Maybe it is because I’m more or less at the mid-point of a Brahms cycle with the Surrey Mozart players, but right now, I feel like I’m orbiting planet Brahms. 2012 is looking like a Brahms year for Ken, and I like that a lot.

I’ve been accumulating some morsels of Brahmsian prejudice that I’ve wanted to share here.

1- I really don’t like the Schoenberg arrangement of the opus 25 no. 1 Piano Quartet. I like Schoenberg. I like the G minor Piano Quartet. I like Schoenberg’s arrangements of the Emperor Waltz and Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, but I’ve never warmed to what Schoenberg reputedly called Brahms’s Symphony no. 5. I heard it again on the radio last week, and what really annoyed me was that maybe 30% of it sounds like vintage Brahms, %20 of it sounds like someone trying to imitate Brahms and not managing it, and %50 percent of it sounds like Schoenberg’s take on Brahms. I’d far rather it sound 100% unidiomatic and totally like Schoenberg, but the seesawing back and forth between styles really bothers me. It’s such an epic piece, and the inconsistent approach to the orchestration seems to carve it up into little chunks. I think the arrangement is also exhibit A in why Brahms is the 2nd most underrated orchestrator ever, after Schumann. It’s not that people think Brahms is a bad orchestrator (a charge often erroneously leveled by fools at the great Bobby Schumann), it’s just they don’t think of him as an orchestrator, yet his orchestration is incredibly personal and hard to replicate. At least Schoenberg seemed to find it hard. It always engages the musicians and always serves the music.

2- Speaking of hubris- on the shelf in my office is a nearly finished orchestration of the Brahms A major Piano Quartet, opus 25 no. 2. In spite of my inability to warm to Schoenberg’s arrangement of the G minor, and in full realization of the fact that Schoenberg was a genius and I’m, at best, a hack, a few years ago I felt a sudden, overpowering impulse to orchestrate the A major. I was coaching an amateur group on the piece and, in trying to help the pianist conceptualize the sound and articulation for the beginning, I suddenly heard that opening orchestrated in a very specific way. I was so struck by the sound of it in my head that I had to sit down and sketch out an orchestral version of the whole piece. Some of the pianistic writing gave me fits, which is why I haven’t finished it, but I’m so desperate to hear the opening that I will have to finish the whole thing this summer.

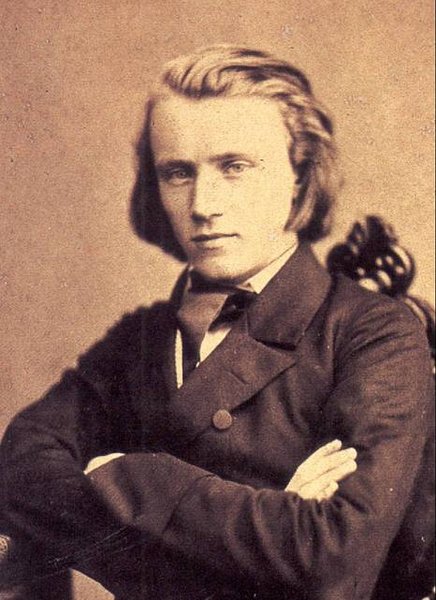

3- Speaking of the G minor Piano Quartet- When I was first learning the piece, I was baffled by a passage in the first movement for violin and viola in unison. It’s in a funny range for both of them, and, in addition to being hard to tune, the overtones rang in a very strange way. It always bothered me- I couldn’t figure out why on earth Brahms had doubled the part. Then, one night, I dreamed I was sat on a bench in Central Park (I was living in Wisconsin at the time), when Brahms himself (young, dashing Brahms, not big bearded Brahms) sat down next to me. We exchanged a bit of small talk and then he asked me if I was enjoying working on his Piano Quartet. I told him I was absolutely loving it, but that I did find that one passage perplexing. “Herr Ken,” he said,” My intention in zis passage was to evoke ze sound of the horn, which I thought would best suit ze broad character of ze tema. I think if zey balance their parts correctly, it should have zis effect.” The next morning in rehearsal, I suggested to my colleagues that they might try to aim for a more horn-like sound in that passage. It sounded GREAT. Later, at the pub, I told them of my chat with Brahms. They looked at me with protective bemusement, then ordered me another beer. Much as I hoped for further insights from the master, that was the last time he spoke to me. Perhaps my biggest problem with Schoenberg’s orchestration of the piece is that he doesn’t score that melody for horn. Maybe I should orchestrate the G minor, too- just so I can hear that theme as Brahms conceived it?

