Welcome to a special edition of Explore the Score. I’ve told friends for years that some day I wanted to write a book about Shostakovich 5. Here’s the short version.

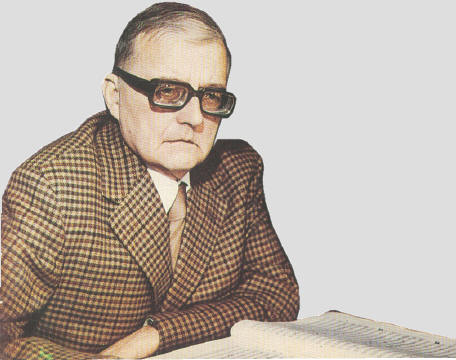

Dmitri Shostakovich- Symphony no. 5 in D minor opus 47

Genesis

Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony would, at first glance, seem, on purely musical grounds, to be a most unlikely work to have become possibly the most hotly debated and discussed piece of classical music written in the 20th c.. Nonetheless, in the three quarters of a century since it was composed, it has never failed to divide opinion or inspire debate. It remains one of the few pieces of music that can still incite angry exchanges among performers or musicologists who have come to sharply divided conclusions about its importance, its originality and whether it ends in “triumph” or “forced rejoicing,” or, to put it simply, whether it has a happy or sad ending.

The piece was conceived under the most intense spotlight imaginable. Josef Stalin’s public denunciation of Shostakovich’s opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk in the essay “Muddle instead of Music” published in Pravda on the 28th of January,1936 had effectively turned Shostakovich into a strange combination of a non-person and “musical public enemy number one.” Shostakovich’s denunciation could not have come at a worse time- it was the very peak of the Stalinist Terror, and Shostakovich knew as soon as he saw the editorial that the lives of both he and his family were in grave danger. Artistically, this blow came at a terrible moment for the coposer. A former wunderkind who had become instantly world-famous when he published his First Symphony at the age of 19, by 1936, when “Muddle” was published, Shostakovich was a composer at the peak of his powers and early maturity, possessed of a breadth of experience to match his talent, and with his confidence in full flower. Lady Macbeth is a work of staggering inspiration and consummate skill, and he had already completed most of his next major work, his Fourth Symphony.

A starkly tragic masterpiece, Shostakovich’s Fourth Symphony was one of his most ambitious and innovative works. It shows him breaking radical new ground as a post-Mahlerian symphonist, and so it is no surprise that friends and colleagues implored Shostakovich to withdraw the work before its scheduled premiere after Stalin’s rejection of Lady MacBeth. Its dark message and comparatively modern language would have, in all likelihood, sealed Shostakovich’s fate with the authorities. Canceling its premiere was one of the most painful decisions of Shostakovich’s professional life.

Shortly after the Pravda article was published, Shostakovich was summoned to a meeting with Stalin’s emissary, Platon Kerzhentsev. Shostakovich was asked whether he “fully accepted the criticism of his work” in the Pravda articles. Shostakovich’s answer, according to Kerzhentsev was that “he accepts most of it, but he has not fully comprehended it all.” Shostakovich’s vague answer had been carefully calculated, but was a huge risk- had he fully accepted all the criticisms, his future music would have been judged strictly by the terms of Stalin’s previous criticisms. By feigning ignorance, he was giving himself vital space to continue to create and experiment, but had Stalin sensed his reticence to comply fully, the price would surely have meant death for Shostakovich and his family.

Under the circumstances, Shostakovich could have been forgiven for avoiding the most public of instrumental genres, the symphony, until the climate had improved. In fact, he would later do exactly that- in the late 1940’s when the premiere of his Ninth Symphony led to another public shaming by the authorities, he chose to wait until after the death of Joseph Stalin four years later to complete his Tenth Symphony, even though parts of it were sketched many years earlier.

Reception

However, in spite of the danger of further provoking the Party, Shostakovich quickly began work on the Fifth, completing the score in July 1937. The work’s premiere by the St Petersburg (then the Leningrad) Philharmonic under its music director, Yevgeny Mravinsky, was an occasion of incredible expectation and almost unimaginable anxiety. The impact of the work on its first audience is hard to overstate- many listeners wept openly during the elegiac slow movement. At the end of the performance, the audience burst into an ovation so passionate and stormy that it nearly eclipsed the 45 minute symphony in duration.

