Reflections on Debussy: East and West in meaningful dialogue

Peter Davison ponders the recent Reflections on Debussy series at Manchester’s Bridgewater Hall, discovering what its creative dialogue between East and West might tell us about the state of contemporary culture.

The dialogue between East and West has long been considered a fruitful source of new ideas and cultural renewal. Jung thought it might be the solution to Western Man’s spiritual malaise. The introverted spirituality of the East could temper the aggressive rationalism and materialism of the West. In these difficult times, we need more than ever some oriental enlightenment. While Western values seem to have won the day in Asia for now, culturally the dialogue between East and West has probably never been stronger. Those who read this blog will know about Ken’s recent Spring Sounds adventure, and it seems to part of the Zeitgeist. Over the last six months at The Bridgewater Hall, we have been promoting Reflections on Debussy; a major celebration of Debussy to mark the 150th anniversary of his birth. It also marks the date of the first Japanese diplomatic mission to Europe, so 1862 was a very significant year in the opening of dialogue between East and West.

The Japanese pianist, Noriko Ogawa, who plays Debussy’s music with great sensitivity and insight, was appointed to curate the series. Because Debussy had been greatly influenced by Japanese and other oriental cultures, we wanted to draw out these connections between East and West in the concert programmes. Not least, Toru Takemitsu, the greatest composer to come out of Japan in the 20C, saw Debussy as his mentor. This reciprocation of Debussy’s oriental interests made him an obvious source for repertoire. Noriko is also a great exponent of his music and a champion of contemporary Japanese music in general, so again, she was the ideal person to lead this exploration. Our partners for exploring the Debussy orchestral repertoire and Takemitsu’s works for piano and orchestra were the wonderful BBC Philharmonic.

First of all, it is worth saying something about the process of planning the series. It is fair to say that events rather overtook us in March last year, just as the series was being finalised. There was a meeting with Noriko and the BBC Philharmonic management, where we discovered that by coincidence Noriko would be in Japan while the orchestra were also touring there. They discussed the idea of meeting up. What happened next is well documented. On March 11, an enormous earthquake shook the North East of Japan and the subsequent Tsunami devastated a great swathe of the eastern seaboard. Noriko was in Kawasaki, her hometown. The orchestra were in a coach travelling between venues. In the following days, the orchestra’s predicament became headline news, while Noriko became an eye-witness expert, appearing on Newsnight and various UK radio stations. She went on to raise over £20,000 for the earthquake appeal and to be an eloquent spokesperson for her country. Amidst the destruction that was visible from the news media, one story was not told. The ceiling of the concert hall in Kawasaki (Noriko’s hometown) fell in. It was not in the epicentre of the quake, but the vibrations had exposed weaknesses in the structure. Noriko told me that her friend, the Japanese composer Yoshihiro Kanno, had been writing a work for piano and organ which would have been premiered at the venue, but this was no longer possible. It seemed the least I could do to offer to help out, and so the work was rescheduled for Manchester, receiving its first performance on the 25 May 2012.

If you are thinking that coincidence is at work in all of this, then I am sure you are right, although on a scale which is rather daunting. Noriko has been and the BBC Phil had been propelled into the limelight for regrettable reasons. I recall visiting the Japanese Embassy with Noriko not long afterwards and finding the staff there consumed by the fall-out of the disaster, yet they were courteous and helpful regarding our Debussy project. There are moments in your life, when you recognise the interconnectedness of things; when you realise that a concert plan in Manchester is woven somehow into the tapestry of world events and natural phenomena in ways that are too mysterious to comprehend. All I can say is that it gave added meaning and urgency to the concert planning process which made it more meaningful, giving it focus and purpose. It also put making music into perspective in a way that was humbling.

Working with Noriko was always a delight. She is an enthusiast with a big heart. You can put her in front of diplomats, students, children or disabled children and she will play with same spontaneous pleasure for all of them. As the planning unfolded, if you asked me, who thought of this idea or that repertoire, I can hardly say, because the flow of thoughts and ideas was river-like. Noriko’s playing, her knowledge of her own culture, her presence would stimulate my creativity, while my ability to convert ideas into practical reality would stimulate hers. She is a generous person and realises that it takes a whole team of planners, performers, administrators and technicians to put a complex event on, so she is genuinely grateful to all of them. She plays like a dream of course, and one of the abiding characteristics of the series was how she rose to each occasion. I was consistently impressed by her technical mastery, her stamina in performance and her ability to project a powerful sound or play with the nimblest dexterity.

