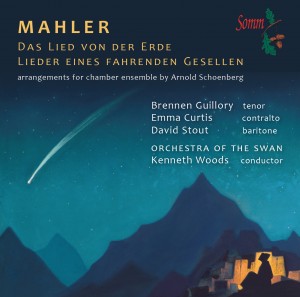

Celebrating the release of SOMM Recording’s new CD of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde and Lieder Eines fahrenden Gesellen, we begin a new series of essays and podcasts exploring Mahler’s Song of the Earth. You can explore Mahler’s masterpiece in depth through past and future Vftp posts and essays, listen to audio samples and podcasts and read recent reviews, interviews and features at the Song of the Earth micro-site here.

Our first new essay is from Mahler scholar and regular Vftp contributor, Peter Davison. In it, he talks about Mahler’s relationship with nature as expressed in his first and last song cycles.

Purchase here from Presto Classical

Mahler seeks the Earth’s embrace

“How can people forever think that Nature lies on the surface? Of course it does, in its most superficial aspect. But those, who in the face of Nature are not overwhelmed with its awe and its infinite mystery, its divinity – these people have not come close to it.”

Gustav Mahler in Recollections of Gustav Mahler (1923) by Natalie Bauer-Lechner

Mahler often told his biographer Natalie Bauer-Lechner that most people lack any true sense of Nature. But what did he mean by this? His complaint was against those who treated Nature as merely picturesque. Nature, he believed, in its deepest aspect is something sublime, which offers us a glimpse of the divine mind. Mahler felt that the cult of the picturesque made Nature subservient to human values. If we only look at its pretty surface, we lose the profound sense of its creative abundance and unpredictable wildness. Mahler believed that, if we become one with Nature, we can transcend the banality of ordinary living and petty human concerns.

Mahler was an avid walker in the Austrian countryside and found inspiration for his music among its woods, lakes and mountains. The landscape was the womb of his creative life, and he approached Nature with religious awe. Das Lied von der Erde expresses his wonder for Creation; a wonder which went beyond anything that words could ever express. Such a religious response to Nature was common among the romantic composers, poets and painters of the nineteenth century. For William Wordsworth, for example, Nature was evidence of the world’s soul; an essentially feminine and maternal entity. It was a view shared by Goethe, whose telling of the Faust myth explored Man’s diabolical pact with power, which brings him into opposition with Nature. Only erotic love, the redeeming influence of the Eternal Feminine, can save Faust from eternal damnation. Undoubtedly this idealisation of Nature was a reaction against the urbanisation and industrialisation beginning in Europe at that time, as a consequence of the new rationalism associated with The Enlightenment. As people’s lives drifted further from the everyday experience of natural phenomena, so artists were inclined to worship at Nature’s pagan altar to compensate for an increasingly rational age. The Romantics found inspiration communing with Nature, which for them was the dwelling place of the muse. The intimate stirrings of their souls were symbolised as divine womanhood – the Goddess or the Eternal Feminine.

Mahler and his guiding light Beethoven, stand at either end of the Romantic period in music, revealing a changing attitude to Nature. Since the Enlightenment, at the end of the eighteenth century, progress in science allowed the curious to observe the incredible patterns and interdependent systems of Nature. For a pre-Darwinian and less sceptical age than our own, this was evidence of a divine plan, but it was also an objectification of Nature which risked disenchanting life and destroying religious feeling altogether. The Romantic response to science and the bold claims of social progress was to idealise the irrational and the primitive, especially Nature. An artist such as Beethoven, who was a child of the Enlightenment, as much as he was any kind of Romantic, reflected a bit of both attitudes. The poet Schiller summarised this tension in his famous tract of 1795, “On Naïve and Sentimental Poetry”. A poet could either be at one with Nature in a state of naïve, child-like wonder, or he could be sentimental towards it, seeking it as something lost. Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony for example belongs more to the naïve way of relating to Nature, and only in the powerful storm scene is the idyllic atmosphere interrupted. Beethoven responded with innocent delight to the natural world, but he also felt the wonder of the rational idealist, sensing a reassuring objective order in Creation which was then mirrored in the classical design and internal logic of his symphony. In Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, the dissenting and subjectively human voice falls largely silent and Nature appears to go its own way.

The Vienna of 1800 was not the sprawling, multi-ethnic, industrial city of Mahler’s time, so Beethoven could afford to be naïve about Nature in this way. He lived in pre-technological era, when most of the population were still peasants. His picture of Nature, to our mind, suggests a timeless Arcadia; a delightful landscape, free from the troubles of everyday urban interactions, even if the storm scene reveals Nature’s more threatening side. Compared to this, Mahler’s view of Nature is more ambivalent. He lived in less confident times, and his music is often “sentimental” according to Schiller’s terminology. In Mahler, Nature is presented both as an Arcadia recalled or longed for, but also as an inhuman, terrifying presence. The Pastoral Symphony might even represent the lost paradise for which Mahler’s Song of the Earth grieves and which it yearns to restore. Prior to the work’s composition, Mahler’s ailing health meant he had to curtail his ambitious hikes in the mountains. He had to turn inside himself to find the spiritual solace which his walks had previously provided. In The Song of the Earth, Mahler’s relationship with Nature becomes deeply personal, even mystical. The composer enters into dialogue with Nature as a living intelligence, filled with meaningful symbols and messages from the beyond. Nature is a state of subjective otherness which increasingly sheds any connection to the ordinary human world.

