Klangfarbenmelodie, or “tone colour melody” is one of those 2 dollar words we all learned in undergraduate music history class. Simply described, in Klangfarbenmelodie, a single melodic line jumps from instrument to instrument, creating a more-or-less constantly varied coloration of the melodic line. It’s a word we normally associate with the composers of the New Vienna School, and fair enough, Schoenberg himself coined the word in his treatise Harmoniliere.

Wikipedia offers a simple example of the technique in which this line of Bach

Is orchestrated by Webern as seen below-

However, there’s nothing new under the sun, and the actual technique of Klangfarbenmelodie was in use long before Schoenberg coined the term. Robert Schumann’s Second Symphony offers one of the earliest, most extended and most interesting examples I know of (although, like everything good in music other than the fugue, the technique was probably invented by Haydn).

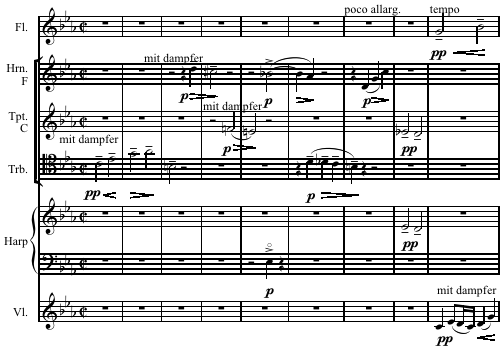

In the symphony’s opening bars (click here to listen), Schumann introduces two main thematic ideas- one, which I call the “fanfare” theme is actually a quote from Haydn’s last symphony, heard initially in the brass. It starts on the downbeat of the first bar and is characterized by its melodic rising and falling perfect fifth (C-G-C), and its clearly articulated rhythms, which continually emphasize the strong beats of the bar.

I call the other idea, heard in the violins, cello and bass, the “looping” theme. This theme is less rhythmically varied than the fanfare, consisting mostly of quarter notes (crotchets), but is also more metrically unstable, since it starts on the 2nd beat of the first beat of the bar. The combination of this empty downbeat with repeated ties and repeated pitches (often mixed, as in the 3rd bar, where the violins repeat pitches while the cellos and basses are tied) creates the impression of the melody “looping” over the barlines. Note, also that where the fanfare theme is all wide, perfect intervals, the looping theme is made up entirely of 2nd and 3rds, starting with halfsteps, and not opening up to a perfect fourth until the fourth bar of the piece, when the looping theme starts over. This is also interesting- the fanfare theme is a four-bar unit, the looping theme a three-bar unit.

The tension between these two ideas is going to be key to the enfolding of the entire symphony. One of the first attempts to resolve the tension between the two ideas occurs in the development of the first movement, and Schumann chooses to use the technique of Klangfarbenmelodie to bring this bit of musical drama to life.

