It’s not often that something from the New York Times Op-ed pages gets you thinking about music for children, but a blog post by Paul Krugman this week reawakened a line of thought that had been simmering away in my subconscious since the premiere last week of the new orchestral version of my setting of The Ugly Duckling.

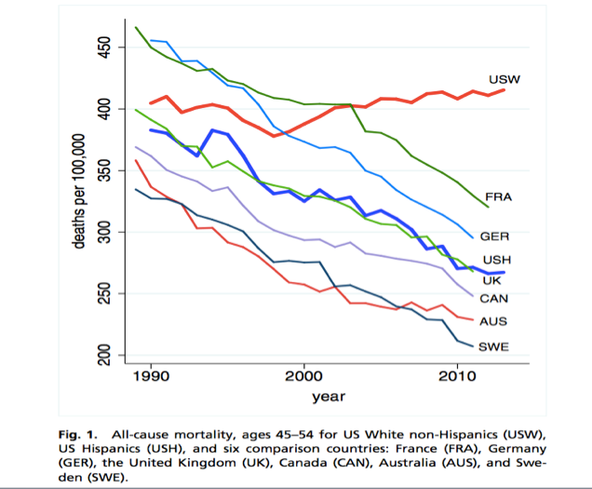

Krugman’s column (interestingly, the right-leaning NYT columnist Ross Douthat picks up on the same study here) examines a recent study which seems to document a genuinely terrifying malaise spreading across the American heartland. White Americans, a group of human beings who start their lives with more advantages than perhaps any other social or ethnic group in history (other than the European aristocracy, perhaps), are literally dying of despair. People are dying at their own hands, dying of drink, dying of drugs, dying of self-inflicted diabetes.

Times are tough all around the world- tougher than they’ve been in more than 75 years. But while economic inequality, political dysfunction and concerns about war, terrorism and security can be a toxic brew, I am concerned there is more at work here, and the problems reach back to the comfortable and prosperous childhoods many of these people now dying of despair grew up enjoying in the 1980’s, 90’s and 2000’s (* see below). I’ve written before about the toxic effects of what I call “junk culture” and it seems that what we’re seeing now in America is a terrifying metastasis of a lifetime’s exposure to “entertainment” which rots the brain and poisons the soul.

(Imagine a modern comic story in which the challenge for the hero is to restore vowel sounds to the human race)

Children’s literature and entertainment underwent a seismic shift during my own childhood in the 1980’s. One need only look at the changes that took place in the output of any of a number of popular children’s franchises, whether they be Scooby Doo or Superman. In the early 80’s, entertainment became far more starkly divided into material for boys or girls, and in both arenas, the tone changed enormously. Plotlines became notably more simplistic, and cartoons started repeating material after commercial breaks, as though kids couldn’t remember what they’d just seen (this technique is now the mainstay of all media, from NPR to the BBC to Fox News- we must constantly remind the view what they’ve just seen and tease them with what they’re about to see). Language became purely functional, and of secondary importance at best. Gone is all the wordplay and wit one can find in children’s entertainment from the 20’s through the 70’s, with sarcasm and snark standing in for sophistication, humour and insight. Today’s Batman is a mono-syllabic psychopath, his enemies screaming madmen. In boy’s entertainment, the tone of everything has become darker and more violent, but the violence has became strangely bloodless, and the plotlines lacking in almost tension or sense of consequence. For girls, stories and shows made in the last 35 years became primarily about social standing. The tensions of high clique-ism in almost any girls’ show, from Strawberry Shortcake through to Saved by the Bell, are just as psychologically- violent and banal as anything in a 1990’s era Superman cartoon. To summarise the changes we see that-

- We began asking much less from viewers and readers in terms of attention span and ability to process language, stay engaged with a story through moments of high tension, remember plot or understand complex messages

- Violence, both physical and social (teasing, exclusion, pressuring) becomes more pervasive, but largely consequent-less

- Viewers and readers are spared anything that might be genuinely upsetting, but exposed to much that is desensitizing and which normalises things which should not be normalised.

- Commercialism and social standing is shown as the path to happiness. Buy the toy of the show, and you will be happy. Being normal will make you popular, and being popular will make you happy. If you’re not popular, you’ll never be happy.

