(Disclaimer- I’ve broken my no-swearing rule in this post. Apologies for any offense. I think Haydn’s music merits a bit of good profanity)

Long-time Vftp readers will know that I’m quite the Haydn aficionado. Last Saturday, I broke a long, heart-wrenching dry spell since my last performance of a Haydn symphony with a very satisfying rip through the Master’s Symphony No. 44 in E minor, “Trauer (“”Mourning”).

A satisfying performance? Maybe that’s not quite the right description. I dare say I was satisfied, nay, even pleased with how the orchestra played it and how the audience responded.

But was I satisfied with the performance the way one is satisfied after a tasty and filling meal? Certainly not- far from being content that the experience had brought some kind of worthy closure to the project, I felt like I wanted to conduct the piece five more times right then. I wanted to gather the audience and the musicians at the foot of the stage and talk about the score for an hour. I wanted to record it, I wanted to sing it. Part of me just wanted to stand on the roof of a tall building and howl at the moon all night in honour of the genius of Joseph Haydn.

(Nicholas Kenyon’s interesting overview of recordings of Haydn’s Symphony no. 44 from BBC Radio 3’s CD Review. Kenyon has many interesting things to say about the piece, and all the recordings he plays are well played, but in none of them to get the feeling that everyone is giving the music everything they’ve got. To me, the music seems held at arms length by almost everyone)

I’d like to think that the gist of my reaction to the piece was similar to that of many people there (if amplified to a freakish level of intensity). Something about that performance felt very raw, very intense, very primal. I’m thrilled to say it was not a “nice” performance. It left me hungry for more rather than full and satisfied.

One thing I won’t be doing much of in response to that hunger is listening to recordings of the Haydn symphonies. Why? Well, with all the goodwill in the world, many of them don’t excite me very much. There! I said it.

More than any composer I can think of, Haydn has been saddled with a certain patina of earnestness that seems to have penetrated virtually everyone’s approach to his music. I’ve written about this before- about how the “Papa Haydn” image seems to have put a glass wall between us and the scores.

I’ve always liked Haydn. I’ve always liked conducting and playing Haydn. I’ve tried to make myself aware of all the historical and stylistic issues connected with playing his music.

Then, one day, I had my “fuck it” moment. I was rehearsing Haydn’s Symphony no. 92 (Oxford) in a cold, dark, dingy village hall on a rainy Sunday morning. One minute I was conducting a read-through of the first mvt, taking note of obvious problems to fix and having a think about what the “right” thing to do was in terms of phrasing, tempo and vibrato. Then I thought: “fuck it.”

Some little voice inside me pointed out that it seemed a little perverse that almost all the music written by a man widely, if not universally, acknowledged as one of the 10 greatest composers of music who have ever walked the planet, tends to be heard 99% of the time in very nice performances by very nice people, with almost no emotional range- a dynamic range from mp to mf, moderate to sprightly tempos, and sounds neither too smooth nor too rough. Everything is so fucking charming, so fucking elegant, so fucking nice.

I once read an article called “Haydn- the Shakespeare of Music.” It’s a surprisingly apt comparison. Can you imagine King Lear spoken entirely in gently genial tones? Could you endure Hamlet staged entirely in a tea party? How about a Romeo and Juliet in which the Montagues and Capulets conversed politely over scones?

Anyway- back to my “fuck it” moment. I stood there in that perennially damp, grey rehearsal hall and thought: what if this giant of music actually wrote music of huge, immediate, staggering range? What if I’m not supposed to tone down the fortissimos and smooth out the contrasts? What if the scary bits are not supposed to sound “cute scary” or “Classical scary” but actually “scary-scary?” That morning, I gave myself permission to rehearse the Oxford free from fealty to any stylistic authority or creed beyond an honest and creative engagement with Haydn’s text. By the end of that rehearsal, I no longer liked conducting Haydn. I loved it.

So began what has been one of the most rewarding threads of my career- especially when working with colleagues willing to take chances and experiment. There have been moments of frustration- I remember a week with a group of brilliantly gifted conservatory students at a great American festival in which I just couldn’t seem to persuade them to stop tickling and tap-dancing their way through the piece we were working on. I wanted them to play like Vikings, they wanted to play like society ladies. On another occasion I was doing one of the zaniest middle symphonies and the concertmaster just seemed to have a “blue screen of death” moment in the concert. She just couldn’t seem to handle the insanity of the music and totally shut down. Mostly, it’s been great. I knew the musicians of the Orchestra of the Swan and I would get on just fine when David LePage and Simon Chalk (the concertmaster and principal second) started stamping their feet and grunting on the first page of our performance of the Farewell on my very first concert with the orchestra.

