I was deeply saddened today to hear of the passing of composer Paul Méfano. He died today at the age of 83.

Méfano was the founder of the well-known French contemporary music ensemble, Ensemble 2e2m. As a composer and former pupil of Messiaen, we was in the very thick of the key developments of French moderism in the 2nd half of the 20th Century.

I wanted to share my memory of Maestro Méfano, who I only worked with once.

Early on in my time in Wales, I used to work occasionally with a group called the Contemporary Music Ensemble of Wales. It was a fantastic ensemble made of members of the BBC National Orchestra of Wales as well as some stupendous new music specialists from around the UK. Although it was not a BBC group, it often recorded for the Radio 3 program Hear and Now.

Their Artistic Director was a composer named Gordon Downie who appeared to me to have a particular interest in works on, or over, the edge of playability. When programming things, he would sometimes send me a score with a note along the lines of “this piece fell apart on live TV under (insert famous conductor here), do you want to try it?”

For Gordon, discovering Paul Méfano’s Interférences was like stumbling on the Holy Grail of impossible pieces. Apparently, Michael Gielen had had something like 25 rehearsals for the premiere, at which it fell apart completely. Then Bruno Maderna tried it again on something like 40 rehearsals, and it fell apart once more. So, Gordon asked, did I want to have a go?

Well, I was new to the UK and anxious to work with musicians of this caliber, and I always loved a bit of danger, so I, of course, said yes.