Nowhere is this change more obvious than when one looks at classics of children’s literature of the past. Three years ago when I first had the idea to set The Ugly Duckling to music, I only really knew the story from the Danny Kaye song and the odd modern adaptation. When I finally read Hans Christian Andersen’s story I was completely overwhelmed by it and was determined to set it to music as faithfully as I could. It’s a deeply upsetting work full of pain, heartbreak, exclusion, violence and loneliness. Every time we’ve done it, I’ve been braced for challenges from people saying it’s too dark, too upsetting or too long. Unlike a modern superhero film where the protagonist walks through a blizzard of bullets and emerges unscathed, or destroys a city battling the baddies without hurting any identifiable people, every act of cruelty and misfortune is deeply felt by The Duckling. Andersen constantly reminds us of what the main character is feeling, not just what he is doing, and most of what the Duckling is feeling is pain and despair. In the story, Andersen pulls no punches about where this all leads- the story culminates in the Duckling’s attempted suicide. Compare this to so much children’s entertainment in which a character is socially excluded from the popular gang because she wears glasses for a few minutes, gets a makeover and then lives happily ever after as “one of the in crowd.” The Duckling in the end isn’t welcomed back by his birth family, he doesn’t get invited to a party at the popular ducks’ house, the turkeys don’t apologise for biting him. He is welcomed into a new community, but remains excluded from the one in which he grew up. His salvation isn’t in changing his clothes or winning over his adversaries, it’s in discovering his true self. I recently read a fascinating interview with J.R.R. Tolkien (**see below) in which he dismissed Andersen as a simplistic moralist. I certainly don’t see that in Duckling. The message seems far from the “don’t worry, everything is always fine and all problems resolved at the end of the episode (BUY THE TOY!)” simplicity of modern children’s entertainment. Instead of telling the reader that everything will be fine, it seems to warn us that life is anything but fine, that life is full of pain, disappointment, loss and loneliness. The comfort of the story is not that Andersen says the problems of life can be solved (it appears they can’t be), it is that it teaches us that they can be survived. It teaches that your only real hope is not what you do (nothing the Duckling does in the story improves his condition, he only manages to extract himself from one perilous situation after another. It’s a story about running away, not fighting back.), but who you are, and that is enough.

I was encouraged speaking to my friend Sebastian at the concert to hear that at the local Steiner school in his village, they spend a lot of time exposing children to the work of Andersen and the Brothers Grimm. Also on the programme last week was Tom Kraines’ fantastic setting of the Grimm Brother’s Hansel and Gretel, another startlingly dark tale. The last part of the story with the kids imprisoned in the gingerbread house is genuinely terrifying- strip away the shtick with the candy and the archetypical witchy old woman and you have everyone’s worst nightmare of child abduction and attempted ritual murder. Upsetting as this is, the family dynamics that Hansel and Gretel face throughout the story are possibly even more troubling. Their father’s wife (in some versions their mother, but often described as their stepmother) is genuinely evil, pressuring their father to “take them into the forest and leave them there.” He’s obviously not much better, abandoning them twice.

(The opening of Tom Kraines’ setting of Hansel and Gretel performed by Auricolae. David Yang- narrator and artistic director, Diane Pascal- violin, KW- cello)

Fairy tales are dark on purpose- they allow children to prepare themselves for the challenges and terrors of life in psychological safey. By turning the protagonists into barnyard animals, as Andersen does, or cloaking real-life horrors in myth and candy as the Grimm Brothers do, we allow children to engage with deeply troubling but not-uncommon problems. Almost everyone who saw the movie as a child remembers how inconsolably upset they were when Bambi’s mother was shot, but imagine how much more traumatic the experience would have been if Bambi and his mother were depicted as human? Of course, thankfully only a tiny handful of young children have to deal with the sudden and violent death of a parent, but the realisation that one could lose a parent is potentially one of the most traumatic moments of childhood, and one that all children have to face. I can remember the cultural moment when everyone realised that malign fairy tale of step-parents is largely unfair and grossly stereotypical- most step parents are loving and committed. However, I also knew a little boy growing up whose stepfather subjected him to a childhood of shocking cruelty, lavishing praise and affection on his birth children, while either ignoring or mocking this kid for most of his life. Fairy tales often deal in archetypical characters who are necessarily exaggerated and over-simplified, but they allow authors to depict the very real dark side of humanity in the context of a short and comprehensible story.

Importantly, the long-suffering protagonists of the best classic children’s stories are not the only vivid, realistic or multi-dimensional characters. Not every child will see themselves in The Duckling- more than a handful will recognise more of their own nature and behavior in the brothers, sisters and neighbours who taunt and humiliate The Duckling on the playground. His birth mother starts as a loving figure, and even steps in to protect him from his peers, but as soon as his presence jeopardises her social standing, she abandons all responsibility for him. Hansel and Gretel’s parents act with astonishing disregard for their children’s well being, but they are driven by starvation and poverty. These stories teach us that normal people, convinced of their own righteousness, are capable of inflecting terrible suffering on others. They teach empathy, where so much modern children’s literature and popular culture actually says that being accepted by bullies into their cliques and gangs is the true measure of one’s success in life.