Shostakovich’s public statements were a vital tool in his life-long cat and mouse game with the authorities. As a result, one should always read anything he wrote or said about his music with great scepticism- his audience was the Party, not posterity. Shortly after the premiere, Shostakovich published a short, highly opaque essay called “My Creative Response,” from which comes the Fifth’s epigraph ‘A Soviet artist’s practical, creative reply to just criticism.’ This title and the work’s traditional formal structure and direct musical language served to placate Stalin and the Party. Shostakovich was partially rehabilitated and the piece went on to become one of the most frequently played works in the twentieth century. Shostakovich’s contrite essay, and the official verdict of party-approved critics, especially Alexei Tolstoy, helped set in place an official programme for the work as “an optimistic tragedy” that would allow it to be exploited by the state, as well as performed, but this official reading, which was never accepted by a majority of Russian musicians or listeners, came to be uncritically accepted by many Western commentators, leading to decades of confusion, misunderstanding, and even misrepresentation.

Early critical reaction unanimously recognized the deeply tragic mood of the first three movements. One writer noted that “the emotional tension is at the limit: another step—and everything will burst into a physiological howl.” Another said, “The passion of suffering in several places is brought to a naturalistic screaming and howling. In some episodes, the music can elicit an almost physical sense of pain.” Given the later-day controversy about the meaning of the Symphony’s Finale, it is worth noting that the writer Alexander Fadeyev wrote after the premiere that “The end does not sound like an exit (and certainly not like a triumph or victory) but like a punishment or a revenge on someone.” Another listener compared the work with Tchaikovsky’s Pathetique, the most tragic of all Russian symphonies.

First movement- Moderato

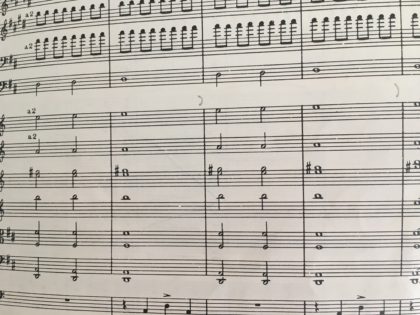

It seems there is a tradition in the best fifth symphonies from Beethoven to Mahler to begin with a shocking, dramatic gesture. The almost physical impact of the beginning of Shostakovich’s Fifth slightly belies how restrained he is in using the orchestra in the Symphony’s opening paragraphs. As in his Eighth and Tenth symphonies, he begins using only the strings, gradually introducing the bassoons, flutes, oboes and clarinets, and finally, the brass and percussion.

In the late 1970’s, the publication of Solomon Volkov’s “Testimony- The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich” brought on heated debate in the West over the official programme of the Fifth. A mirror-image programme, no doubt closer to the truth but still far too one-dimensional, was suggested: that the work was a protest against the Stalinist Terror. In the ensuing decades of often maddeningly reductionist debate, it has been easy to overlook evidence that the work has several programmes. The first of these is suggested by the first movement’s second theme. Soaring and tender in its first incarnation in the violins, and more pained when repeated by the violas, playing in an intentionally cruel register, it is a variation of the work’s opening theme, but also a quote from the Habanera (“L’amour, l’amour”) of Bizet’s Carmen.

Why Carmen? In 1934-5 Shostakovich had fallen in love with Elena Konstantinovskya. She had ultimately rejected him, and married a man named Roman Carmen. As with his symphonic idol, Mahler, Shostakovich understood that a symphony could carry a variety of messages and express a range of programmes, from the most public to the most private. This first movement of the Fifth marks an important turning point in his development, wherein he defines and perfects his own, very personal reworking of traditional Sonata form. By reversing the order of themes in the recapitulation, he creates a vast arch form, building in intensity to a climax of apocalyptic intensity, finally disintegrating into tragic resignation. The restraint with which the movement begins and ends is matched by the near hysterical abandon of the movement’s climax. Shostakovich uses tempo to intensify this arch shape, beginning the symphony very slowly, gradually speeding up through the development and then winding down to end at very nearly the same speed as the opening. This design was based to a large extent on the first movement of Tchaikovsky’s Pathetique Symphony, and Shostakovich would use it again in the 7th, 8th and 10th symphonies.