4- I do like Top ___ lists. Brahms expert extraordinaire Barney Sherman has a good one going on his website of the best Brahms recordings of the last decade. I completely agree with his choice of Jonathan Pasternack’s bold and thought-provoking First Symphony on Naxos, and I was also pleasantly surprised by Rattle’s BPO cycle in general. I have in my head a post on the best Brahms cycles of all times, and the best Brahms conductors of all time, but in the meantime, check out Barney’s list

5- One thing Brahms was definitely wrong about is the original version of Schumann 4. It was on the radio this week in a rather terrible performance, but even trying to listen with open ears and not worry about the ugly sound and slipshod ensemble, it left me completely unconvinced. It’s not better than the final version- it’s not nearly as good in any way. Composers know when a piece of music is at peace with its material. When it isn’t, they revise (then, or when copyright has expired). That’s what Schumann did with his Fourth. Brahms, Joachim and Clara Schumann were all ambivalent about Schumann’s late work because it reminded them of his final illness. That is completely understandable on a human level, but Brahms’ preference for the manifestly not-quite-finished original version of Schumann 4 is not a mistake anyone else needs to make. As with Sibelius 5, it’s great that there are recordings available of the original so we can learn how a master composer takes a piece from flawed to flawless, but the idea that both versions are equally valid, or worse yet, this idea that the original is somehow better, is complete and total horse-dung. And yes, the orchestration of the revision is better.

6- I’m conducting Brahms 2 tomorrow night in Guildford. Brahms is probably most often compared to Beethoven, and yet I find conducting them almost mirror-image experiences. With Beethoven, I find that my take on the symphonies changes very little from performance to performance or orchestra to orchestra. The challenge is always to try to get that little bit more alive, more together, more articulate, more in tune. In other words, I go into the first rehearsal knowing exactly what I’m aiming for and at the end of the concert, I tend to rate my success or failure on how close I got to that ideal performance. With Brahms, I find that doesn’t happen. Whatever I may be thinking about the piece at home in my study, when I’m with the orchestra, I feel an overpowering imperative to follow my gut. Everything is on the table: tempo, phrasing, rubato, articulation, not only from orchestra to orchestra, but from rehearsal to rehearsal. I think the best Brahms conductors tend to be sophisticated improvisers- Jochum, Furtwangler, Kleiber. Brahms’ letters all point to tasteful flexibility of tempo, and a spontaneous approach to performance as being essential for bringing the music to life. What is interesting is that Brahms’ music is even more organized, even more rigorous than Beethoven. In Beethoven’s music, his obsession with organization tends to demand that the performer be similarly structured. Often in Beethoven, you have to fight to make a tempo work when it may sound bad at first. Not so in Brahms, where the only right tempo is the one that is right…. right now. In Brahms, the music is even more structured, but the performer has to be in the moment. If you conduct the same Brahms 2 on consecutive nights, at least one of those performances is going to sound contrived or dull.

It’s hard to explain just how compelling that inner voice is that says “this needs to be more relaxed tonight” or “move it along” is when I’m conducting. It has at least the authority of Brahms himself on that Central Park bench so many years ago. When Brahms tells you to go to plan B, plan A is just no longer an answer. I’ve also learned that sticking with plan A as I imagined it at home is a recipe for disaster. If you don’t listen to what the music is trying to tell you in Brahms, the music suddenly becomes stilted and wooden. I suppose this experience has made me incredibly suspicious of the recent fashion for trying to replicate performance traditions in the Brahms symphonies based on descriptions of performances that took place over a century ago. Bulow and Steinbach knew better than to try to play a Brahms symphony with the same rubato two nights in a row. They would have found any attempt to recreate a 100 year old tempo nuance as described in words extremely funny.

7- I’m just finishing reading Malcolm MacDonald’s vast Brahms study. What a great book! All of his analysis is interesting and spot on, the biographical detail is vast, interesting and sensitively presented and the book is actually fluid and readable. Every Brahms fan should read it.

Ken, I presume you are referring to the BBCSSO/Runnicles performance of the Schumann 4 original version last night? I quite enjoyed the brisk account which seemed to point up the difference nicely, but never mind! Is is me, or are there several different versions of the ‘original’ floating about. Each one I hear seems to be that bit different. It’s the same with the super ‘Zwickau’ fragment, I think, or am I imagining this, too? Thought I would check with the Schumann man!

PS – the Brahms 1 last night on the radio from same concert was going so well until the usual stumbling point at the coda. That chorale broadened beyond all imagining and taste!

This is why Brahms ‘swings’. Also why it’s such a challenge. I wonder how he would be interpreted by a jazz ensemble. That is something I’ve always wanted to hear!

@Nicole

Search Brahms Jazz on Spotify – there are some jazz versions of his 5th Hungarian Dance and his famous Lullaby

Great post, Ken. Love the idea of sophisticated improvising in a Brahms performance! I’ve just been reading the Walter Frisch book on the symphonies (http://www.amazon.com/Brahms-Symphonies-Professor-Walter-Frisch/dp/0300099657/ref=sr_1_2?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1332513353&sr=1-2) – some interesting stuff in there.

