“The first rule of Mahler 9, is that you do not talk about Mahler 9″

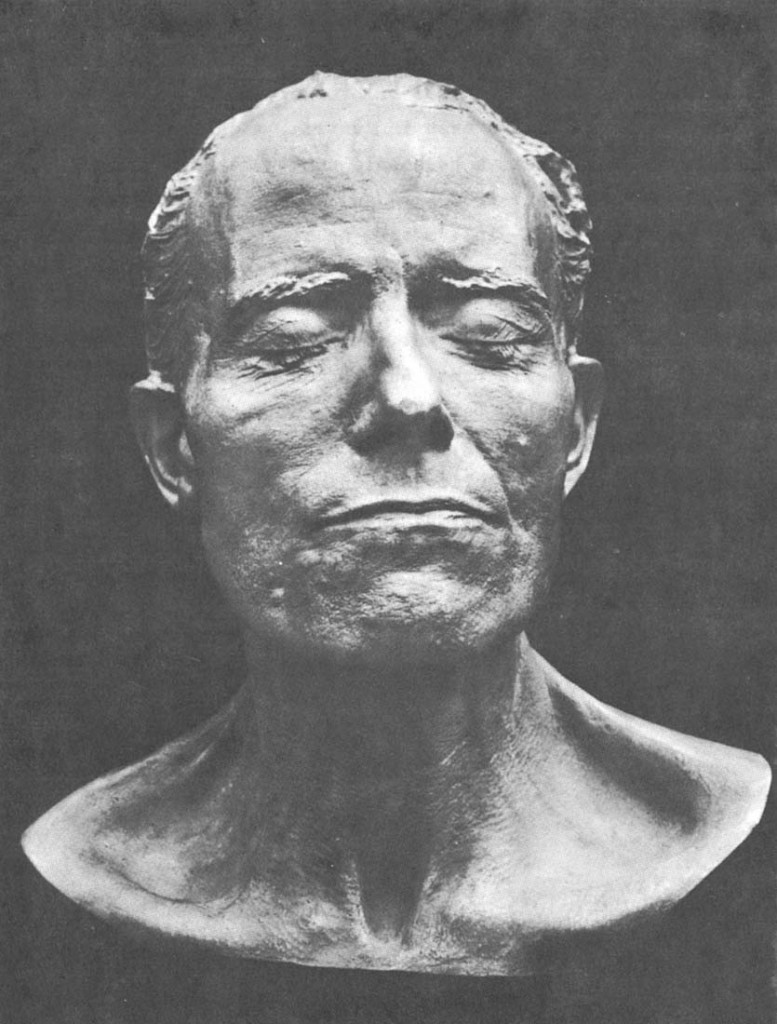

June 26, 2012 marked the 100th anniversary of the premiere of Gustav Mahler’s 9th Symphony. Bruno Walter conducted the Vienna Philharmonic- Mahler had been dead a little over a year. On the morning of this momentous anniversary last week, a long-time Vftp reader emailed to ask how I suggested readers should celebrate.

For those of us whose lives have been shaped by Mahler’s music, it’s hard to imagine a world before June 26, 1912. Since then, Mahler’s last completed symphony has worked it’s way up to being a leading contender for “greatest symphony ever written,” and Mahler has become recognized as, if not the greatest composer who ever lived, at least the most popular and influential composer in the classical canon.

But was Mahler’s music ever supposed to be popular? Were we ever supposed to agree on its value and importance? Mahler certainly knew it would be popular- “My time will come” he famously prophesied. And so it has. 2010-11 marked a biennial world-wide celebration of his legacy which led to countless performances, publications and pronouncements, and the invention of a new disease affecting both performers and critics, and perhaps even a few listeners: “Mahler Fatigue.” Mahler’s music is now produced on an industrial scale, with ruthless efficiency. Mahler has been franchised- we can replicate Mahler in any venue, with a minimum of specialist training now required.

I think it’s fair to say that we live in the age of McMahler.

I’m just barely old enough to remember a time when “Mahler Fatigue” sounded as fanciful as warp drive and human teleportation. Mahler’s music was controversial, and relatively rarely heard. A performance of his music was an event, and recordings were relatively rare. If you wanted something beyond the version of a given symphony your local record store had on offer, you had to order and wait for it (weeks or months), or hunt. The real treasures were often in used record stores. There was a “thrill of the hunt” in tracking down a long out of print LP one had been looking for from shop to shop for many months or years. I wasn’t much of a collector- I just wanted to find at least one recording of every Mahler symphony that was listenable. Even that was a challenge 25 years ago.

It was also exciting to meet a fellow traveler whose knowledge of Mahler extended beyond having played the last movement of the First Symphony at All-State orchestra. Even then, there were huge books to be read, box sets of LPs to digest and scores to collect- find someone who was also working their way through all that literature, who knew why the Solti/Chicago set that everyone had back then wasn’t enough, and you had probably found a friend. At the very least, you’d found a resource. The first Mahler scores I got my hands on from the library were ancient miniature scores with yellowed paper- the Sixth and the Ninth. I opened the Ninth first and sat with it silently at my desk in my room at my parent’s house for three hours before I admitted I didn’t know enough about harmony to read it. I then picked up the Sixth and made it through the first movement without the same kind of difficulty. Right away, I’d learned something important about Mahler’s evolution as a composer. Back then, there were no Dovers, and these scores from the local library were my only option- I kept renewing them for about three years, sometimes racking up huge overdue fines, and gradually adding to the stack.

