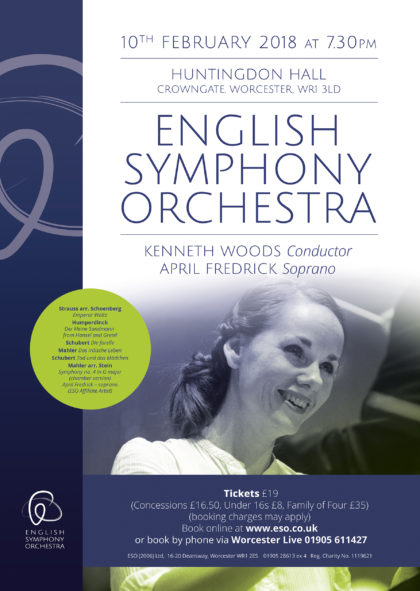

I’m conducting an incredibly cool programme next week with my friends in the English Symphony Orchestra on the 10th of February in Worcester’s lovely Huntingdon Hall. We’re doing Erwin Stein’s magical chamber version of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony with the magnificent soprano April Fredrick. Here are my programme notes about the works on the first half of the concert- Schoenberg’s chamber version of the Emperor Waltz and and my own orchestrations/arrangements of four songs/arias.

I’m conducting an incredibly cool programme next week with my friends in the English Symphony Orchestra on the 10th of February in Worcester’s lovely Huntingdon Hall. We’re doing Erwin Stein’s magical chamber version of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony with the magnificent soprano April Fredrick. Here are my programme notes about the works on the first half of the concert- Schoenberg’s chamber version of the Emperor Waltz and and my own orchestrations/arrangements of four songs/arias.

Booking details for the concert are here.

This is going to be rather special- music as fairy tale for grown ups, child-like-ness as the path the wisdom, nature as both threat and salvation, food as both comfort and torment. Don’t miss it!

About Today’s Concert- Thoughts from the Conductor

The Orchestra

As a name, “The Society for Private Musical Performances” may not roll off the tongue, but it is surely easier to say for most of us than the German original “Verein für musikalische Privataufführungen”. The Society was founded by the composer Arnold Schoenberg with the intention of making carefully rehearsed and comprehensible performances of newly composed music available to genuinely interested members of the musical public. In the three years between February 1919 and 5 December 1921 (when the Verein had to cease its activities due to Austrian hyperinflation), the organisation gave 353 performances of 154 works in 117 concerts that involved a total of 79 individuals and pre-existing ensembles. Devoted to fostering new discussion of emerging works, the Society did not welcome critics, and audience members had to join the Society in order to attend.

Works performed on the Society’s concerts reflected a huge range of the best of late 19th and early 20th Century works, but nothing by Schoenberg himself. Orchestral works were played in arrangements for small ensembles like the one you will hear tonight. Schoenberg himself made many of these arrangements, including the whimsical arrangement of the Strauss Emperor Waltz which opens our concert tonight, and he oversaw the work of other composers and arrangers including Erwin Stein, who arranged the Fourth Symphony of Mahler for a Society concert in 1921.

There was no standard instrumentation for these concerts, but most of the arrangements that have come down to us from the Society are for some combination of solo strings, a few solo winds, piano and harmonium. This sort of salon orchestra was often augmented by the liberal use of percussion, which can greatly enhance the range of colour the ensemble can produce.

For much of the 20th Century, the arrangements of the Society were largely forgotten. In an affluent age, there seemed to be little need for arrangements of Mahler symphonies and songs for 10-15 players. However, in the last twenty years or so, these arrangements have seen a real resurgence, and have become recognised as being artistically interesting in their own right. From a listener’s point of view, they offer a more intimate view of the music, one that perhaps allows the creativity and artistry of the individual performances to shine through. I’ve conducted and recorded a number of the arrangements from the Society and have become thoroughly seduced by their unique sound world. I hope those of you new to this kind of ensemble leave tonight suitably enchanted.

The Songs

Having decided to programme Erwin Stein’s orchestration of Mahler’s 4th Symphony on this concert, I had to give careful thought to what else should be on the programme. Because of their sheer scale, the question of what, if anything, should be on the same concert as a Mahler symphony is not always an easy one to answer. The Fourth is the shortest and slightest of Mahler’s eleven symphonies, but it is still nearly an hour long. In past, I’ve coupled it with everything from a Haydn symphony to the Grieg Piano Concerto, but since we were doing Stein’s reduced orchestration of the Mahler, it seemed silly to programme something for vastly different forces on the first half of the concert. The choice of Schoenberg’s affectionate arrangement of the Emperor Waltz was an easy one- the Fourth is in many ways one of Mahler’s most explicitly Viennese works.

