And suddenly it was April…

2013 is shaping up to be the slowest year yet for the blog, but not for lack of good intentions or good ideas. It’s just been, yet again, even busier and wackier than past years- a trend which is getting increasingly daunting as it continues

Looking back, it felt as if from January 2nd, when I returned from a short New Year’s break to a massive stack of scores and cello parts, to March 23rd, it has been one, long, mad dash of intense activity. After all of that, April has shaped up as a busy-but-not-crazy month, a time of transition and preparation for another frighteningly busy run into the summer holidays starting in May.

I wanted to quickly catch up with loyal readers and a quick look at what I’ve been up to, and what’s been on my mind. I think there’s too much to squeeze everything into one post, so I’ll break it up by months.

January

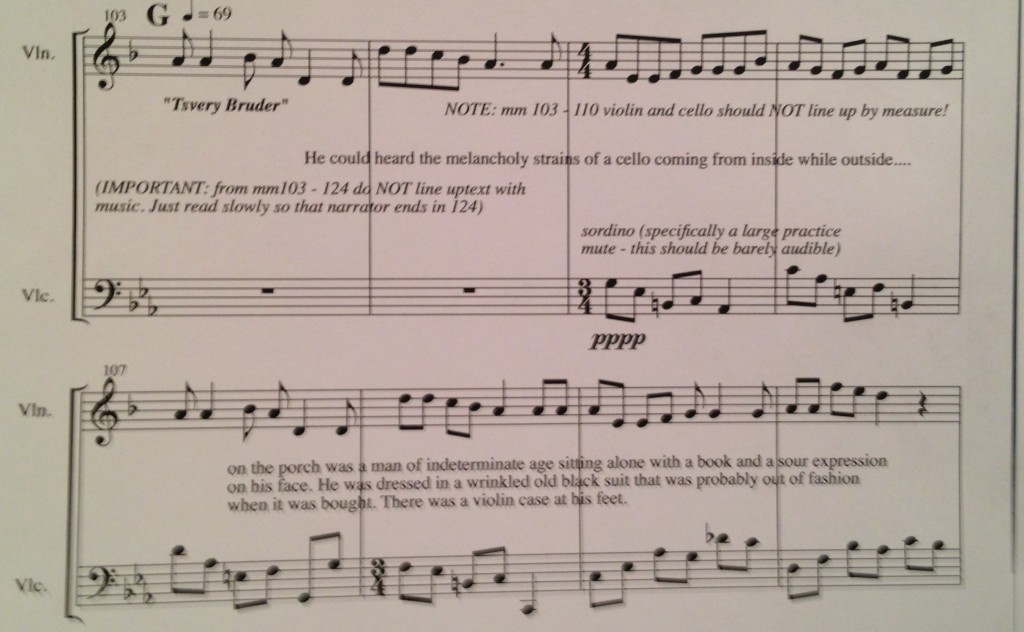

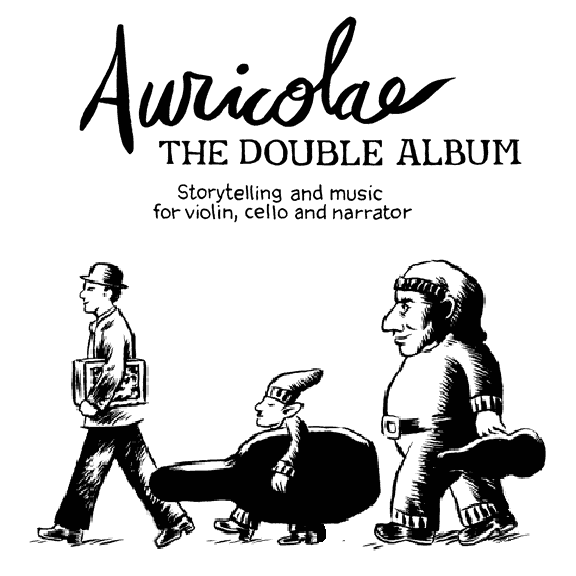

My first big undertaking of 2013 was a very, very exciting recording project. David Yang, the very multi-talented violist in my string trio (please buy our CD!!!!!), is also a very gifted narrator, and has a long-running “music and storytelling group” called Auricolae, for which he’s commissioned a staggering array of pieces by all sorts of fascinating and diverse composers. Auricolae put out a lovely if not well-promoted album in 2009 or so which I love and which my children love (buy it!), and I was thrilled when David asked me to play on the follow-up, the aptly-title “Auricolae- The Double Album.”