(I once worked with a violinist who couldn’t handle the truth about Joseph Haydn)

Last week’s performance of the Trauer came at the end of a serious, quasi-Remembrance Day programme. The concert opened with Ravel’s “Tombeau de Couperin,” continued with Vaughan Williams’ “On Wenlock Edge” and Butterworth’s “On the Banks of Green Willow” and finished with the Haydn. I know there were murmurings before the gig about how unlikely it seemed that a nice bit of Haydn could possibly form a fitting conclusion to such an emotional programme. Surely it would be an anti-climax?

There are all kinds of measures of what makes a special concert, and accuracy and polish are not to be underrated or taken for granted. On the other hand, one also learns over time that it’s not that often that you really feel that pretty much everyone onstage is giving everything they’ve got. Attacking the fortissimos, ripping into the accents. I’m happy to say on this occasion, everyone was. The contrapuntal episodes in the last movement felt like a true barrage, an onslaught. The end of the symphony was shocking in its violence.

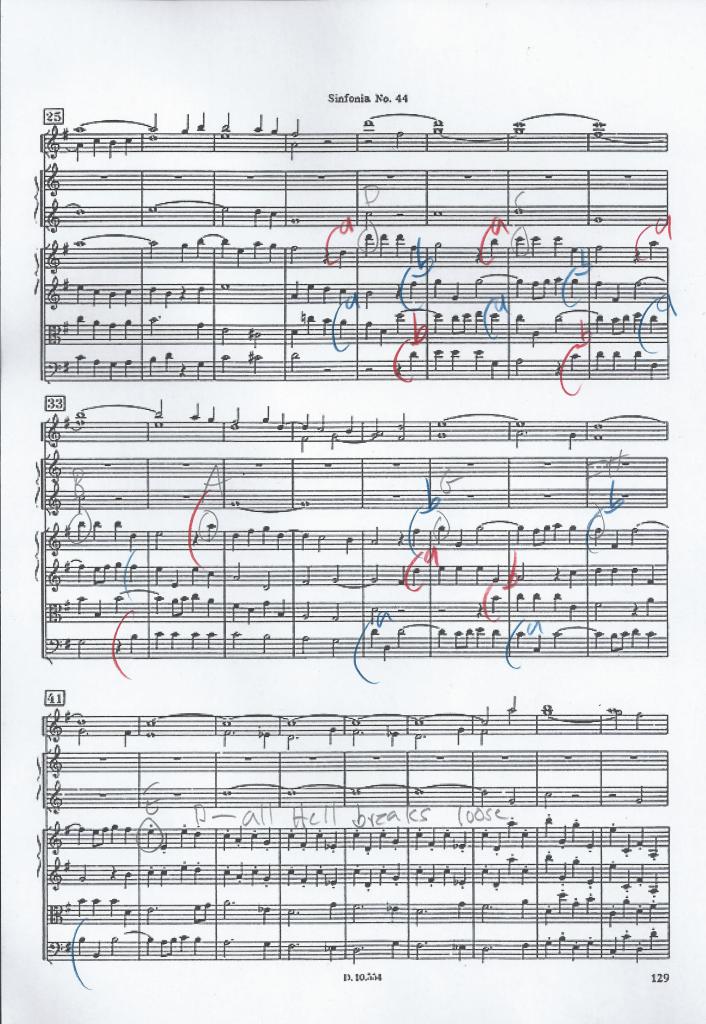

I marked up this contrapuntal episode in the Finale of the Trauer just to show how wild and intricate the music can be. Note how there are two imitative processes going on at the same time (including a lovely canon at the 7th), moving in sequence descending sequence, and then the distribution of parts switches around without breaking the first violin’s stepwise descent from their high D. The next page is every crazier…

I stood there in a cloud of rosin, smoke, sweat and ozone, dumbfounded by the sheer badassery of the music we’d just embraced for the last 25 minutes.

Fortunately, my wife found me before I could make my way to the roof to begin howling at the moon in celebration.

Of course, Haydn’s music can be nice, and pretty much nobody before or since has been able to write music with the kind of charm and elegance he could put on the page. The point is that, masterful as he was in the realm of charm and elegance, he was just as masterful at conveying rage, anguish, irony, insanity, joy, hope, fear, lust, menace, suspense, tenderness and violence.

I realize this post may come off a little self-congratulatory, so let me clarify- I’m not saying “I’ve got this shit figured out and you should do it like I do it.”

Quite the opposite.

Since my “fuck it” moment on that long-ago Sunday morning, I’ve realized that nobody has this shit figured out- the more you get to know Haydn, the more you realize he’s in a different league to the rest of us. Nobody has this shit figured out.

Maybe the issue is that Haydn’s music is so modern, so radical, so outrageous (and so relatively rarely played) that most of us don’t even know where to start with it, so we reach for expert opinion and received wisdom. The received wisdom on Haydn is that his music is very nice. The simple gist of this blog post to listeners and performers alike is that, as I’ve said many times before, in this case, received wisdom is the tiniest edge of the truth. The received wisdom is about 3% truth and 97% unhelpful horse-crap.