Fortunately, it wasn’t all a lonely exploration, and meeting others who “got” Mahler was always exciting, largely because they tended to be interesting people and good musicians. Mahlerians I came across usually fell into one of two categories- on the one hand, you found people who were drawn to Mahler the composer of paradoxes and contradictions. They were fascinated by his mixture of head and heart, of grandeur and economy, of intimacy and extroversion. They saw in Mahler a musician-philosopher whose music was an honest and moving reflection of and answer to the myriad frustrations of life. They recognized in Mahler a man who was not just an astoundingly gifted composer, but a hugely important historical figure, a man who represented the culmination of 19th c. culture, but who was able to foresee the essential questions, crises and conflicts of the century ahead.

The rest were mostly brass players.

And, to be fair, some fell into both camps.

I’m glad that we all can download scores of all the Mahler symphonies from IMSLP for free anywhere, anytime. I’m glad I can find a live performance of Mahler symphony within driving distance of my within a four week window almost any time. I’m glad anyone who wants to, can buy any of several good box sets of Mahler’s music for less than an overcooked steak at Hamleys. But, all this cheap access comes at a price.

All of Mahler’s music is special and all of it is personal, but the final triptych of Das Lied von der Erde, the Ninth and the nearly-finished Tenth are works of art in which the window they seem to open into their creator’s soul means that those that know and love these three pieces tend to form very intense connections with the music. One’s relationship with late Mahler tends to be deeply personal and very private.

In fact, this relationship each of us has to the music we love is something very important and precious, be it Mahler or Magnard. It has become fashionable to denigrate the traditions of the concert hall as needlessly solemn, to compare the atmosphere, negatively, to that of church. I’m not a religious person, but it seems self evident that the only relationship in church that really matters is that between the worshiper and God. Having others there is helpful to the extent that it creates a heightened sense of energy, but their presence ought not to interfere in the one truly sacred relationship of the individual and the Deity.

So it should be in music, too- at any given concert, there will be people who have the most intimate and profound connection possible to the music, and those who are experiencing it for the first time. Some of those newcomers will remember that concert as a life-changing moment of discovery, others will miss the point completely. Reform the concert experience by all means, but honor that essential relationship between listener and music. We all benefit from the energy created when we all come together to share the experience of listening, but only if we respect each other’s relationship to the music. Each person in the concert hall needs their own space to create their own connection with the music.

I think one of the most painful aspects of any musician’s life is the way in which our personal relationship to specific pieces of music is constantly under assault. An orchestral musician who has loved and studied a piece for their whole life has all-too-often to contribute to a performance by an incompetent conductor who doesn’t know, love or understand it in any meaningful way. Perhaps even harder to take is the discovery that for all your love and knowledge of a work, someone knows it better, loves it more- one can suddenly be made to feel painfully insignificant and inadequate.

And when everyone decides to focus on one composer or one piece, it can start to resemble a flock of starving seagulls fighting viciously over some tiny morsel of food. Suddenly a piece of music as infinite in its scope as Mahler 9 becomes a small and shrinking thing, with a predatory mass ripping it to pieces to feed their own rapacious needs.

I also think the evolution in how we listen to music has damaged our connection with it. I don’t want to sound like one of those guys who tries to convince everyone that 78’s actually sounded better than SACD’s, but listening to an LP is fundamentally different to listening to any digital media. And yes, I use ALL the technology since the CD- iPod, streaming, clouds. Whatever it takes.

My LP’s have all been physically changed by the way I listened to them. Everyone’s were and are. My first copy of Mahler 9 doesn’t sound like anyone else’s. There is the scratch in the 3rd mvt from when my cat jumped on the turntable when I was 16. There is dust in the grooves from the bedroom I grew up in, the dorm room from my freshman year at IU, countless flats, my house in Oregon, and now the home in which my children were born. All of those little pops and crackles, much as I try to clean them away and minimize them, are really a history of where, how and when I listened to that disc. Every time a needle has been dropped on it, whether by me, a family member or a friend (some no longer with us), it’s made a tiny mark, it has personalized that piece of vinyl in some way. And think of all the different needles on all the different record players! An LP is a permanent record of your relationship with the recording because it is such an impermanent record of the music. Even as the listening history becomes richer, more personal and more complex, the record itself becomes of ever less and less practical use because the history of your life with the music gradually drowns out the music itself. I think there’s a wisdom in this- one only gets an limited number of encounters with an piece of music in life. Forget that, and you let life slip past you. You forget that every listen matters.

CDs promised a more permanent medium- with no physical contact between laser and disc, one’s listening history is no longer inscribed with every use. But CDs are still physical, and not so permanent after all. They do degrade and they do carry the scars of every time you drop them or leave them out. You can still hold one in your hand and remember buying it just after you had lunch with Sally the cute horn player in 1994.