A double album of twelve virtuosic new works for violin and cello, no matter the intended audience, is no small undertaking. On the program were four pieces by David himself- a sort of Klezmer folklore-comedy tetralogy with its own Gotterdammerung-esque payoff. David’s music is solidly folk based (he self-deprecatingly insists he only uses 3 chord progressions. I think he’s being too modest- I count at least 5 over the four works), but incredibly witty and damnably challenging to play.

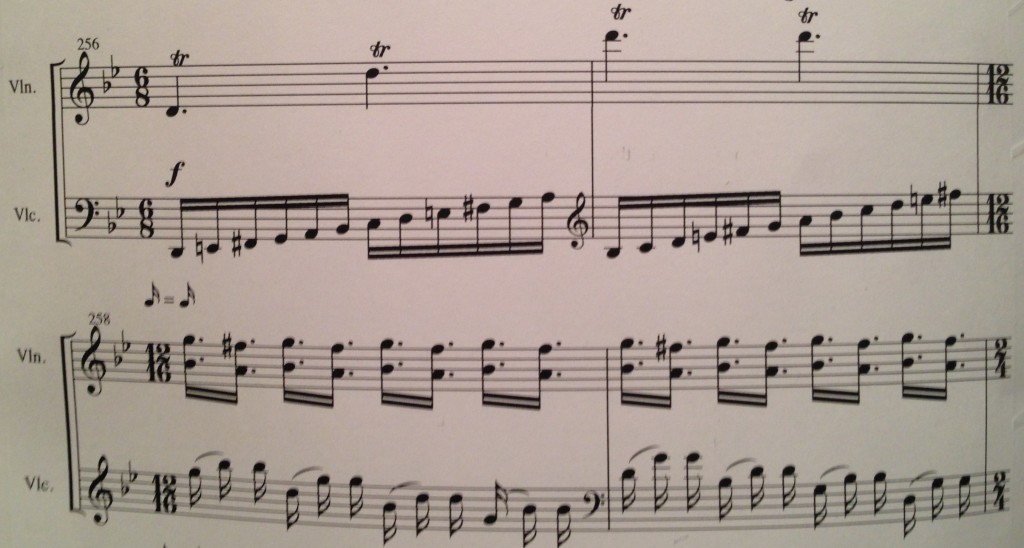

On the other extreme are three haunting miniatures by Gerald Levinson– music of extreme sophistication, rarified beauty and profound imagination. Levinson’s music is famously challenging, but, in the end, it was the 2 pages of harmonic glissandi at the end that nearly did us all in. It’s so frustrating to play that you almost would give up on the piece (that passage is about as idiomatic as transporting elephants on unicycles), but the impact for the listener is quite magical. Preparing a piece that requires at least 10 minutes of vigorous hand-washing to get the rosin off your fingers every time you rehearse or practice it is a big ask, but if it’s great music, you wash your hands and get on with it.

The violinist on the project was Diane Pascal, former first violinist of the Lark Quartet, now based in Vienna. We’d never worked together before, but hit it off straight away- we both like to work hard, have a laugh, and prefer to cut to the chase in rehearsal. Having played several of the pieces before with other fantastic violinists, it was interesting doing it with someone completely new- it’s always interesting to realize what bits of the experience are “the piece” and which are “the performance” and one’s understanding of where that line is drawn changes every time you do a piece with someone new. We rehearsed very intensely for four days in Cardiff, then recorded at our producer, Simon Fox’s private studio in Somerset for four days.

