albert Hall. Brian knew exactly what he was doing and where he was taking his listeners, and how he was preparing them for those extraordinary last couple of minutes. The solo cello brings Mahler to my mind again, but this time it’s the flute solo in the last movement of the (reconstructed) Tenth, where it sings the world back into being after the desolation of those bass drum blows in the fireman’s funeral procession. That cello passage does something similar. And the last hushed choral “Non confundar†puts the perfect capstone on it. It has to be among the best endings ever composed.

The Gothic isn’t perfect – nothing of that scale and ambition could be – but it is a pinnacle of large-scale music. I think it qualifies as symphonic, but it doesn’t bother me a bit whether it does or not.

It took an Albert Hall-full of people on an extraordinary journey and left almost all of them transported out of themselves and with an experience they’ll remember for the rest of their lives. Anyone who was lucky enough to be there knows that. What else matters?

—

he never intended to meet it.. (title of symphony) thats the point.. its just epic in its own way and I have grown to .. erm.. enjoy most of it very much!

I have just been reading the reviews and commments… I was actually singing in it and i can tell you that it has been the most complex piece to prepare that we have ever done .. the key signatures change all the time and as soon as you think you’ve got it it it totally goes off at a tangent.. we have spent hours and travelled all over for rehearsals.. Most of the choir didn’t like the piece and it caused a lot of hilarity especially during the La la la la but which nobody really gets! It was only on Friday at our final rehearsal at Alexander Palace that we actually thought ..mmm yes this is incredible..

Sunday night was the most exciting performance we have ever done and there was terrific buzz amongst all the choirs. I feel honoured to have been a part of this and will never forget the night of Sunday 17 July for the rest of my life, just a shame it was not televised!

I’m listening to the thing right now and will re-read later, but, Ken, about whether Schoenberg could draw or not: you have a problem with Gurreleider? :)

This is such a magnificent analysis of the piece that it makes me feel utterly guilty that I didn’t give it more thought. My hat completely tipped to you Ken for giving this symphony all the thoughtfulness and care Havergal Brian didn’t :).

In all seriousness though, I think the Berlioz comparison is extremely apt. But Berlioz’s innate theatrical sense always provides a sense of form, so he knows exactly when to hold back, when to build tension and when to release with guns blazing.

I wonder if, in intention at least, he was not aiming more for an Elgar super-oratorio. Now that there’s some distance, I can imagine him thinking that one of those 3,000-singer oratorio societies that were prevalent in Victorian/Edwardian England might be persuaded to take on this piece. With some distance, I wonder if he took Dream of Gerontius as a model. The way he alternates between super-solemnity and musical violence reminds me very much of that (lovely) work.

@Lisa Hirsch

Hi Lisa!

I’m a big early-Schoenberg guy, and the works of modest size, 1st Chamber Sym, string orch version of 2nd Quartet, Verklarte Nacht, are kind of party pieces for me, as is Pelleas. Nobody has ever let me do Erwartung or Gurrelieder, and it seems likely nobody ever will.

I love ALL of those pieces a lot, but they do show very clearly the limitations of his “drawing” ability. In Strauss, what looks impossible always seems to prove idiomatic- once you know the magic fingering and put some work in, everything is possible. Not so in Schoenberg, where writing for everyone tends to be awkward, and to stay difficult and unforgiving no matter how much you practice.

Likewise, in Mahler, if you play the ink, even in the original, un-revised versions of the symphonies, the balances basically work, unless there are unusual problems with the hall’s acoustic. Not so in Schoenberg- all of those wonderful early works, even the chamber works like the First Quartet, have balance problems all over the place. Of course, Schoenberg is pushing boundaries, but in similarly intense works like Elektra or Mahler 7, you just don’t have those kinds of problems to solve. So, genius, yes, master craftsman, no….. Unlike Mahler, Elgar, Berg and Strauss, there are problems, but they’re worth solving.

Just my two cents!

Ken

Thank you for this superb, wide-ranging article. I admire your honesty, insight and generosity in revealing so much more about the piece than those poor critics! Mr Clements does not seem to have spotted that the Gothic pre-dates Schmidt’s “Book of the Seven Seals” by over a decade!

