Where does an opera really take place?

Why, on the stage, I hear you say.

Of course, that’s true, but not quite the truth. Der Rosenkavalier and The Magic Flute might take place on the same stage in the same week, but they clearly don’t take place in the same place.

Of course, in the theatre, each opera will have its own set. Some are more realistic, some are more abstract. But yes, when the situation is normal, one would hope that each opera, perhaps even each act or scene, would take place on a set that is appropriate to the action of the story.

But then what of recordings? And concert performances? Where does the action of an opera take place then?

I have long thought that one of Wagner’s greatest dramatic insights was to create the conditions by which the opera takes place in the orchestra. The characters sing in the world of the orchestra, the plot unfolds according the musical threads heard in the orchestra. The orchestra tells us what we’re looking at and where we are. The meaning, the symbolism, the emotion- it’s almost all in the orchestra. For all of his obsessions with Gesamkunstwerke (total artwork), which led him to have built the ideal opera house for his works (and to limit Parsifal to performances in that space in his lifetime, a ban which lasted until 1903), Wagner’s opera’s work better than almost anyone else’s as concert works. They work supremely well as works for recording. Solti’s Ring Cycle has stood the test of time as one of the great achievements in the history of recoded music across all genres in spite of the fact that there are no sets. You don’t need sets for Wagner. Wagner’s Valhalla, Rhine and Cornwall all exist completely, if not exclusively, in the orchestra. The world Wagner creates in the orchestra, and the stories he tells through the orchestra, are so rich, so complete, so convincing and so detailed, that as long as there have been Wagner operas there have been operatic paraphrases and orchestral suites assembled by conductors and composers which even go so far as to dispense with singers.

A certain amount of scene painting and local colour has always been part of opera. Think of the Janissary music from The Abduction from the Seraglio where a few cymbals and a bit of triangle help to give the opera a Turkish flavour- appropriate for the story and popular with Viennese audiences of the day. An obvious and often-cited influence of Wagner is Weber’s Der Freischütz, notably the wild Wolf’s Glen scene, which is certainly full of wild, evocative nocturnal portent. To me, however, in his mature works, Wagner is the first composer to really create a completely compelling and immersive world within the orchestra that seems to be able to serve as both narrative and setting from beginning to end, not just accompaniment and commentary.

Debussy worked hard to distance himself from Wagner, but was hugely influenced by the bad boy of Bayreuth. Pelleas et Melisande is one of the few works I can think of which is as immersive as Wagner. Bartok’s Bluebeard’s Castle is another.

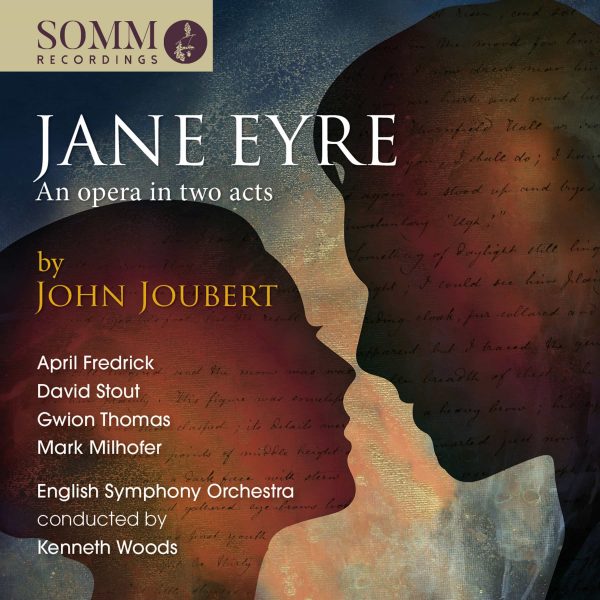

I’d spent many months working on John Joubert’s Jane Eyre before the ESO’s recent premiere and recording of it for Somm Recordings last year. I knew where there were likely to be balance problems, I knew where there were likely to be tears. What I didn’t know was just how enveloping the orchestral soundworld of Joubert’s Jane would be.

Being on a theatrical or operatic set is almost always a bit of a let down- however convincing a production is at making you think you’re watching the real thing in the audience, when you’re on stage, it looks like you’re in a theatre. Everyone around you is wearing freakish amounts of makeup. The sets look cheap and fake, you can see into the wings, and when you stare pensively into the distance, there are hundreds of punters staring back at you. Being in the middle of the action on stage you have to work harder to suspend disbelief than the audience.

In Wagner, however, I think that when you’re surrounded by that music, it’s even more immersive for the musicians than for the listeners. And so it was, to my surprise and delight, in Jane Eyre.

From the first notes of the first scene in the first rehearsal (for once, we actually managed to start with the first bar of Act 1 –Scene 1), it really did feel like we were entering a world of John’s imagining. Over the course of those two short but epic days, my mind built sets. Colors of walls were noted, shifting shades of light coming through windows were observed. I came to picture the rooms of Thornfield during Jane and Rochester’s courtship, I came to feel a slightly ominous sense of dread as the church doors opened to reveal their doomed wedding ceremony, and I can still feel the smug claustrophobia of St John Rivers’ house during his confrontation with Jane.

That this vivid, rich and compelling world existed only in John’s imagination and in the printed instructions he put on the page for nearly 20 years is both depressing and inspiring. We as musicians sometimes take for granted the miracle by which a score can preserve a piece of music in static silence for decades until it can be heard. But it is even more miraculous when finally hearing that music can allow a drama to be seen, allow characters to come to life, allow buildings and landscapes to be observed and remembered. The acrid smoke of Bertha’s fires sting the nose through the orchestra. When Rochester sings of the nightingale, one sees the night, feels the evening dew settling in, all through the orchestra.The world of Joubert’s Jane Eyre certainly cast a spell on me- I can scarcely think of an opera which begins and ends more magically, and throughout our work on the piece, I feel like I spent hardly a minute in Edgbaston.

Those were two very happy days, and I very much hope that we’ll be able to reunite that astonishing cast for another round of performances, but for now, the world of Jane Eyre is one I can remember but not visit. It was lovely to see David and April, our magnificent Rochester and Jane, at John’s 90th birthday the other day. Some things are too fragile and too precious to discuss, but seeing them, in a noisy function room full of cake and tea and saturated with oppressive fluorescent light, I felt myself, just for a very, very brief moment, remembering what it was like to stand in the ruins of Joubert’s Thornfield watching two damaged lovers heal each other and re-start their lives. I hope that we did a good job of allowing our audience, both live and through the recording, to “see” the action unfold through John’s miraculous scoring, but we are the blessed few who have not just seen Joubert’s Thornfield, we have been there. Such things are not for discussing at social occasions. Such things are not for discussing at all.

Those of us who have been to Joubert’s Thornfield are both blessed and changed, forever just a little homesick for a world created by a great composer and finally brought to life for 48 precious hours by 35 hard-working musicians. Getting there costs more than most journeys, but at long last a few of us know the way.

Recent Comments