I spent my May Day on a flight from London to Philadelphia this year, which isn’t much fun, but is certainly better than spending a flight from London to Philadelphia calling out “May Day!” I left home with a knot in my stomach and an ache in my heart- since our kids were born, I’ve tried very hard to keep business trips to about a week at the most. There have been exceptions, but this was to be one of the longer trips away from my family in many years.

Looking at my schedule for the month, one might wonder why I was flying to Philadelphia at all, as I didn’t have a single concert or rehearsal in the “City of Brotherly Love.” My mission there was simple, and took only about an hour. From the airport, I made my way to the home of my colleague David Yang, where my second-string cello has been living for the last few years. David was already in New York, where our trio would be working for the next week, so I picked up a key from a neighbour, let myself in and found my cello laying on the floor of his living room, grabbed it, and went back to the waiting cab and on to 30th St Station.

The “second-string cello” is a sad sign of the times. My first-string cello is pretty wonderful, and after twenty-five years together, it feels like its sound and my identity are pretty well fused. It’s also ancient and fragile. Yes, I do often buy a seat for it and travel with it, but the costs of doing so are obscene in an age when presenters are under ever more budgetary pressure. A huge chunk of what Ensemble Epomeo does is on the East Coast, and we tend to rehearse in Philly, so leaving my spare cello there has significantly lowered the threshold of financial viability for trio projects, and it does save me a lot of stress.

After a short and pleasant train ride and a shockingly expensive cab, I finally made it to Brooklyn, where I would be spending most of the next week. Our main project was to be a concert on the Kyo-Shin-An Arts series at the Tenri Cultural Center. The series is run by shakuhachi virtuoso James Schlefer and his wife Meg. James is an incredible musician and a dear friend, Meg is one of the most likable and dynamic people in the industry. We met when performing his Shakuhachi Concerto in Texas about seven years ago, and later recorded the piece with Orchestra of the Swan (it was a 2012 MusicWeb Record of the Year, I might add). Kyo-Shin-An is all about commissioning new works for traditional Japanese instruments and Western ensembles, and they’ve had works from some major figures, including Daron Hagen, Paul Moravec, Victoria Bond and James Matheson. This week, Ensemble Epomeo are performing a new work for shakuhachi and string trio by Matthew Harris, a composer completely new to me, and one by Jay Reise, a wonderful composer we’ve worked a lot with the last few years (and who’s touching work “The Warrior Violinist” was one of the highlights of our Auricolae CD).

Matthew’s piece is a sequence of very short, somewhat enigmatic movements, which on first encounter seem to have a strong Webern influence. It turns out that he was a student of Elliott Carter, but has gained worldwide fame as a choral composer of quite lushly tonal music, so perhaps this piece represents something of a stylistic homecoming? Interestingly, however, alongside all the Webern-esque concision and rigor, there seems to be the ghost of George Gershwin lurking in the background.

We’ve all put the work in on our own parts, but when we meet on Monday, it’s the first time we will have played this piece together. At this stage of the process, there is always an element of guess work- we don’t yet know Matthew or how he wants the piece played. In the end, we decide to start with the Webern thing- seeking austere, cool, smooth textures, and using extreme care with handling of silences, thinking gesturally. It may be the wrong approach, but at least it’s an approach.

(Jay’s “Warrior Violinist”. Have your hankie handy- it’s a tear jerker!)

Jay’s language, on the other hand, is pretty familiar to us by now. In addition to recording “The Warrior Violinist” (which we’ve since performed many times), we’ve played his String Trio and his Piano Quartet and worked with him in some detail on all three works. Jay’s stylistic range is pretty broad, but the new work, “The Gift to Urashima Taro,” actually seems to be very much cut from the same cloth as “The Warrior Violinist- it’s intensely lyrical and full of yearning and longing.

