To make the reading experience more engaging, we’ve linked to audio samples of the various musical examples discussed. Look for the highlighted text. Chances are, in most browsers a little box will pop up over the text where you can play the excerpt without leaving the page. If not, just click on it and something good should happen.

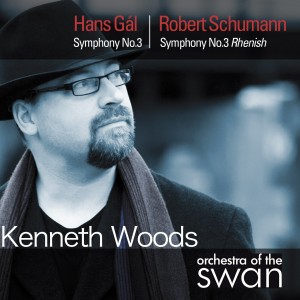

Robert Schumann: Symphony no 3 in E flat Major, opus 97

Schumann’s Symphony in E flat Major was his final work in the genre which had occupied so much of his energy over the previous ten years of his career. Written around the time of his arrival as the new conductor in Düsseldorf, it is a vibrant testimony to what was to be the last truly happy time in his life. The work has always been among Schumann’s most popular, but has often been misunderstood- Schumann himself never called it the “Rhenish,” and the often-cited story about the symphony’s fourth movement being inspired by Schumann’s viewing of the investiture of a new cardinal at Cologne Cathedral is just that- a story. Schumann’s family diary clearly records that the Schumann’s were at home in Düsseldorf that day. There’s absolutely no evidence anywhere in Schumann’s own correspondence that this movement was inspired by the Cologne Cathedral, or any other building for that matter.

Schumann composed the Symphony in E Flat over about 6 weeks in 1850- an eternity compared to the four days in which he wrote the “Spring” Symphony in 1841, but a blink of an eye compared to the 17 years his disciple Brahms, intimidated by the example of Beethoven, spent on his First Symphony.

Where Brahms hesitated, Schumann rushed in. There is surely a sense of playful provocation at work in this symphony- Schumann would have realized that any symphony in E flat major, especially one that began with a movement in brisk ¾ time, would be sure to be compared Beethoven’s Eroica, and to its model, Mozart’s Symphony no. 39. If Brahms’ C minor symphony (his first) is his answer Beethoven’s (the 5th), Schumann’s answer to Beethoven 3 offers a telling comparison. Brahms’ work, although epic, is in many respects more conservative and classical than Beethoven’s. Gone in Brahms are innovations like the elision between the 3rd and 4th mvts in Beethoven 5, or the stunning return of the Scherzo at the crisis point of the finale of the same work.

Schumann, however, seems determined to show he can meet Beethoven on his own terms while taking the medium forward: where Brahms seeks to restore classical order, Schumann charges forward in the spirit of innovation. Well aware of Beethoven’s profound sense of motivic rigor, Schumann built his E-flat Symphony around the intervals heard in the first two bars of the theme- falling 4th, rising 6th and rising 4th. The perfect fourth, in particular, becomes the central unifying element of the bulk of the symphony. Schumann also seems determined in the opening Lebhaft (Lively) to show that he can generate the same kind of overpowering sense of momentum and direction first found in the Eroica, yet he does it in a movement of about half the duration of the Beethoven.

Beethoven- Brahms was a little scared of him, but Schumann was not. Schumann probably never saw this picture…

There were other symphonies with five movements before Schumann 3, but in many important ways, the Rhenish (a nickname which originated with Schumann’s publisher and not the composer, who asked him to remove all programmatic references from the score) is the real first five-movement symphony- Beethoven’s Pastoral and Berlioz’s Fantastique are both basically four movement symphonies with an “extra” movement added for narrative purposes. They could have been 6 or 10 movements long if the narrative demanded it. Conversely, in this piece, Schumann finds fascinating possibilities of creating a new sophisticated, symmetrical three part form. The Rhenish is essentially a triptych in which the first two and final two movements form connected pairs through thematic cross references and shared ideas. Like the Lebhaft, the Scherzo which follows it is in ¾ and full of themes built around the interval of the perfect fourth. Schumann’s invention in this piece was to prove a decisive influence on Gustav Mahler, who appropriated the scheme almost exactly in his 5th Symphony, and built on it in his 7th and 10th. Schumann’s Scherzo starts innocently and seems to promise a bit of light relief after the heroic 1st movement, but after the wonderfully sophisticated Trio, it proves itself able to generate just as much power as the Lebhaft, offering a dramatic culmination of the first part of Schumann’s symphonic triptych. However, the passionate climax of the movement quickly dissipates, and the first panel of Schumann’s triptych ends on a surprisingly enigmatic and understated note.

