Imagine I suggest we go to the museum together to look at some art.

What do you first imagine we’ll be looking at.

If you’re like most people, you’ll first assume that we’re going to look at paintings. And maybe a few sculptures?

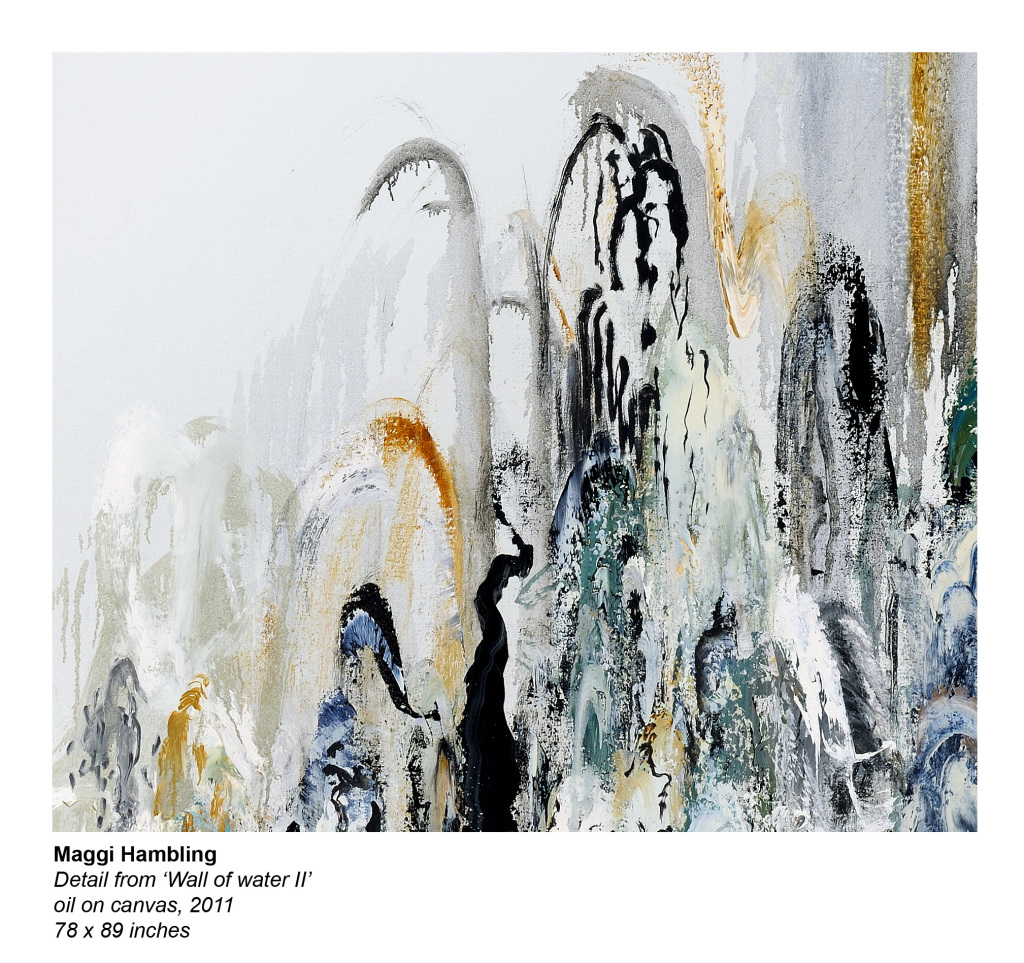

Paintings have been very much on my mind of late. The ESO just premiered an incredible new violin concerto by Deborah Pritchard based on the astonishing series of paintings, “Walls of Water” by Maggi Hambling. Not only was Deborah’s concerto written in response to Maggi’s images, those images were projected (on a grand scale) behind the orchestra during the performance. I’ve always believed that great music can and must succeed as music, without needing any sort of visual crutch, and Deb’s piece does more than work as pure music. However, this carefully calibrated integration of musical and visual works of art made a huge, positive impression on nearly everyone there.