Second Movement- Allegretto

The second movement, a rather gruff Ländler shows Shostakovich at his most Mahlerian- mixing charm and venom, elegance and irony in equal measure. The Trio begins as a study in obsequious grace, with the solo violin playing flirtatiously over delicate harp and pizzicato accompaniment, but the music repeatedly loses its cool, descending into noisy violence. The sinister return of the Ländler is surely a nod to the Scherzo of Beethoven’s Fifth, with its skeletal instrumentation of staccato bassoons and pizzicato strings. One last flirtatious nod to the violin solo, this time on solo oboe, disingenuously promises a gentle resolution of the movement’s tensions, before a final angry outburst brings the movement to an abrupt close in A minor.

Third Movement- Largo

The extraordinary Largo, written in just three days, is one of Shostakovich’s most moving creations. As in the opening of the first movement, Shostakovich uses the orchestra with tremendous restraint. Again, he opens with a long paragraph for strings, only gradually and sparingly introducing woodwinds and percussion. The brass remain silent throughout. In the second paragraph solo oboe, clarinet and flute each state a theme pregnant with loneliness over nearly static string tremolo accompaniment. Then, Shostakovich begins the inexorable build up to the anguished emotional climax of the entire symphony, a passage the great American musicologist Michael Steinberg calls “the most Tchaikovskian page in all Shostakovich.”

Finale- Allegro non troppo

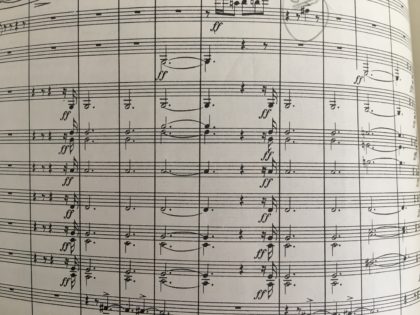

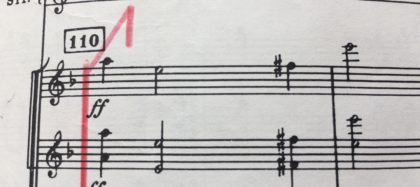

A dispassionate glance at the score of the Finale, a movement described by Volkov as “perhaps the most disturbing and ambivalent music of the 20th c.” immediately reveals an important structural tie to the first movement. Once again, Shostakovich’s metronome markings express a carefully calculated arch form, beginning at crotchet= 88, then speeding up through 104, 108, 120, 126, 132 to 184, then winding down from 160 to 108, 116 and finally 92, exactly (as in the first movement) one notch above the opening tempo on the metronome, but for one important quirk. Where as in the first movement Shostakovich marks the opening tempo as quaver=76 (the equivalent of crotchet=38) and the end as crotchet=42 (or the equivalent of quaver=84). In the finale, this is reversed, and instead of ending with a marking of crotchet= 92, the final tempo is quaver=188, a marking that on first glance seems eccentric enough to merit suspicion. In spite of this clear structural tempo relationship, Michael Steinberg points out that “Most of the big-name conductors seem to proceed entirely at random.”

The Finale shatters the rapt stillness of the Largo with a violent and brutish march, the theme of which integrates material from no less than three sources. The first is, again, Carmen, using the music from the Habanera setting the words “Prends garde a tois!” or “Beware! Beware!” Secondly, material from the theme was used again in Shostakovich’s later setting of Robert Burns poem “MacPherson’s Farewell,’ to the words “Sae rantingly, sae wantonly, sae dauntingly gaed he” as the hero is led to “the gallers-tree.” Finally, as Gerald McBurney observed, the first four notes (A D E F) are the same as the first four notes of Shostakovich’s 1936 setting of the Pushkin poem “Rebirth,” wherein the poet describes “A Barbarian artist with sleepy brush”, who “Blackens over a picture of genius.” The parallels with Stalin’s obliteration of Shostakovich’s Fourth Symphony and Lady Macbeth are obvious.

In the course of the ensuing build up, there are more quotations to be found, notably from the fourth movement of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique and Strauss’s Till Eulenspiegel (*), both of which, like Shostakovich’s Burns setting, contain vivid musical descriptions of public executions. In the quiet middle section, Shostakovich returns to his setting of Pushkin’s “Rebirth” quoting his own music from the final stanzas:

But with the year, the alien paints

Flake off like old scales;

The creation of genius appears before us

In its former beauty.

Thus do delusions fall away

From my worn-out soul

And there spring up within it

Visions of original, pure days.