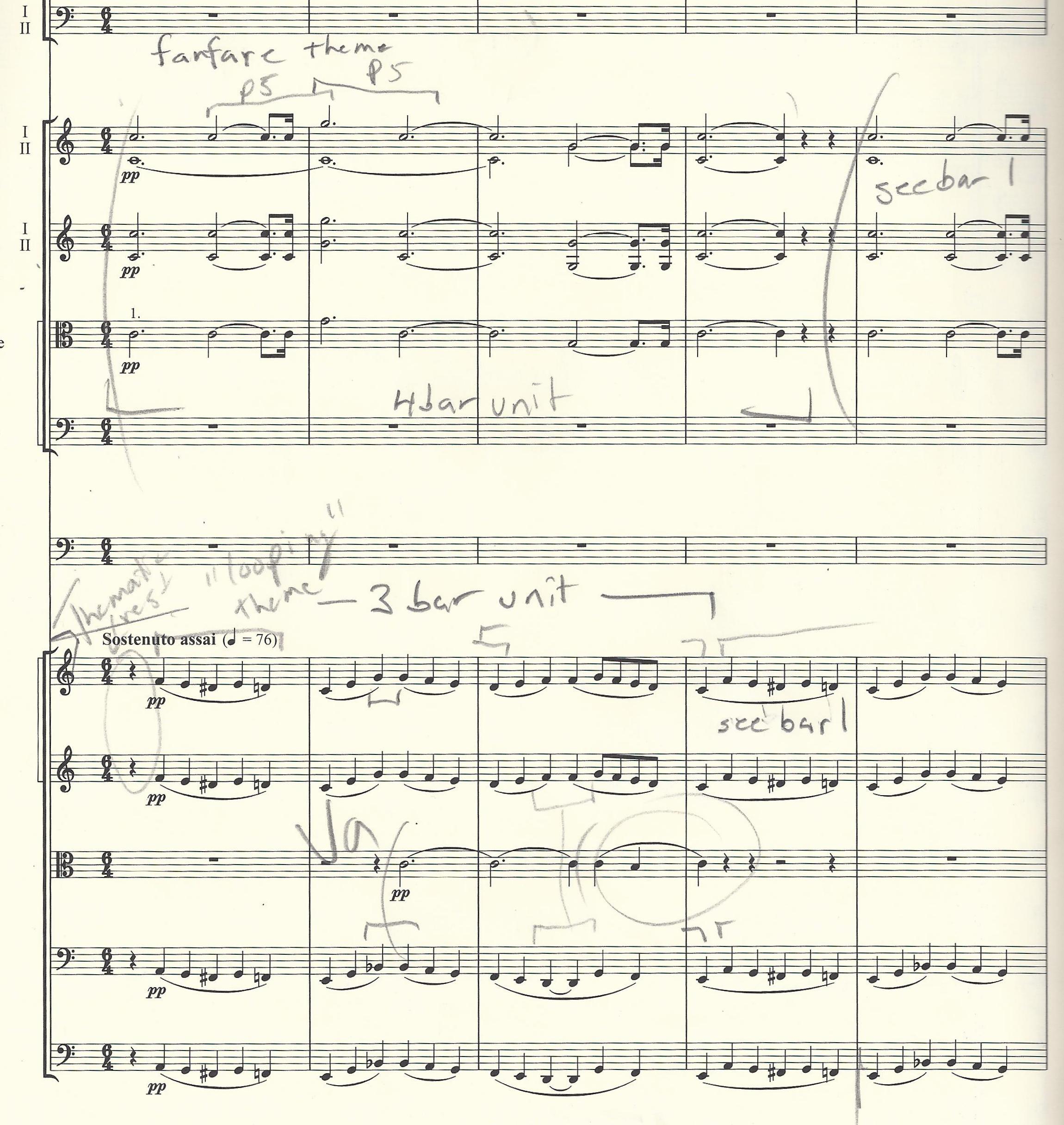

From the second beat of letter D, if you follow the top line of the woodwinds, you can see that Schumann is attempting to resolve the tensions between the looping theme and the fanfare theme by integrating the rhythmic information from one theme (the “looping” crotchets starting on the second beat of the bar”) with the pitch information from the other (the rising and falling perfect fifth from C to G to C, the same pitches as the opening brass fanfare).

You can also immediately see that Schumann has taken the long opening line from the beginning of the symphony (the first violins carry the main voice of the looping theme for the first 13 ½ bars of the piece), and divided it up into a Klangfarbenmelodie. Every bar, on the second beat of the bar, the tone colour changes, as the main melody and its harmonization are given to a different grouping of four woodwind instruments.

Also, starting from the 2nd bar of D, Schumann doubles the main melodic voice in the violins, but only for the 2nd and third notes of each 3 note grouping, and he switches each bar between first and second violins. In a way, this is an extension of the thematic rest which begins the symphony- instead of waiting one beat to start the melody, here the violins wait two.

Already from the fourth bar of D, however, you can see that the tensions between the two ideas is too great to be easily reconciled, and the open fifths collapse into stepwise motion.