However, not that many arrangements of the Society for Private Musical Performances survive, which made my programming options limited until it occurred to me that if the arrangements didn’t exist to do the repertoire we wanted to do, we could simply make new orchestrations for the same forces as the Stein Mahler Four. Once I had steeled myself to the challenge of making the arrangements you hear tonight, anything was possible.

In the 55 minutes of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony, our wonderful soprano, April Fredrick, only sings for about five minutes, so it seemed obvious that the first half of tonight’s concert should include a selection of songs whose themes resonate with those of the symphony.

Mahler’s Fourth Symphony is primarily a meditation on nature and childhood. It explores, in very profound and sophisticated ways, the complexity of a child’s view of the natural world, with its mixture of threat and wonder.

Humperdinck’s great children’s opera, Hansel und Gretel, a quasi-Wagnerian setting of the classic Brothers Grimm fairy tale, tells the story of two children in peril. The opera was composed in 1891-2. Richard Strauss conducted the first production in 1893, Gustav Mahler the second production in Hamburg in 1894. The adventures of Hansel and Gretel balance moments of deprivation and hardship with wonder, moments of horror with hope. The two selections I have adapted come from Act II, Scene 2. Having become lost in the forest, Hansel tries to find the way back, but he cannot. As the forest darkens, Hansel and Gretel become scared, and think they see something coming closer. Hansel calls out, “Who’s there?” and a chorus of echoes calls back, “He’s there!” Gretel calls, “Is someone there?” and the echoes reply, “There!” Hansel tries to comfort Gretel, but as a little man walks out of the forest, she screams. In the first section you hear tonight, the Sandman (sung by a soprano), who has just walked out of the forest, tells the children that he loves them dearly, and that he has come to put them to sleep. He puts grains of sand into their eyes, and as he leaves they can barely keep their eyes open. Gretel reminds Hansel to say their evening prayer, and after they pray, they fall asleep on the forest floor. My arrangement of this scene is essentially a reduction- wherever possible, I have kept true to Humperdinck’s original, with flute parts on the flute and string parts on the strings, and the harmonium standing in heroically for absent bassoons and horns. In the Evening Blessings, April changes roles from Sandman to Gretel, and our wonderful principal clarinet, Alison Lambert, takes on the role of Hansel.

| Der kleine Sandmann bin ich – st! Und gar nichts Arges sinn ich – st! Euch Kleinen lieb ich innig – st! Bin euch gesinnt gar minnig – st!Aus diesem Sack zwei Körnelein Euch Müden in die cugelein; Die fallen dann von selber zu, Damit ihr schlaft in sanfter Ruh. Und seid ihr fein geschlafen ein, Dann wachen auf die Sterne, Und nieder steigen EngeleinAus hoher Himmelsferne Und bringen hold Träume! Drum träume, Kindchen, träume! Drum traume, Kindchen, traume!(Verschwindet. Volllge Dunkelheit.) .

HANSEL” (sclilaftrunken) .

GRETEL Sandmann war da ! Abends, will ich schlafen gehn, |

I shut the children’s peepers, sh ! and guard the little sleepers, sh ! for dearly do I love them, sh ! and gladly watch above them, sh! And with my little bag of sand, By every child’s bedside I stand ; then little tired eyelids close, and little limbs have sweet repose. And if they’re good and quickly go to sleep, then from the starry sphere above the angels come with peace and love, and send the children happy dreams, while watch they keep !Then slumber, children, slumber, for happy dreams are sent you through the hours you sleep. HANSEL (half asleep).

GRETEL Sandman was there

BOTH: When at night I go to sleep, |

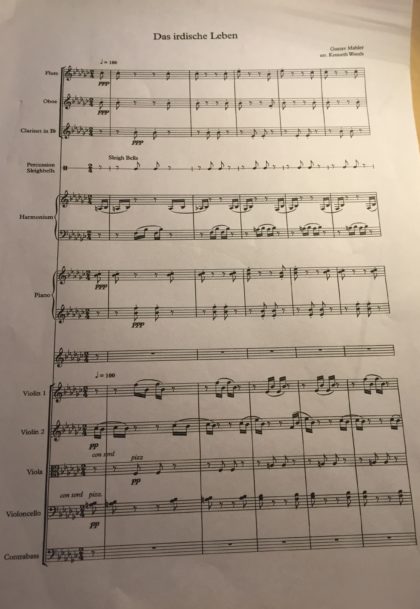

Both Mahler’s 100-minute Third symphony and his Fourth, heard tonight, grew out of the musical material in The Heavenly Life, the short, beautiful song which forms the final movement of the Fourth Symphony, “Das himmlische Leben” or “The Heavenly Life.” In the first half of this concert, we hear his song “The Earthly Life” (“Das irdische Leben”), which forms a sort of bleak mirror to the song that will end this concert. Where “The Heavenly Life” tells us of a world of eternal peace and plenty, “The Earthly LifeT speaks of a world of terror and hunger. As with the Humperdinck, I have essentially stuck as closely as possible to Mahler’s own orchestration of the song, which is a model of clarity and economy. Although he is known for his use of vast forces, Mahler’s natural textural métier is chamber music-like clarity.