The work does seem to me closer to “anti-art” (rather like Satie or Varese) in its curious mix of the hi-falutin’ and low humour – I too was laughing aloud at that jarringly jaunty clarinet march – and though I don’t think Brian was “having a joke” (quite the reverse) I think he was on to something which he couldn’t quite analyse within himself. If he’d been able to sort it out intellectually, what music might he have written? Instead, he remained ain instinctive post-modernist stuck in romantic forms. Unfortunately, it was all going on in his head instead of in a concert hall. Thank you again!

Hi,

Good article, Ken. I am curious, in context of The Gothic, what do you think about some other large scale works that successfully step on or ignore transitions? Examples – Shostakovich Symphony No. 4 is a brilliant work with so many ideas that go nowhere, but it is held together by its variety, complexity, uniquely creative vision, and ultimate concluding stillness. I like what wiki says about this work:

‘If the first movement of a symphony succeeds as a musical statement only by following the rules of traditional sonata form fairly closely, then the Fourth Symphony’s opening movement initially comes across as a colossal failure. Closer examination reveals what has been described as “a hide and seek relationship with sonata form.” Even more detailed study shows that Shostakovich is using his favored version of sonata form, wherein the recapitulation presents the material from the exposition in reverse order. The composer’s very effective obscuring of this approach makes understanding the movement’s structure quite difficult compared to most of his other symphonies.’.

Other examples of form challenged masterpieces: Scriabin’s late works like Prometheus (and especially the Mysterium which is on similar scales of the Gothic), Charles Koechlin, Hans Werner Henze, etc. Recall back in the 1920’s, the music tradition was being challenged in terms of scale, harmony, and structure. Sibelius No. 7 is a perfect example of pushing the structural boundaries while remaining in debt to a tradition. I’ll grant Sibelius 7 is a tightly constructed piece, but the point is – what is so bad about having a tremendous scale lacking formal structure with overt transition? Shostakovich 4 worked brilliantly without a coherent structure – here is the ultimate point I want to make: sometimes the composer chooses to only let you understand what the point of all that music was after the work is finished and not while you experience it. This is one of the great things about music – its meaning is explained over time as it is experienced. I believe Shostakovich 4 works brilliantly because it feels random but in the context of its concluding desolatation, it makes you recall what all you’ve witnessed in context of the coda. If that piece had ended 5 minutes earlier than it does, it would have left the listener with an entirely different understanding of the piece. That means its structure is not obvious until you look at it from a distance. This is why the Gothic doesn’t need to be so formally cohesive as a Beethoven, Brahms symphony would. The last moments make you understand the context not previously laid clear before. What do you think?

@karim

Some very interesting thoughts, Karim. I was actually smiling the other morning at the thought that the two symphonies I’ve written the most about in the last month or so are Sibelius 7, which I just played with a chamber orchestra of about 40 players, and the Gothic. I’ve continued to warm to the Gothic, which has certainly had an impact on me, but the Sibelius probably has more impact, even though it’s just over half the length of the last mvt of the Gothic. You could play the Sibelius about 5 times in the duration of the Gothic, and the 1000 performers would be enough people to populate 20 Sibelian orchestras.

The Shostakovich is an interesting comparison. Both works live or die by whether or not the Coda “works” in performance. I though the ending of the Brian was very well handled on Sunday, although the choir struggled with tuning just before the end, the last soft singing was magical. That and the the astounding cello melody just about mad the symphony.

Of course, Shostakovich could “draw” like only about 5 or 10 others in history. For sheer freakish technique in every area- orchestration, counterpoint, harmonization, motivic development, he’s right up there with Haydn, Mozart, Mahler, Brahms and Bach. How would that kind of technical ability reshaped the Gothic? Would it?

Thanks for writing

Ken, I love Sibelius very much and especially the 7th. I would have loved to have performed that. You can clearly see Sibelius worked hard at being as concise as possible (especially if you’ve heard any of the Vanska original versions that are longer and always more clumsy than their revised forms). But I think what must be considered is how the music fits into the composers goals.

Here is what Scriabin said of his “Mysteriumâ€: “There will not be a single spectator. All will be participants. The work requires special people, special artists and a completely new culture. The cast of performers includes an orchestra, a large mixed choir, an instrument with visual effects, dancers, a procession, incense, and rhythmic textural articulation. The cathedral in which it will take place will not be of one single type of stone but will continually change with the atmosphere and motion of the Mysterium. This will be done with the aid of mists and lights, which will modify the architectural contours.”