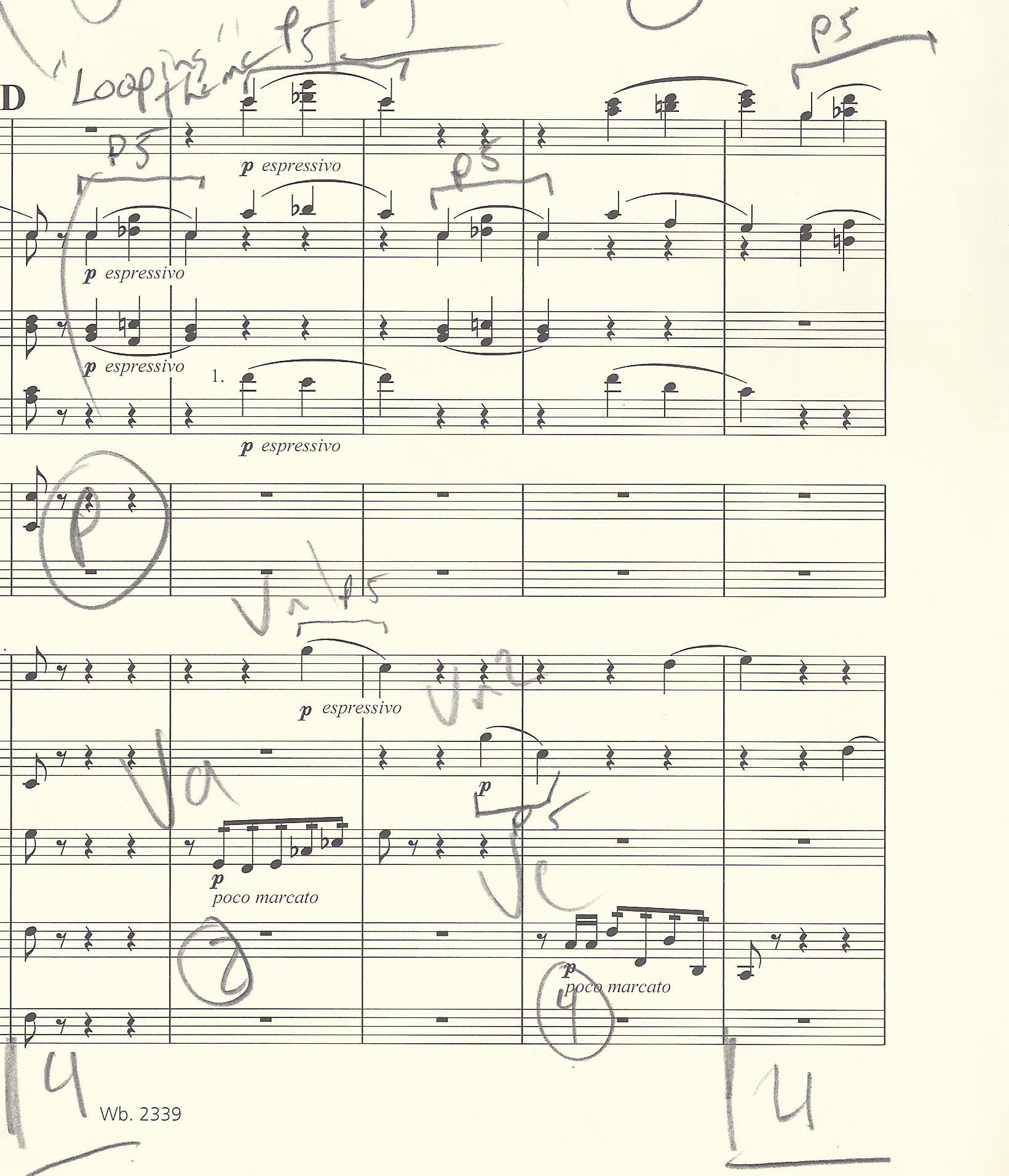

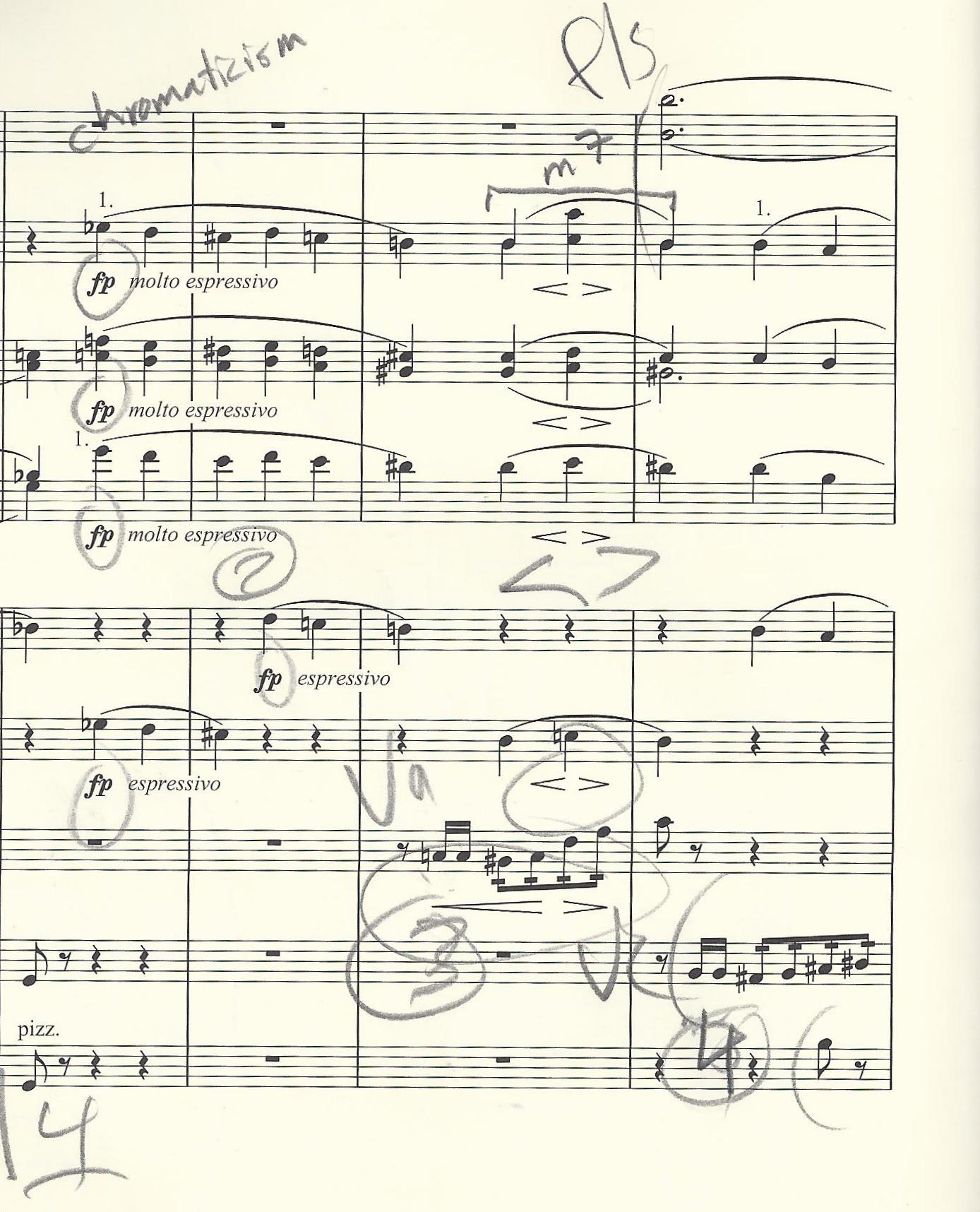

By the 9th bar of the passage (above), the chromaticism of the opening bar of the symphony’s looping theme is overwhelming the open fifths of the fanfare. Instead of perfect fifths and fourths, the only wide melodic intervals in the next eight bars are minor sevenths, full of instability and tension. The role of the violins becomes more active, with every note of the theme now covered by alternating violin sections. Eight bars later, the drama becomes still more intense (although the prevailing dynamic remains piano) when Schumann, more or less flips the orchestra upside down, with the main melodic line now in the violas, cellos, basses and bassoons, and the violins taking over the agitato 16th notes that the violas and cellos have shared thus far. Now, the cellos have the entire melody, as the first violins do at the beginning of the symphony, but Schumann still makes sure that the orchestration never repeats in any bar. Note, for instance, how in bar 142-3, he only has the basses playing their arco “D” in the second bar, when the sequence repeats in 146-7, the basses sustain their “C” for both bars.

In fact, every time the sequential nature of the music creates a possible trap, where Schumann might repeat himself, he makes sure that the orchestration is always varied. Looking back to letter D, you can see that the wind choir in the 1st and 3rd bar is the same (oboes and clarinets), but only in the 3rd bar does he double the last two notes of the unit with the 2nd violins. In the 2nd and 4th bars of D, again, the wind choir is the same (flutes, first oboe and first bassoon), and here, the doubling with the first violins is also the same. However, in the 2nd bar, the violas have the agitato theme, in the 4th bar, it’s the cellos.