This will be the work’s second performance. James and David (our violist) played it together at the Newburyport Chamber Music Festival (where David is Artistic Director). The work was written as a ballet, and in Newburyport, they staged it with a wonderful local dance company and fantastic production values. As often with ballets (the same question comes up with pieces ranging from Appalachian Spring to The Firebird) there is some concern about how to handle the music that is really clearly choreographic or plot driven in nature. It’s why we know most ballet music from suites. “Urashima” is through-composed, and not that long (just over 20 minutes), and nobody is suggesting cutting anything, but in the rehearsals there are quite a few times we find ourselves saying “given that there’s no dance steps to fit in here, perhaps it would be more musically effective if we didn’t take the metronome marking too literally- it seems more like a dance marking than a music marking.” The overall tone of the work is tender and often subdued, but we did find a few places where melodies could be more extrovert without disturbing the character. In such a subtle work, it’s important to keep a strong connection with the listener.

There’s more on the program, of course, David and James will be playing a duo for shakuhachi and viola (a very cool piece). We’re doing one traditional string trio, too- Leo Weiner’s very Romantic trio written in 1908. It poses a few problems for us this week- it clearly stands apart from the rest of the repertoire we’re playing. Where do we put it on the concert? It was originally suggested to end the concert with it. The finale is certainly a barn-burner, but I thought putting the Romantic work at the end would somehow negate or diminish the other pieces we’re playing, as if we were rewarding the audience for enduring all the new pieces with something rather Tchaikovsky-an. Better to start with it. It’s a fairly new piece for us- we just added it to our repertoire this season and it was the “big” piece on our last tour in February. In spite of a lot of really intense work on it, and a few good moments in the concerts, I don’t think any of us were happy with those performances- it just never gelled. These kinds of setbacks are normal for chamber groups, but they need to be handled carefully. Even the most experienced musicians (maybe “especially” the most experienced musicians) live or die by their own confidence in what they’re doing. Even though we all knew we weren’t happy, we’ve not discussed it as a group. Starting a new rehearsal sequence with a post-mortem isn’t going to help anyone to find their mojo.

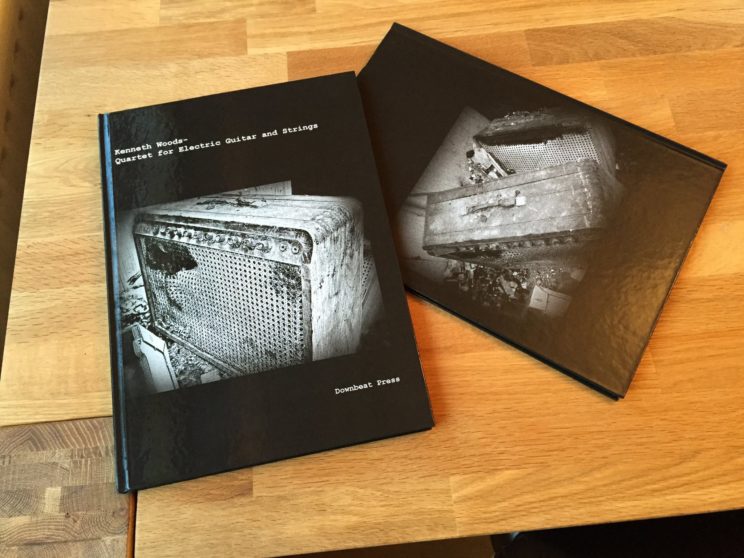

Finally, there’s my piece. This is not something that happens to me very often. As I’ve written about before, I composed quite a lot when I was young- mostly for piano, but hit a wall in my 20’s. A few years ago, with much effort, the wall finally crumbled. This week we’re playing my Quartet for Electric Guitar and String Trio. As with Jay’s piece, the work had been played once before at the Newburyport Festival, who commissioned it for their 10th Anniversary concert. I came away from that performance thinking there was quite a bit in the piece that needed re-thinking, and it sat on my shelf for nearly two years as I struggled to find time to re-examine and revise. With this project, I finally had a deadline, and rather reluctantly got to work on it. It was probably good I waited. Hearing your music played for the first time (especially when you’re playing the cello part) can turn even the most seasoned of composers into a neurotic basket case. With sufficient emotional distance from the premiere, I could look at the piece dispassionately and decided major surgery was not required. There was, of course, a lot I could do clarify my expressive wishes- accents, bowings, dynamics and a few character marks were added. Mistakes (most, but not all!) were corrected. However, structurally, I mostly left it alone, other than shortening a few rests. Of course, there are examples of great composers needing several tries to get the form of a piece “right.” Sibelius’ 5th Symphony is a perfect example- it went through several revisions over a decade before it finally found its perfect form. More often than not, however, you’re never more aware of the mix of motivic and structural issues in your piece than when you’re writing it. Chances are, when you finished it the first time, you knew it was finished because you’d reached a point at which the structure and content seemed to come into balance. Even if there are things about the piece you don’t love, it’s hard, and potentially destructive, to mess with that fragile equilibrium.