Scriabin intended that the performance of this work, to be given in the foothills of the Himalayas in India, would last seven days and would be followed by the end of the world, with the human race replaced by “nobler beings”. Fortunately (or not depending on your point of view) his efforts did not succeed however based on the scale of his vision, you could imagine the work was not scored for a string quartet but rather thousands. Remember the goal of the Gothic is extremely vast incorporating all of Western history within the context of man’s eternal struggles to conquer his/her insurmountably lofty goals. There are similar works of oversize megalomania around this time period. My point is that the composer’s goal of the vision has to be considered when rendering judgment on how vast the forces needed to execute their vision is. That is why Sibelius’s lifelong striving for conciseness and Havergal Brian aren’t really comparable in scale. The Brian is truly an all enveloping idea and that is how he conceived and executed it. I do grant a more refined composer could have utilized the forces with more restraint and likely have been more successful at their efforts, but I also get the idea Brian was trying to say. To me it is like wondering why did Beethoven hold off on the trombones until the finale of his Symphony No. 5 or why did he hold on the choir until the last movement of No. 9? Because he wanted to heighten the impact of introducing their presence since it was withheld for so long. It works brilliantly that he doesn’t use these extra size at his disposal with more frequency throughout the work, but to me, this is exactly why the extra brass bands work so well in Brian – the full orchestra isn’t used that often is a positive quality.

What to you is more important…the musical ideas or how well they are executed? I’ll grant there are a handful of masterpieces that have brilliant ideas that are flawlessly executed, but that combination is extremely rare and probably doesn’t fit 99% of most successful works which I’ll define as works that have entered repertoire with some predictable connection made between audience and performers. It seems like in general you prefer the execution of an idea to its quality. I realize this is all subjective conjecture, but it is a pretty safe bet that Mussorgsky falls into the category of great ideas that are poorly executed. Whereas someone like Schoenberg might be a better craftsman than idea originator. Shostakovich, who clearly had tremendous technique, might not have had the most distinctive ideas. For example, what he does with DSCH is always brilliant but his Symphony No. 7 could be considered overlong however still thoroughly successful in achieving its musical goals.

On a separate note, I didn’t quite understand your criticism here: “I was close to laughing out loud, such as some of the ridiculously over-the-top silent-movie-spooky-castle music, replete with mega cliché’d organ writing”. So it conjures up in your imagination the image of spooky castle, but that isn’t a fair criticism of the music. Why would you consider this cliché if it proceeded practically all film music? It is like calling Bach’s “Toccata and Fugue” a cliché because it is used in so many haunted castles.

@Christopher Webber

Hi Christopher

Thank you for the comment and the kind words. I’ve been debating a friend on the question of whether it’s a symphony or an anti-Symphony. It certainly seems determined to attack and undermine the norms and expectations of the symphony. It is certainly a start rebuke to the comforting idea of the Beethoven-ian symphony in which striving leads to transcendence. At least it seems that way until the Coda, which may be transcendence or Faustian redemption.

Mahler 6 is about the only other large scale symphony I can think of that so completely turns the symphony on its head. In that piece, the role of tonality is completely transformed- the tonic (A minor) becomes something to be avoided, and is always returned to via collapse rather than through culmination or release.

Collapse seems to be key to Brian’s thinking as well. Very interesting music the more I think about it, whatever its frustrations!

@Sasha

Sasha

Thank you so much for your comment- it’s a gift to listeners to know something about what it felt like to sing that Leviathan. What a project for all of you.

@Philip Legge

Many thanks for the comment, Philip. I know you know your Havergal Brian, so the information is much appreciated.

@karim

Hi Karim

You point quite rightly that it’s not fair to compare Sibelius and Brian, since their aims were obviously different. It’s not quite what I meant to do– the question you ask “What to you is more important…the musical ideas or how well they are executed?” implies that these comparisons are competitive, when they should be instructive. Scale aside- let’s accept for the sake of argument that Brian’s vision and material and inspiration were all quite extraordinary in this piece. As good as Sibelius, if you like! The question I struggle with, and I haven’t come to a decision, is how much of what is in the piece that is perplexing or frustrating is there of necessity, and how much is the result of a lack of care or skill? I honestly don’t know. I do feel like the unidiomatic writing for choir hurts the piece. Even with those astonishing choirs on Sunday, there were sill big pitch problems. It’s a pity he didn’t hear the piece when it was written and then he could possibly have revised some of it.