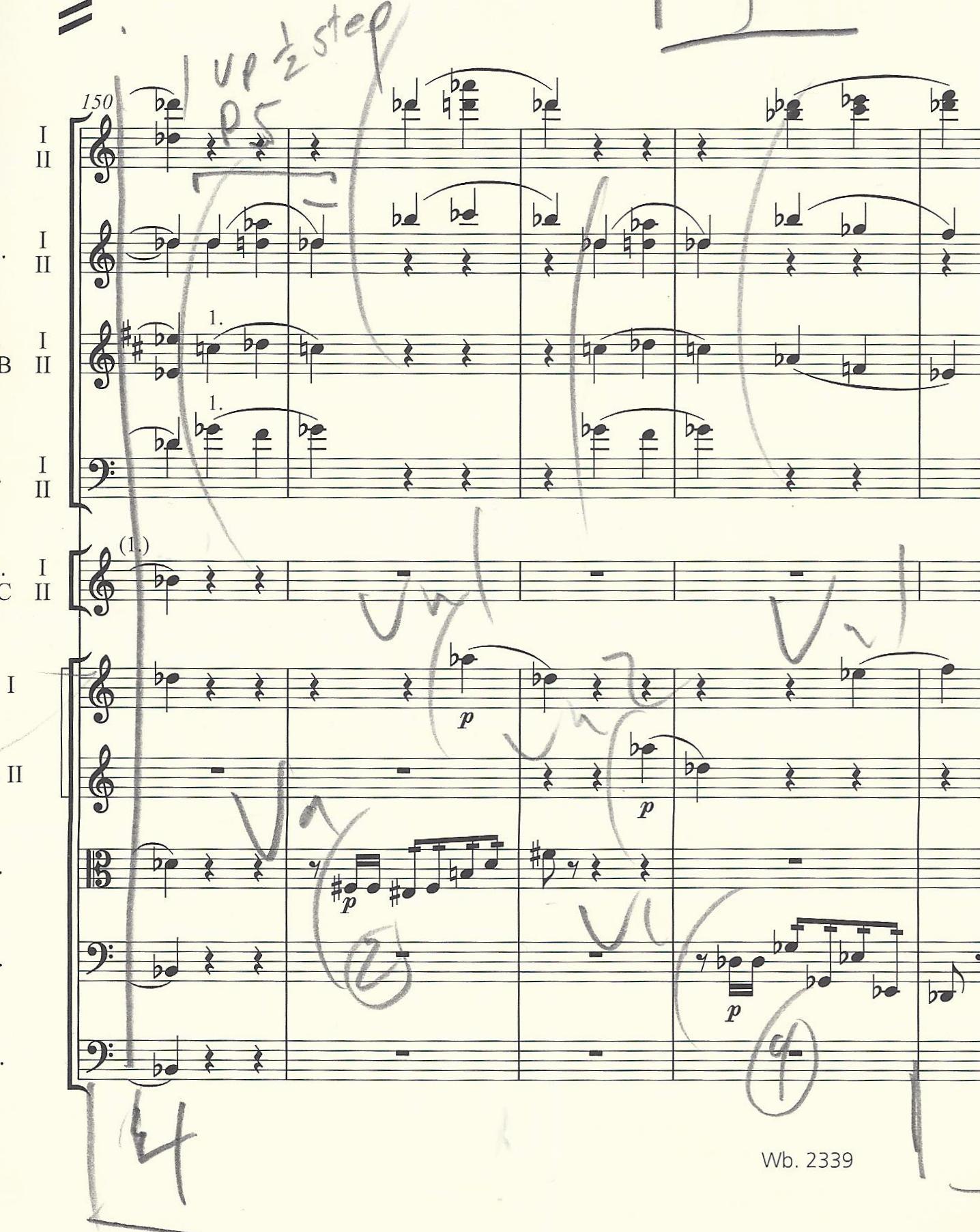

Letter D begins a 24 bar developmental unit, in which no two bars have the same orchestration. In bar 150, Schumann starts a repeat of this developmental unit, with all the pitch material moved up a half step, so instead of C-G-C, the melody begins Db-Ab-Db.

Even with this repetition of material, the orchestration is still varied- right away, Schumann starts with the first bassoon taking over the role of the 2nd clarinet at letter D, and from here onwards, in every bar the orchestration is different in detail from its parallel in the first passage.