But what can Mahler teach us about our relationship with Nature? Nature now appears to threaten us. We live in a society faced by global warming, over-population and potential environmental catastrophe. Only science appears to offer any answers. In this context, playing the music of the past might seem like Nero fiddling while Rome burns. Of course, we can treat these works as if they are picturesque; a pleasant saunter in a country park. But, if we approach them with the same reverence and sensitivity which Mahler felt, engrossed as they were in the inner reality of Nature, the music reveals its secrets. We find a paradigm for harmonious unity with Nature which recognises the invisible connections and interdependency between all things. In our modern lives, we are too busy and too cut off from Nature’s wildness to relate to it with true understanding. Do we treat wild places as picturesque or experience them with religious awe? As the bird tells the drunkard in Das Lied von der Erde…”Yes! Spring is here, it came overnight”, but the drunkard responds, “Why does spring matter to me? Let me be drunk!” Mahler suggests that we are all drunk; drunk on consumption and easy pleasure, on human ingenuity and self-importance. We have stopped listening to the bird’s message and pay the price in thoughtless disregard for Nature and the environment.

The most remarkable feature of Mahler’s relationship with Nature is its consistency throughout his creative life. Even in an early work, like the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, Nature is the backdrop and a major agent of the song cycle’s narrative. The wayfarer seeks a naïve, idealised relationship with Nature, but his woundedness intrudes upon his good feeling. Then Nature soon appears indifferent and cruel. Yet a bird is once again the harbinger of some deep truth beyond words which should provide healing and comfort. In a further parallel to Das Lied von der Erde, the final bars of the Wayfarer cycle allude to the dissolving of boundaries and a return to the embrace of Mother Earth. Nature is once more a refuge from the corruption of ordinary human existence; a return to innocence and wholeness. But it is also true that much of Mahler’s symphonic output struggles with Nature as the source of creative urges which are wild and formless, at times threatening to overwhelm the human individual. The creative artist is compelled wrestle his inspiration into shape for, in Mahler’s mind, Nature was also the blind Schopenhauerian Will; something cold and inhuman, as much as it could be warm, beautiful and consoling. Mahler understood that Nature holds up a mirror to the human soul and, for that reason, how we relate to it tells us much about our spiritual condition.

Issues of pollution and conservation, the exploitation of natural resources and climate-change are today on everyone’s mind. We feel powerless, reminded that Nature has the upper-hand. Great music surely has a role to play in changing hearts and minds because, like Mahler’s bird, it tells us who we are and where we belong with an eloquence beyond words. Nature does not lose its sublime qualities, just because we ignore them. We have all at some moment been overwhelmed by the blueness of the sky on a spring day, imagining what fulfilment may lie beyond the shimmering horizon. That is to experience the sublime, some sense of the infinite possibilities within us and, above all, to have a profound sense that we belong on this Earth. What is more, images of the Earth seen from outer-space have shown us its captivating beauty amidst the vast darkness of the cosmos, compelling us to see our planet as fragile and finite. For all that science can teach us, the Earth’s existence and ability to sustain life remain unfathomable mysteries. This is what Mahler wished to convey, but which so much of our consumption-driven lives seeks to deny.

Peter Davison

Wonderful post, Peter.

It seems to me like there is an easily traceable and hugely important evolution in Mahler’s relationship with nature throughout his output. In the first symphony, it is largely a source of joy and wonder (although the sense of longing for Spring in the 1st mvt is very intense and already in those pages you start to sense the kind of stillness that becomes so important, but by the 3rd, it is a far more complex and in many ways more wary relationship. Nature has become something wild, primal and vaguely menacing. So too some of the spooky forest music in the 1st two movements of the 4th.

In both of these works, and in the last of the Kinderotenlieder, salvation involves an escape from the menacing forces and obscure motives of nature

This sense of isolation and threat, as well as a sense of loneliness which is heightened by the juxtaposition of the smallness of the individual in the vastness of the wilderness, is a powerful presence in Ensame in Herbst and the opening of Der Abschied.

All this makes the ending of Der Abschied all that much more incredible. Whereas in all his earlier works there has been this tension between nature and divinity, between the Earthly and Heavenly life, in Abschied, he is able to finally reconcile those tensions. Rather than escaping Nature through God, the narrator returns to Nature, becomes one with Nature.