The next morning, I had a bit of free time in London- a rare treat- and so decided to make my way to the Tate Modern. The Tate’s curation has had its highs and lows over the year, but it’s always an inspiring place to go. I’d been exploring the galleries for a good 45 minutes before I came into a space that was primarily devoted to painting. Having come there with paintings on the brain, this really struck me- how much eclectic, diverse and varied the visual art world is that we realize. Imagine a trip to a museum, and you think you’ll be looking at paintings, just as you imagine going to a concert and imagine you’ll be hearing a symphony. I went to the museum and saw sculptures, installations, videos, photographs, collages and more before I’d really seen a single good-old painting.

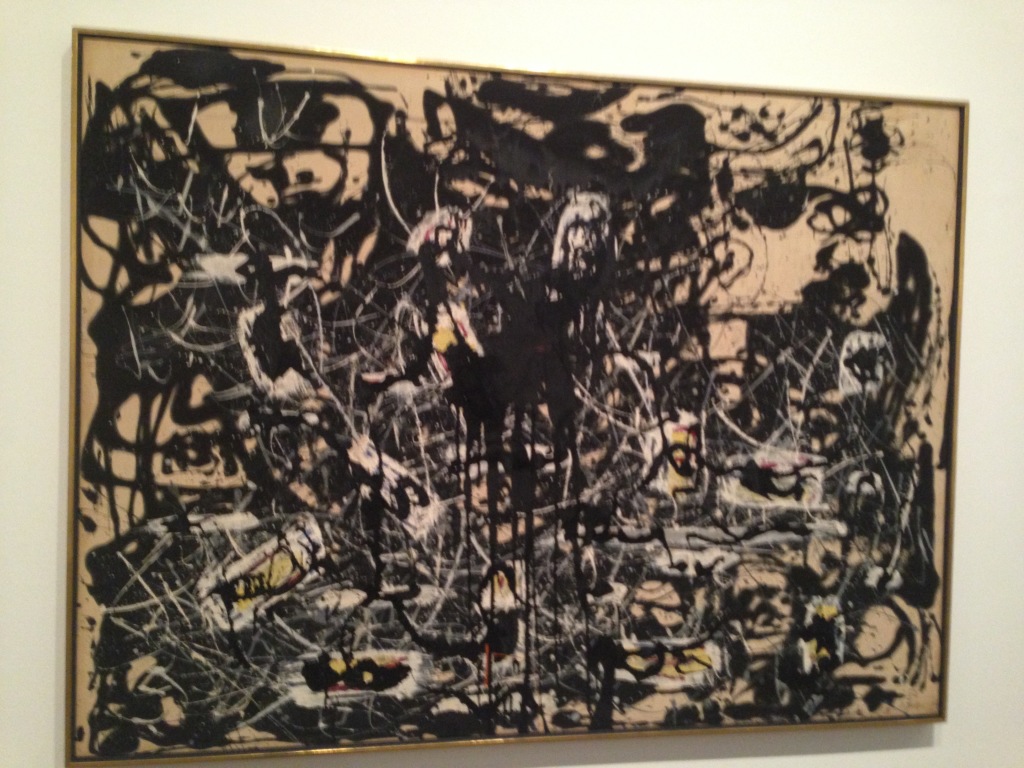

The first painting a ran into at the Tate Modern the other day. Looks wild, but check out those rectangles.

What a tribute to our colleagues in the visual art world that on a perfect, sunny Sunday in October, this vast facility was packed, literally packed, with thousands of people coming to look at this eclectic collection of art that is so experimental, so radical, so varied that seeing a painting really seemed like a blast from the past.

Not even sure what to call this- a few bits of wood leaned against the museum wall. But it’s cool, and dig the parallel lines and right angles. It’s as if the frame is all that’s left of the art.

Again I was struck, as I so often am, by the astonishing divergence of fortune between contemporary music and contemporary art. Contemporary art is POPULAR. People come out in the thousands to see all kinds of weird, wacky, challenging, dark, twisted, radical and uncomfortable stuff. People also spend a lot of money on it- contemporary art is big business. Not so in contemporary music- it remains a tough sell. Most people coming to the Tate seem to want to be challenged. A high percentage of people coming to a classical concert don’t. They crave more of what they know- familiar works, familiar genres, familiar forms, familiar languages.

But is visual art really as free from familiar forms, gestures and genres as we assume? However diverse the works were that I saw that Sunday morning, 99% of them shared one obvious formal device- they were all enclosed in squares or rectangles. Sculptures, paintings, collages, videos- all surrounded by parallel lines and right angles.

