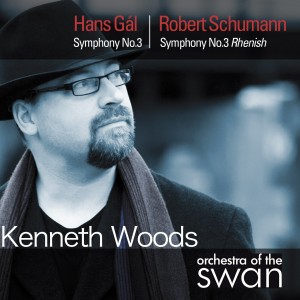

From ClassicalSource, a new review by Colin Anderson of Bobby and Hans vol. 1.

Gál’s Third Symphony (completed in 1952), in A (but it could major or minor) opens winsomely with an expressive oboe solo, the music sometimes harmonically curdling in bittersweet fashion, English ears being reminded of Gerald Finzi, antennae attuned to musical matters that are further afield also being aware of Franz Schmidt (a fellow-Viennese of Gál’s) and, to a lesser extent, Paul Hindemith. After a lengthy, flowing introduction, the bulk of the substantial (14-minute) first movement is waltz based, one more troubled than from Vienna’s golden past. Contrasts of mood and tempo abound – turmoil and nostalgia – and a gentle flute solo offers some solace (and recalls Prokofiev). Like the first, the slow movement opens softly and again features the oboe, lullaby-like, suggesting a boat on a lake on a summer’s day; such placid contentment is contrasted by quicker if still-light sections; Honegger’s Pastorale d’été is recalled. The finale is firm of direction if unsure of mood, the speed is sprightly but there are dark clouds on the horizon, sunshine sometimes breaking through until a clarinet spirals the music on to a brighter future and conclusion (among the many subtleties of orchestration is a getting-slightly-louder from nowhere roll on a cymbal)….

The ‘Rhenish’ Symphony is given a superb outing, gloriously joyous in the outer movements, exuberant without being pushed, and also generously lyrical when needed, not least in the triptych of middle movements, beautifully phrased and sounded, breathing and shapely, sensitively addressed and lovingly detailed. The fourth movement (whether concerned with Cologne Cathedral or not) is suitably solemn to which the nonchalantly tripping finale is the perfect foil. Orchestra of the Swan is of chamber proportions, just the right size for the sort of lucidity that suits Schumann’s music and sitting well in the generous acoustic of Stratford-upon-Avon’s Civic Hall to avoid sounding anaemic. Woods, with violins either side of him and a master of Schumann’s small print, trusts the composer and leaves in no doubt that the allegation that he couldn’t orchestrate is bunkum. As for alternative recordings of the ‘Rhenish’, Woods holds his own against such wonders as Sawallisch (Dresden rather than Philadelphia), Celibidache (Munich), Giulini (Chicago) and immediately becomes a favourite for this delectable work. (Emphasis added)

Throughout, the members of Orchestra of the Swan are willing souls, as content in the new-found Gál as they are with the old-friend Schumann, and both works are excellently recorded. Bring on the next three volumes!

Recent Comments