The series was long and dense, so it would take many blog posts to give an exhaustive account, but I can describe the recital phase of the programme in more detail. The idea was that, through each day of events, to move from the formal ritual of Japanese culture to the chaotic world of Le Chat Noir – The Black Cat Parisian nightclub, where Debussy would mingle with his Bohemian friends. The inside of this sandwich was a more or less traditional Western classical concert, mixing Debussy with other music – often Japan-related, including works by Takemitsu, Yoshimatsu and Kanno. Each day of events was given a title, drawing attention to the play of opposites – Sound and Image, Innocence and Experience, Terror and Beauty, Nature and Form. The earlier orchestral concerts had focused on elemental titles such as Water and Night.

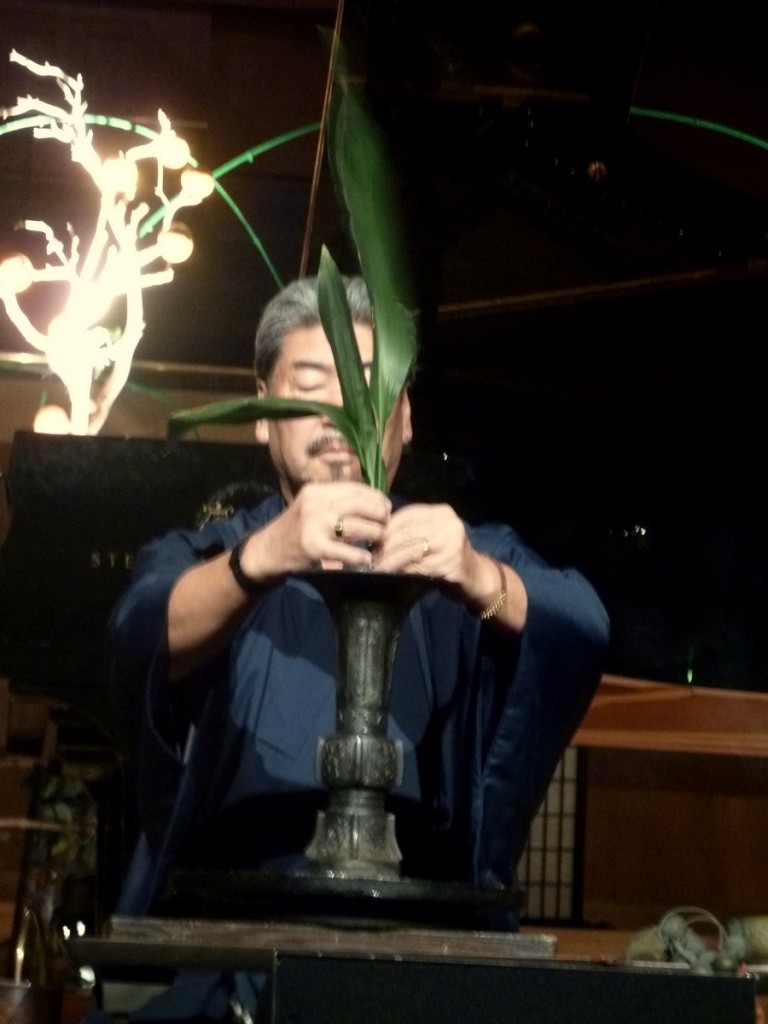

It is hard to identify highlights, but the concert of both Books of Debussy’s Preludes (Sound and Image) gives a flavour. We used the Halle orchestra’s Indonesian Gamelan – offering public workshops in the afternoon, because Debussy had incorporated the sound of the Gamelan into his music. Debussy expert (and one of the most articulate lecturers I have heard on any subject), Paul Roberts, gave an hour’s introduction to the music. We had asked the ikebana (Japanese flower-arranging) practitioner, Takashi Sawano to create a sculpture on stage, which he finished in front of the public complete with Buddhist ceremony. His visionary work exceeded all expectations and created a spectacular backdrop for Noriko’s performance. Her playing was immaculate and poetical; proof that playing the two books back to back makes for a rewarding concert experience. Afterwards, the audience were able to witness a Gamelan demonstration in the foyers, before hearing Estampes, which opens with Pagodes; an obvious echo of the gamelan sonority and harmony. The juxtaposition was revelatory.