This beautiful re-imagining of the human form by Alberto Giacometti shows a man standing on an iron square, mounted on a bigger, wooden square

Physics makes a powerful argument for parallel lines and right angles- buildings constructed in this way tend to stay standing. Those with diagonal weight-bearing walls tend to have a harder time. Right angles and parallel lines are a primarily human construct. Nature does not produce many rectangles.

Nature abhors right angles, and so does Frank Gehry, but think about what shape most of the windows are in this building….

But even in more radically shaped spaces (the Tate, itself a former power station, is a study in right angles), art tends to exist in rectangles. Everywhere you look, you see parallel lines and right angels. Even when the art is chaotic and irrational, the context is, almost always, the simplest and most rational one can imagine.

Does the simplicity and clarity of the frame or the framing device account, in part, for the mass popularity of contemporary visual art? Does the lack of such clarity of context account for the lack of a mass audience for so much music written in the last 80 years?

Penderecki once said of Classical forms: ‘Logic. You must have exposition, you must have development … nobody can do anything better.’ Is the tonic-dominant relationship our right angle? Is the ABA form, or its big brother, the Sonata Allegro form our parallel lines? Surely such an analogue is too simplistic, but it’s one worth thinking about.

It’s been mostly bad news for music since 2008 or so, but I do seem to be having a run of concerts and projects where more and more of the time, the work making the biggest impact on much of the audience has been the newest one. I’ve seen players and audience members deeply moved by brand-new or nearly-new works by John McCabe, Schnittke, Deborah Pritchard, Robert Saxton, Philip Sawyers, Andrew Keeling and James Francis Brown to name but a few. Don’t forget Mr Penderecki, either. Some of these works have been written in wildy dissonant and experimental languages, using tons of extended techniques, others have stuck to traditional genres and a tonally-informed musical harmonic language. All those which have made a strong impact possessed a powerful originality of thought and a keen mastery of the fundamentals of compositional technique. Charlatans are not hard to spot in contemporary music.

This rectangle filled with angsty squiggles by Jackson Pollock looks crazy, but the form is incredible simple and logical.

On the other hand, I’ve done two new works by composers I really admire in the last couple of years that I, sadly, felt just didn’t work in the end. Both composers where just as technically accomplished as any of the musicians listed above- both have written other pieces I adore. However, neither piece seemed to work- the audience could sense it, we felt it on stage. Somehow theses pieces didn’t arrive, didn’t cohere, didn’t deliver- they just didn’t work.

Can a picture of a bus stop in Armenia be high art? You betcha, as long as it’s Ursual Schulz-Dornburg who takes the shot and puts it in a rectangle.

Is Sonata form the parallel lines of music? Of course not, but, as listeners and performers, we sense that the beginning and ending of a musical work represent the most powerful relationship in a piece of music. It’s more than a hunger to return to the tonic key- Mahler, with his progressive tonality, showed us that sometimes a piece finds closure without returning to home, and yet he, of all composers, also understood the deep, instinctive relationship between the beginning of a journey and it’s fulfillment. When a piece works, the line at the beginning finds its parallel in the line at the end- the ideas of the piece, their working out, and the shape of the piece find a satisfying and logical relationship.

“Logic,” said Maestro Penderecki. “Nobody can do anything better.” Exposition and recapitulation forming parallel lines, development lying at a right angle? What I find more and more with audiences (if you can get them to the venue in the first place) is that they can happily grapple with any musical language if they can perceive the structure of a work with the kind of clarity of function we perceive in the rectangle that frames a painting, a video, a sculpture or a new visual idiom, yet to be defined and realized, but, more likely than not, one to be found lovingly bracketed in parallel lines and right angles. The simpler and clearer the form, the more powerful the impact of the content. The more radical you can be.

Rothko showed us you could become one of the 5 greatest painters of the 20th c by painting rectangles.

That’s not conservatism- that’s finding a framework for originality that works.

