Antonin Dvorak- Stabat Mater, op. 58

Dvorak began and completed his great setting of Jacopone da Todi’s 13th century poem Stabat Mater under a cloud of great personal tragedy. In 1875 his oldest daughter Josefa died only days after her birth. The grieving Dvorak turned to the ancient text of the Stabat Mater, seeing in its evocation of Mary’s grief at the death of her son a portrait of parental love and pain that he related to on a most personal level. He completed an outline of the entire work, but set it aside before finishing its orchestration and the working out of details to work on other pieces. Many scholars believe that the piece’s connection to Josefa made work on it too painful for Dvorak to complete the project at the time.

However, tragedy struck again with even greater cruelty only two years later. In August of 1877 his second daughter Ruzena, then a toddler, died when she drank from a bottle of phosphorus used to make matches. Only weeks later Dvorak’s three-year-old first-born son Otakar died of smallpox. The now childless 36-year old composer returned to the Stabat Mater sketches and completed the work within a month. Although now something of a rarity, it was one of Dvorak’s most popular works during his lifetime, and was performed under the conductor’s baton at the Royal Albert Hall with a chorus of over 600 singers:

“We had our first rehearsal with the choir at the Albert Hall on Monday, a superb building that can comfortably seat as many as 12,000 people! When I appeared on the rostrum I was welcomed with a long, thunderous applause, and it was a considerable while before everything calmed down once more. I was profoundly moved by such a sincere ovation, I couldn’t speak a word; there would’ve been no use in it since no-one would have understood me. […] The head of the association which performs oratorios exclusively, Mr Barnby, who conducted the Stabat mater last year, has studied and rehearsed everything wonderfully, so the rehearsal went very well. The following day we had the rehearsal with the orchestra, and the soloists in the afternoon – London’s finest, I might add, in particular, the tenor and alto have beautiful voices. But I must briefly mention the size of the orchestra and the choir. Please, don’t be alarmed! There are 250 sopranos, 160 altos, 180 tenors, and 250 basses; the orchestral sections were also impressive: 24 first violins, 20 second violins, 16 violas, 16 cellos, 16 double basses. The impact of such a strong ensemble was indeed exhilarating. I can hardly describe it. […] [during the concert] as soon as I stepped up onto the podium I was greeted by a stormy applause from an audience of about 12,000. After each movement their fervour increased and, at the end, the clapping was so loud, I had to take several bows, again and again. The orchestra and choir were also fervent in their applause, showering me with ovations. In short, I couldn’t have wished for a better outcome. All this has given me the conviction that a new and, God willing, more auspicious time has come for me here in England which, I hope, will bear good fruit for Czech music and culture in general.” Dvorak’s letter to his friend Velebin Urbanek, March 14, 1884

The finished piece stands as one of the towering monuments of choral music. There have been other great musical settings of da Todi’s poem, but Dvorak’s is by far the longest and most serious, set in 10 movements for a large orchestra, chorus and four soloists. Although conceived and written on a massive scale, Dvorak’s setting of the Stabat Mater seems to focus primarily on two very personal aspects of the poem’s emotional world, those of grief and of solace.