Both Mahler’s 100-minute Third symphony and his Fourth, heard tonight, grew out of the musical material in The Heavenly Life, the short, beautiful song which forms the final movement of the Fourth Symphony, “Das himmlische Leben” or “The Heavenly Life.” In the first half of this concert, we hear his song “The Earthly Life” (“Das irdische Leben”), which forms a sort of bleak mirror to the song that will end this concert. Where “The Heavenly Life” tells us of a world of eternal peace and plenty, “The Earthly LifeT speaks of a world of terror and hunger. As with the Humperdinck, I have essentially stuck as closely as possible to Mahler’s own orchestration of the song, which is a model of clarity and economy. Although he is known for his use of vast forces, Mahler’s natural textural métier is chamber music-like clarity.

| Mutter, ach Mutter, es hungert mich! Gieb mir Brot, sonst sterbe ich!“ „Warte nur! Warte nur, mein liebes Kind! Morgen wollen wir ernten geschwind!“Und als das Korn geerntet war, rief das Kind noch immerdar: „Mutter, ach Mutter, es hungert mich! Gieb mir Brot, sonst sterbe ich!“ „Warte nur! Warte nur, mein liebes Kind! Morgen wollen wir dreschen geschwind!“Und als das Korn gedroschen war, rief das Kind noch immerdar: „Mutter, ach Mutter, es hungert mich! Gieb mir Brot, sonst sterbe ich!“ „Warte nur! Warte nur, mein liebes Kind! Morgen wollen wir backen geschwind!“Und als das Brot gebacken war, lag das Kind auf der Totenbahr’! |

‘Mother, oh mother, I’m hungry! Give me some bread or I shall die!’ ‘Just wait! Just wait, my dear child! Tomorrow we shall hurry to harvest!’And when the grain was harvested, the child still cried out: ‘Mother, oh mother, I’m hungry! Give me some bread or I shall die!’ ‘Just wait! Just wait, my dear child! Tomorrow we shall hurry and go threshing!’And when the grain was threshed, the child still cried out: ‘Mother, oh mother, I’m hungry! Give me some bread or I shall die!’ ‘Just wait! Just wait, my dear child! Tomorrow we shall hurry and bake!’ And when the bread was baked, |

Franz Schubert was, and always will be, the greatest exponent of the art song in human history. His output in song is without match in breadth, beauty, originality and importance. His songs were to be a huge influence on the creative development of Gustav Mahler. Mahler’s first masterpiece, the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, or Songs of a Wayfarer, are hugely Schubertian in both their musical language and their subject matter. “Die Forelle” (“The Trout”) is one of Schubert’s simplest and most popular songs, composed in 1817, when Schubert was just 20, to words by Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart. The song later formed the basis of a set of variations which gave Schubert’s 1819 work for violin, viola, cello, double bass and piano, its name: the Trout Quintet. The song’s three verses tell the story of a child observing a fisherman at work, and her outrage when the fisherman muddies the water, driving the trout from the safety of the rocks onto the waiting hook. The fourth stanza, which Schubert didn’t set, makes clear that the song is, in part, a parable of innocence lost and a cautionary tale for young girls:

You who tarry by the golden spring

Of secure youth,

Think still of the trout:

If you see danger, hurry by!

Most of you err only from lack

Of cleverness. Girls, see

Seducers with their tackle!

Or else, too late, you’ll bleed

Heard in its context tonight, I think the song speaks again to the child’s view of our complex relationship with food and comfort, and the cost of that food and comfort. One couldn’t blame the father of the starving child in The Earthly Life for muddying the waters in order to feed his family. The child is outraged for the trout, but only because she clearly doesn’t know the pain of hunger.

| In einem Bächlein helle, Da schoss in froher Eil’ Die launische Forelle Vorueber wie ein Pfeil. Ich stand an dem Gestade Und sah in süsser Ruh’ Des muntern Fishleins Bade Im klaren Bächlein zu.Ein Fischer mit der Rute Wohl an dem Ufer stand, Und sah’s mit kaltem Blute Wie sich das Fischlein wand. So lang dem Wasser helle So dacht’ ich, nicht gebricht, So fängt er die Forelle Mit seiner Angel nicht.Doch endlich ward dem Diebe Die Zeit zu lang. Er macht das Bächlein tückisch trübe, Und eh’ ich es gedacht So zuckte seine Rute Das Fischlein zappelt dran, Und ich mit regem Blute Sah die Betrog’ne an. |