Another remarkable event placed Debussy’s late sonatas alongside their Takemitsu equivalents. We placed the works to create a mirror image, gathered together an all-female, stellar group of performers and watched a miracle unfold, as the reciprocation between Takemitsu and Debussy was played out in fascinating dialogue. Emily Beynon’s sublimely eloquent rendition of Syrinx from off-stage sounded somehow Japanese. It called out to Noriko and Natalie Clein, already waiting in darkness on stage, who performed Takemitsu’s Orion without a break and with searing intensity. I have to mention Kyokjo Takezawa’s performance of the Debussy Sonata for violin with her exquisitely expressive energy. But perhaps most moving of all was Nobuko’s Imai’s performance of Takemitsu’s A bird came down the walk for viola and piano. He had written the piece for her and the concert concluded with this beautiful elegiac homage to her lost friend, who died in 1996 – the year the Bridgewater Hall had opened.

The centre-piece of the concert was the two trios for flute, viola and harp by Debussy and Takemitsu, for which Nobuko and Emily were joined by the Dutch harpist, Godelieve Schrama. These were performances which entered into the intimate heart of these two uniquely sensitive composers. The concert had been preceded by a lecture about the sounds of a Japanese Gardens by Prof. Masao Fukuhara, who made Takemitsu’s aesthetic world accessible– revealing the way our attention roves in a garden from one sound to another, how this erodes our self-consciousness and opens the door to the transcendental realm. Again, this concert was full of meaning; layers of connection, unfolding contrasts and contexts. East called out to West and vice versa. And what can one say about the players and their extraordinary skill and commitment? There was no hint of cynicism or fakery, just genuine feeling, great musicianship and heartfelt beauty.

Composers were given plenty of opportunity throughout the series. I commissioned five Aquarelles from five established British composers – water-based piano pieces which were played by Clare Hammond. I can only commend her enthusiasm for the project and the quality of the works. It would be invidious to make comparisons between such diverse compositions, for each was a unique interpretation of the brief, but what again struck me was their rich inventiveness, the enthusiasm for the subject matter and the integrity of those who were involved. Not least, the public responded warmly. The pieces have been published by Music Haven, so I am sure they will receive many more performances. I am grateful to James Francis Brown, Peter Fribbins, Alan Mills, David Matthews and Robin Walker for showing that new music can still connect with a mainstream audience.

We also found ways to engage with student composers and pianists through the Impressions of Manchester project, which was part of a wide-ranging and imaginative out-reach programme. Pianists and composers from the Royal Northern College of Music and Chetham’s school were each assigned a Prelude from Debussy’s Book One. The pianist had to learn to play the Prelude, while the composer had to respond with a Prelude of their own based on some experience of Manchester. The culmination would be a performance at The Bridgewater Hall of the twelve Debussy Preludes alongside their new counterparts. Noriko acted as mentor, giving masterclasses to each student pair on both the Debussy and the new work. She showed her great ability to put young players at their ease, and her great depth of experience in performing Debussy and new music was invaluable. The final concert was great reward for the hard work of the students, but even more interesting were the creative partnerships which developed between performers and composers. This was something unexpected, which again showed that dialogue to resolve differences produces extraordinary and positive results.

Lastly, I would like to say something about Yoshihiro Kanno, a Japanese composer little-known in the West. His music is dynamic and elemental, powerfully expressive of the Japanese soul which knows both the terror and beauty of Nature. His Sky Maze for organ and piano, which finally received its premiere over a year after the Japanese earth-quake, was warmly applauded. A representative of the concert hall in Kawasaki attended the concert and shed a quiet tear. She had led the organist, who would have given the premiere in Japan, to safety just minutes before the roof caved in. The dialogue of East and West was again very much alive in the music and the context of its performance – a true reciprocation. Yoshihiro is a good candidate to inherit the mantle of Takemitsu, and his music should be better known in the West.

