Thurs April 19th at 730 PM

St John’s Smith Square

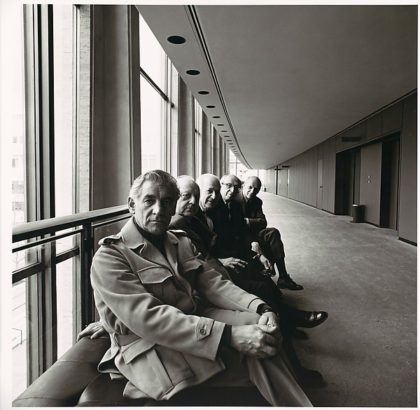

Leonard Bernstein, Virgil Thomson, Walter Piston, Aaron Copland, William Schuman

No smart musician turns down much work, but when I first came to the UK to build a new musical life, I did my best to steer clear of doing lots of American music. I thought that if I spent my first few years in the country conducting Bernstein and Gershwin’s greatest hits, that would probably be the only repertoire I would ever get to conduct here. It also concerns me that only a handful of the most popular American works seem to make it to the UK with any regularity, just as in America, most orchestras dare not venture far beyond the Enigma Variations and the Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra.

One of Leonard Bernstein’s greatest legacies was his lifelong advocacy for American music, spanning a huge spectrum of generations and styles. With that in mind, when David Wordsworth approached us about the ESO participating in Americana ’18, I thought that the best way we could celebrate the Bernstein Centenary would be to follow his lead and try to bring to St John’s some of the works he championed during his life and something from the new generation which I hope he would have loved.

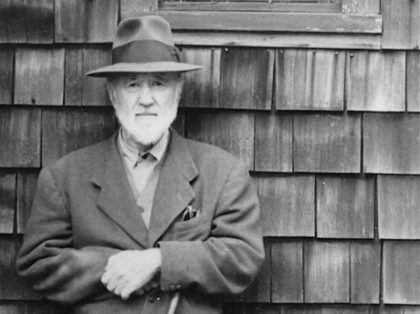

Bernstein studied music at Harvard University, where his primary music professor was Walter Piston, whose wonderful Sinfonietta closes tonight’s concert. Piston was an influential pedagogue who also taught Samuel Adler, Leroy Anderson, Arthur Berger, Elliott Carter, Irving Fine, John Harbison, Gail Kubik, Noël Lee, Robert Middleton, William P. Perry, Daniel Pinkham, Ann Ronell, Frederic Rzewski, Allen Sapp, Harold Shapero, and Claudio Spies, Robert Strassburg, and Yehudi Wyner. His books on counterpoint, orchestration and harmony are considered classics and sit on the desks of composers all over the world to this day. It is therefore a bit of sad irony that Piston’s extraordinary legacy as a writer and teacher has led many timid conductors and programmers to assume that his music is in some way “academic” or lacking in spark or temperament. Nothing could be further from the truth. His grandfather, Antonio Pistone, was from Genoa, Italy, and there is a definite Italianate intensity and passion in Piston’s music. He was one of a generation of American composers who worked throughout the middle decades of the 20th Century to see what the “Great American Symphony” might sound like, and his eight symphonies are a major contribution to the genre- perhaps the most substantial body of work of any American symphonist. His Sinfonietta, written in 1941, is a three movement work which explores some strongly contrasting moods. The first movement is full of tension and uncertainty, while the Adagio which follows it goes into even darker territories. However, in the final Allegro vivo, Piston blows the dark clouds from the skies with a movement brimming with rhythmic life and invention.

Bernstein was a key member of the generation who brought Charles Ives’ music to the attention of the world. Ives, who had combined his work as composer with a successful career in insurance, had written an astounding body of visionary works in the years between about 1890 and 1916, before largely abandoning composition after the Fourth Symphony. It was during the 1930’s that Ives music was first discovered. Aaron Copland was one of a number of composers who championed his work in those early years, and Copland wrote an influential review of Ives’ first major musical publication, the collection of 114 Songs. In 1939, the pianist John Kirkpatrick’s New York Town Hall performance of the Concord Sonata in 1939 proved to be a watershed, and gradually, people began to take up the orchestral music. Nicolas Slonimsky led a tour of the Three Places in New England and in 1946, composer Lou Harrison conducted the first performance of Ives’ Symphony no. 3, “The Camp Meeting” and the work was subsequently awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Music. Ives developed the Third Symphony from some organ pieces he had written in 1901. The Symphony was completed in 1904, although Ives revised the work several times between 1904 and 1911, and some of the versions made during this time are lost. In fact, the final fair copy he had made in 1911 was, according to Ives, given to Gustav Mahler who had seen it and expressed an interest in programming the work at the Philharmonic. Mahler, then desperately ill, took the score with him on his final voyage back to Austria, where he died on 18 May, 1911 and the score remains lost.

The three movements of the Symphony evoke the coming together of a rural community for a typical religious revival in a country tent, the sort of event that brought back many poignant memories of childhood for Ives. Most of the thematic material in the work, as so often in Ives music, comes from vernacular sources, in this case, from a number of hymns, including “What a friend we have in Jesus, “There is a fountain filled with blood”, “The Happy Land” and “Woodworth- Just as I am”. The text of that hymn underpins the cello solo which ends the symphony: “Just as I am, without one plea but that thy blood was shed for me, and that thou biddest me to come to thee, oh Lamb of God, I come, I come.”

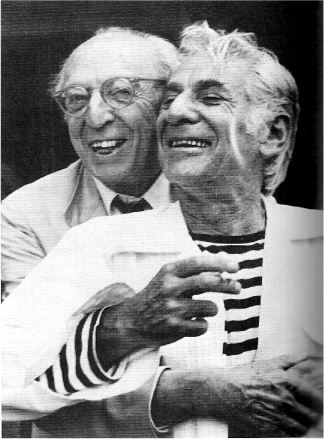

Old friends- Lenny and Aaron

The relationship between Copland and Bernstein was exceptionally close and lasted through most of the two composers’ adult lives. A friend who knew them both once said to me that the only good to have come from the dementia which blighted Copland’s last years was that he was spared the news of Lenny’s premature passing about 6 weeks before his own death. Copland’s Clarinet Concerto comes from 1948, written the peak of his fame, when Copland’s music was at its most outward looking. The Concerto was commissioned by the jazz clarinettist, Benny Goodman, and one can hear Goodman’s influence in the spiky syncopations of the second movement. It is music of ecstatic good humour, written at a dark moment in American history when Copland was keenly aware of the need to lift the spirits of the nation. The first movement is simply one of the most beautiful things ever put to paper by any composer- dreamy reverie full of longing and tenderness.

Throughout his career, particularly during his prolific years with the New York Philharmonic, Bernstein did an incredible amount to bring new and unknown music to the attention of the listening public. I am confident he would take absolute delight in the work of Jesse Jones, whose Smith Square Dances fills out tonight’s concert. This is also music of ecstatic humour- Jones takes a little bit of commonplace musical material, in this case the horn call, and goes on an absolute rampage with it.

— Kenneth Woods

Surely that’s Virgil Thomson sitting between Lenny and Piston.

And surely the location is Philharmonic/ Fisher / Geffen Hall.

Good reasons, and a fine post!

What a wonderful post, Ken. I agree with you about the Copland Clarinet Concerto. It’s a masterpiece.

A little off-topic, but it always bothered me that Copland was so dismissive of non-American nationalist composers such as Sibelius and Vaughan-Williams. Do you have any opinion on why this was?

Composers all have blind spots. I suppose we all do, but with composers, they tend to be a bit more acute and a bit more random!

LOL, well said!