Shostakovich 7 ought to be a cautionary tale for anyone who would write about music- so many commentators have gotten it so badly wrong. It’s a great, great piece- a true masterpiece in every sense. Having been conducting a fair bit lately, I can say with absolute conviction that to criticize it is to demonstrate your misunderstanding of it. With that example in mind, my impulse is to give Brian the benefit of the doubt and to get to work on learning the Gothic well enough to answer some of my questions about it from the source.

Thanks for the comments!!

I was at the performance, and I seriously think that in most ways, it was the best so far (it’s definitely the first time that so much of the fine detail has been perceptible: all possible credit to Brabbins.) The choir pitch drift was undoubtedly a problem (I seem to remember that at the 1980 performance, they distributed the BBC Singers (all with absolute pitch) throughout the choirs: shame they didn’t do it this time.) I too felt that in some places, the xylophone was a bit prominent in the second part – but usually in these passages, the glockenspiel plays along with the xylophone, and I felt that maybe the problem was that it was not prominent enough, so that the glittering effect was lost. I would have liked to tell the glockenspielist to bang a bit harder.

One of the things which really baffles me is when I read (here and elsewhere) the contention that there is little or no development in the Gothic. There IS! – but it takes some delving to see it (I’ve been delving for nearly 40 years and I feel that I’ve still only scratched the surface.) It’s difficult in this context to give examples, but I’ll try – please bear with me! Listen to the opening of movt.2 – the dotted figure at the opening, and semiquaver figure in the last bar of the majestic main theme which comes a few bars later – then, with them clearly in mind, just listen to the rest of the movement and see what Brian does with those two figures: it’s amazing, and shows a composer of consummate skill.

Another example (this one’s going to be really difficult to talk about.) Movt.3 can seem as though it consists of violently-contrasting episodes with no thematic connection or continuity. But there are a few short motifs which underly and unify everything. The most obvious is the four-note triadic phrase which appears in the woodwind soon after the opening (harking back to the start of the first movement); watch how it develops through the quiet F major section which follows, and then underpins the loud section in D minor which comes next. Then, in that section, there’s a passionate theme in the violins, and in bars 11 and 12 of this is a kind of descending flourish. Now listen to the climactic passage leading up to the violent change of key before the opening ostinato figure from the opening returns: virtually all the brass writing here is developed from that two-bar figure. Another vital component in movt.3 is the four-note chromatic descent in the deepest bass, usually trombones (B flat – A – G sharp – G – it first appears in the second slow/quiet section, underneath harp harmonics.) It recurs throughout the movement, and then finally in the section with the xylophone, where the music seems almost paralysed, it seems to blast a way through into the next section. (I really don’t know if any of this will make any sense, written out like this: maybe worth mentioning that the (reprinted) score is – believe it or not – still available for sale: it’s done by United Music Publishers, and it ain’t cheap, but in my view worth every penny!)

And as for there not being any climaxes – well, Ives once wrote to a friend: “Are my ears on wrong?” – and I start to wonder if the same should go for me. No climaxes?!! What about the build-up towards the end of the second movement leading to the overwhelming return of the main tune? And then from this peak, it continues to build in intensity, via the rhythm of the main tune’s opening bar, until it reaches a moment of clear C sharp major, with a triumphant peal of trumpets like sunlight bursting its way from behind clouds. It’s not just climactic – it’s orgasmic!!

As I say, I’ve been delving into Brian’s music for a long time – but the delving continues to fascinate me and probably will for the foreseeable future. Why did I start delving? Presumably because I heard or felt something in Brian’s music which gave me the sense that there was something worth delving for. (It occurred to me the other day that it’s analogous to a potholer seeing an insignificant hole in the ground and feeling a draught of air emerging from it – a sure sign that a (maybe spectacular) cave lies beneath – all he has to do is to dig down to it.)

Apologies for the length of this – I hope it makes sense to someone.

Kenneth – you say you’re inclined to try some other Brian. Give no.10 a go – it’s always been one of my favourites, and it’s only about 20 minutes long.

@Peter Duffy

What a fantastic and interesting comment, Peter. Thank you for sharing your love of the work, and especially for taking the time and trouble to give some detailed descriptions of what you have discovered as you have gotten to know it over many years. I’m just so pleased that my original blog post has provoked so much interesting discussion from everyone here.