As our week in New York continued, our work on each piece of the programme took on its own dynamic. Matthew Harris was to join us for most of our rehearsals on his piece. Matthew proved to be immensely likeable, and like so many composers, he was incredibly sure of what he wanted much of the time, and full of questions at other times. He definitely felt our austere/modernist take on the piece was too severe. Vibrato was turned up, phrasing made more lyrical, some of the rests and silences were adjusted or shortened. Mutes were added in a few places. Unusually, we spent a lot of time, right up to the day of the concert, discussing the ending of the piece. Matthew, James and David all had ideas about what, if anything, to repeat, and exactly how to end. And, as always, it seems, there were some discussions about harmonics- everyone composer’s favorite special effect, but one that often frustrates the musicians. In any case, after working with Matthew, our interpretation of the piece had definitely taken on a more human quality, although when one spends hours micro-studying tiny details in a ten minute piece, it’s easy to get brain lock.

If having Matthew present proved to be an invaluable aid to understanding his language, we were very lucky to already know Jay’s music as he had to miss all of our rehearsals that week due to eye surgery (which went well). Jay had revised the piece after the Newburyport premiere (I’m glad it isn’t just me who has to do these things), and the new version showed up fairly close to our first rehearsals. I managed to re-print and remark my part before leaving home. David and James had a lot of work invested in their parts from last time, so chose to try to mark changes in the old parts rather than starting fresh. On the one hand, this kind of situation can be frustrating when one encounters changes that have been overlooked during one’s personal preparation, but it also helps to understand the composer’s thinking. Where work on Matthew’s piece was dominated by his presence, working on Jay’s piece felt like a happy maturation of the collaboration between James and Epomeo. We’ve done enough together now that working with James feels more like playing in a quartet than like having a guest join the trio.

If the sheer logistics of getting a cello to New York were at the forefront of my mind at the beginning of the week, that was nothing compared with the logistics of rehearsing my Electric Guitar Quartet. The first challenge: the building where were rehearsing everything else during the week does not allow electronic instruments of any kind, no matter how softly played. This meant schlepping over to Manhattan to rehearse at the (NY-sized, i.e. very cozy) apartment of our guitarist, Daniel Lippel (who also played the first performance in Newburyport). Such a change of scene is time consuming and rather tiring, so we decided to split our rehearsals between string sectionals without Dan in Brooklyn and full rehearsals with him in Manhattan. The other performance of the piece was just before Diane Pascal joined Epomeo, so it’s her first time playing it. Diane, who lives in Vienna, has about the most impeccable Austro-German/Central European musical pedigree of any American musician I know, but she’s also quite a rocker, and she couldn’t be more in her element in this piece, which switches between the odd hat tip to late Beethoven and bi-tonal heavy metal thrashing. I feel almost embarrassed to have such incredible musicians playing my work.

