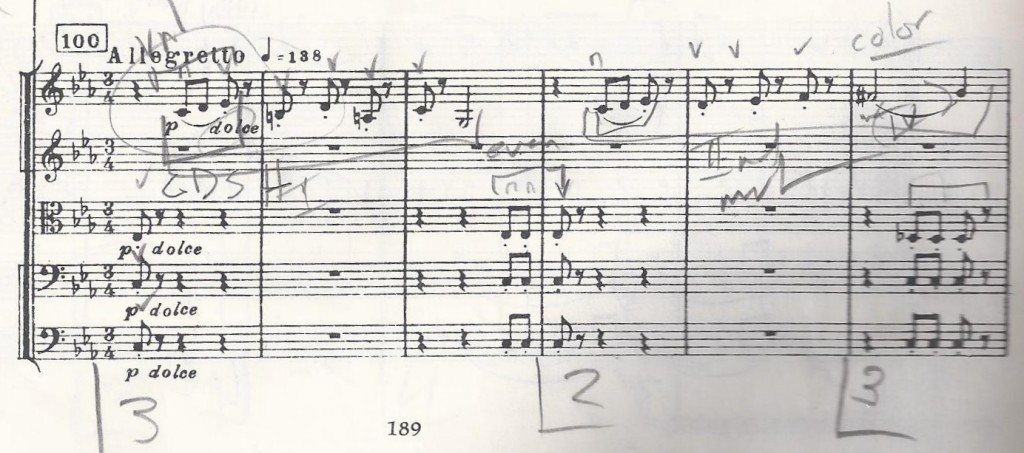

The excerpt above is the beginning of the 3rd movement of Shostkovich’s 10th Symphony, a work I conducted last week with the Kent County Youth Orchestra.

Shostakovich 10 is a serious piece, and a seriously difficult piece.

When news gets out that I’m doing a piece like this with a youth orchestra (“Shostakovich 10???? With a youth orchestra? Good luck….”), many friends and colleagues ask how on earth “the kids” will play something like the 2nd Mvt, which flies along at such terrifying speed.

The short answer is that I never worry about fast tempos with young players. The loud, fast music always sounds awful at the first rehearsal, and like the Berlin Phil at the concert.

(The long answer is that the last time I did the bloody piece was with an earlier incarnation of the same orchestra, so I know it will work, so bugger off with your condescension please….).

People never really believe you when you say that the real difficulties in a piece are all in the slow, soft, transparent music. This is because they think you’re talking about artsy-fartsy difficulties like creating a magic sound cloud that will make fairy dust fall from the ceiling of the auditorium and make bitter old men feel young and hopeful again.

No- when I say the slow, soft, transparent music is harder, I mean it’s actually much more difficult to get the musicians to play it in tune, together and with a sound that doesn’t make you wish you were somewhere else. It’s not artsy-fartsy hard, it’s actual nuts-and-bolts hard. It’s hard to make it not….. sound like shit.

Here are the 10 “real” most difficult passages for any orchestra in Shoatakovich 10:

10- The very beginning for basses and cellos. Extremely exposed for tuning, easy to rush.

9- The piccolo solo at the end of the first movement. They tend to pass out and die before the last note in the strings

8- The long passage in octaves for violin and viola beginning at fig 47 in the first movement. This is actually loud, but still slow, and is incredibly difficult for tuning. All of the 20 or so recordings I have are teeth-grindingly out of tune on at least a few notes in this passage.

7- Figure 94-97 in the 2nd movement. This is actually fast, but soft- the only soft music in the movement, and far more terrifying for it. Very tricky intonation for first violins. Being in octaves should help, but somehow makes it harder.

6- The brass syncopations in the last movement from 7 after 204until 4 before 205. Finally- this passage is loud and fast, but still often falls apart in concerts with even the best orchestras

5- The beginning of the Allegro in the last movement. Still fast, but very soft, and terribly, terribly exposed. A killer for any first violin section

4- The woodwind chorale in the first movement at figure 65. Really tough for tuning and balance. Slow, soft and infinitely exposed. One wants the G major chord at the end to be painfully beautiful. Often, it is just painful.

3- Figure 185 (“Listesso tempo) to figure 192 in the Finale. The tempo (which should just stay the same) seems to give many conductors great trouble here, notably Mravinsky of all people. This is made worse by the strings tending to approximate the rhythm in the tune. The intonation in strings is very difficult and the counting for cello, bass, trumpet and trombone is extremely treacherous at each return of the DSCH motive (because Shostakovich writes a different metric trap every time).