For more than a generation, we’ve fed both children and grownups a toxic stew of diversionary, dehumanising, commercialistic garbage that teaches nothing, that prepares one for nothing, that helps you understand nothing. The terrible increase in death by suicide, drugs and alcohol we’re now seeing in America is being compared to the state of affairs in Russia following the breakup of the Soviet Union (Krugman writes “As a number of people have pointed out, the closest parallel to America’s rising death rates — driven by poisonings, suicide, and chronic liver diseases — is the collapse in Russian life expectancy after the fall of Communism.”). The economic setbacks being endured in America now are not to be belittled, but must rank as laughingly minor compared to what happened in Russia in the early 1990’s, yet we’re seeing a similar epidemic of hopelessness. Even the distress faced by those in the former Soviet Union in the early 90’s were less dire than what their parents and grandparents endured across the first half of the 20th C. People can endure much worse and still fight fiercely for survival. White Americans are the only racial group manifesting this sort of large-scale self destructive despair, and yet it’s obvious that, as a group, they’re better off than African-Americans, Hispanic-Americans or almost any other subgroup you care to think of.

What the two countries do share is that they are societies in which the primary motivating factor of most public discourse is manipulation. Whether it is propaganda intended to shore up support for a dying communist government, or advertising, or faux news intended to rally support for a corporatist political and economic agenda, being saturated with messages calculated to control people’s behaviour is incredibly damaging over time. On the other hand, cultures that celebrate literature and learning seem to be remarkably resilient in even the most horrific circumstances. I would recommend everyone reading this to pick up Hans Gál’s Music Behind Barbed Wire, which is an amazing document that shows how music, learning, literature and social engagement can empower people to cope with shocking situations.

Fairy tales teach us to look within for strength in difficult times, where so much of media if the last 35 years tells us to buy, fight or blame our way to happiness. How is one to find happiness when you have no money to spend or there’s nothing left to buy, or nobody else to blame? No wonder we have so many people running around our cities carrying guns. To an outsider, the insanity of the behaviour seems painfully obvious, but these are people who spent their whole childhoods being taught that guns solve problems and that the bullets never hit the main character, and we all think of ourselves as the main character in the movie of our own life.

Both The Ugly Duckling and Tom’s Hansel and Gretel grew out of my friend David Yang’s “Auricolae” project. It’s something I’ve been very proud to be a part of. Most “classical music for children” is anodyne rubbish- music drained of all power tied to stories sapped of all importance. It’s a welcome reminder that we don’t have to be too sentimental about an idealised litery past- there’s still plenty of room to create new and interesting children’s literature that is of our time. Meanwhile, I would be thrilled to death if my little piece helped more members of my children’s generation to get to know and think about Hans Christian Andersen’s literary masterpiece, but in today’s climate, I don’t expect it to reach more than a few hundred sets of ears. I don’t think it’s likely we’ll ever see Andersen’s masterpiece depicted honestly on film. I can’t imagine a bunch of suits at Disney ever greenlighting it without first gutting it. The Duckling’s tale of heartbreak, bullying, isolation and attempted suicide would surely ruffle too many feathers.

______________________________________________________________

Consumerism sucks. Buy our CD!

*This study is particularly unnerving as it deals with people aged 45-54, most of whom are old enough to have grown up through the transition from one era of children’s entertainment to the current one and thus to have had at least some exposure to healthier content in their childhood. The prognosis is sure to be grimmer for those now 15-45, who’ve grown up in a far more cynical and isolating world. Also, the social cost of the last 14 years of perpetual war are not accounted for in this study- we know depression, addiction and suicide are epidemic among veterans, but much research needs to be done to understand just how widespread the problems are and how they affect veterans’ families and communities.

** I grew up as a huge fan of Tolkien and the Lord of the Rings. When I returned to the books as an adult, there was much I found shocking and disappointing, but I found two things really compelling and profound. First, I’d kind of forgotten that Frodo ultimately fails at the moment of truth. It was only because of his earlier mercy towards Smeagol that The Ring is destroyed. Second, and even more telling, is the touching way in which Tolkien shows the price Frodo and Bilbo pay for their adventures. When we re-encounter Bilbo at the beginning of LOTR, he’s a profoundly changed and damaged hobbit. At the end of LOTR, Frodo seems tormented by melancholy- in the end, he’s been so changed by what he’s experienced that a hobbit hole no longer offers the comfort guaranteed in the first paragraph of The Hobbit.

In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. Not a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell, nor yet a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat: it was a hobbit-hole, and that means comfort.

Recent Comments