Thank you, Ben!

Hahahaha, I’m such a space cadet! I actually saw him perform this live 6 years ago and forgot. Whoops!

Hi Ken, what can I say but a big thank you for the generous words about my Brahms book. Now, if only that could sell a few more copies – it’s hardly moved in the past few years! What you say about tempo – I think it connects up in some way to his love of Hungarian gypsy music (which he was smitten with very early on) and the improvisatory, of-the-minute nature of tempo & rubato there.

First, Ken, thanks for the shout-out on my blog post! Second, i totally agree about the Schoenberg orchestration (yuck) and can barely wait to hear yours of no. 2 (how DO you orchestrate the opening? I have an idea of a sound popping into my mind). AND the bit about the horn sound in op 25 first movement. And the sophisticated improvisers. AND Malcolm MacDonald – truly awesome (bravo, sir!) and I, for one, and going to Amazon to buy it, having merely borrowed in the past.

@Peter M

You’re absolutely right- there are some dodgy “original” versions of the Schumann out there. I’ve pasted an excerpt from the new preface to the new Breitkopf Urtext version. It seems that Brahms actually wanted more of a hybrid version, which is what Wullner made (although not incorporating all of Brahms’ ideas). Most performances before the new edition came out would have been reprints of Wullner, which included quite a few details from 1853 according to Jon Finson.

“Brahms then turned to Franz Wüllner, conductor of the Gürzenich Concerts in Cologne, who performed the first version in October of 1889 with great success. It was Wüllner who broached the subject of publication with Breitkopf and then with Brahms, most likely right after the performance. Brahms replied, “As concerns the Schumann symphony, everything is fine with me, and it is very lovely that you have performed it. […] You seem to share my view of the value of this version.That would have to be entirely the case, if you want to effect publication by Härtels. One prints no symphony out of piety.â€25 In December 1889 Wüllner secured Breitkopf & Härtel’s support, and this occasioned a more explicit comparison of the two versions by Brahms: “But just now your letter alarmed me, because it appeared to me as if you wanted to have the old version printed simply as a curiosity for the bookcase? I find it just delightful, that the lovely work was right there in the loveliest, most fitting vestments. That Schumann draped it so heavily later may have been prompted by the bad Düsseldorf orchestra, but all its beautiful, free and graceful movement has become impossible in this ponderous costume.†26

Brahms desired a practical edition for performance, and he went on to wonder whether Wüllner might not adopt the transition from the second version for the bridge between the introduction and allegro in the first version and the later mensuration for the body of the first movement. The notion that the first and second versions might be conflated to produce a performing edition opened Pandora’s box. Wüllner rejected changes in structure or mensuration. “From the eighths in the first version’s Allegro di molto] one gets more of a motivic impression, from the sixteenths [in the second version’s Lebhaft] more an impression of passagework, and Schumann certainly intended the former,†he wrote to Brahms. But at the same time he began to consider some editorial liberties, “On the other hand, I have already permitted myself minor alterations of instrumentation i.e., taken from the new version) in performance, though in quite discrete proportions. Perhaps one could have such minor changes printed in smaller notes, so that anybody would be free to adopt them or not.â€27 Brahms endorsed this approach in his reply, and in doing so moved away paradoxically from the original instrumentation that so appealed to him.28 In the event, Wüllner made more than just a few “minor alterations†to Schumann’s original score: he indulged extensive modification of articulation, phrasing, and dynamics, and even added some doublings and counterpoint from the 1853 print. Breitkopf did not print these changes in smaller typeface as originally intended, and thus it is impossible to see the extent of Wüllner’s interventionin his 1891 score of the first version.

If Schumann had left the first version in a chaotic state, Wüllner’s emendations might be understandable.But the composer’s autograph for the first version is clear, mostly consistent, and entirely adequate for performance. Though it contains two levels of correction made before the premiere in December 1841, the score gives ample testimony to the command of orchestration Schumann had developed over the course of the “symphony year.†Some may always feel that Schumann tightened the formal logic of the piece when he revised it later, but his orchestration is largely unproblematic. This alone would justify a new edition, quite apart from the intellectual curiosity such a score naturally attracts. Those who choose to perform the first version should bear firmly in mind the proportions of the ensemble for which it was fashioned, however. The Gewandhaus orchestra was relatively small in 1841 (about 50 players), with a string section about half the size of most modern symphony orchestras. An orchestra of this size and disposition will have few difficulties with balance in passages that Wüllner regarded as problematic.29

@Peter

I’m afraid I didn’t hear the personnel announced- I’d be surprised if Runnicles could conduct something so sloppy with such a fine orchestra. He’s a pretty great musician, but we all have our off days or our off repertoire. It sounds like it was part of a huge programme.