There’s a lot of charming music in Mahler, but (as far as I know) nobody tries to import the kind of easy-going Gemutlichkeit vibe of “Ging heut Morgan übers Feld” into the Finale of Mahler’s Sixth Symphony. Why should we try to paint a Sturm und Drang symphony of Haydn in the same Rococo pastels we use for the C Major Cello Concerto?

When I think of Shakespeare, I tend to think of the tragedies, but there’s more to the Bard than misery and death. What makes him Shakespeare is the astounding completeness of his observation of the human experience- when he writes a funny scene, it’s really funny, when he writes a love scene, it’s full of passion and electricity. Haydn’s range on the page is much the same- we just tend to read too much of his music in the same tone of voice. Yes, he can do reason, he can do charm and he can do wit, but he can do everything else, too.

The Trauer is a work conceived in fire and bathed in blood. The next Haydn symphony I conduct might be a hymn to the glory of the universe or a rumbustious depiction of barnyard animals at feeding time. Our job as interpreters is to try to figure out what he’s saying and bring it to life, not to force every dynamic change through a safety valve.

__________________________________________

More thoughts on the Oxford Symphony from Vftp

Haydn the Subversive

Back to Oxford

Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag

Other Haydn stuff you should read

Haydn the Yurodivy

Haydn in the Oregonian

How Haydn Stacks Up to the Greats

Haydn- More Talented than Mozart

Haydn- Smarter than Brahms

Haydn- More fun than Mahler

https://youtu.be/HOCPmdSiH3c

Ken-

I’m reminded of a brief conversation I had with Jim Smith following a fabulous performance of #88 with the UW Chamber Orchestra about a year ago. He said, “I think I may have overplayed the jokes a little much.” My retort, “I’m not sure that’s possible.

I got hooked on Haydn the first time I heard “Passione.” It was so dramatically different than the “Papa” I thought I knew. Now to just get hold of an orchestra to play it and many more….

Cheers!

Via FB

*head banging and howling with you at the moon* The very best oboe writing of the period. In fact, probably ever (ok, not including Schubert). It plays like he’s writing for the oboists he’s partying with, crying over beers with, getting frustrated by, sharing gripes and moans with, enjoys the craic with, and whom he respects as fellow creatives in their own right. Absolutely brilliant. Lies perfectly on the instrument, and he is a rare beast in that he credits ob2 with the ability to work solos independently of ob1. Huge gratitude, Herr Haydn, from an Ob2.

Via FB

YES! Its always been a source of irritation to me that the music gets hijacked by people hoping to contain or control it into civility. I call it “The Dinner Party Effect.”

Glad to know that you are still itching to howl at the moon!

Via FB

have you heard any of Scherchen’s Haydn recordings? They’re not all successful but he definitely eschews the ‘Papa Haydn’ model

Via FB

If you want to come join me on the roof I’ll be up there howling!

Via FB

I think we all like that you like Haydn, Ken, and I think as a conductor, even one far more prepared to be widely ‘read’ in recordings than most, you’re more than entitled – expected even – to find that your predecessors have not gone where you would travel. How, otherwise, could you kindle that fire for Haydn for yourself, not to do it right, but to do it better?

However… I do think performers have had personal and passionate things to say about him, maybe outside the usual tracks of tradition. Do you do Thomas Fey (he’s on Spotify if you want to check him out)? I think he’s a superb Haydn musician for our times. Certainly he’s making the only complete symphony set that goes even halfway to treating each symphony on its own terms and not belonging to some arcane set of grammar. NK liked Fey in his survey though found aspects of the recording eccentric, and I can see why but, as you say, you have to take a view on this stuff. You can’t just play it.

Then there’s 103, to which I’m listening intensively at present. The first recording was made by the Saint Louis SO and Golschmann, in 1935. The first movement’s the quickest on record (that I’ve been able to trace); absolutely unrelenting; never for a second taking its imaginative leaps for granted. Henry Wood doing No.45 in 1934 in similarly unsentimental

Hi Peter- I do like Fey. His performance is appealingly mad in a well-thought out way, although it sounds to me like the strings are playing “a la period’ on a modern setup which I find creates problems (maybe I’m wrong and I’m just wanting a warmer, grittier sound). To imitate the clarity of gut strings and transition bows, one ends up holding back and lightening up in ways I don’t think you’d have to on old instruments, and the sound is a little bright and edgy. The total non vib thing seems a little simplistic to me, too. I tend to love Harnoncourt’s Haydn, and his band seems to really play with wild abandon- they sound they get is not trying to imitate old instruments, it is old instruments. What a pity he’s not recorded the Trauer (at least as of NK’s survey). Thanks for the tips on the Wood and Golschmann, neither of which I know. In any case, I was careful to say “many” Haydn recordings (not even “most,” I point out) , and not “all” by any means, leave me cold. Good to hear from you and enjoy your immersion in 103.