Interesting stuff. Though I know I’m not the first to say this, I still think the modern art vs. modern music audience conundrum comes down, more than anything else, to the “captive audience” problem. Note that the captivity comes in two parts: 1) music proceeds exactly at its own pace – you can’t jump around within in, come back later – you’re stuck in the moment, which can be one of the best things ever if you dig the music, but if not…. 2) being physically captive in a chair (probably at least somewhat uncomfortable) and the strange social demands of being quiet (watch that cough, and don’t shift your weight because that chair is its own percussion section) when the body wants to move. How many galleries enforce anything like the kind of chair captivity that is standard in concert halls? (I love concert halls, and I appreciate the value of sitting and listening. Still…)

The second problem, in theory, can be helped by innovative presentation settings (though these bring their own sets of problems and really are no great solution), but the first problem is harder to solve. I’m an experienced musician with (I think) an adventuresome spirit but, as of now, still pretty conventional tastes. I make lots of efforts to listen to music I don’t (yet) love or “get,” but I am sometimes struck by a genuine kind of discomfort that I don’t think looking at “out there” visual art is as likely to cause.

For example, yesterday I decided to give Alisa Weilerstein’s recording of the Elliot Carter Cello Concerto a try. There were some moments that I thought were really exciting and even lovely – but there were others when the abrasively dissonant sounds actually hurt my ears. Listening was really painful, and it’s not like I don’t love lots of dissonant music – but I just couldn’t sort what I was hearing, and I had the strong urge just to turn it off. (In fairness, I was listening on a car CD player that likely didn’t provide the best sound – music like that usually sounds better live.) I stuck with it, but I can’t think of an analogous experience I’ve had in a museum.

Ironically, it seems to be that the more abstract visual art is, the less likely it is to cause that kind of discomfort – visual art is more likely to be painful when there’s some kind of representation of familiar images in disturbing contexts. With music, the more abstract (I guess meaning no apparent melodies or harmonies to hang on to?), the more likely the listener is to feel a kind of confusion that actually is uncomfortable. And even when the music isn’t literally painful, sitting and listening to something that one can’t “latch onto” (as you discuss with your talk of frames) can be really frustrating in a way that moving about in a gallery is not likely to be.

Am I saying that art should always be comfortable? No, but I think there’s a different dimension to the kind of discomfort difficult sounds and being trapped can elicit. It’s cliche, but you can always close your eyes (or look away) – you can’t just close your ears.

All of which is to say that it’s never seemed surprising to me that modern art is less threatening to audiences than modern music – they’re two very different animals and types of experiences.

Hi Michael-

Great comment and lots of interesting thoughts. Don’t know the Carter yet. I agree it’s not surprising contemporary music is often a hard sell, but it is a pity when great contemporary music is a hard sell. I don’t want to sound like a fuddy-duddy, but the “listener and musicians be damned’ approach some composers seem to have taken over the years has made it harder for many worthy voices to be heard with open ears.

Mr. Woods –

A friend gave me a link to this website and I’ve already thanked her. Always great to find an artist of any kind who writes well and thinks deeply (many of your older entries here are great fodder for those of us new to them).

As a painter I was interested on these particular observations—particularly since I haven’t used a right angle for over two decades. But I confess that, like Robert Mangold and David Row and so many others you could Google, my work is too often dismissed as “sculptural” or a hybrid of the two mediums. In fact most who broke out of the rectangle did so in the 70s (shaped canvas) and it’s now considered old hat. Nevertheless I take your point.

With so much new music I’ve been listening to lately, I find myself without a compass but yet, when sensing structure, suspect the composers may be falling back on traditional devices. Which is OK with me. So Michael Gordon, Georg Friedrich Haas, Alex Mincek and even late Steve Reich works seem to break up into familiar-seeming sections and use key changes to signal codas and conclusions. But these structures seem to have been arrived at organically and not a priori, and thus seem re-inventions rather than crutches.

Anyway, I plan to enjoy your posts from now on, and happy to find out about them!

A lot of the art you have here is not contemporary. Early-to-mid 20th century art IS art of a different time. Modernity, on the other hand, transcends time, as does what I like to call “real” art. (Haydn is a fine example of modernity, as is Robert Motherwell.) There is a lot of contemporary art that is as gimmicky and vapid as contemporary music, but the fact that viewers are not obliged to spend a lot of time looking at the gimmicky stuff, and can appreciate the monetary value of what they are glancing at, changes the way they evaluate the piece of art. Sometimes (or all too often) they are swayed by extra-artistic elements, like celebrity or “edgy-ness.” There is also the technological element, which is sometimes valued above technique.

I believe that people should demand from their art what they demand from their music: an open-ended relationship that constantly feeds the soul. As the soul becomes better and better fed, it becomes picky, and it demands higher quality and deeper emotional content.