In a clear little brook, There darted, about in happy haste, The moody trout Dashing everywhere like an arrow. I stood on the bank And watched, in sweet peace, The fish’s bath In the clear little brook.A fisherman with his gear Came to stand on the bank And watched with cold blood As the little fish weaved here and there. But as long as the water remains clear, I thought, no worry, He’ll never catch the trout With his hook.But finally, for the thief, Time seemed to pass too slowly. He made the little brook murky, And before I thought it could be, So his line twitched. There thrashed the fish, And I, with raging blood, Gazed on the betrayed one. |

Schubert’s setting of The Trout is a compact masterpiece, barely more than a minute long. Given the sonic possibilities of expanding the accompaniment from piano to miniature orchestra, I decided to be more interventionist in arranging and expanding Schubert’s song. I have combined the three verses of the song with several, but not all, of the variations in the Trout Quintet. I’ve chosen to alternate strophes of the song with variations from the quintet that I thought suited the mood of the lyrics. In addition to knitting together the song and the quintet, I’ve had to transpose the song from its original key (D-flat major) to the key of the variations (D major) and I’ve performed a bit of harmonic surgery on the variations to make sure the new work flows in a logical way. The most drastic change, which will probably upset the purists and go unnoticed by everyone else, is that I have changed the key of lovely cello variation from B-flat major to D major. Unlike the Humperdinck and the Mahler, there was no orchestral original to work from here, so I’ve orchestrated the piano accompaniment of the song and gently expanded the instrumentation of the Quintet as needed.

Finally we come to another combination of song and variations by Schubert, both known as “Der Tod und das Mädchen” or “Death and the Maiden.” The song is based on a poem by Matthias Claudius and was written in 1817, the same year as “The Trout.” It has only two verses- one in which the Maiden pleads with Death to pass her by, and one in which Death assures her that he is a friend.

| Das Mädchen: Vorüber! Ach, vorüber! Geh, wilder Knochenmann! Ich bin noch jung! Geh, lieber, Und rühre mich nicht an. Und rühre mich nicht an.Der Tod: Gib deine Hand, du schön und zart Gebild! Bin Freund, und komme nicht, zu strafen. Sei gutes Muts! ich bin nicht wild, Sollst sanft in meinen Armen schlafen! |

The Maiden: Pass me by! Oh, pass me by! Go, fierce man of bones! I am still young! Go, rather, And do not touch me. And do not touch me.Death: Give me your hand, you beautiful and tender form! I am a friend, and come not to punish. Be of good cheer! I am not fierce, Softly shall you sleep in my arms! |

In 1824, Schubert used the song (in particular, the introduction of the song), as the basis of a set of variations which would become the slow movement of his String Quartet in D minor, one of his greatest chamber music works. Mahler’s love for the Quartet was enormous- it was one of two string quartets (the other was Beethoven’s “Serioso” Quartet) that Mahler orchestrated for performance by the full strings of the Vienna Philharmonic. This arrangement, like the others for flute (doubling alto flute), oboe (doubling cor anglais), clarinet (doubling bass clarinet), percussion, harmonium, piano and solo strings, starts with an exact lifting of the beginning of the slow movement of the Death and the Maiden Quartet, but wanders pretty far from the soundworld of Schubert’s two originals.

It’s not uncommon these days for one to hear a performance of the Lied, Death and the Maiden as a prelude to a performance of the complete quintet. I’ve chosen a different approach. As I alluded to above, the entirety of Mahler’s Fourth Symphony can be viewed as a development of the ideas in the song that concludes it. Rather than weave together song and variations of Death and the Maiden as I have with The Trout, I’ve orchestrated the entire slow movement of the string quartet except for the last bar, then orchestrated the song to come at the end. Structurally, it’s not all that different than the Mahler symphony- we hear the basis of everything at the end instead of at the beginning.

Death tells the Maiden to “Be of good cheer!” Does he speak the truth? Schubert’s tender coda is a hopeful clue that consolation awaits her.

Did you by any chance get a live recording of this program? I would love to hear your reimagined Schubert and Mahler songs!

Sadly, no recording this time, but hoping we might record it properly at some point in the future.

Ken – a practical question: do you actually use a harmonium (which to my knowledge in 15 years’ conducting I can’t ever recall even *seeing*, let alone finding for hire)? If not, what do you use instead please?

Many thanks. Fascinating notes, too. Love these arrangements.

Hi Tom

Yes- we did use a real harmonium for these concerts, and I also did for my 2010 recording of the chamber Das Lied and Leider eines fahrenden Gesellen with Orchestra of the Swan.

Your best bet in the UK is

http://harmoniumhire.co.uk

It’s worth the effort and expense to have a real instrument that exists in the same acoustic space as the rest of the band. Such an evocative and colourful sound.