‘This traumatic experience…was linked to his First Symphony… This symphony thus spans the years of his ripening, the summer of his life… At that time he developed a stoicism, an ability to suppress his feelings and to tame the chaos within him, just as he mastered the art of channelling into a form the tumultuous, explosive natural forces of his music.’

Hans Gál: Johannes Brahms, His Work and Personality

Hans Gál’s First Symphony, like that of Robert Schumann, was not, in fact, his first symphony, but the endpoint of a long process of personal development, self-criticism and trial-and-error.

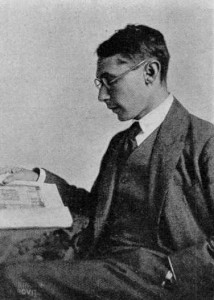

Born in Vienna in 1890, Gál had come of age in that capital of music, where symphonies by Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert, Brahms and Bruckner had all been brought to life. As a young man, he was able to observe Gustav Mahler’s rehearsals at the Vienna State Opera and was present for the premiere of Mahler’s Sixth Symphony. His principal teachers were Eusebius Mandyczewski, a close friend of Brahms, for composition and Richard Robert for piano, whose pupils included Georg Szell and Rudolf Serkin.

Gál thrived in early 20th-century Vienna, until the outbreak of the First World War on 4 August 1914, the day Gál would later say ‘the world collapsed.’ The outbreak of war was a traumatic experience for the young composer: Austria, as he had known it, was destroyed, and cultural life was affected in countless ways. Gál, however, was already showing the same ability to maintain his focus and productivity in difficult circumstances which would serve him so well in the 1930s and 40s. In 1915, he won the Austrian State Prize with a Symphony from 1911, but replaced it before the performance with another symphonic work, also subsequently discarded. That year, he was drafted into the army, but was hardly a natural soldier: ‘With my poor eyesight I was soon out of the troop that had anything to do with weapons. My rifle had become too dangerous for our own people. Well, in short, I was assigned to the administration troop and was relatively safely housed there. My main occupation at that time was to write an opera.’

The end of the war brought a mixture of relief and new challenges, and also triggered a major self-re-evaluation of Gál’s course as a composer. Gál was 28 in 1918, and had already composed an enormous amount of music, the vast majority of which he now withdrew. It is in the course of the 1920s that the mature Gál really emerges. The classical restraint, the wit, the transparency and the contrapuntal textures are all hallmarks of the voice he would remain true to for another sixty years.

For much of the next decade it was opera that primarily occupied and defined Gál. His first opera, Der Arzt der Sobeide (‘Sobeide’s Doctor’) was written in the last months of the war and premiered in Breslau (now Wroclaw) in 1919. Gál’s second opera, Die Heilige Ente (‘The Sacred Duck’, 1920–1), was a triumph at its premiere (conducted by George Szell) in 1923, and Gál promptly set to work on its successor, Das Lied der Nacht (‘The Song of the Night’), which was premiered in 1926. Die Heilige Ente remained in the repertoire of houses across Germany until Hitler came to power, after which all performances of Gál’s music in Germany ceased and Gál was dismissed from his position at the Mainz Conservatory.

So it was in 1927, at the peak of his fame and personal success, that Gál composed the work he would feel finally deserved to be called his First Symphony. Gál may well have felt he’d finally created a symphony worthy of the title, but his publisher initially insisted on calling it a ‘Sinfonietta.’ The work was completed on 7 November 1927 and the score submitted to the ‘International Columbia Graphophone Competitition’ jointly sponsored by the Columbia Record Company and the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna to mark the bicentenary of Schubert’s death. Gál’s new work was awarded second place in the Austrian section of the judging, behind Franz Schmidt’s Third (Kurt Atterberg’s Sixth eventually won the overall palm, and $10,000) and was subsequently premiered in Düsseldorf in December 1928. Since 1933, it has received just three public performances (in 1937, 1952 and 1970) prior to the one given by the current performers in 2013.

The First is the shortest of Gál’s four symphonies, the most extrovert in character and the most colourfully orchestrated. The opening Moderato fully embodies the qualities that would define his language over the next several decades: an inimitable melodic gift,

a virtuosic contrapuntal technique,

and a transparent and brilliant use of the orchestra.

The following Burleske opens with a marvellous orchestral stutter

before unfolding with mischievous rhythmic playfulness and biting, sardonic humor.

Gál’s lifelong fondness for the sound of the oboe is already evident in the beautiful and long-breathed opening solo of the following Elegie.

Gál would never comment on the inspiration for movements like this, insisting that the connection between life events and musical inspiration was an indirect and mysterious one, but he had witnessed and experienced great loss during the War years.

The final Rondo is a tour de force on many levels, a stunning orchestral showcase

and a declaration that the composer, like Brahms before him, had mastered the art of channelling the explosive, exuberant, joyful and occasionally tumultuous natural forces of his musical voice into a perfectly suited form.

Recent Comments