When I was young and discovered a new piece of music that really blew me away, the urge to tell a friend about it was sometimes overpowering.

It wasn’t a feeling unique to classical music, and in my formative years, these moments came with thrilling regularity. Of course they did- I had so much to discover as I began my teens. I bought my first Jimi Hendrix record at 12, and was still unearthing bootlegs and live discs when I was 22. In my high school years, I heard all the Mahler and Shostakovich symphonies for the first time, discovered Miles Davis, Led Zeppelin and most of the cello repertoire.

(Composers James Marshal Hendrix and Philip Sawyers. This blog post is probably the first time these two musical giants have been linked. Read on to find why they should be.)

One quickly learned who to call for what kind of music. When a new (for me) Hendrix recording came my way, it was usually my friend Doug who came to mind. “Dude- you’ve got to come over this afternoon and check this out- I just got Axis- Bold as Love, and it’s even better than Are You Experienced.” He returned the favor later that week with Electric Ladyland. We were both cellists, but soon gravitated towards electric guitar (me) and bass (him) and within weeks, those listening sessions spilled over into jam sessions, and then my first rock band, as we found new friends to share our discoveries with. Before long, the new guys were calling me up with their own “dude, you’ve got to hear this “ moments. These encounters still seem to play out every day on Facebook and Twitter, but I have to say, I loved the ritual of getting together in person with a friend (or friends), putting an LP on the turntable, dropping the needle on that black vinyl, then handing your friend the album cover so they could check it out while listening for the first time (usually sitting on the floor-always carpeted in 1980’s Wisconsin).

People often speak of a level of cynicism or even bitterness among professional musicians. To be honest, I see very little evidence of this among the people I work with, whether as a conductor or cellist. I think this is all the more remarkable given the fact that we work in a highly-competitive field where we all have to detail with seemingly ever-increasing pressure and financial insecurity.

However, what hints of jadedness or disillusionment one might detect within an orchestra probably have at their roots a disappointment at the gradual disappearance of those “dude, you’ve got to come hear this” moments. They never go away completely, but they become rarer by the year. I think some version of that feeling at the joy of discovering music, and the recognition that you have a passion to participate in creating and recreating it, was key to most of my colleagues’ decision to spend their lives practicing, rehearsing, composing, teaching and travelling. If those moments stop, we have to question why we’re still in music.

Sadly, later life can never replicate the astounding bounty of our years of discovery. When someone tells me they’ve never heard Mahler 6 or A Love Supreme, I can only smile with envy. How lucky they are- to have that revelation awaiting them. I always tell them, “well dude, you’ve got to hear it.”

But although it’s been many years since I finished that first gluttonous inhalation of Bruckner, Mahler, Shostakovich and Hendrix, there are still endless wonders to discover in each of those works I’ve come to love. Coming back the Shostakovich Cello Concerto two weeks ago at the Scotia Festival with soloist Denise Djokic was a case in point- familiarity need not breed contempt. Of all the works I performed at Scotia (and well over half the works I played and conducted were completely new to me), it was the one I have the longest and most intense personal connection with as a listener, cellist, conductor and general lifelong Shostakovich nut, yet I found so many new and fascinating details in the score during my own study and the rehearsal process. Even in the concert, there were a couple of “dude, you’ve got to hear this” moments- things that I suddenly discovered on the page and tired to make happen with my eyes or mental powers as best I could.

My professional path has had its ups and downs, and I can say with a clear conscience that nothing good has come easy or fallen into my lap- I can’t but help think others have had some more obvious “good luck” in finding their place in the profession. However, I consider myself incredibly lucky that I keep seeming to have these “dude, you’ve got to hear this” moments. Discovering Hans Gál’s music is an obvious example- how had such a wonderful, communicative, complex and engaging voice been forgotten for so long? How did some nobody from Wisconsin get to make the first recording of his orchestral music? Crazy.

But Gál has not been an entirely unique case. A few years ago, I learned that my friend and colleague at Kent County Youth Orchestra, second violin coach, Philip Sawyers, was also a composer. He told me with the kind of tact you would usually use to warn your seatmate on a airplane that you often get violently airsick- “Ken, I’m terribly sorry to have to tell you this, but I’m afraid I’m a composer….”

Then I heard his music and looked at the scores, and it was another one of those moments. I even had a literal “Suzanne (I try to avoid calling her “dude”), you’ve got to come hear this” moment when I played the live recording of his First Symphony the first time. She came upstairs and our conversation went: “This piece is by Philip” “The one from KCYO?” “Yes!” “Get out of here! Really? Wow!”

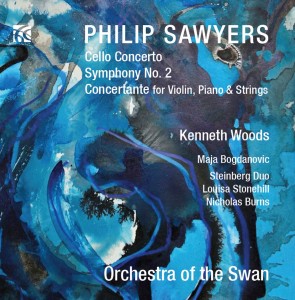

Since then, I’ve performed several of his pieces, and to my great, great, joy, Phil entrusted me with a recording of three of his works for Nimbus- his Second Symphony (review of the premiere by the London Mozart Players here), his incredible new Cello Concerto and his Concertante for Violin, Piano and Strings. After years of discussion and planning, we finally made the record on May 13th and 14th in Stratford with my friends in the Orchestra of the Swan.