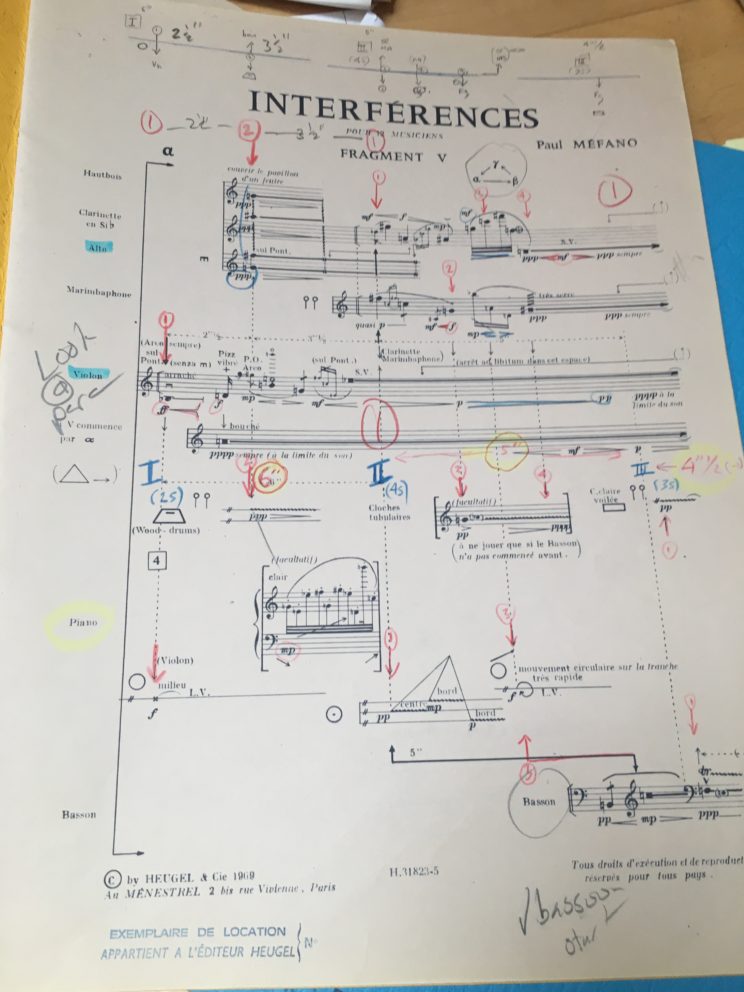

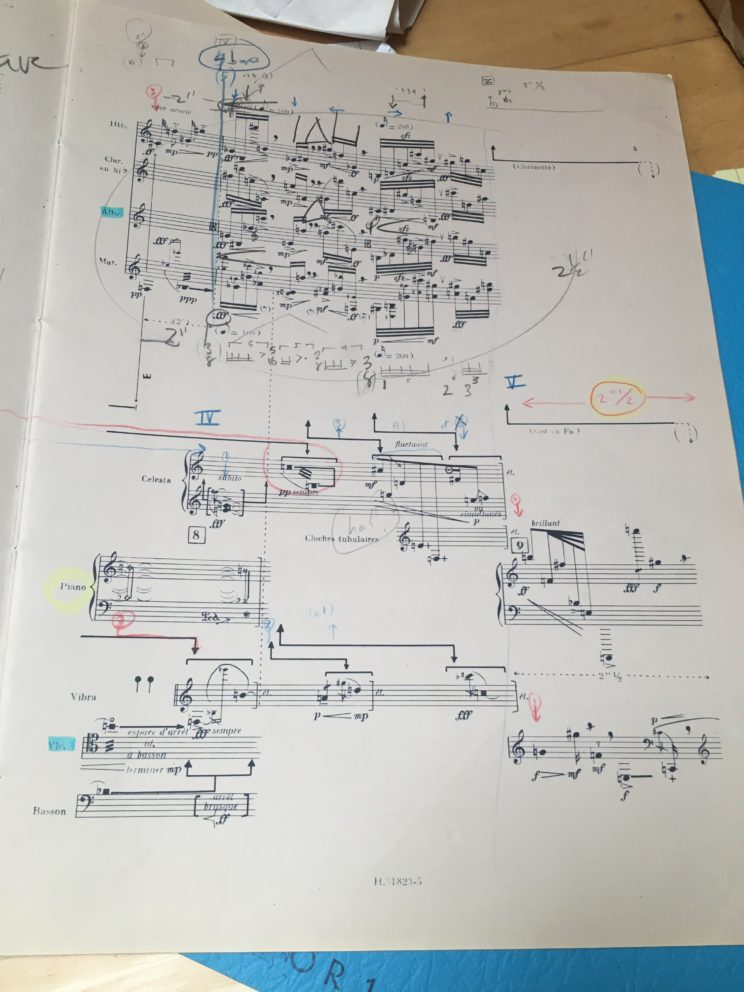

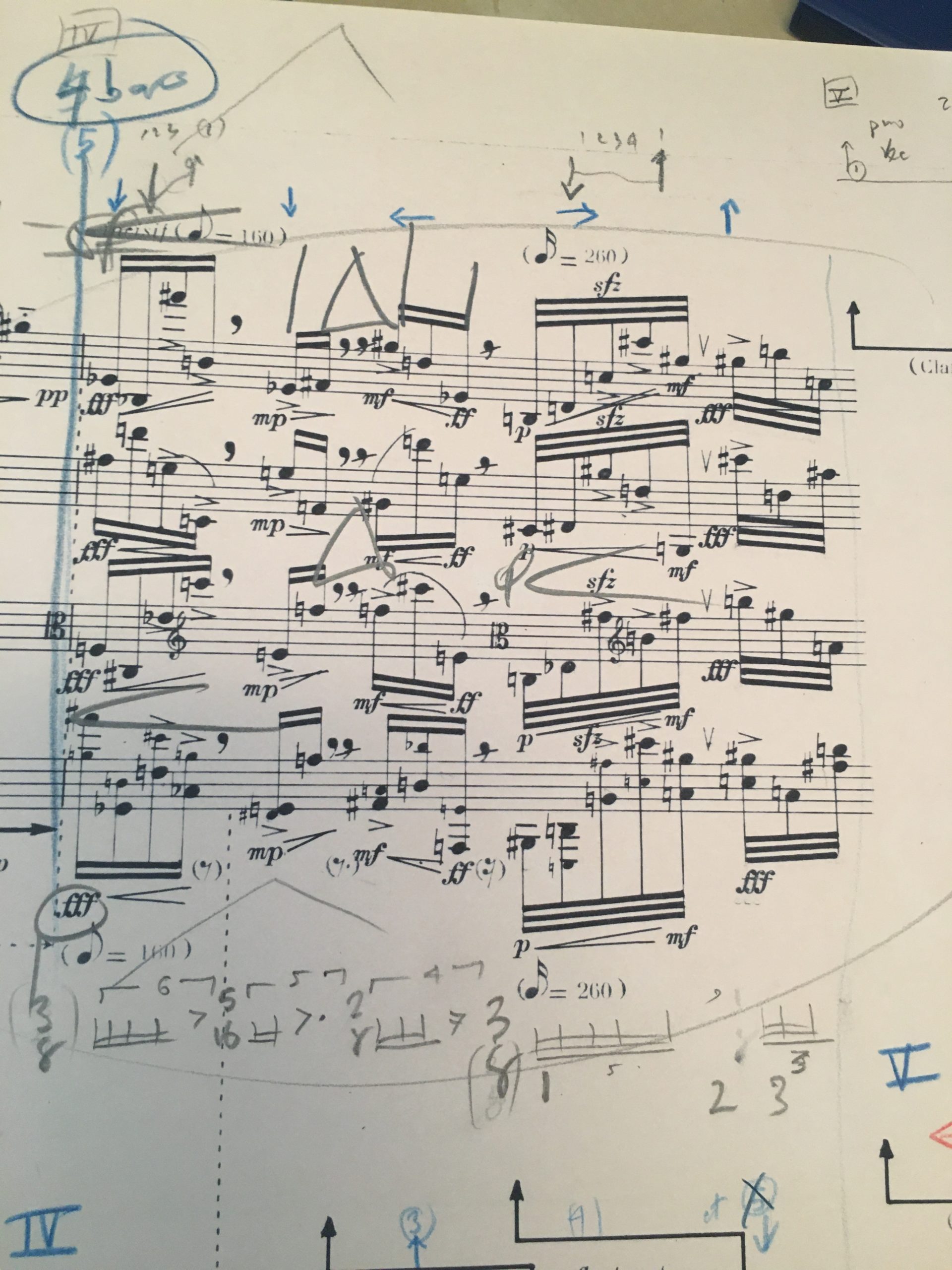

Without going into great detail, Interférences is so difficult and so dangerous because it has a perfect storm of highly complex music that needs to align very precisely (and which is quite vaguely notated in many places, with complex metrical passages which have no barlines) which sits alongside a very adventurous approach to improvisation and chance.

Mefano later explained to me that Interférences was “ultimately not realistic, but it embodied a beautiful idea, of music in which different clouds of time and activity swirled around each other freely.” What makes it dangerous is that what goes on in those freely swirling clouds is so complex and so vaguely notated.

However formidable his music’s reputation, when I finally connected with Paul on the phone to talk through the piece, I found him to be one of the kindest and most charming people imaginable. Completely without ego, he had clearly moved on from this extreme of musical experimentation, and yet he told me in an email “The project does interest me of course, I love my children, and share my ideas with talentuous musicians as you.”

Paul very kindly agreed to come to the concert, and wrote a couple of weeks ahead of time to ask “How are going the rehearsals, and Interférences?” I had to break it to him gently that the rehearsal he was coming to the day before the concert was THE rehearsal. That’s British music making for you!

In person Paul was even warmer and more engaging than on the phone, and over the course of the weekend and a couple of very good meals, I managed to get all kinds of amazing stories out of him about the giants of 20th Century music he had known, all told without a hint of name-dropping or self-importance.

Gordon, of course, seemed thrilled to be in the presence of someone who had himself actually written an “impossible” piece, but I don’t think he took it well when Mefano described Gordon’s own, incredibly complex work as “very beautiful” and “actually very Romantique.” Was that a little glint of mischief I saw in the great man’s eye?

Here, in Paul’s memory, is the recording of our performance of Interférences which, against all the odds, went quite well. There is a short interview with Mefano before the performance.

Recent Comments