In the end, the Levinson proved not to be as hard to record as feared- it’s hard enough to play at all that you have to be so prepared to even start to rehearse it that it no longer ends up being all that hard to play once you know it. Does that make sense? Still, Diane and I were both hugely relieved to say goodbye to those harmonics. I loved learning and recording Jay Reise’s wonderful “The Warrior Violinist,” a heartbreakingly powerful story, with some staggering violin writing that Diane dispatched with truly jaw-dropping virtuosity. That was the first thing we rehearsed together, and when she finished the cadenza that starts the piece, I was, for once, speechless. The ending is one of the saddest things I’ve ever played- never mind that it’s ostensibly for children- I still tear up if I play it back in my head.

David’s pieces were always going to be challenging to record because the idiom is so familiar that everything has to be not only technically solid, but stylistically true, and there is, literally, always at least one nearly impossible run in every piece that takes gazillions of hours practice. As with the harmonics in the Levinson, each time Simon declared one of those licks “covered,” I felt ten years younger.

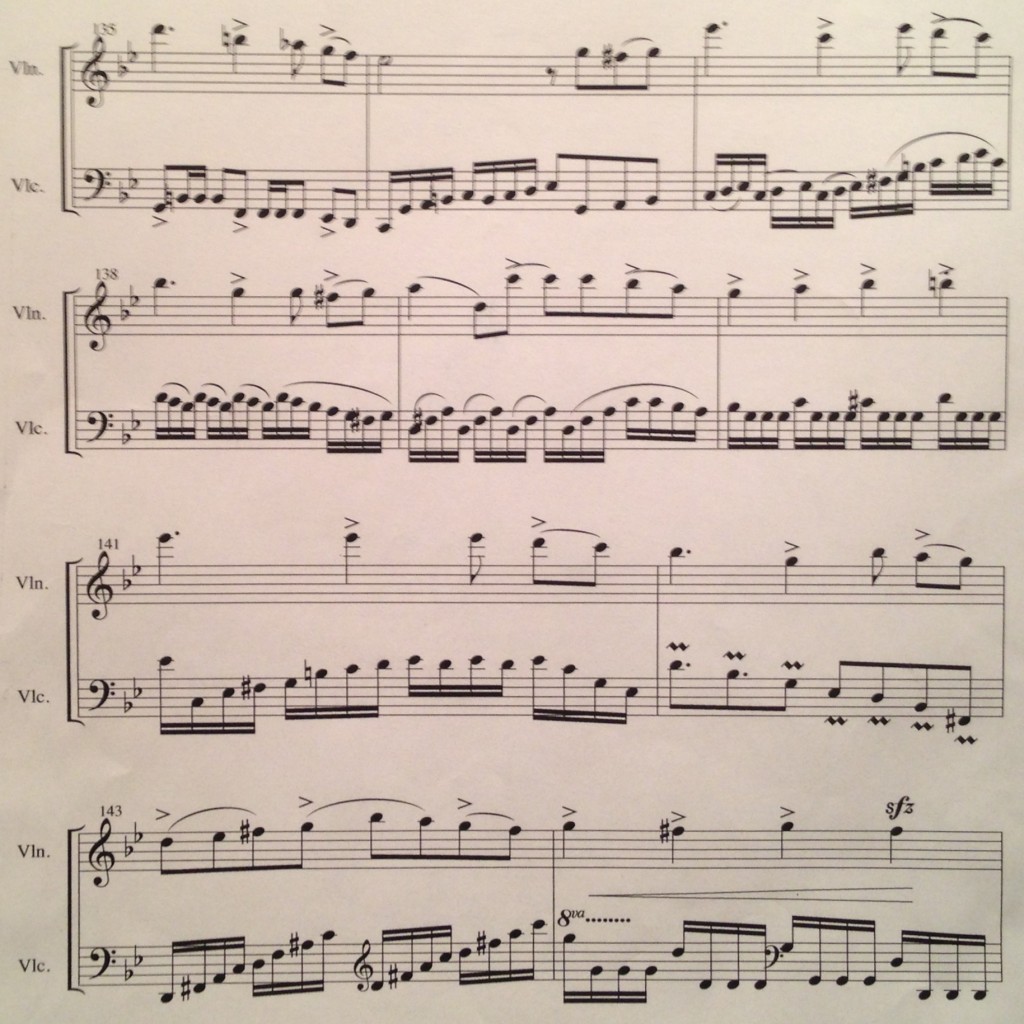

The Everest of Yang. Actually not too bad at a sane tempo, but once you ramp it up to quarter equals 500, it gets rather tricky

