Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky seemed to be singularly unlucky in choosing the dedicatees of his great concertante works. He wrote his evergreen Variations on a Rococo Theme for the cellist William Fitzenhagen. As always, Tchaikovsky invited Fitzenhagen to suggest improvements to the solo part, but Fitzenhagen went far further- he re-ordered the variations, cutting one entirely. Amazingly, it was Fitzenhagen’s version of the piece that was first published, much to Tchaikovsky’s outrage, and even more incredibly, Tchaikovsky’s original has only begun to replace Fitzenhagen’s version in the last fifteen years.

Things went even worse when Tchaikovsky presented his Violin Concerto to its original dedicatee, Leopold Auer. Auer couldn’t even be bothered to suggest improvements to the violin writing. Instead, Auer dismissed the work as an unplayable monstrosity. Fortunately Tchaikovsky knew the piece’s true value, and went ahead with a premiere by the violinist Adolph Brodsky, and the work quickly became very popular. Auer was eventually shamed into taking up the piece, but he made extensive cuts in the Finale and rewrote several passages against Tchaikovsky’s wishes. Auer was one of the greatest pedagogues of all time—his students included Mischa Ellmann, Nathan Milstein and Efram Zimbalist—and his influence as a pedagogue has meant that many violinists descended from the “Auer school,” including modern soloists as eminent as David Oistrakh, have continued to use his cuts and rewritten passagework to this day.

However difficult these experiences were for Tchaikovsky, they didn’t seem to cause him nearly the distress brought on by his abortive collaboration on the First Piano Concerto with Nikolai Rubinstein. Nikolai Rubinstein was the younger brother of the composer Anton Rubinstein, and a co-founder of the Moscow Conservatory (the Rubinstein brothers were not related to the 20th century piano virtuoso Arthur Rubinstein).

Tchaikovsky had high hopes and specific expectations for his collaboration with Rubinstein on his First Piano Concerto. He had tremendous admiration for Rubinstein’s musicianship and pianism and had every confidence that Rubinstein would play the piece magnificently. He also hoped the Rubinstein could help him to fine-tune the piano writing. Tchaikovsky was a serviceable pianist, but felt the work needed the input of a virtuoso to ensure it was as effective and pianistic as possible.

When the Concerto was completed, Tchaikovsky invited Rubinstein and a few friends for a play-through. Tchaikovsky’s description of the evening three years later to his patroness Nadezzha von Meck still brims with righteous anger.:

I played the first movement. Not a single word, not a single remark! If you knew how stupid and intolerable is the situation of a man who cooks and sets before a friend a meal, which he proceeds to eat in silence! Oh, for one word, for friendly attack, but for God’s sake one word of sympathy, even if not of praise. Rubinstein was amassing his storm, and Hubert was waiting to see what would happen, and that there would be a reason for joining one side or the other. Above all I did not want sentence on the artistic aspect. My need was for remarks about the virtuoso piano technique. R’s eloquent silence was of the greatest significance. He seemed to be saying: “My friend, how can I speak of detail when the whole thing is antipathetic? I fortified myself with patience and played through to the end. Still silence. I stood up and asked, “Well?” Then a torrent poured from Nikolay Grigoryevich’s mouth, gentle at first, then more and more growing into the sound of a Jupiter Tonana. It turned out that my concerto was worthless and unplayable; passages were so fragmented, so clumsy, so badly written that they were beyond rescue; the work itself was bad, vulgar; in places I had stolen from other composers; only two or three pages were worth preserving; the rest must be thrown away or completely rewritten. “Here, for instance, this—now what’s all that? (he caricatured my music on the piano) “And this? How can anyone …” etc., etc. The chief thing I can’t reproduce is the tone in which all this was uttered. In a word, a disinterested person in the room might have thought I was a maniac, a talented, senseless hack who had come to submit his rubbish to an eminent musician….

I was not only astounded but outraged by the whole scene. I am no longer a boy trying his hand at composition, and I no longer need lessons from anyone, especially when they are delivered so harshly and unfriendlily. I need and shall always need friendly criticism, but there was nothing resembling friendly criticism. It was indiscriminate, determined censure, delivered in such a way as to wound me to the quick. I left the room without a word and went upstairs. In my agitation and rage I could not say a thing. Presently R. enjoined me, and seeing how upset I was he asked me into one of the distant rooms. There he repeated that my concerto was impossible, pointed out many places where it would have to be completely revised, and said that if within a limited time I reworked the concerto according to his demands, then he would do me the honor of playing my thing at his concert. “I shall not alter a single note,” I answered, “I shall publish the work exactly as it is!” This I did.

