What follows is an essay about my new Performing Version of Mahler’s arrangement of Schubert’s Death and the Maiden String Quartet, premiered at Colorado MahlerFest in 2024.

Franz Schubert may have had an even more powerful influence on Mahler’s creative personality than Beethoven, one which is perhaps most easily seen in Mahler’s earliest and latest works. Mahler’s first fully-formed masterpiece, Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen (Songs of a Wayfarer) is practically a musical love letter to Schubert’s late song cycles, Die schöne Müllerin and Winterreise, and this influence remains strong and almost ever-present through Mahler’s Fourth Symphony. Schubert’s influence is perhaps less keenly felt in Mahler’s middle symphonies, but again becomes central to Mahler’s final trilogy of works, Das Lied von der Erde and the Ninth and Tenth symphonies.

Schubert was only thirty-one at the time of his death, and yet the works from the last years of his life are often cited as exemplars of a ‘late style.’ The sense of leave-taking present in almost all of Schubert’s last works has much in common with that in late Mahler.

Mahler began work on an arrangement of Schubert’s penultimate String Quartet in D minor around 1896, marking up a score of the quartet with his ideas. He had envisioned making string orchestra versions of the greatest works in the string quartet literature, and had worked on versions of the Schubert and two by Beethoven: the “Serioso” Quartet opus 95, and the great Quartet in C-sharp minor, opus 131. Only the Serioso was performed in its entirety. The arrangement of opus 131 is lost, and it remains unknown just how complete it was. The sole performance of the Serioso in 1889 was interrupted by so much booing, that Mahler sent two members of the orchestra into the audience to eject the most vociferous complainers. With the exception of Eduard Hanslick, critical reaction was overwhelmingly negative. Mahler cancelled the planned performance of Beethoven’s opus 131 Quartet and never conducted the Serioso again.

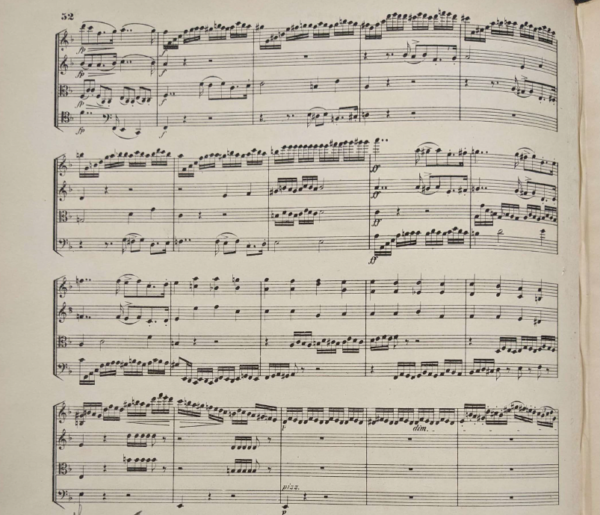

One of many pages in Mahler’s score without any annotations in his hand. This is consistent with the arrangement being left in an unfinished state.

In the case of the Schubert quartet, Mahler conducted only the second movement in a concert in Hamburg in 1896. Alma Mahler eventually bequeathed Mahler’s copy of the quartet score with his markings to Donald Mitchell, and it was Mitchell and composer David Matthews who put together the first published version of Mahler’s arrangement. Matthews and Mitchell’s work is scrupulous and meticulous.

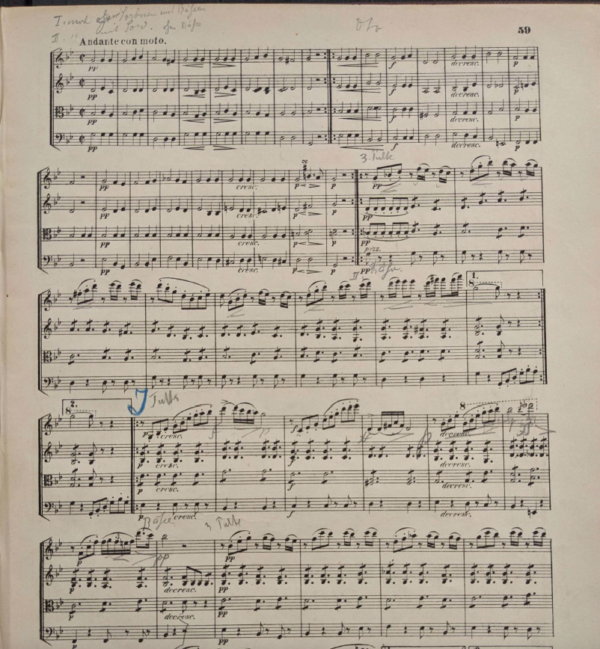

This opening page of the second movement, the only movement Mahler conducted, shows a much more detailed set of markings. It seems quite certain that the other movements would have been much more carefully and thoroughly worked through had Mahler had the opportunity to perform them.