One of the pieces also includes a substantial quotation from one of the Bach Suites. In that case, I sent David and Diane off so I could focus, but it came together in basically one take. It did get me thinking about what it would be like to record solo Bach for real…

Stravinsky said it best- “good composers borrow, great composers steal” How great does that make this? The final episode of the new Chelm Tetralogy by David Yang

Harmonics also proved a nemesis in Andrew Waggoner’s excellent Stravinskian setting of the Emperor’s New Clothes. As with the Levinson, I had to grudgingly admit that they worked musically, but I do confess to believing that the novelty of writing extended passages in harmonics begins with Ravel and ends with the Shostakovich Piano Trio. There’s really nothing new left to do there, folks. Well, until Levinson and Waggoner, I guess. Let’s hope nobody else comes it with more new ways of using harmonics.

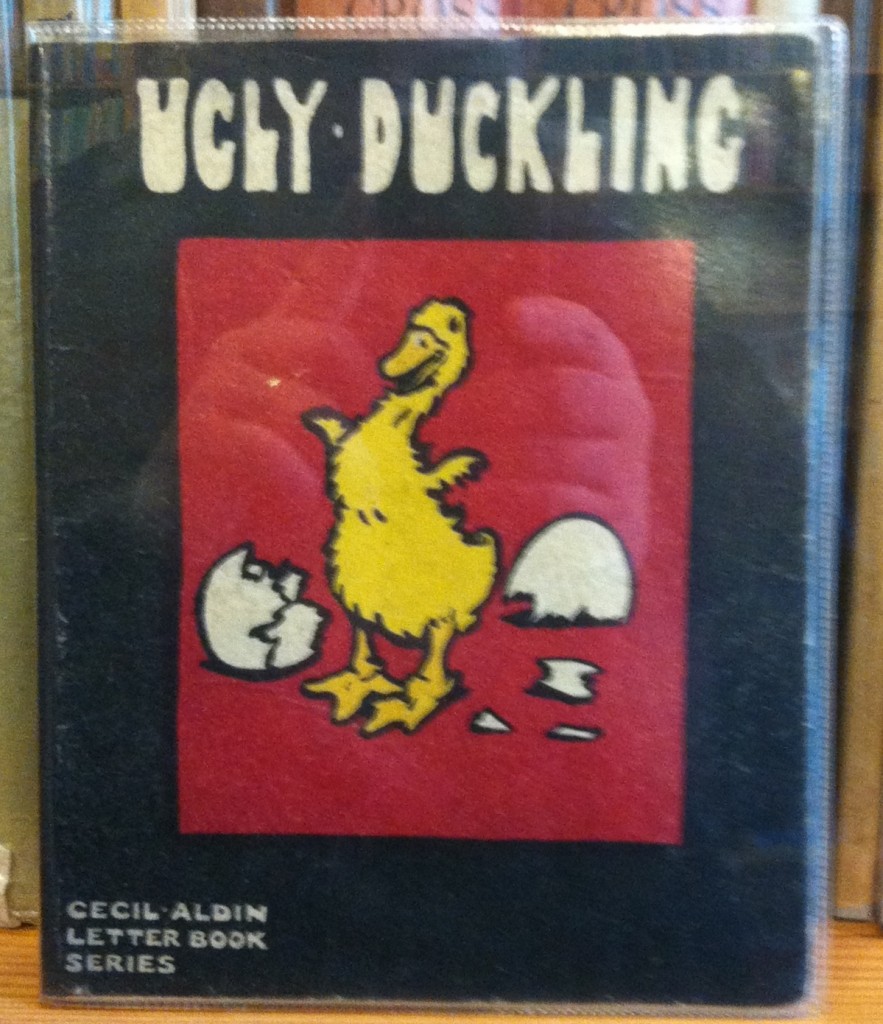

On the last day, we recorded my piece (see how I just dropped that in!)- a setting of The Ugly Duckling by Hans Christian Andersen. I hadn’t finished a decent-sized piece in at least fifteen years, but having played the Auricolae repertoire for a few years, I was fascinated to take up the challenge, and I also wanted to include a chance for David to display his real talent, which is playing the viola. I thought that the metamorphosis from duckling to swan in the story could be mirrored musically from a metamorphosis from violin to viola, with the viola emerging at the end of the piece as the voice of the swan. Between that original idea and the finished piece, a lot changed, and I’ll have more to say about the piece here when the CD is coming out.

