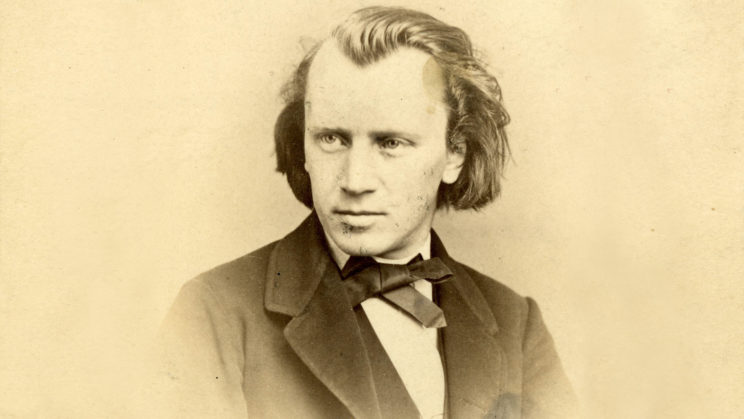

A little update on the Brahms Piano Quartet orchestration project, for those of you interested….

A little update on the Brahms Piano Quartet orchestration project, for those of you interested….

A quick summary of how we got to where we are!

The arrangement had its genesis in 2008 in Ischia when the idea came to me. I spent a good chunk of that summer annotating my score of the original version. In spite of my great excitement for the project, that was the year my first child was born and the project kept getting pushed back and pushed back. In autumn 2014, I’d hoped to programme it with my friends in the Surrey Mozart Players, but again, it had to be pushed back (my fault) until the end of that season. Finally, in June 2015, we did it. 2014-5 was a monumentally intense year here on all fronts, and the orchestra were unbelievably helpful, patient and supportive through the whole process. A particular challenge when adapting a piece with a significant piano part for orchestra is how closely do you adhere to the original- where is the line between making it absolutely faithful to the original (not actually possible) or idiomatic (not always Brahms’ own primary concern, but an important one)? It was a memorable and exciting experience. I felt like the piece worked very well in its new orchestral clothing.

After the elation and relief of the applause, I already knew revisions were called for. Mindful of Brahms’ well-documented sense of restraint and affection for the traditional roles of the instruments, I had handled the brass in particular with a great deal of discretion. After the performance, I realised I had erred too much on the side of caution, and, looking again at the full range of Brahms’ orchestral music, there was more scope for using the brass creatively and expressively than I had allowed for. I spent some of the rest of the summer revising the score.

Fast forward to 2017. At last- a performance is secured with the English Symphony Orchestra. Time now for a final revision. Time clarifies things. In a process like this, it’s useful to capture the moments of inspiration and insight, such as the early days on Ischia or the days immediately following the SMP performance, and to try to get one’s thoughts on the page as fast as possible. On the other hand, closing the score for 18 months and coming back to it with fresh eyes is equally important, and going through it slowly again this summer has helped me to see further opportunities for improvement and to find previously elusive solutions for some technical challenges.

Who knew it could be so complicated? I’ve always rated Brahms as an absolute genius of orchestration, and to orchestrate his music, you have to understand the rhetoric of it. I thought the first version was pretty successful on the rhetorical front, but needed more pizzaz.. It’s not just about assigning notes to parts in an attractive way, but that is important. Getting close to his fluency and honesty as an orchestrator has proved a monumental challenge, especially when dealing with the piano writing. I was slightly cheered earlier this summer to hear David Matthews speak about some of the orchestrational challenges of Mahler’s 10th Symphony that he and the Cooke team spent years discussing. For whatever reason, finding the right orchestration for a master’s music seems to be inevitably harder than finding it for your own. I think (hope!) we’re just about there with this piece, and finding a way to solve problems which have stymied you for years can be sooooo satisfying.

The first part of this story in a way was about struggling to find time for a project. Thankfully, once we got into the work of that first performance in Guildford, the project asserted itself and it finally started to get the time it needed. There’s nothing like a few weeks of all-nighters to move a project forward. Hearing it and working on it with a live orchestra was invaluable. Now, taking time over the final corrections is proving equally valuable.

Remember, we’re tying the professional premiere of the piece in Cheltenham Town Hall on the 21st of November to a recording for Nimbus Records, but we need your help to make it happen.

Free CD for all donations over £40

Free download for all donations.

Ken— Interesting thoughts. You’re right, though, it must be far more difficult to be “true” to someone else’s ideas when undertaking a project like this. I personally don’t think Mahler worried too much about making his Death and the Maiden orchestration sound all that Schubertian. But the many who have tried to complete M-10 from sketches– very daunting.

I’ve always admired the obvious choices for orchestration– Rimsky, Ravel, Respighi, even Puccini, and Korngold. Somehow I’ve always taken Brahms orchestrations for granted. I mean HOW ELSE could they sound?? Thanks for sharing your thoughts.