2- The Introduction (Andante) to the Finale. Shostakovich marks a temp of 8th=126. This is an extremely uncomfortable tempo- as was his intention. If you beat it in 8th notes, as per the marking, it feels very busy and tends to make it quite uncomfortable for the wind players to breathe and feel where the phrase is going. If you beat it in dotted quarter notes (as every conductor I’ve seen do it has), the tempo is painfully slow, made more uncomfortable by the many silences. Many conductors end up rushing or simply going far faster than the tempo (where Shostakovich actually plays it quite slowly in his own recording- listen). The live Mravinsky recording from the 80s is a vivid example of all that can go wrong- a tempo out of control, players getting lost, and a not-very-nice sound (and I’m about the world’s biggest Mravinsky fan). Not only does he start faster than marked, he cuts many long notes short, rushes through rests, skips the ritenuto before fig. 152 completely (granted, he may have been rattled by some of the 1st violins coming in a half bar early in the 3rd bar of fig. 151) and makes a huge, un-marked accelerandeo in the 3rd and 4th bars of 152. It is that kind of passage. If anyone loses focus for second, it can go horribly wrong. I find it an extremely draining passage to conduct- it takes incredible intensity and concentration to bring it off. It is easy, painfully easy to miscount. (Note also that the Shostakovich performance of the Introduction is nearly a minute longer than the Mravinsky- a good example of why we shouldn’t just assume automatically that someone who knew and worked closely with a composer was always the closest to the composers wishes).

1- The beginning of the 3rd movement (pictured above).

You may well look at this very simple passage and think I must be out of my mind. A month ago, based on my previous experience conducting the piece, I would maybe have had it as low as 3 or 4, and with a pro band, it might be slightly more easily handled. Still, even with pro’s, it is difficult, and one rarely, rarely hears a performance that brings to light all the contradictions and tensions that are there on the page.

As with the opening of the Finale (and to a certain extent, much of the 1st movement), the tempo Shostakovich asks for is deliberately uncomfortable. At 138, beating in 3 feels busy, in 1, however, it lacks tension. If you play it right, it doesn’t feel good.

Tension is what this opening cries for- there is so much metric ambiguity in play, and if this opening sounds comfortable, it dies. The melody is written so as to obscure where the barlines are, and the phrase-lengths (or bar groupings) are extremely irregular throughout the whole opening section.

Many conductors allow the music to roll forward to a more comfortable, faster tempo than what Shostakovich marks. I’m sure it feels far more natural and safer on stage, but, in my opinion, much of the mystery, anxiety, treachery and intensity is lost. Too slow, on the other hand, and music simply plods, and the alternation of 2 and 3 bar groupings gets lost because everything sounds like a “main” beat. Shostakovich’s own performance of the opening on piano is virtual masterclass in walking this knife-edge of a tempo in the first five bars (although he and Weinberg also fall into the trap of rushing as the passage goes on- Shostakovich was a notorious rusher at the piano, as you can hear in the famous recording of him playing his 1st Concerto, a performance I admire, even adore, but would be terrified to accompany). Listen to how Shostakovich and Weinberg play this opening on the paino. Note the incredible clarity of the silences between each note in the first 3 bars, but also notice how, even by the 4th or 5th bar, Weinberg (playing the upper part) is very slightly rushing and the silences are no longer as intense or poised.

Now, at this point, with all this talk about tension, tempo and atmosphere, you probably think I really am talking about artsy fartsy difficulties here. It can’t actually be that technically hard, can it? Not in a way that is perceivable by Joe Public?

Well, in my experience, it is.

The primary difficulty in this opening is rhythmic. Everything about it wants to rush. There are certainly things that always seem to rush in every orchestra everywhere in the world. This excerpt has them all.

1- Short/staccato notes. Note that in the first 5 bars, almost every note is short, but for a couple of slurs and one half-note.

2- Repetitions of the same rhythmic unit. From the 3rd beat of the 1st bar, the 1st violins are moving on exactly every beat 6 times in a row. Note that this is compounded by the notes being short (No. 1 above- that’s why this opening is slightly tougher than the opening of the symphony, which is also made difficult for being mostly made of the same note values, moderately paced quarters on the beat. Cellos and basses tend to rush the opening of Mvt I some, 1st violins tend to rush the opening of mvt III a lot). All of the punctuation in the viola, cello and bass is also repeated 8th notes, which also tend to rush.