What I do want to say about it all now is how useful the exercise of writing the piece was to me as a performer. Every book on conducting has at least one tip of the hat to the idea that “all conductors should study composition” or “every conductor should try his or her hand at composition,” and, of course, the study of orchestration and analysis, which all good composers pursue, is a core part of every composer’s training. That said, very, very few conductors I know ever compose anything, although many excel at arranging (especially once they realize how crap most pops arrangements really are). In fact, many of the great composers who take up conducting seem to end up paying a price for the time on the podium in reduced productivity as composers. Perhaps all conductors should compose, but most composers should avoid conducting? Many writers have speculated as to whether we’d have a great deal more from both Boulez and Bernstein if they’d not been so successful as conductors. What about Mahler- if he’d been able to give up the day job, would we have Mahler string quartets and maybe an opera to compliment the symphonies? It wasn’t always so- the great conductors of the past were the great composers of the past, and nobody ever accused Mendelssohn, Haydn or Bach of not being prolific enough. Wagner excelled at both according to his own writings. And if Bernstein and Boulez paid a price for conducting too much, was it because they were so extraordinarily good at it? Nobody ever worried that Stravinsky or Copland were conducting so many Brahms cycles that they didn’t have time to write because nobody was that interested to hear their Brahms.

Anyway, this little project gave me a chance to walk the walk- so they say every conductor should compose? Fine, I thought, bring it on- I can compose, I have composed, I shall compose.

I actually started improvising and composing very young, and maybe had a little bit of a spark for it. However, over the years I found that the composition student scene wasn’t for me, and that living the idea that every conductor should compose is harder than it sounds. First of all, even the really, really, really good composers often struggle to find people who really want to play and hear their music until it becomes established. In a busy life, it’s hard to rationalize spending time writing something that you know will attract even less interest than Otto Klemperer’s “97 Pedantic Variations on a Theme of Max Reger.”

I suppose one might think that a conductor is ideally placed to compose- theoretically, since I’m not financially dependent on composing, I can write anything I want, and could, if I wished, make one of my orchestras play it. I did try to write a piece for my orchestra in La Grande as part of my farewell season there, but I just couldn’t do it. I find total freedom to write whatever I like not-at-all empowering. It’s like being dropped down in the middle of the Pacific Ocean- all you can see is waves, but you know in exactly one direction, you could swim to shore in five minutes, but any other course would leave you lost forever in open waters. “Swim any way you like,” they say? No thanks! For me, the remit of an Auricolae piece- a story, an instrumentation, a known narrator and a duration- were incredibly freeing.

I think one often loses the playful freedom in creativity that I believe we’re all born with not because of an erosion of our capacity to create, but because our accumulation of knowledge leaves us too intimidated to allow ourselves the freedom to create to our own level. My recent experiments in writing always ended in frustration and humiliation, as I gave in to the voice that kept comparing my scribblings to “real” music- if, as a conductor, you set down your score of Mahler 6 and then try to write a five-minute piano piece, it’s all but impossible not to think you’re completely wasting your time and the paper you’re writing on. And the oxygen you are breathing. That voice can be useful if it pushes you to write better, but not if it stops you writing altogether- it always stopped me.

In that sense, the fact that I had a deadline and a recording planned was extremely liberating, and kept me on track through a number of brick walls. Creativity is a complicated process, but in the end, we’re social animals, and sometimes the rather shallow desire to avoid humiliation and disappointing one’s colleagues overrides concerns that seem stronger on the surface, like an a strong sense of being an imposter. I didn’t want to admit to everyone that I couldn’t finish Duckling, so I finished it.