Confusion over the metaphysical and political “meaning” of the Fifth has been greatly increased by the purely musical confusion over the final tempo, largely propagated by Leonard Bernstein’s iconic 1959 recording and his performance with the New York Philharmonic in Shostakovich’s presence that year, in which he famously more than doubled the speed from what Shostakovich had written. Although Shostakovich later repeatedly confirmed his intention that it be played at quaver=188, confusion continues to this day among conductors and critics more inclined to learn a piece through recordings than through the score. (In his defence, Bernstein, throughout his career, was generally more scrupulous in his observance of many of the other metronome markings in the symphony than Mravinsky, who tends to speed through the symphony’s slow music).

But what are we to make of that idiosyncratic metronome marking? By giving the tempo in quavers, Shostakovich is implying that each quaver has its own impulse, its own emphasis, and, in fact the entire coda has an absolutely unremitting string of continuous quavers, all on the pitch A, 252 in all. The brass, in note values double their original length, bring back the opening “Barbarian” or Carmen theme, now in triumphant D major- “Prends garde! Beware!” it seems to bellow over and over. Through it all, the strings, woodwinds and piano continue to repeat those A’s over and over. When asked by his son what all those A’s where meant to signify, Shostakovich reportedly said “La! La! La! La!” La is the Russian nickname for Elena, the woman who had broken his heart by marrying Mr Carmen; Shostakovich’s archivist Manashir Yakubov calls it “a cry of despair and farewell.” Yet, asked by another friend, Shostakovich replied “Ya! Ya! Ya!” or “Me! Me! Me!” This tension between the barbarian and the genius, and between “me” and “her” continues to the final note of the piece. Ambivalent, angry, triumphant, tortured, heartbroken, defiant, world-embracing and self-regarding, the final page of this greatest of 20th c. symphonies is so powerful for much the same reason it has always been so controversial. When one is able to recognize the depth and intensity of its countless tensions and contradictions, what listener could ever settle for something as simplistic and straightforward as a happy, or sad, ending again?

* Volkov, Solomon – Shostakovich and Stalin, p. 178. 2004 Little Brown Publications, a division of Time Warner Group

A note on the references here to Berlioz and Strauss, which I’ve been asked about many times here. These come from Volkov’s book (not Testimony) cited above. “Scholars are finding hiddent quotations now in the finale from passages in Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique and Richard Strauss’s Till Eulenpiegel.” Volkov does not cite which scholars, or say exactly which places he or they are referring to, but the passage in his book is exceptionally spot on, carefully referencing the song quotations to MacPherson’s Farewell, Renaissance, etc.

I think it is likely that the Till reference refers to the brass chords at the end of the symphony, which are similar to the brass chords at Till’s execution scene in the Strauss

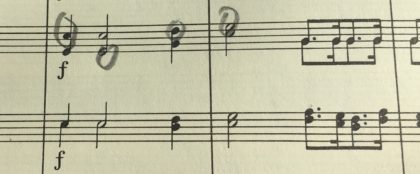

I think it’s likely the reference to the Berlioz is the March to the Scaffold, in which the main theme has the same rhythmic contour as the Shostakovich, and if you pick and chose from the two voices, the similarity is much clearer:

The rising 3 steps of the theme of the Berlioz is also consistent with the main theme of the finale of the Shostakovich.

Copyrighted material is partially reproduced here without profit for educational purposes only, under relevant Fair Use provisions of international copyright law and will be removed on request.

I take it you feel the quotations support the “Testimony” interpretation strongly enough that you didn’t feel the need to question its validity here? The greatest argument I’ve heard in favor of a triumphant ending is that “Testimony” was very possibly fabricated by Volkov (or at least skewed) in an effort to reimagine Shostakovich after his death. That said, I’ve always remained firmly in the (simplistically-rendered) “tragic/sarcastic” camp, and I’m heartened to see I’m in good company. I’m definitely saving a copy of this essay; Shosty 5 is on my Top Ten list of things I want to conduct someday, somehow (so is #10).

You tease, now I want to read the whole of your book not just the excerpt (and the joke with the images was funny in a way)!

At first I would’ve argued that A D E F is a simple enough tune which can be found in way too many places in music, but the connection to Carmen and “Rebirth” is made elsewhere in the symphony and/or finale as well, so it does allow Shostakovich to use it for great effect as an allusion as well (in any case, the ADEF-connection was new to me).