Hi Kenneth – glad you liked it! It just seemed as though it was time that we got down to a bit of nitty-gritty.

Incidentally, I’ve realised I made a bungle! The low B flat – A – G sharp – G motif in movt.3 actually first appears a few minutes earlier than I’d stated (whilst the opening ostinato figure is still going on.)

I thought I might jot down a few random ramblings about the Gothic and Brian in general – hope they prove of interest …

Firstly, I feel that I should make it clear that a lot of my views and ideas on the Gothic and other Brian works are based on work done by other scholars – in the 1970s and early ’80s, Brian’s work underwent a lot of examination and study. The most comprehensive is the three-volume guide to all 32 symphonies by Malcolm MacDonald (Kahn & Averill – think they’re still in print); there’s also two superb large-scale studies of the Gothic, by Harold Truscott and Paul Rapoport, published by the Havergal Brian Society. The best general book on Brian is undoubtedly “Havergal Brian: the man and his music” by Reginald Nettel (pub. Dobson) – riveting reading (the original version – published in 1945 – was called “Ordeal by Music: the strange experience of Havergal Brian”.)

Newton once said that if he seemed to see further than others, it was because he stood on the shoulders of giants: that comment definitely applies to me also!

When Brian came to write Part II of the Gothic, one of the problems he faced was that there was no score-paper available with enough staves! Schoenberg apparently hit the same problem when he came to score “Gurrelieder”: he apparently solved the problem by commissioning a printer to print some for him. Brian presumably did not have the financial resources to permit such a way forward: instead, he used a solution suggested by a friend – gum together sheets of 32-stave and 24-stave paper. The resulting 56-stave score, when complete, stood over a metre high, and the gummed joins gave it a big bulge in the middle (one comment was that it looked like a pregnant woman.) Like many of Brian’s other scores, it is now lost. Losing scores was a strange problem which plagued Brian throughout his life: the Brian Society has for a long time been offering cash rewards for information leading to the recovery of them – with some notable successes.

Some people may be wondering what else Brian wrote, apart from the 32 symphonies. Well, for a start, there are five operas: “The Tigers”, “Turandot”, “The Cenci”, “Faust” and “Agamemnon”. “Turandot” is based on the play by Gozzi (as also used by Puccini); “The Cenci” uses Shelley’s play; “Faust” is based on Goethe; “Agamemnon” uses Aeschylus (it’s a one-act opera: Brian envisaged it as a prologue to Richard Strauss’ “Elektra”)

“The Tigers” deserves a bit of comment to itself. It’s a burlesque comedy, written almost concurrently with “The Gothic”, to a libretto by Brian himself. It focuses on the insanity of war (several commentators have noted that it seems to anticipate Spike Milligan’s Goons by about 35 years.) The Tigers of the title are a regiment of bungling soldiers. For many years, “The Tigers” could not be performed, as the full score was one of the lost ones: however, in 1978, as a result of the HBS’s reward offering, it turned up (three enormous green-bound volumes, found in the basement of the publisher Southern Music. How they got there is still a mystery.) A concert performance was mounted and broadcast by the BBC soon afterwards – but so far, it has (most regrettably in my view) not yet been staged. (The vocal score was published and I believe it is still available.)

In the pre-Proms talk for the Gothic, Sarah Walker talked about movt.3 and the xylophone passage, and how it seemed to suggest the demonic aspect of gothic architecture – the gargoyles and other grotesque carvings. About half-way through “The Tigers”, there is an astonishing orchestral/ballet episode called “Gargoyles”: for a few minutes, the comedy is put to one side and the mood becomes deadly serious, even nightmarish. Brian writes the stage directions and choreographic outline into the vocal score. A cathedral tower gradually appears out of the darkness, surrounded by grinning gargoyles: to fantastic music which is very akin to movt.3 of the Gothic (it even includes a xylophone), they come to life and march around the tower. As the music reaches its climax, they become filled with a fiery glow until enormous tongues of flame rush from their mouths. (It’s one of my most fervent wishes that this opera could receive a full staged performance: the effect of this episode alone would be devastating!)