Orchestras tend to be sober environments (well, perhaps not literally)- I imagine one does not say “dude, you’ve got to hear this” at a Berlin Philharmonic rehearsal (but I could be wrong). We tend to keep our passions and discoveries to ourselves because we’ve all made the mistake of sharing something with someone who totally turned their nose up at it. There’s nothing (I mean nothing) more soul destroying than coming offstage after a totally transcendent concert and saying to your stand parter “dude, wasn’t that amazing” and having them reply “Really? I thought it was torture from beginning to end.” You learn to keep your most important feelings about music to yourself. (And much more- I’ve never, ever written anything derogatory or even slightly critical about an orchestral colleague here, but I also often hesitate to praise too directly- one can’t help but fear that the time you write “Bubba played amazingly well tonight,” Bubba is down the pub telling everyone how badly you conducted) Nevertheless, I can’t think of a better band for “dude, you’ve got tot hear this” repertoire than Swan. Maybe it’s just because almost everything I’ve done with them is a bit wacko- Gál, chamber Mahler, Saxton and even a Shakuhachi concerto. I expect it’s more than that- I think it comes from the artistry and commitment of the individual members of the orchestra who somehow have found themselves- an orchestra of friends and chamber music colleagues. The name, the brand, the institution- none of these matter when bringing unknown music to life. It’s about having Dave, and Victoria and Nick and Mark and Chris and Sally and Anna and Liza and Shelly and Adrian all the rest of the gang there, listening and playing with expertise, skill, open ears and open minds.

It was a remarkable two days. Cellist Maja Bogdanovic, who played the Cello Concerto (it was written for her at the behest of the Sydenham Festival) is a significant talent and she played like an angel. I know my cello concertos- this is a very important addition to the repertoire. The Steinberg Duo brought tremendous commitment and a huge depth of experience with Phil’s music to bear on the Concertante- they’ve just recorded his two Violin Sonatas. And take after take, the orchestra showed incredible endurance and focus. I’ll never forget the contribution of one of the string principals- let’s call him Mr A. Mr A broke his right hand before the first session. He went straight to the hospital who told them they couldn’t set the broken bone until the swelling went down. They splinted the hand, gave him some pain medication and anti-inflammatories and he came straight to the recording session, his hand still bleeding from the accident. He played great, missed nothing- all day, three sessions. The next morning, they set the bone, and by afternoon, he was back in his chair, playing full out. If a student or an amateur wonders what kind of dedication it takes to be a great professional player, that’s a pretty inspiring example.

And what can I say about the Second Symphony? It’s compact (just over 20 minutes for a Beethoven-sized orchestra) but incredibly intense and inspired. The contrapuntal writing is staggering, but it’s all coherent and engaging (if you shape it and let it breathe). By the dress rehearsal/final recording session, the orchestra’s performance of it was becoming something to behold. At the end of that session, Phil himself said with surprised bemusement “it seems to have a sort of crazed Mahlerian grandeur to it.”

I’m so glad we were able to cap those two days of recording with a performance of at least the Second Symphony. This is when being in an orchestra really can mean something- when you’re no longer just calling up Doug or Jon and saying “dude, you’ve got to hear this live Coltrane disc” but reaching out to a whole concert hall full of new listeners and trying to let them discover that feeling for themselves. The orchestra, after two huge days of recording, played with astonishing power and involvement. There’s a great bit near the end of what functions like the slow movement (the piece is in a single movement but like lots of the great one-movement symphonies, still hints at the traditional four-movement structure) which I particularly remember. Phil pulls off one of those great compositional party tricks of building to a huge, sustained climax and then finding a way to keep going beyond it. Quite a way beyond it. Everyone is already playing fortissimo, and suddenly the page cries out “get louder.” You’ve given everything already, and the music cries out for more- not just more, but more “more.”

In the concert, I tried to do whatever a conductor does in these situations to find that “more” factor- perhaps you sweat and grunt a bit more, or you reach for the magic move. Maybe you open your eyes even wider. Often (always?), it’s about actually quieting yourself physically and emotionally, and showing something totally unforced, totally unsweaty. Sadly, most times you reach for the “more” in such a moment (which you only dare try when you feel the entire fate of the world depends on finding it) in concert, it’s just not there. Either the players don’t have more “more” to give, or don’t feel the internal motivation to find it. I can count the satisfying “more” moments of my conducting career on ten fingers. That was a big one- as big a wave of “more” as I’ve ever gotten in a concert. Who would have guessed a chamber orchestra of less than forty players could find that much “more,” broken hands, 15 hours of recording in 36 hours and all?

The five or so weeks since that concert have flown by faster than a bullet train in a flurry of projects, and suddenly, today I found out that we might have a first edit of the CD from Simon Fox, our producer, as soon as next week. Part of me is giddy with excitement- one makes a record because it is the record one wants to listen to. I’m sure this will be a good record- great music, fine musicians and a producer I trust to keep me from f*cking it all u.. I want to listen to it!

But can even the best record equal a moment like that in the concert? Experience tells me, probably not- even if that’s the take that ends up in the edit (our CDs together are not usually officially “live,” but we always record and often incorporate the concerts- the Scherzo of our Schumann 2 is essentially the concert performance without edits). There’s so much more to these moments than ones and zeros can possibly capture. The CD is probably bound to be a high-quality gentle let down. Hopefully one I’ll quickly get over as I get excited about all the new listeners who are going to discover this music through it.

In the end, it may be that we set out to create a “dude, you’ve got to hear this” record and ended up accidentally creating something rarer and more precious.

A “dude, you had to be there” moment.

___________________________

Update- July 6, 2014

At long last, the CD is released tomorrow:

Dude, you’ve got to hear it!

It’s great to read one more of your substantial, personal writings here. It’s been a while.