Can you point to the Symphonie Fantastique and Till Eulenspiegel quotes in the score? I don’t think I’ve heard about these two until now.

To those who haven’t heard it yet: the Discovering Music programme on BBC3 is a good source of analysis through audio samples.

@Mikko Utevsky

Hi Mikko- I purposefully avoided Testimony in this because it tends to be a conversation stopper, but let me answer your question by re-phrasing it. Rather than the quotations supporting a Testimony interpretation, I think that Testimony probably reinforces an interpretation that reflects what is in the score. After all, either side in the Testimony debate could find a smoking gun that proves or disproves their case. On the other hand, the quotes are there (Shostakovich uses quotation like few composers who ever lived- it’s one of the hallmarks of his style) in the score. Nothing to do with Volkov. The metronome markings are there. Nothing to do with Volkov. What has confused the issue is that so many conductors learn the piece from other conductors rather than from the score. This is one piece where we should avoid “interpretation” and go for “realization” and let the music speak for itself, in all its contradictions, with all of its intensity.

I’m not sure what I like most – the article itself or the file name of your link to the viola extract “Cruel-to-Violas.mp3”

Much as I love Bernstein for giving us WSS and On The Town, it hurts me that he and other people since have taken the coda at that speed

At least he did it out of love. The rest of his interpretation is wonderful- he digs a lot deeper than some of his Russian colleagues in the slow movement. If it weren’t for the coda and the nanny-goat-vibrato flute playing, it would be one of my favorite performances

Agreed. I love his tempo of the beginning of the Finale. It’s so much more exciting like that. Admittedly I’m speaking as a player who gets an insane adrenaline rush from playing it at that tempo…..

Out of interest, btw, what’s your performance tempo for the coda? A precise adherence to Shostakovich’s tempo or a personal choice?

‎(also how about Petrenko’s recording – the exciting opening without the Lenny B ending!)

I think it’s really important to respect the arch form with the tempi- it’s got to begin and end slowly. I haven’t heard Petrenko’s recording yet. Hard to imagine liking a modern performance that doesn’t try to do justice to what I think is a pretty interesting concept on the part of a pretty damn good composer…

Bernstein starts the last movement too fast, but he does try, with some success, to keep ratcheting up the tempo, although on that NYPO recording, there are places were the orchestra slows down because they can’t quite maintain the frenetic pace between tempo changes. Still, at least it has the same basic logic. At the end, he’s going completely in the wrong direction- speeding up when the music should be slowing down.

I love the fast speed at the end, and the last time I conducted it tried to get it like Bernstein’s. (Whilst making sure that the orchestra knew that this was my personal taste and that this was not the generally accepted speed.)

Hi Lawrence- Wouldn’t you say that the question is not whether it’s the generally accepted speed, but whether it’s the composer’s intended speed that is important?

Yes, and I made that point to the orchestra (my youth orchestra) too, but I find Bernstein’s speed so exciting and different from any other version I know that I couldn’t stop myself!

I’m curious as to what recording I should turn to for a strict adherence to the proper tempos of the last movement? I would assume Mravinsky, but you mentioned that there are parts that he rushes as well . . .

Hi Damon

I’ve long since lost my notes from when I tempo checked everyone about 8 years ago, but the Russians tend to be closest in the last mvt to the markings. Maxim’s later recordings are pretty close, and Rostropovich was pretty good (I think he errs on the side of slower-than-marked at the end). Temirkanov very good, too. It’s most fun to check them yourself- there’s a great iPhone app called BPM or Beats Per Minute, where you can tap the beats of whatever you’re listening to and it tells you the exact tempo. Check it out!

Does anybody know why he changed the tempo in the final section of the 4th movement, fig.131 from the first edition of 1939 (quarter = 188) to eigth = 184 in1947/56 editions which was changed back again in the 1961 edition and used in the 1980 collected works. What a minefield

For some reason the Fifth Symphony has been running through my head the last few days while I battled the flu.

Does anyone remember an RCA (?) recording of the Fifth from some time back in the fifties that credited an arranger? A little research provides the name of the “arranger” as Howard Sheldon, whom I believe was a big deal in publishing at the time. I had the record when I was a kid and listened to it constantly, and for better or worse it became my frame of reference for the piece. Imagine my surprise some years later actually playing through the work (I was a double bassist at university) and discovering that the edition we played wasn’t the same as the edition National Symphony played! Horrors!