I have only scratched the surface of the last six months, which has been education for all concerned. It has been an introduction to many aspects of traditional Japanese culture, as well as opening a revelatory window into the world of Debussy. Noriko’s last concert included a performance of his Douze Etudes – surely some of the greatest and most profoundly expressive music ever written. Difficult to play, esoteric and ironic at times, this is music that touches rare heights of pianistic and compositional virtuosity, all in the service of visionary expression. Why, I ask, is this music not played more often or held in greater public esteem? Why is Debussy not so highly rated as the three great German B’s? Why is he best known for his more sentimental miniatures? Perhaps for the same reason that the Western culture is in such a mess. The beautiful and the spiritual, the mysterious and the profound – these are minority interests, unless cloaked in reputational respectability or bland sentimentality. Meaning is hard won as an experience in musical life, where there are often just too many concerts in an overcrowded market-place. Meaningful music-making is so easily lost in the general noise. Reflections on Debussy reminded me just how hard you have to work to make music meaningful, yet there is a hunger for it and plenty of genuine talent out there, but not necessarily where you would expect to find it.

Links and photos:

Series Brochure download – attached

Fantastic post, Peter.

I especially like the idea of Debussy’s music as the embodiment the sort of East-West sanity you rightly point out we need. I can’t help but point out your last big BWH project was to do with Mahler. The two composers’ musical aesthetics are pretty different, but do you see in parallels in the way in which their music expresses a certain kind of sanity or enlightenment?

Debussy notoriously walked out of a performance of Mahler’s Second Symphony in Paris, although Mahler retained a following among prominent French liberals. For Debussy, the Austro-German symphonic school and Wagnerian expressive ambition were anathema. Mahler did conduct some of Debussy’s orchestral works and intended to programme Pelleas et Melisande at the Vienna Opera, before his untimely departure. The orientalism in Das Lied von der Erde, with its delicate and fleeting orchestral colours, its modal and pentatonic harmonies, has more than an echo of Debussian aesthetics. Perhaps Debussy’s neo-classicism towards the end of his life was bringing him in turn closer to Mahler.

Mahler was striving with heart and mind for truth, but truth was always retreating from his grasp, until those later works, when he found consolation in loss of ego and acceptance of fate. The striving turned to stillness. Debussy never had that kind of restlessness and scepticism, but instead observed Nature acutely – its beauty was for him almost like an objective truth which only the human ego taints with its subjective projections. Indeed, in Mahler too, Nature is sometimes a terrifying or beaiutiful objective presence, but more often than not is a mirror of the inner world with all its torment and contradiction. You might say that they both found in Nature a potential source of deep truth.

I think both men had great openness to the stimulus of outside cultures – whether from the East, from popular music, folk music, the classical music of other nations – Russia in particular. Truth was also something found from reflection on the full range of their experience. Both absorbed and were profoundly influenced by Wagner of course without ever imitating him slavishly, although keen to stamp their own personalities on the Wagnerian chromatic language. I wonder if Debussy’s “protest” against Mahler was partly to avoid being drawn into his visionary world, fearing it might prove more appealing than he would like to admit. Debussy was a great ironist in his public utterances and occasionally akso in his music. Composers rarely say what they really think about other composers in my experience.

I am not sure that answers your question – but if sanity and enlightenment come from resolving the tensions of opposites, then both composers went about that task assiduously, even if the results sound so different to the ear. You might say Mahler was seeking truth by heightening consciousness to a point of extreme clarity, until the last works, when transcendence comes from the loss of ego consciousness and acceptance. In Debussy, the erosion of boundaries and ambiguity; the dimming of consciousness and clarity remove the illusion of separation. But in his later neo-classical works, form and clarity, the definition and exploration of the musical idea become more prominent. Perhaps the late-works of both composers come close to an unlikely meeting of minds.