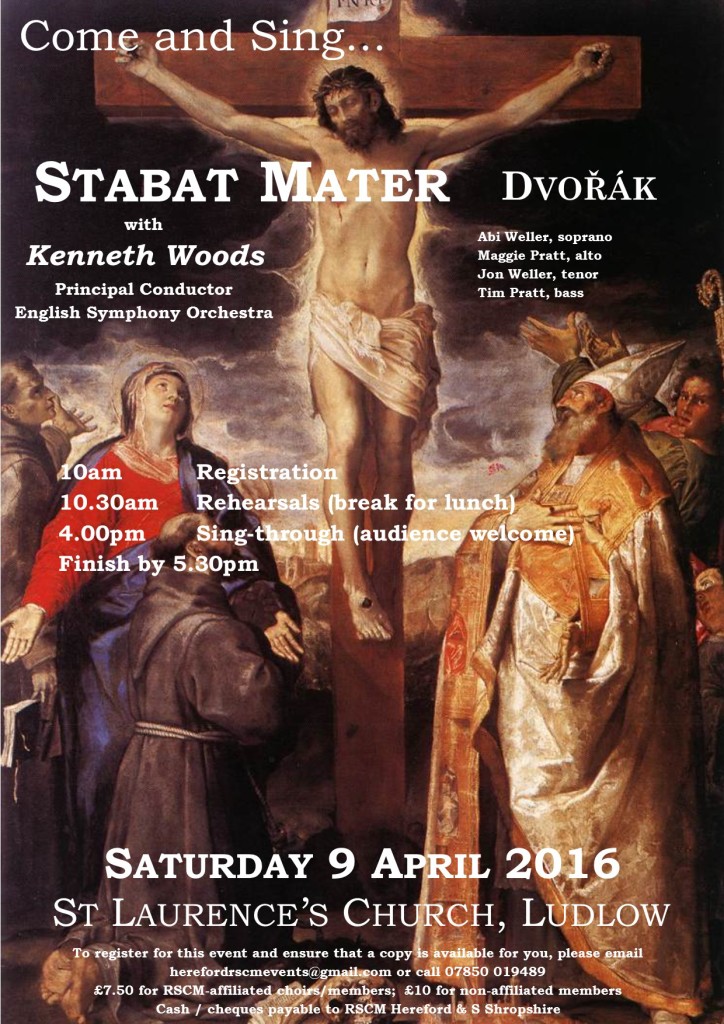

The work begins with the orchestra alone playing undulating repetitions of the single note f-sharp. Composers from the Renaissance on, including Bach, had often used the sharp sign – #, as a reference to the cross (in fact early texts called the sharp sign a cross). Knowing this, one can’t help but see in this opening the stark vision of the cross and Jesus in his final hours. The first moving notes heard are a descending, chromatic line, played first in the violins then moving from section to section. This lamenting theme may be an evocation of Mary’s falling tears as she weeps at the sight of her son’s suffering. The orchestra builds to a shattering climax, then fades and finally the chorus sings. Dvorak sets the first line with only the tenors, perhaps here the voice of the observer or narrator. The chorus develops the material set out by the orchestra and builds to the same climax on the word “lacrimosa” or “tears.” Finally in the middle section the four soloists join for what becomes a great dramatic scene. The final section is a recapitulation of the opening followed by a stately, hopeful coda.

The first movement is by far the longest and most emotionally complex in the work. Movements 2-9 each seem to meditate on one aspect of Mary’s grief, or the poet’s longing to give solace to her, or to share Jesus’ suffering. The second movement is for the full quartet of soloists and Dvorak uses the mournful english horn to emphasize the feeling of lamentation. The third movement is a dirge-like march for the chorus and orchestra. Some hear in its repeated C minor chords the trudging steps of the march to the crucifixion. The fourth movement is a great operatic scene for the bass soloist. This is Dvorak at his darkest and most tormented. However, it is in this movement that Dvorak also gives us one of the most stunningly sweet moments in all the work. On the words “Holy Mother” the women’s voices intone a simple chorale melody that can’t help but be heard as the voices of angels. The fifth movement, again for chorus and orchestra, is built on a serenely flowing, infinitely simple melody, interrupted in the middle by one of the few truly angry moments in the piece. Is this the music of Dvorak the father, exhausted from comforting his ailing and grieving family, finally releasing his pent-up anguish? In any case, the outburst is short-lived and the movement concludes simply and peacefully.

The sixth movement is a straightforward, almost lullaby-like melody sung alternately by the tenor soloist and the men of the chorus. It is Dvorak at his most direct, using the simplicity of folk-styled music to communicate on the deepest of levels. The seventh movement is the only one to feature a great deal of a cappella singing. The directness and innocence of the choir’s music is contrasted with a great, arching and longing melody in the strings. The eighth movement is a duet for soprano and tenor of incredible tenderness and deep feeling- in the middle section we find ourselves back at that stark sound of f-sharp. It as if Dvorak is forcing these two voices of comfort to face the horror of the cross. Finally, the ninth movement is a somber, march-like aria for the alto soloist, with reference made to the marching theme of the third movement. Now the theme is treated in an even more somber manner, with the pulsating rhythms replaced by a sobbing, almost desperate lyricism.

Finally, in the tenth movement Dvorak brings us to the end of this great meditation and voyage. In it, all the grief and all the tenderness expressed in the previous nine movements are surpassed in an embrace of the joy of transfiguration. The movement opens as the piece opened, with the stark, eerily compelling f-sharps in the orchestra. The four soloists then sing a lamenting restatement of the music of the second movement, which evolves into a restatement of the main themes of the very first movement. He has brought us full circle, back to where we started, but now chorus and soloists sing “Let it be that the glory of paradise is granted to my soul.” The massive crescendo first heard in the first movement on the word “lacrimosa” is now repeated on the word “paradisi,” and at the climax Dvorak arrives not on the anguished scream of the diminished chord he used in the first movement, but on a radiant G major chord, with which the work finally throws off the burden of grief once and for all. Freed at last of anguish, the soloists, orchestra and chorus burst forth in the first and only really fast music in the piece, a beautiful, almost ecstatic toccata on the work “Amen.” The work ends with one last, majestic statement of the very first theme of the piece, that unmistakable descending melody, heard now in D major, the key used by Bach and Beethoven to depict heaven in their own works. Instead of the opening words of the poem (“The mother stood weeping, grief stricken”) we now hear only one final “Amen.” Paradise attained, Dvorak has created a portrait of grace and peace so compelling, it can’t help but give comfort to all that encounter it.

Copyright 2003 Kenneth Woods

This piece is fantastic. We did it earlier this year at UBC and it was an amazing experience.

I have a question about it though that I noticed during rehearsals but didn’t have time to ask about. In the 4th movement, the chords from the opening return at the end of the movement, except as an echo of the beginning. Do you know if there’s any significance in this textually or prose wise?

Also, our conductor mentioned that the 9th movement was based off the Baroque/Bach tradition of having the alto soloist speaking to God as the voice of the people, which could also tie in with the traditional elements like the # sign meaning a cross, and the D major key at the end.

Hope your season and holiday break are going well.

Sincerely,

Bryan