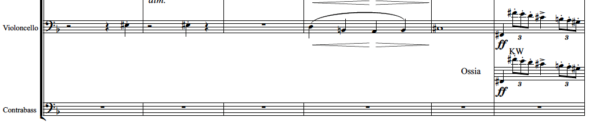

Around 2007, I was heading to a concert with my friends in the wonderful Rose City Chamber Orchestra when I found out that the publishers of the main work on our program, the chamber ensemble version of Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony, had sent the wrong piece. Someone suggested doing Death and the Maiden, but there was no chance of getting the parts to that either. Instead, I stayed up all night marking up a set of string quartet parts as best I could remember with Mahler’s changes. As I went, I allowed myself the licence of adding a few things to the double bass part. The result left me with a lot to think about: not least the fact that Mahler didn’t use the basses at all for almost the entire development and coda of the first movement.

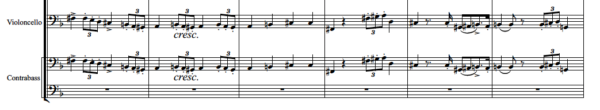

Mahler’s omission of the basses from almost the entire development section of the first movement seems very unlike him. The editor’s ossia is clearly marked, and the bass part is printed with both the ossia and the version with Mahler’s empty bars (the lower line) so the performers can make up their own minds about what to include.

More recently, I was able to obtain a scan of Mahler’s copy from the British Library. A careful inspection led me to two conclusions. First, that David Matthews had done a fantastic job in transcribing it, and second, that Mahler had definitely never finished it. In fact, the level of detail of his markings and emendations in the one movement we know he conducted is so much greater that it left me feeling a little uncomfortable calling the other three movements Mahler’s. Especially when one compares the very sketchy level of detail in Death and the Maiden to Mahler’s retouchings of the Beethoven, Schubert and Schumann symphonies.

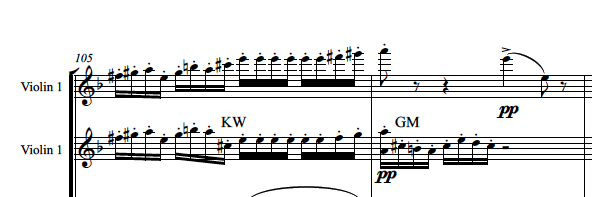

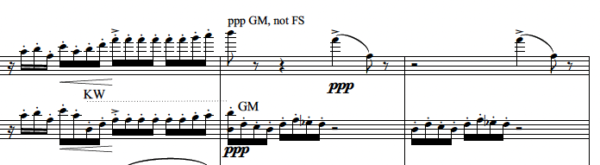

Mahler generally took care to reinforce extremely high violin writing, except when using it as a very intense effect (often in his late music). Here, I’ve suggested an octave divisi in the violins (annotated KW). In the following bar, the divisi comes from Mahler’s own score and is marked with a GM.

In the end, I donned my metaphorical protective headgear and took up the challenge of producing a ‘performing version’ of Mahler’s Death and the Maiden sketches. I’ve looked carefully at Mahler’s own string writing, his arrangement of the Serioso, and contemporaneous string orchestra arrangements of chamber works such as those by Schoenberg, and tried to bring this arrangement to a more ‘finished’ state – one which I hope gives a more accurate sense of what Mahler’s plans for the project probably were. I took courage in this from the example of Mahler’s completion of Weber’s Die Drei Pintos and the Cooke Performing Version of Mahler’s 10th Symphony (to which David Matthews made such an important contribution). One of the beauties of Cooke’s version of the Tenth is that the score includes a complete transcription of Mahler’s incomplete draft, so the interpreter can see exactly what is Mahler and what is Cooke and Co.. In my new edition, anything I have added, which amounts mostly to the filling out of the bass part and some changes in string divisi, is clearly marked and can be easily omitted.

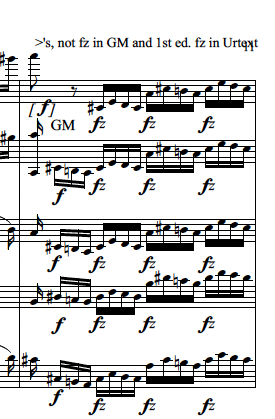

Mahler’s deliberate changes of Schubert’s dynamics and tempi are pointed out in the score, but remain included in the parts as they represent an important part of Mahler’s creative contribution to the arrangement

Schubert scholarship has also come on a great deal since Mahler’s time. Mahler’s score was a copy of the old Collected Works edition of Schubert co-edited by Brahms and Eusebius Mandyczewski. The more recent Urtext editions give a great deal of valuable insight into Schubert’s unusual use of accents and other expressive markings. Where the modern Urtext offers a clearer window into Schubert’s intentions, I’ve incorporated those into the edition, usually with some note of explanation. However, where Mahler has made a creative choice to change something by Schubert, I have left that in place. Mahler’s scores of the music of other composers offer an incredibly important and useful window into his approach to interpretation, one that is essential to understand when trying to do justice to his music.

Where modern scholarship has revealed major discrepancies between the old Breitkopf edition used by Mahler and the modern Urtext editions, these are noted.

Schubert’s use of hairpins has long bedevilled editors because of their inconsistency. The old Breitkopf edition, on which Mahler’s version was based, tended to use either a long/traditional hairpin, or to standardise markings to >’s. The Performing Version attempts to print these as they appear in Schubert’s and and the Urtext. Whether they should be read as broad accents/emphases or diminuendi is a matter for the interpreters to grapple with.

I‘m performing this with the Anchorage Chamber muss festival this week and I would very much like to get a copy of your double bass part ASAP. How could i do that? Is it for sale?