Cellist Antonio Meneses and the Northern Sinfonia have just made a stunning recording of Elgar and Gal’s cello concerti with his longtime friend and collaborator, conductor Claudio Cruz. Although I wasn’t involved in the recording, Avie Records asked me to write the liner notes for the CD, which I was very happy to do. The upshot of this project is that we’re very happy to present expanded versions of the Gal and Elgar essays as special Explore the Score features, including clips from Antonio’s new CD, due out in June. Today, we start with Elgar.

____________________________________________________________

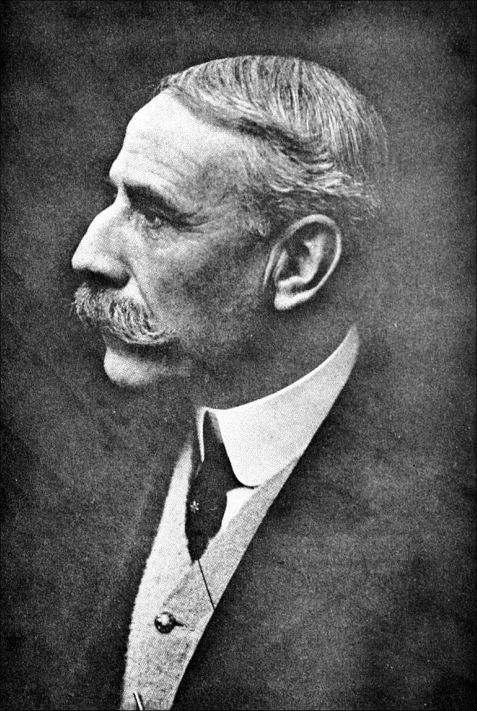

Composers who become cultural icons in their own lifetimes often have complex, fraught and paradoxical relationships to the societies which celebrate them and venerate their work. Edward Elgar is certainly a case in point. He was born the quintessential outsider- poor and Catholic, self-taught as a composer, and a man who felt most at home in the backwaters of Worcester and Hereford, rather than in Establishment London. Nonetheless, he rose to become a central cultural figure, an icon of the establishment and Master of the Kings Musik. His music was the embodiment of Edwardian pomp and imperial grandeur. Elgar’s public persona became so completely that of the perfect upper-class English gentleman that in retrospect it seems to border on self-parody. In private, however, this prince of British musical life could be eccentric, vulnerable and moody. He could also be deeply ambivalent about British culture and English music. In his lecture series “A Future for English Music,” given in 1905-6, Elgar struck a skeptical, even critical tone: “An Englishman will take you in a large room, beautifully proportioned, and will point out to you that it is white—all over white—and somebody will say what exquisite taste. You know in your own mind, in your own soul, that it is not taste at all—that it is the want of taste—that it is mere evasion. English music is white, and evades everything”

In spite of these contradictions, Elgar wore the mask of the proper Edwardian gentleman with complete commitment and not a hint of irony, and he was deeply affected by the unravelling of the Imperial order he had come of age in. He seemed to need to keep both sides of his personality in balance, to be both insider and outsider, Establishment icon and bohemian rebel. This polarity can be seen throughout his creative life- there are few more grandiose and public pages of music than the close of the Enigma Variations, yet the piece is, at its heart, a very private collection of miniatures. Michael Steinberg noted that First Symphony begins with “a great “imperial” tune” which triumphs “only by the skin of its teeth,” but in other works, “triumph is not in the picture at all.”

Elgar’s two concerti embody this conflict between public and private man perhaps most elegantly, and in very different ways. The Violin Concerto, written in 1910, is an epic work, symphonic in scope and idiom. Both the solo and orchestral writing are conceived on the grandest possible scale. Yet, the work is, at its heart, desperately personal- a confession of private longing and moral torment, in which the cadenza, normally the high point of virtuoso showmanship, becomes instead a moment of heartbreaking intimacy and fragility.

Written in the summer of 1919, the Cello Concerto embodies this conflict between public and private man in a new way. Adrian Boult, Elgar’s greatest interpreter, noted the Cello Concerto “struck a new kind of music, with a more economical line, terser in every way.” Although written in four movements rather than the traditional three of the Violin Concerto, it is considerably shorter- most performances come in well under 30 minutes, compared to, for example 58 for Nigel Kennedy’s famous, but unusually broad reading of the Violin Concerto.