The 3rd movement is a charming intermezzo- after two such powerful statements, Schumann takes us to a world he understood perhaps better than any composer- a universe in miniature where innocence, elegance and understatement meet fantasy and profundity. Tellingly, it is the only movement in the Symphony in which perfect fourth plays no significant role in the construction of themes. There is one important exception: just before the end of the movement, the solo horn plays the first conspicuous melodic fourth: B flat to E-flat, an inversion of the first two notes of the symphony, and an ominous foreshadowing of the movement to come. It is perhaps Schumann’s sober reminder that no dream, however blissful, lasts forever.

The final panel of Schumann’s triptych begins with one of the greatest and most original slow movements in any symphony, marked “Feierlich” (Solemnly), in any symphony. Schumann’s choice of key is telling- E flat minor was a special key for the composer. Notably, he used the same key to evoke Manfred’s existential and suicidal despair in his setting of Byron’s poem written the year before. For Schumann, this key was a conduit into the abyss of his own nightmares. Written in austere contrapuntal style, and unremitting in its severity, it is built entirely from the opening theme in the trombone and horn- a series of rising fourths (alternating perfect and diminished 4ths), beginning with an inversion of the Symphony’s first two notes, B flat and E flat. Any listener still confused by lesser composers’ self-serving criticisms of Schumann’s genius as an orchestrator should look first to this astounding movement, in which almost every bar has some touch of colouristic genius.

The Finale, again marked Lebhaft, is like a mirror image of the Feierlich. The main theme again expresses the rising fourth from B-flat to E-flat, but this time as an ascending scale, followed by a falling fourth, as in the opening of the symphony. Undetectable to the listener at first, Schumann is drawing together the threads of the entire work from the first bar. Again and again, Schumann brings back ideas from the Feierlich, however, completely without solemnity or anguish. What was once unbearably dark is now presented in the spirit of carefree good humour- Mahler would mimic this technique of transformed thematic cross references almost exactly when using the themes of the Adagietto in the Finale of his 5th Symphony. (Note also that the four note motive that opens this movement is almost exactly the same as the main four note theme of the Mahler). At the climax of the symphony, the brass re-state the opening of the 4th movement, but now in major and in fully triumphant mood, fast and fortissimo, and the symphony concludes in a blaze of optimistic affirmation.

Gus Mahler was paying attention in Schumann class

Programme notes copyright Kenneth Woods, 2010. Not to be reprinted or reproduced without permission of the author.

Audio material and images under other copyright is reproduced here without profit under Fair Use provisions of relevant copyright law for educational purposes only. All privileges remain the sole domain of the copyright owners

I like your comments about the fourth movement (Feierlich) of the Schumann Rhenish Symphony. I teach a piano laboratory/ music technology class here in Brookville, Indiana. I will be using your comments as part of my lesson plan.

We will be attending a performance of the work on November 1 by the Cincinnati Symphony.

Do we know who conducted and played the first recording of Schumann symphony No. 3?

Kenneth,

Do you believe the fourth movement is a throwback to earlier music? The use of 4/2 at the outset along with the obsessive polyphony (not to mention the renewed interest in composers like Bach) would seem to lend support to this notion.

Hi David

Yes- very much like late Beethoven and late Mozart, you see Schumann here incorporating some of the techniques and symbols of earlier music in a way that creates something very ahead of its time. It’s not far in way from the slow movement of Beethoven’s op 132, but the mono-thematic nature of the Schumann makes it even more forward-looking.

I believe you meant 1841, not 1941, for the Spring Symphony; overall an excellent and informative article!

Yikes – 10 years before anyone spotted that typo. Thank you.