All of this, I think, helps to underline the gradually mounting tension. This first attempt to reconcile the looping theme and the fanfare is doomed to failure, and this second time through the material takes a turn into violence in the last 4 bars of the 24-bar unit, and then Schumann unleashes one of the mightiest storms in all his music.

Schumann’s use of instrumental doubling is one of the most misunderstood aspects of his craft as an orchestrator. This passage is a perfect example of how artfully and skilfully Schumann uses doublings for expressive and constructive effect. It’s also a cautionary tale about the risks of tampering with his orchestration. Omit one doubling in this passage, as some conductors do, and you’re not just messing with the orchestration, you are tampering with the musical structure. If you don’t seat the violins antiphonally, as Schumann would have, I think you lose much of the interplay between first and second violins- the back and forth becomes between the two sections is much harder to perceive and much less dramatic. Finally, with a huge string section, in order to get any semblance of balance, you either end up forcing the strings to play painfully softly, losing presence and energy, or force the winds to overblow, losing the element of suspense. All too often, you can only just hear the top line of the winds and a huge, flabby string sound, and, instead of creating drama and a never-ending variety of color, Schumann’s well-thought-out, and beautifully crafted orchestration sounds muddy. When this happens, the fault is with the performers, not with the composer

Balance is only one facet of the difficulty of this passage. One has to balance letting the tension build up by letting the music feel trapped in these big loops with giving it direction and shape. One has to bring out all the details of accents, swells, fps and sforzandi while making sure the carefully concealed long line is there- remember, the individual players aren’t looking at the score, so they have no way of knowing where they are in the phrase, whether they’re in a strong or weak bar. I don’t know that I’ve heard a perfect rendition, although Cleveland, possibly alone among large symphony orchestras, seem to manage it pretty well with both Dohnanyi and Szell.

Just so you can see if we walk like talk, here is our performance with Orchestra of the Swan from our recent Avie CD. I decided to take a rather high risk approach and really not push this episode. Heard on it’s own, I find myself willing it to “take off” and go a bit. I’ve let the sample run on from here, so you can hear what happens in the next passage, when after all that moderately paced, piano, but hopefully agitato, music we really unleash the demons (thanks, Edward). Hopefully you can sense there’s a payoff to be had for not letting the previous section run along too comfortably. Click here to listen. You can follow along with my score in pdf here. Put on those nice headphones, please- with Bobby Schumann, computer speakers just won’t do.

Fascinating post Ken, thank you.

I assume you’ve read the chapter in Gunther Schuller’s The Compleat Conductor on Schumann 2? It focuses on the final movement and the four-bar phrasing which underpins the longer lines (and which, if properly observed, makes the music far more interesting and varied than most commentators accept or – say it softly – than most conductors seem to realise). It looks briefly at some of the points you raise here, but not in nearly so much detail.

Many thanks.

Hi Tom

I do know Gunther’s essay. I was surprised when I re-read it around the time we recorded it how much I didn’t quite agree with (mostly the specifics of those phrase groupings), but that’s what happen as you live with a piece for years, you find your own understanding of it.

Thanks Ken.

I thought when going through Schumann 2 that Schuller is guilty of shoehorning his idea into what the score doesn’t actually show in a few places. I still agree with his basic thesis, though – especially the way the theme starting after the two GP bars is treated as that usually gives an idea as to whether the issue has been spotted. Like all good rhetoricians, though, I think Schuller ends up trying to make the music fit his idea too much (rather than accepting that actually Schumann is too subtle to stick to that principle too rigidly – just as you wouldn’t expect to find Tennyson using unvaried blank verse).

I thought the best bit of his essay was the earlier part, when he looks at the same issues you do here. I am so glad to see you making the case so clearly for Schumann’s orchestration being not simply better than the ‘muddy’/’amateurish’ it’s so often wrongly labelled as, but a key part of his compositional method. He’s far more sophisticated in this respect than he ever seems to be given credit for. I liked your use of Webern to illustrate your point; I would love to know what Schoenberg thought of Schumann, as I think in many respects he’s barely less ‘progressive’ than Brahms.

Thanks again for the reply – and I should say I thought your recording of this work was terrific too. Always been a big fan of more modest orchestral forces in these works as it really helps with balance and the degree of varied colour that can be brought out.