How then, do we personalize our relationship with music in the age of Spotify? On the one hand, there’s no longer any need sentimentalize one’s listening history in a collage of pops, crackles and skips. It’s all kept forever in your profile. Not only can I see how many times I’ve listened to the first movement of Bruno Walter’s 1960’s Mahler 9 recording, I can also see the listening habits of most of my Facebook friends. I can see that SeattleJim listened to the Rondo-Burleske just before he jumped to a Justin Bieber track. Shame on you, SeattleJim. But, somehow, instead of being personal, it all feels a little voyeuristic and exploitive.

And call me sentimental, but it does bother me that we’re all listening to the same file. It’s a bit like sharing partners on an industrial scale. Even if the only thing that makes my old records unique is the extent to which I’ve fucked them up over the years, at least they are unique. I’d rather have a personal relationship with something singular, if flawed, than to share something factory-fresh with millions of others.

Most musicians I know work way too hard. Many find it hard to even listen to music outside of work. Music lovers are constantly being told that they’ve never heard the music played right, and what they really need is a Mahler 9 with no vibrato. Over the years of frustrating collaborations, compromises, social noise and routine performances, it’s all too easy to forget what it felt like to feel alone in the world with Mahler 9.

And that brings us to the whole point of this essay:

My advice for how to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the day Mahler 9 was first heard by human ears:

Don’t listen to it, yet.

Don’t talk about it for a while.

Don’t read any lists of must-have recordings.

Don’t take any advice from people like me.

When the time is right, give yourself some space and try to imagine what the world sounded like before Mahler 9 was first played. Try to imagine the world without this music. Try to remember your world before you knew this music. Create a vast and beautiful emptiness, a majestic silence.

Then, experience Mahler 9 in a way that means something to you. Listen to a recording you like, flip through the score silently or watch a performance on film. Heck, maybe you might like to go to a concert.

And then, here’s the important part:

Don’t tweet about it.

Post not to your Facebook wall.

Blog nothing on the subject.

Don’t make a freakin’ playlist.

Don’t tell your friends what you’ve done.

Don’t recommend that anyone else tries it for themselves.

Instead, reclaim a little bit of yourself for yourself and don’t let any other bastard seagulls try to rip it out of your beak. It may just be a small, rotting morsel of Mahler, full of sand and spit, but it’s yours now. You fought for it. Keep it.

Well the only response to that has to be “no comment” !

Can music be sacred when it has been consumerised? Is it possible to consumerise the sacred? Many religions have had a good go at this, and the Mahler cult surely gets close. But you are right Ken, once branded mass-marketing, big ego performers and general over-supply can infect even the most sacred cultural icon, which then begins to lose its numinosity. We prefer to discuss the lack of vibrato rather than the meaning of the music; we sit there comparing this performance with the last one we heard rather than drinking in the music as though we never heard it before. What I would give to rediscover Mahler again as I did almost 40 years ago, when it electrified my tawdry adolescent world with meaning and life! In truth, I have not listened to Mahler through long periods of that time, but when you come back to it after a break, you always find it is a measure of how you are changing. You “get” passages you didn’t “get” before. You see his point, why the Rondo Burleske has to be so spiteful and angry, before the elevated release of the adagio.

Can you rescue such music from the corporate wolves who are tearing it to pieces? Perhaps only as Ken suggests, by stripping away the detritus and waiting for that special performance to come along. It will be special because it speaks to soul, not ego.

Call me crazy, but I actually think we’ve slightly overrated Mahler 9 in the canon. I wrote about this the other day: http://evantucker.blogspot.com/2012/06/new-kind-of-friday-playlist-20-ten.html To me, it’s not a ‘universal’ piece that contains the entire world in it in the sense that The Marriage of Figaro, or Haydn’s Creation, or Mahler 3 do. There’s no doubt in my mind that it’s great, great music. But it’s a little too doom ladden, too fatalist, too quick to embrace death at life’s expense, to qualify as the greatest symphony ever written, and it’s not helped by lots of conductors who play it in a funereal style (no doubt with Walter’s later recording ringing in their ears as evidence without listening to his earlier Vienna performance).

And as boring as many latter-day Mahler 9 performances are, there have been some amazing ones in recent years. None greater, to my mind, than Claudio Abbado’s Berlin recording – even better than his later Lucerne performance. In the last twenty years, there’ve also been great recordings from Jukka-Pekka Saraste and Rudolf Barshai.

I find that I have more of the intensely personal relationship of which you speak with early Mahler. Beginning with the 5th symphony, Mahler’s music became far darker, more cynical, not nearly as life-embracing. It is sometime music, and still toweringly great, but it doesn’t tell life’s whole story. In earlier Mahler, we get the same kind of universal coverage of all life’s aspects which we can find in the greatest of the Viennese Classics.

Awesome and interesting post, Evan. I liked the bit about the Ten Commandments. I find that movie absolutely compelling- I can never turn it off, even though I find it very strange.

Of course, I completely disagree with you about the 9th, but I expect you’d already guessed that. It’s great that you’re willing to challenge any orthodoxy in an era of groupthink.