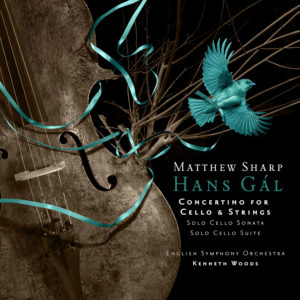

Hans Gal (1890-1987)

Concertino for Cello and Strings, opus 87

Hans Gál was born in the small village of Brunn am Gebirge, just outside Vienna. He studied with some of the foremost teachers in Vienna, including Richard Robert for piano (teacher of Rudolf Serkin , Clara Haskil and George Szell) and Eusebius Mandyczewski for composition, who had been a close friend of Brahms. In 1915 he won the K. und K. (Royal and Imperial) State Prize for composition for a symphony (which he subsequently discarded). In 1928 His Sinfonietta (which was to become his ‘First Symphony) won the Columbia Schubert Centenary Prize. The next year, with the support of such important musicians as Wilhelm Furtwängler, Richard Strauss and others, he obtained the directorship of the Mainz Conservatory. Gál composed in nearly every genre and his operas, which include Der Artz der Sobeide, Die Heilige Ente and Das Lied der Nacht, were particularly popular during the 1920s. When Hitler rose to power, Gál was forced to leave Germany and eventually emigrated to Britain, teaching at the Edinburgh University for many years.

Gál’s music enjoyed a brief resurgence in popularity in the years immediately after World War II, and was featured regularly in broadcasts on BBC radio. However, by the 1960s, BBC director William Glock’s programming philosophy, sharply slanted in favour of strictly modernist music, meant that Gál and other tonal composers of the time found themselves unable to get their music on the airwaves of the “Third Programme.” Gradually, performances also became more and more scarce, and Gál was deeply affected by the death in 1964 of his friend and foremost champion, conductor Otto Schmitgen. There were personal tragedies as well- Gál’s younger son Franz died by his own hand during this period. Circumstances for new work in a tonal idiom were similarly bleak on the continent, and commissions for new works in standard genres or for traditional instruments were almost non-existent. Indeed, the main champions and patrons of Gál’s music at this time were recorder player Carl Dolmetsch and Vinzenz Hladky, Professor of Mandolin at the Vienna academy of Music and publisher of mandolin music, who had instigated Gáls’s writing for mandolin in the period back in Vienna between 1933 and the Anschluss in 1938. Now in the 60s, Hladky published and regularly performed Gál’s music with his mandolin ensembles, to which Gál responded with two Sinfoniettas for Mandolin Orchestra, amongst other works. The Concertino for Cello and Strings, the last of Gál’s five concertinos, was written in 1965, inspired purely by Gál’s inner impulse, rather than a commission. It was premiered in 1968 by the Sudwest Rundfunk Orchestra.

What exactly does Gál mean by a “Concertino” rather than a “Concerto”? For some composers, the word “concertino” implies a certain frivolity or lightness of tone, while for others, it implies a work of very modest scale. Neither is true for Gál- the sole unifying factor of his five concertini is that they are all scored for solo instrument and strings, rather than full orchestra. Certainly, there is nothing frivolous about the Cello Concertino, and it is substantial work by any measure- at 27 minutes, it is roughly the same length as his Violin Concerto from 1933. There, however, is plenty of quirky humour in the Finale, which bears the curious tempo marking of “Allegretto ritenuto assai” or “slightly fast, but very held back.” The first movement, which is far more serious in tone, is built from the six note cell which opens the entire piece. Typical of Gál is the persistent ambiguity of major and minor which makes for an atmosphere both questioning and uncertain. At the work’s heart is a touching and lyrical Adagio, absolutely echt-Gál in its bittersweet tenderness. Had he so wished, Gál could certainly have made a killing in the lullaby-writing business.

Kenneth Woods

Recent Comments