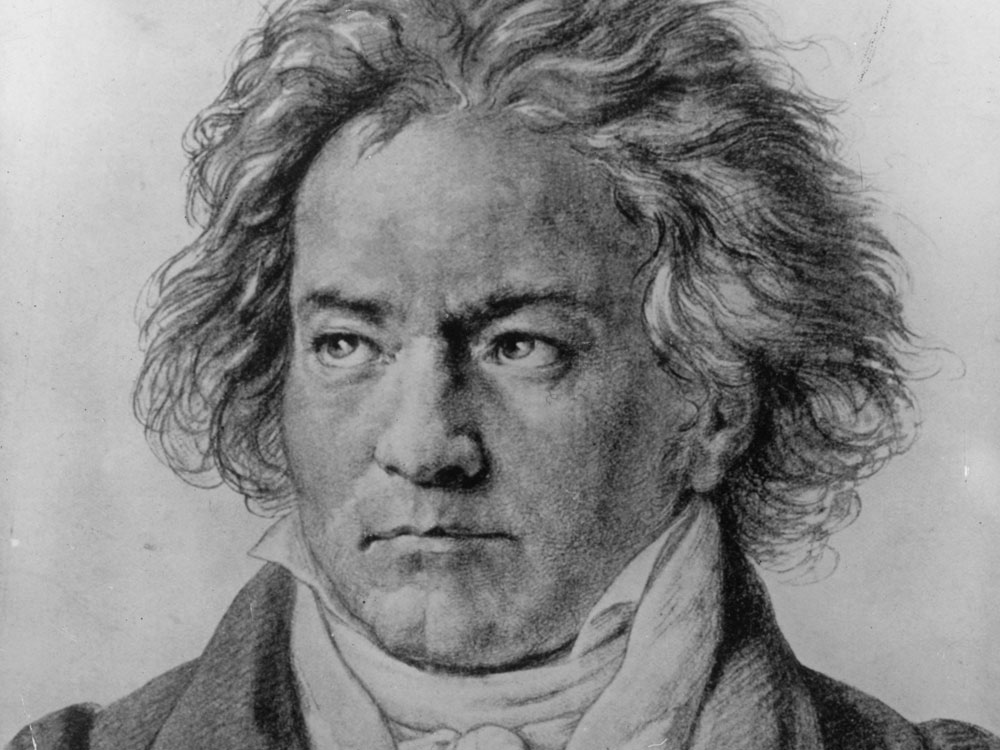

Beethoven (arr. Mahler)- String Quartet in F minor, op. 95 “Serioso”

We often think of Beethoven as having three basic styles that he went through in his career- the early style of the op. 18 quartets, the early piano sonatas and the 1st and 2nd symphonies, then the great middle style typified by the 3rd and 5th symphonies as well as the op 59 quartets, the Violin Concerto and the 4th and 5th piano concerti, and finally that late style as heard in the op 110 and 111 piano sonatas, the 9th Symphony and the late quartets.

In doing so, listeners might easily overlook a small, but vitally important and fascinating, period of Beethoven’s career that took place during the difficult years of transition between the middle and late periods of his life. It is fascinating to look through the catalogue of Beethoven’s middle period and to see where the most astonishing masterpieces must have been sitting on his desk at the same time. The Fourth, Fifth and Sixth symphonies and the Violin Concerto, for instance, were all written at virtually the same time.

However, after this flowering, Beethoven faced an extended personal and professional crisis, and during this nearly-decade-long struggle, he wrote very little. What he did write, however, remains fascinating. Perhaps the greatest typical feature of the middle period, particularly works like the Violin Concerto, was Beethoven’s tendency to stretch forms to their absolute limit. The first movement of the Violin Concerto is 30 minutes long, nearly twice the length of the F minor String Quartet performed this evening.

In the works of this transitional period, Beethoven not only abandons extended structures, he abandons long musical gestures. Phrase lengths tend to be shortened, transitions, when there are any, are abrupt. It is as if he has removed all the padding and ornamentation from the music and left only what he felt was most essential. This “Serioso” quartet and the last two cello sonatas, which are typical of this period, are among his most direct and intense works- intense even by Beethovenian standards. It is music from a genius in the midst of an intense personal and artistic crisis.

The first movement is a brusque Allegro which contrasts a violent first theme which lasts only a few seconds with a gently lamenting chorale theme, which likewise only lasts a few bars. The movement is dramatic and explosive in a character reminiscent of the first movement of the 5th Symphony, but all the drama is over in only four minutes- less than the length of the introductions to the 4th or 5th piano concerti or the Violin Concerto.

The second movement, marked Allegretto, takes the place of a slow movement, and is one of Beethoven’s most perfect creations. A simple march theme in the cellos sets up a soulful melody in the first violins, followed by a haunting fugue. These three ideas are developed with exquisite completeness in just a few short minutes.

The third movement functions like a scherzo, but Beethoven is not joking around- his tempo marking is “Allegro assai vivace ma serioso.” The theme of the main section is one of his most rhythmically complex creations, the trio is a wondrous chorale accompanied by a gentle perpetual motion in the first violin.

The finale begins with the only really slow music in the piece- seven bars of the most chromatic and despairing music imaginable. The main part of the finale that follows is in a rather sad and lyrical character- the darkness of this quartet seems boundless at times. However, the coda is one of Beethoven’s most startling turns. For the first time in the work, he turns to F major, and music that is almost frivolous in nature. The contrast is so great and the change so sudden and incomprehensible that one cannot help but feel there is a sort of bitterness in the laughter of this ending, as though Beethoven is telling us that life is a bit of a joke.

This piece was one of three string quartets that Mahler arranged for string orchestra during his early years at the Vienna Philharmonic (the others were Beethoven’s op 131, which is lost, and Schubert’s Death and the Maiden). Of the three, this is the only one to have been performed by Mahler, although the premiere was a near fiasco, with hecklers booing loudly throughout and condemning Mahler for tampering with the music of Beethoven. In fact, Mahler made the arrangement with great restraint, adding a bass part only in a few sections (the author has actually expanded the bass part considerably for this performance) and he changed none of Beethoven’s music.

Mahler’s arrangement of the Serioso was premiered on a Vienna Philharmonic concert on the 15th of January, 1899. The concert also included Mahler’s new orchestration of Schumann’s First Symphony. The performance of the Beethoven was interrupted by so much booing, that Mahler sent two members of the orchestra into the audience to eject the two most vociferous complainers. With the exception of Eduard Hanslick, critical reaction was overwhelmingly negative. Mahler cancelled the planned performance of Beethoven’s opus 131 Quartet and never conducted the Serioso again. Maher’s score and parts remained undisturbed in the archives of the Vienna Philharmonic until the autumn of 1986, when composer David Matthews sought them out and set about preparing a usable version for performance.

c. 2007 Kenneth Woods

Hi Kenneth, I very much like your Program Note for Op.95. Is it at all possible to re-print it with due acknowledgement? Thank you for giving consideration, Brendan