So, to the axiom “all conductors should compose” I would amend: “should compse complete pieces.” It’s healthy and fun and interesting to play at composing, to improvise at the piano, to sketch and start things, but writing a complete piece, from beginning to end, is infinitely harder. After such a long break, I had several days where I just felt that I no longer had the energy or the skill to find a way through a problematic passage. Brahms said that ideas were a gift, but pieces are the result of hard, hard work, and it’s true. Composing anything decent is incredibly hard work- composers should get way more hugs and free beer than they do. If you don’t put yourself through that every once in a while, you forget what it’s like. You forget getting to that point where you want to light the piano on fire, and your brain feels pulverized, blank and dead, but you also forget how sometimes the solution just comes out of the blue the next day- as if all night in your sleep, the brain was quietly computing the equation of how to get from this idea to that one. Other solutions take longer- in some instances there were days and days of trying and failing before finally cracking it. And all of this struggle was just for a silly children’s piece. All conductors should compose. How dare we take charge of a symphony or an opera if we can’t even write a short work?

And of course, the end of the process, when I went back to what I do for a living, was rich with irony- here I was a professional cellist and conductor who had been playing at being a composer. At least I would know how to write for strings, I thought. And when I first read through it? I couldn’t play it! Shit. Too many fifths, some impossibly tricky runs, but at least I’d avoided writing whole pages of harmonics. It is irritating that one has to practice music one has written- you would think that having created it would get you some kind of pass, but no, apparently not.

In the end, Duckling was one of the two pieces we recorded on the last day of this amazing project- it had turned out to be the longest of the 12 works, and the inclusion of the viola meant it needed a different mic setup, so it made most sense to record either at the beginning or end of a day when it would cause minimum disruption to the continuity of the disc.

David had been amazing to watch throughout the week doing all the different accents and voices- I wish we’d filmed him. It was also incredibly interesting to see how Simon got him to use the mic as an instrument, making him speak up to the ceiling, straight on, to the left or down to the floor- all in the context of a live performance of often very complicated music. By the time he got out his viola and sat down to play, I’d almost forgotten that 95% of what I’ve done with him as a colleague is as a violist, and after days of the slender textures of only violin and cello (think Ravel and Kodaly Duos with a bit of jabbering on top), the sudden arrival of a string trio texture felt positively symphonic.

All in all, a big and hugely exciting project- and I haven’t even had time to mention several other remarkable works in that daunting stack of 12 scores. When was the last time you came across an album of contemporary music that could be enjoyed equally by hard core new music geeks, New Yorker-reading/latte-sipping culture snobs, and three-year-olds? I hope it sells 10 million copies.

The rest of January was focused on two other projects- first was the editing and mastering of the third volume of Bobby and Hans, a task that spilled over into February. I think the ins and outs of how a recording session becomes a record is something to talk about in a blog post all its own. Then, at the end of the month, came an SMP gig that culminated in Bruckner 2. During the intermission for that concert, I wrote a short poem about Bruckner and the trombone– I hadn’t finished a poem in many years, but this one has turned out to be the most popular post in the history of the blog (it took 8 minutes to write and got 1000 times more hits than this post will ever get). Who knew that poetry was so in? There’s even talk about reprinting it in The Bruckner Journal, pending discussion on the editorial board over whether they’re ready to publish the word “fuck” in a scholarly journal.

Perhaps the moral of the story is that conductors should compose, and write poetry.

Anything else? Fix cars? Juggle? Bungee jump? Smash atoms?

Out of sheer curiosity: why this feeling that “composition student scene wasn’t for you”?

any ideas on the release date for this album? i’d be _really_ interested in hearing it — your description of “the warrior violinist” has intrigued me…

regards,

sb

The CD is scheduled for release in the Spring of this year. Probably May, but possibly April or June. We expect to have a firm release date within a couple of weeks. I think you’ll really enjoy Warrior, as well as many of the other pieces on the disc. As it happens, we’ve just received the 2nd edit and I’m really amazed at how much great new music there is on the disc.

Thanks, Kenneth. I’m looking forward to the release and will be following your blog more closely. :)

Now in stores!

http://www.prestoclassical.co.uk/r/Avie/AV2292