The man who came to the rescue would at first glance to seem an unlikely champion for this most Russian of concerti. Han von Bulow was a towering figure in the German musical world. Early in his career he had established himself as one of the great pianists and conductor’s of his day, and had married into musical royalty, winning the hand of Franz Liszt’s daughter Cosima. He came to be Richard Wagner’s preferred conductor, leading many still-legendary first performances of Wagner’s operas, but their reputation soured when Wagner seduced Cosima, who became Wagner’s second wife. Bulow later became very close with Brahms, particularly through their work together with von Bulow’s chamber orchestra at Meiningen, where Bulow’s extraordinary ensemble offered a perfect library to prepare early performances of most of Brahms mature orchestral music.

But Bulow was no strident nationalist, and he had taken a keen interest in the music of Tchaikovsky. The two men met in 1974 and quickly warmed to each other. After the debacle with Rubinstein, Tchaikovsky sent Bulow the new Concerto, and Bulow’s response was as effusive as Rubinstein’s had been vitriolic. In the end, plans for a Moscow premiere by Nikolai Rubinstein were dropped in favor of a performance in Boston in October 1875, with Bulow as soloist and B.J. Lang conducting a pick-up ensemble. Lang’s modest band was only a distant relative of a powerhouse symphony orchestra like the St Petersburg Philharmonic, or the Boston Symphony, which was not founded until 1881. In fact, there were only four first violins available for the premiere.

The international success of the Concerto eventually persuaded Rubinstein of its merits, and he took the piece into his repertoire and played it often. After some time, his relationship with Tchaikovsky healed to the point that Tchaikovsky planned to entrust him with the premiere of his Second Piano Concerto before Rubinstein’s untimely death. Tchaikovsky did finally accept some advice on the piano writing from Edward Dannreuther and Alexander Siloti, and revised the Concerto in 1879 and 1888.

Though the work has always been popular with audiences and most musicians, it has not always been universally admired by critics and musicologists. Many find it problematic that, having conceived one of the most striking and stirring beginnings in any concerto, Tchaikovsky never returns to the music of the opening. However, a careful analysis of the work shows that almost everything that is to follow grows out of motivic cells in the Introduction. In the course of the Concerto, Tchaikovsky quotes several folk songs, including the Ukrainian song “Oy, kryatshe, kryatshe…”as the first theme of the first movement, the French chansonette, “Il faut s’amuser, danser et rire.” (“One must have fun, dance and laugh”) in the second movement and a Ukrainian vsnyanka or greeting to spring in the Finale. Finally the second theme of the Finale is derived from the Russian folk song “Podoydi, podoydy vo Tsar-Goro.” All were melodies that would have been recognizable to Tchaikovsky’s Russian contemporaries, but he also took pains to choose tunes that could be musically connected to each other and to the Introduction.

Perhaps what perplexes so many intellectuals, but has never bothered most listeners, is the subversive way in which Tchaikovsky’s iconic opening intentionally creates all the wrong expectations about what is to come. Where the Introduction is lyrical, passionate and confident, the bulk of the first movement is mercurial, stormy and full of drama and uncertainty, only arriving at a triumphant ending after much struggle.

The Andante simplice that follows is more of an Intermezzo than a proper slow movement, highlighted by a dazzling scherzando middle section. The outer sections are infused with a fluid and effortless poetry, while the middle section exudes quicksilver wit and devil-may-care virtuosity.

Critics of the work have also suggested the Tchaikovsky’s Finale doesn’t provide an adequate counterbalance to the massive first movement, but, in fact, his proportions and the weighting of the musical argument toward the first movement are quite classical. Beethoven’s Violin Concerto, his Emperor Concerto and Brahms’s D minor Piano Concerto all have similarly massive first movements and relatively slight and light-hearted finales. It is the influence of folk music which is felt most keenly in the Allegro con fuoco, both in the in the feverishly driving first theme and the expansive tune which follows. In the end, it is the big tune that emerges triumphant- a perfect companion to that other big tune with which the concerto began.

c. 2012 Kenneth Woods

Your analysis of Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto I has been very helpful. In the past I have performed this concerto with a second piano as the orchestra.

Soon, I am presenting my piano students in a recital. It is my policy to perform in their recitals as incentive to keep working but I don’t play anything too lengthy.

I have found a book, published in 1947, that contains a solo version of this concerto, the length of which is perfect to include in my recital.

Thank you for your interesting and informative site.

Musically,

G. Mary Matteson

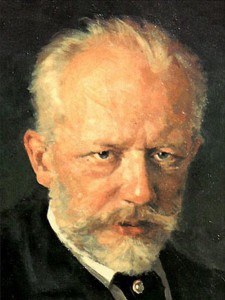

The Tchaikovsky image included near the beginning of this interesting essay appears to come from later in the composer’s life — late 1880’s, perhaps. The First Piano Concerto dates from 1874-75, when Tchaikovsky’s appearance was much younger! Image & caption don’t match, temporally.