There’s one more, admittedly absurd, challenge in my piece. While writing it, I found myself thinking that what the work really needed was some Iron Maiden-esque duelling lead guitars. I figured I could switch from cello to electric guitar for this passage, which climaxes in a sequence of traded improvised guitar solos. In order to make this work, I had to overcome a few obstacles. First- I haven’t played guitar in public with any regularity since the early 1990’s, and Dan is one of the best guitarists in the world. In order for any sort of two-guitar shtick to be credible, I’d need to work really hard to get in shape and be careful to play within my current abilities. Of course, my guitars are all in Wales, and my beloved amp was scored in a fire in Pendleton in 2007, which meant borrowing a guitar and amp. In Newburyport, I’d used a beautiful sunburst Les Paul belonging to a friend of the festival. I hope I managed to clean all of the “envy drool” off it before I gave it back. This time, I borrowed a guitar and amp from Dan, who, in addition to being an amazing musician is one of the nicest guys in the business. For the first rehearsal, I borrowed his custom made instrument with an unusual neck- it was built to mimic a classical guitar’s feel, so the neck was thick and wide with big frets and fairly high strings. We were a little worried that I’d struggle (even more!) with the metal-ish writing on such an instrument, but it was okay. For the second rehearsal and the concert, I borrowed Dan’s tobacco sunburst Strat, which was doubly appropriate as it looked just like my guitar at home which I wrote the piece on. By the way, writing for guitar is an interesting challenge, and one most composers smartly avoid. One really needs a very intimate knowledge of the instrument to be sure that what you write is playable. When I was a student at IU, I wrote a song cycle for soprano and electric guitar, so this was actually my second time writing classical music for it.

Getting back and forth between Brooklyn and Manhattan while carrying a cello is really no fun at all. Doing so with a cello, amp and guitar is actually impossible, unless you take a cab. That meant however much I wanted to be in shape on the guitar, I wouldn’t be able to use the electric between rehearsals. Fortunately, James Schlefer had an acoustic at his place, so I could review my part daily on that. Far better to practice on an acoustic and perform on an electric than the other way round. At the climax of the piece, after all the guitar solos, there’s a wild, very fast, unison passage for all four of us. I was determined to get that right, and must have driven the neighbors mad (even unamplified), playing that sequence over and over again.

And what of the Weiner Trio? Well, in a week chock-a-block with composers, guest colleagues and extra instruments, doing a string trio felt like a moment of calm, which is just what we needed after last time. In fact, we rehearsed it very little during the week. I think this was clearly the right call- whatever our frustrations with last time, it was not down to lack of hard work on the piece. We beat that musical horse long after he was dead. This time, we ran it, discussed a few small tempo changes, then ran it again. It was enough.

As we neared the end of the week, we did a house concert in a very special venue we’ve played at many times. Not all house concerts are created equal. At home in Penarth, Suzanne and I have a music room in which we have concerts- it’s got a decent acoustic and feels like a performing space, which is good for everyone’s confidence. This is not that kind of house concert- here we play in a carpeted living room. The audience is only inches away and there is no acoustic at all. If you can make something sound good there, you’ll sound amazing anywhere else, but it can be bruising to the old ego. On the other hand, the vibe there is really special- one can hardly imagine a more engaged and knowledgeable audience. The concert went well, and we feel somehow less frustrated by the acoustic than usual.

That was Friday night. Our “main” concert is on Sunday (Mother’s Day- why, oh why did we schedule something on Mother’s Day!?!?!). The original plan for Saturday was to rehearse my piece for 3 hours- it had the least rehearsal during the week because of the logistical issues, and we hadn’t originally planned on playing it on Friday, although in the end, we did. As Saturday morning got going, the texts started going round- “do you mind if,” “how would you feel if we didn’t,” “I just think we’d be better off if we got some rest.” As successful as Friday’s performance was, making sound in that room took everything we had and we were all completely drained the next day. As the composer, I felt secure in our ability to play the piece the next day, but there were a few timing and articulation things I wanted to go over. Balancing my roles as cellist and composer is not something I’m used to- in Newburyport, I had slightly regretted not having the nerve to ask for certain things, but it’s not normal (or generally acceptable) to tell your chamber music colleagues how to play. Anyway, I felt that we could cover all that in 45 minutes before the concert the next day, so I put us all out of our misery. It was a good thing for me too- after 10 months without so much as a sneeze, I’d been fighting off some kind of bug all week, and after the exertions of Friday night, I had a bad feeling it was getting worse.

Recent Comments