Other Brian works include several shorter orchestral symphonic poems and overtures; five “English Suites” (no.5 was recorded in the ’70s); concertos for cello, violin and orchestra; a lot of solo songs and partsongs; a small number of (nevertheless interesting) piano pieces (republished by the HBS in a single volume); and a number of choral works – including one, a setting of part II of Shelley’s “Prometheus Unbound”, which is his biggest work of all (calling for even bigger forces than the Gothic.) But it can’t be performed – the full score is lost!!

I’ll stop there for now. Hope I haven’t bored anyone …

Quantity is never a substitute for quality. It is conventional for composers to keep their ‘big tunes’ for the second or last act. However, it is very self-indulgent to get an orchestra to play for 110 minutes then throw in a cracking tune at the end – is this cocking a snook? It doesn’t endear Brian to anybody.

A long thread of comments on David’ Nice’s review at The Arts Desk (I am still laughing at his statement: “Now I’m hanging out the garlic and spraying the air freshener to keep Brian’s other 31 symphonies at bay” has finally worked its way over to the Vftp slums as my comments about Brian’s expertise with Latin came into play:

“The claim that Brian admitted that he didn’t know what the Latin words meant appears in the Kenneth Woods ‘View from the Podium’ website. The notes for the Boult CD include ‘I had intended using Latin, German and English words. I am using only Latin words, for my German prayer book is with my books in Stoke…'” in a comment you can read here: http://www.theartsdesk.com/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=4137:havergal-brians-gothic-symphony-bbc-concert-orchestra-bbcnow-brabbins-royal-albert-hall&Itemid=27#comment5640

This was in response to a question from Mr. Nice himself here:

http://www.theartsdesk.com/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=4137:havergal-brians-gothic-symphony-bbc-concert-orchestra-bbcnow-brabbins-royal-albert-hall&Itemid=27#comment5639

I’ll past my response here:

“The full quotation in which Brian articulates his discomfort with Latin (which I attempted to put a slightly humorous spin on and probably shouldn’t have) is from a letter to Granville Bantock, quoted on the Brian Society website;

” I know nothing of the Latin language—I know something of Italian and have used this knowledge in deploying the words in syllables—but they may be wrong and if so may appear foolish. The Te Deum is written in three sections. The first Vocal Score is copied out. Do you think you would have the time just to look it over and see that my excursion into Latin is OK.†[Havergal Brian to Granville Bantock, 27 June 1926. Quoted from Kenneth Eastaugh, Havergal Brian – the making of a composer, London 1976, p 251.]

You can see the quote and the citation here:

http://www.havergalbrian.org/threebs.htm

Obviously, the piece inspired a mixture of wonder, perplexity, doubt, outrage and admiration in me during the concert. What it left me with afterwards was a great deal of curiosity, and surely the fact it has inspired so much debate and discussion is a sign that it does what great art should. Music is probably the most relevant when it divides opinion the most violently. Mr Nice was surely right when he said “this was exactly the sort of thing the Proms should be trying.””

You can see the comment in the orignal thread, which has a lot of interesting and contentious discussing, here:

http://www.theartsdesk.com/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=4137:havergal-brians-gothic-symphony-bbc-concert-orchestra-bbcnow-brabbins-royal-albert-hall&Itemid=27#comment5652

@David Galvani

One thing I think even the most ardent Brian-ian would agree with me on is that Brian wasn’t trying to endear himself to anyone!

@Peter Duffy

Fantastic stuff, Peter. Keep it coming.

Don’t underestimate Brian. The xylophone bit is brilliant and Faust went mad at the end (hint, hint).

This symphony takes me on an emotional journey which I don’t understand but find exhilarating and worthwhile. The talk of the length of the piece and it’s scale is to me is irrelevant. I enjoyed it so stuff all that academic, clever clogs talk, what an achievement it was by Brian. If the critics don’t like it, I’d say to them don’t listen to it. Seems to me , that the composer wouldn’t spend all that time composing for the sake of it.

As with paintings, for me, the measure of a work of art is how it affects my emotions……and Brian’s music affects them profoundly.

I don’t feel competent to add anything – I don’t understand the piece, I want to like it but I’m not sure it wants to be liked. However I did want to say that, for me, the old Boult recording was a revelation because here at last was someone making sense of the idiom of the piece and at least potentially communicating the ‘story’ of the piece. Sure, the detail and sound in the new recording is miles better, and I’m sure that Brabbins ‘gets’ it too, but for me Boult still feels like the best chance of finding a way in. In case that’s any help to anyone else hoping one day to make sense of this monster!