It is in the first three movements that this “new kind of music” is most obviously present. Gone are the rich, Romantic textures and the grand orchestral tuttis of the Violin Concerto- the “big” tutti in the first movement of the Cello Concerto is only 6 bars long, and instead of a long, grand orchestral introduction, the work opens with a recitative for the solo cellist. This iconic opening was something Elgar worked at extensively- in the sketch it was a bar longer, and he experimented with placement of orchestral punctuation. The main theme of the following Moderato was one the composer closely identified with. On his deathbed, Elgar “rather feebly” tried to whistle the theme to his friend, the violinist William Reed. “Billy,” he said with tears in his eyes, “if ever you’re walking on the Malvern Hills and hear that, don’t be frightened. It’s only me.” The Cello Concerto has been a gateway to Elgar’s music for countless listeners, and its popularity makes it hard to fully appreciate what a departure this theme was from anything in his previous works. Its modal character, now considered quintessentially English, is something we associate more with Vaughan Williams than with Elgar, and the stark simplicity with which he introduces it, first with the viola section alone, the solo cello only sparsely accompanied, is typical of this new, terser and more economical way of composing.

The first movement ends with desolation rather than catharsis, with the cello carrying the tune down to a low E’, which is then held through to the next movement by the orchestral celli and basses. The Moderato is linked to the Scherzo by a mercurial accompanied recitative, in which the moods swing precipitously between extremes of wit, tenderness and violence. Elgar’s decision to include a Scherzo is inspired- it gives this most intimate of concerti an element of virtuoso display, while maintaining its lean and understated character. It’s possible he got the idea from Brahms’ Second Piano Concerto, but Elgar’s concise approach shows how much he had moved on from the influence of one of his heroes.

The private character of the work deepens in the Adagio. Elgar’s metronome marking of quaver=50 ought to be ample warning to cellists would turn it in a late-Romantic dirge, but he was just as emphatic that the movement not be rushed. In his own recording of the work, the extraordinary cellist Beatrice Harrison can be heard pressing impetuously ahead, but Elgar, a fine enough conductor to succeed Richter as director of the LSO, stubbornly tries to hold to the main tempo. Michael Steinberg rightly underlines this movement’s “Schumann-esque qualities,” and Elgar knew that a certain element of understatement would make it all the more moving. His publisher, Novello, recognized the potential appeal of this movement when he first received the score, and asked Elgar to compose a concert ending for stand-alone performance, since in the Concerto the movement ends on the dominant. Elgar tried to accommodate, but finally wrote back, saying “I fear I cannot think of another ending for the slow movement- it will do as it is…”

In the fourth movement, Elgar seems determined to re-assert his public persona. The orchestral writing is far more symphonic and the cello writing more declamatory than in the rest of the piece. The brusque, aggressive tone of the opening is a shocking contrast from the tenderness of the Adagio, and there are harmonic shocks as well, as in just 8 bars, Elgar moves from B-flat minor to E minor. There follows yet another recitative, this one more determined and extrovert than those in the first two movements. This attitude of determination continues in the main Allegro, man non troppo which follows, as Elgar implores the soloist to play “risoluto.” The main mood for the bulk of the movement is one of heroic struggle, similar to the Finale of his First Symphony, the work which marked the apex of his career. However, instead of the hard –won triumph which ends the earlier work, in the last pages of the Cello Concerto the public rhetoric abruptly evaporates, and there follows what may be the most moving page in the cello literature.

Elgar’s own place in British musical life had been eroding since the premiere of his Second Symphony in 1911. By 1919, he was painfully aware that many considered him yesterday’s man. He had also been deeply affected by the Great War, and had largely lost the urge to compose between the completion of Falstaff in 1913 and the last great surge of creative energy in 1918-9 which gave us the String Quartet, Violin Sonata and Piano Quartet, as well as the Cello Concerto. After this last burst of inspiration, he attempted nothing on a similar scale until beginning work on a Third Symphony in 1932. Whether he intended it to be so or not, this last page was, in many ways, his farewell. In comparison to the draft of the rest of the work, according to John Pickard, here “even the handwriting reveals something of the emotional excitement under which the music was written.”

All his career, Elgar had jumped nimbly between his public and private worlds. Now, it is as if he forces the public Elgar to remove the mask of Edwardian rectitude while standing in the public eye. The outpouring of longing and vulnerability which follows makes this one of the most touching passages in any work. Once all has been said, and all has been revealed, Elgar abruptly takes up his Colonel Blimp disguise, but the listener now knows what effort it must have taken to create the mask his culture had come to expect him to wear.

c. 2012 Kenneth Woods

Recent Comments