Specifically, in the finale, somebody (Sheldon, presumably) doubled the length of the last chord before the final resolution. If you can’t picture it, try this–the last tension chord usually has four timp hits, now try to imagine it as eight.

Anyways, this discrepancy has either scarred or enriched my life or both depending, and there seems to be no evidence of it anywhere on the interwebs.

Hi there. Great article.

Just wondering, as I tackle all this for he first time, has anyone ever questioned the mm at the opening of the symphony?

Moderato is hard to reconcile with quaver 76. Crotchet 76 would be quite hasty, but still fits with your tempo-arch structure, and still sounds like Shostakovich. For what it’s worth, in the piano concerto op 35 he writes a moderato at crotchet 84 in the first mvt, a moderato at crotchet 108 in the 3rd mvt. Crotchet 76 in the 2nd mvt is lento.

Any thoughts?

I’m not suggesting that shost couldn’t tell his crotchets from his quavers, but still…

Hi Paul

Great to hear from you.

Many have ignored that metronome marking, and it is very slow at that speed (I seem to remember Wigglesworth is one of the few who sticks stubbornly to it), but I don’t think there’s any evidence it is a typo. I believe one of the sources has a second marking in the fourth bar of “Poco piu mosso, quaver=84” To me, this makes perfect sense if you look at the last section starting at fig 44 where he repeats the material from these bars in inversion. The tempo there is crotchet= 42, which would be the same as the quaver=84 when we first heard this material. It also makes me wonder if maybe he wasn’t all that worried about whether one is in 8 or 4…

Cheers

Ken

Yes that makes good sense. (Unless he meant minim 42!!)

Moderato is such a strange marking for something so static.

One of the amazing things about DS is how often the same material works equally well at different speeds – eg after 25 and at 32.

Great article, thanks very much. But again, could you point to the Berlioz and Strauss quotes? would be great to nail those

I read somewhere that it quotes Boris Godunov (with the people being forced to bow to the Tsar) somewhere in the 4th movement, but it wasn’t specific where or how- do you know anything about this? I’ve just spent a night looking for fun facts and I’m interested to know.

Ps. hahahaha the Bernstein massacre…

Great article, fascinating. One question about the famous quaver 188 – all the other markings in the symphony are actual metronome markings if I remember correctly – that is, if we look at a classic metronome, we see 80-84-88-92, and then of course 160-168-176-184, not 188. So one option is, the last 8 is wrong, and should be 184. What else has an 8? 168, 138, 108, and 88. Well, 88 is the start tempo, both in quarters, we end where we started exactly half tempo. In the first movement, there is no double-time relation so to speak, the pulse is the same at the beginning and end, differing by a few clicks (and maybe his lowest metronome possibility was 42?)

Personally, I am more curious about what the numbers imply – what is the character, where does the sound speak? Can a brass section truly sustain it? (I believe this is why there is such a wide range of tempi at the end, people look at it and say – he can’t possibly mean that slow). To me, there should be some relation, either same speed as you start, or twice as slow. To me, I like the latter, we have quavers going into the final tempo, and suddenly “jerking” to go faster or slower makes no sense.

Great article, excellent insights.

Hi Kenneth. I’m doing it at the moment, and only last night the first horn player came up to me to complain that one of my tempi in the last movement was too slow. “I’ve played it loads of times”, he said, “and listened to loads of records. They all do it faster”. “But the score”, I said, and showed him. He wasn’t convinced. All those other conductors spoke with more authority than Shostakovich. Sigh.

It seems I have run across a very interesting page on my smart phone. Conductors and talented players talking about the importance of pacing a great piece of music. To thyself be true. I love and admire classical orchestras. You bring to us who listen a great joy to our lives. I bought a ticket to hear my first shostakovich in person. One of my favorites the #5. The conductor gustavo dudamel and the los angeles symphony. Located in los angeles at the fantastic looking walt disney concert hall. I love the upper mid balcony for its great sound and detail. I know it will sound just great. MY first visit there. from what I have heard about dudamel l know he can.handle this great piece of work with all the right pace and strength of emotion needed for such a beautiful symphony. at home I love my CD #5 version by the Cleveland orchestra on telarc maazel conducting. love reading your page. music listener.