3- Repeated bow strokes rush. Most conductors (including me) ask for all the staccato notes in this tune to be up bow. It sounds cool, but can rush more.

4- Slurred small notes under a slur in moderate tempo. In this case, the slurred 8ths, not so much at the beginning as in the 8th bar (not shown).

5- Any request for something contradictory or unusual- in this case, the dolce marking forces the players to really think about their sound. It looks completely out of place among all those staccato dots (and most conductors don’t seem to bother with it). The tension of trying to achieve it can also increase anxiety, leading to rushing.

6- Anything being played by musicians under the age of 25.It’s a truism of conducting that pro bands drag and youth orchestras rush.

I always knew this passage would cause us some trouble.

The first reading was just that- a reading. Better in some ways because, buried in their own parts, the first violins seemed blissfully unaware that this passage was hard.

However, once the first player starts rushing, a young section quickly erupts into bloody civil war. The rushers rush to catch up, the draggers start accenting every note and playing behind the beat. People start pumping their scrolls up and down, banging their heads to show the tempo like they were in the front row of an Iron Maiden concert.

The first thing to try to fix this as a conductor is to use your hands. You can either pick a couple of important beats and make your ictus extra distinct (the “clear beat” solution), or actually stop beating and try to force them to come to an agreement (the kabuki dance solution).

In this case, one is really dealing with a breakdown of trust- the players don’t trust each other to play at the right time, so either they race ahead so as not to fall behind the player they think will come early, or they actually play behind the conductor in hopes of making a point to their colleagues.

Psychologically, it is important to restore trust as quickly as possible. The first goal is to get away from people arguing over when is the “right” time to play, or even what the right tempo is. One has to get the section breathing and playing again as a unit.

The clear beat solution only works in the least severe situations because it is actually emphasizing the importance of playing at the “right” time, rather than giving the players room to play together. In other words, if the opening sucks just a little, clarifying the gesture may help bring it back together, but if it is really swimming, a smart conductor will go straight to dropping the hands or doing a little kabuki dance.

However, if the players are already flailing and cueing and head-banging, they’re just replacing your over-conducting with theirs. Not conducting is not enough. One might plead for a more pliable, softer-edged approach from the players, but often, once trust breaks down, a few well-intentioned, would-be heroes can’t stop leading from the 12th desk and continuing to cause problems.

Perhaps one needs to properly rehearse from a pedagogical point of view?

Technically, the key to not rushing is subdivision- keeping track of every 8th note through the silences and long notes. This we did in the string sectional, using one of my favourite rehearsal tricks. Instead of the printed rhythm, I have the musicians play straight 8th notes, filling in all the rests with repeated pitches, and changing bows on every 8th in the half-notes. Instead of dido-di-di-di-di-di-dahhhhh, they play dido-dido-dido-dido-dido-dido-didadidadida. We then have the outside players play as written while the inside play straight 8ths, then switch. Perfect every time.

Until the next, penultimate rehearsal, where the players’ nerves kicked in and it was worse than ever. All it takes is for one player to not trust his or her stand partner to have learned the lessons of the pedagogical exercise, and it quickly turns back into a turf war over who is playing at the “right” time.

A new approach was called for. We needed to find a way to force players to play together and not fight each other or try to lead or correct in anyway. We needed to restore trust.

I asked the first violins to close their eyes and play it alone, without the low-strings. After rehearsing it so many times, everyone seemed to have it memorized anyway, just as they’d memorized the train-wreck. So they would know when to start, I counted “two, three, One!” and they played.

It was, I exaggerate not one jot, magic. Such poise, such color, such tension and intensity and blend. Every note perfectly together.

Fast forward to the dress rehearsal the next day. We’d just ripped the 2nd movement to shreds (that’s a good thing). After a quick re-tune and towel off, we started the 3rd mvt. The combination of more adrenaline than the players were used to from the 2nd mvt and the time to get uptight while tuning was too much, and it all went south again. The players were squabbling through their violins like a bunch of cousins at a Georgia-style family reunion. Everyone must have thought that the upshot of all that hard work was that they now knew EXACTLY when to play. Everyone was now that much more insistent. It’s the kind of moment that makes you want to scream with frustration “why does this still sound like shit?!?!?! We’ve worked and worked on it?!?!?!? Can’t you just play together!?!?!? The only right time is at the same time as everyone else!!!!!”

Instead, I took a few slow, deep breaths and counted to 10.

“Okay,” I said, “eyes closed again…..” This was my last chance. Whatever I tried this time had to work, or the concert was likely to suck, at least for these 10 bars or so. I checked my sleeves carefully for one last trick. Was there one last, lonely rabbit still hiding at the bottom of my well-worn hat?

“Eyes closed, but this time…. I’m not going to count you off.”

The leader quickly identified the problem with this approach. “How will we know when to play, or how fast?” she asked.

”The low strings will play the first note.”

She and her colleagues thought about my answer and looked at me with some suspicion. Since the low-strings only play a single, short note, there is no way it can be used as an indicator of tempo. As a matter of common sense and practicality, I had not addressed her concern. This was my intent.

“You’ll listen and sense when everyone breathes, and it will work.”

The first violins all dutifully closed their eyes.

I gave the low-strings a silent upbeat. They played first note.

And the violins, with nothing to rely on but their ears, played like gods.

Lesson learned, they did so again in the concert.

Copyrighted material is reproduced here completely without profit for educational and discussion purposes under relevant Fair Use law, which may vary from country to country, and will be removed on valid request.

I wish you had told me all this at the time.

great article. it got me to listen to multiple recordings of the 3rd movement.

“I truly appreciated reading the breakdown you shared… THANK YOU… and keep on keepin’ on!

While reading your post, I can see you sweating on the podium Ken (how about this as the title of your blog? :)) but all I am able to do, is laugh about your description, while I’m thinking back how many times I’ve noticed similar moments in our amateur orchestra (I’m definitely guilty of head-banging :)).

Wonderful blog post, Kenneth, on the nuts & bolts of conducting the 10th. Most revealing, especially the links to the musical examples from the composer/Weinberg and 1980 Mravinsky recordings and their widely contrasting tempi.

Mravinsky surely did have jackrabbit sensibilities when it came to tempo, a quality that worked magnificently most of the time. But in the later recordings his barnstorming tempi, as you point out, could lead to wholesale butchering of entire passages, even entire performances — as in his later, seemingly willful vandalism of the 12th.

One passage I thought might be particularly challenging in the 10th is the one that begins around fig. 180 in the finale where a number of melodic streams increasingly fall out of sync with one other to climactic effect. Apparently it’s not on the “top ten” list of provocative passages. Fascinating, in any event, to know that the delicate parts rank among the most difficult, and precisely why.

Louis

Thanks for this post, Ken. I had my first sight-reading session of the year with my youth orchestra string players yesterday and came out exhausted–this gives me many specifics to focus on and study since so many of the same issues were present both in the playing and my conducting. Thankfully I have another week to prepare!

Also, you nailed an issue in words that is a prime reason why I stopped playing with one of my local groups–the breakdown of trust within the string section. I never could quite put my finger on what irritated me so greatly, and that was it.

@Greg Austin

Hi Greg!

There’s nothing more frustrating than playing in a string section where some people decide they are the arbiter’s when the right time to play is. The only right time should be with everyone else- from there, the conductor and orchestra can decide on faster or slower, earlier or later, but if players can’t trust each other, everything becomes an exercise in frustration. Hope all is well back in the homeland!

Ken

@Zoltan

Hi Zoltan

Not to fear- I take these things in stride, and I knew this group well enough to know there was a solution. The real sweating was in the concert when it was over 100 freaking degrees on stage, and I was being Mr intensity, in a suit.

Great article, very entertaining. I played the 10th with my current (very amateur) orchestra a few years ago, and I remember that section well. Did we manage it? No comment.

I hear you about the slow movements though… Our last concert included Dvorak’s 9th and the 4th mvt from Mahler’s 5th… You can guess which was harder to pull off.

Oh and I’ve been playing for about 25 years now (eep!) and I hadn’t a clue what an 8th is… I’m guessing it’s what the rest of the world knows as a quaver?

Thanks for reading, and commenting, Hugh. I laughed at your last sentence- very UK-centric. Indeed, a quaver and and 8th note are the same thing. The non-UK system is really more logical because it is all mathematical and doesn’t become silly when you have do deal with things like 64th notes (who has time to say hemi-demi-semi-quaver in a rehearsal!), but I have learned the UK system and use it when I work here. Funnily, many of my British friends who have lived in America don’t go back to the UK system when they work here- they prefer the US terminology…