Hello, thanks for the great articles, one of the best analysis of this masterpiece that I’ve found. I was wondering about the Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique and Strauss’s Till Eulenspiege quotes that you mention. As much as I looked into the score I can’t find them. Could you mention the numbers of the scoresheet where they happen?

Best,

Pablo.

Hello Maestro,

Could you clarify where it is that you have found the Berlioz and Strauss quotes in the finale? I have looked through the score and numerous musicological sources and I’ve not been able to confirm the location of these specific quotations.

Thanks you

Am I mistaken, or have I seen a recording of No5 conducted by the composers son somewhere?

Yes. I grew up with that recording. My parents bought it for me when I was four after I heard part of it at a children’s concert.

Thank you for this, Kenneth. My favourite symphony to play (as a cellist) and to conduct – although it has to be said, it tears me to shreds every time. Unbelievably profound.

The controversy about the Shostakovich/Volkov “Testimony” was settled for me when the Boston Symphony played Shostakovich Sym 10 in November 1990. I was bass trombonist of the BSO from 1985-2012 and Kurt Sanderling was a frequent guest conductor of the orchestra. We performed two Shostakovich symphonies under his baton, Sam 15 in January 1988 and Sym 10 in November 1990. Sanderling knew Shostakovich intimately, had a well-documented personal friendship and professional relationship with the composers, and conducted many of his symphonies with the Leningrad SO and other orchestras. At rehearsals with the BSO for Sym 10, Sanderling spoke at length about “Testimony,” that he was there when many of the events in it were described, and that he said without equivocation that Volkov’s book is an accurate portrayal of the world in which Shostakovich worked and lived and how Shostakovich himself felt about certain events – many of which he had personally related to Sanderling. Sanderling was impatient by the assertion that many musicologists made that Volkov somehow fabricated the book.

On November 7, 1990, at the intermission of a rehearsal, I approached Sanderling and told him I was taken by his comments about Shostakovich, Volkov, and “Testimony,” and I asked if he would sign my copy of the book. He did. I cannot upload a scan of the title page to this blog but this is what he wrote:

=====

It is true!

Kurt Sanderling

(November 7, 1990)

=====

It’s not only in the countertheme of the opening movement that we hear references to the Habañera from Bizet’s Carmen. Consider the four notes that open the final movement, the same four notes that form the main theme of the coda. Shorten the first note and we have the dance tune from same source. I wonder if Elena Konstantinovskya ever had a clue to the musical encoding she inspired!

— Louis

“It seems there is a tradition in the best fifth symphonies from Beethoven to Mahler to begin with a shocking, dramatic gesture.”

Perhaps an exception is Vaughan Williams Symphony 5?

I knew nothing of the Bernstein controversy but it is particularly shocking as I only came across this wonderful analysis while trying to track down a half remembered comment about the last movement from a sleeve note. It described the final march theme as ‘We will be happy, we will be happy” intoned through clenched teeth, which seemed to capture the mock triumphalism that would surely be completely undermined by an increase in tempo.

‘“It seems there is a tradition in the best fifth symphonies from Beethoven to Mahler to begin with a shocking, dramatic gesture.â€

Perhaps an exception is Vaughan Williams Symphony 5?’

Perhaps RVW 5 is not an exception. After all it starts with a pedal-point on C, a note which is completely foreign to the opening tonality of D.

Shostakovich 5 on a children’s concert? Shouldn’t this work be at least PG-13 for intensity?

It was an open rehearsal, not a concert. Thanks!

I’ve been intrigued by your comments over the years on Bernstein’s tempi for Shostakovich 5 finale (only heard it once, many years ago). Pursuant to Peter Wadl’s comment above–Bernstein’s score is viewable at NYPhil’s digital archives. At fig. 131 what is printed in the score is crochet (not quaver) =188. Bernstein’s annotation there (from what year?) is minim=96, only slightly faster. So arguably he was ‘obeying the score,’ at least the score that was in front of him.

His real double-speed-up is at Fig 121, where he crossed out the printed crochet (=100-108) and substituted minim. At 128, crossed out printed crochet=116 and wrote in crochet=144.

Douglas Yeo, thank you so very very much for your comments regarding “Testimony”. I admit I have always been a true believer, but it warms my heart to hear your experience. Thank you!