Vibrato has been a subject of lively debate in the discussion of performance practice for a couple of generations now, but usually when we talk about orchestral vibrato, we mean string vibrato, and, usually, we’re talking about abstaining from said string vibrato.

This often leads to some very strange musical outcomes when modern orchestras get all the strings playing a Beethoven symphony or concerto without vib while the woodwinds wobble away as usual. How is that musically credible? And when you add vocal soloists, the effect can be even more nonsensical, even comical. It just goes to prove that it’s easier to tell 20 world-class section violinists to abstain from the vibrato they spent thousands in music school learning to acquire than to ask for the same from a rogue flutist or soprano. Or maybe it’s also hard to convince a stubborn principal string player to set aside the views on historical performance practice and listen to the soloist they are accompanying and try to match?

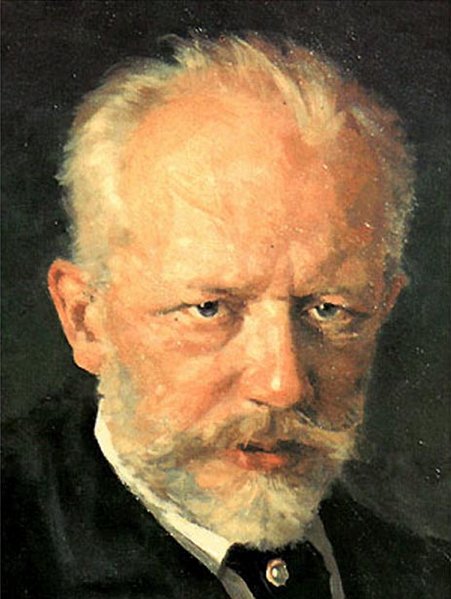

But in some traditions, there is strong evidence that we should be more aware of the use of vibrato in other sections. In both the Czech and Russian traditions, there is a rich vocabulary of brass vibrato (generally not wanted in the USA, UK and Western Europe) which you can hear in the very orchestras which only a few generations earlier were premiering the major works of Dvorak and Tchaikovsky in partnership with those composers.

If you listen to this recording of Leningrad (St Petersburg) Philharmonic (the oldest orchestra in Russia) looking for brass vibrato, you’ll have to be patient. They use it selectively and with great control, but the warm vibrato in the famous horn solo in the 2nd movement gives it a vulnerability and humanity which is really special. It’s a pity we don’t hear more of this kind of playing in the West and it seems to be going extinct in the East. And when trumpets turn on the vibrato at key moments, it adds real ecstatic energy to the sound.

I’m teaching this incredible symphony to the second incarnation of the ESO Youth Orchestra this week. Mravinsky’s interpretations of Tchaikovsky are both radical and, after 60 years since they first appeared on LP, nearly canonical. More than anything, he shows how much more powerful this music is when you play it with real respect for the text and without any self-indulgent sentimentality. Perhaps in some of the slow music, that lack of sentimentality tips over into a lack of space and colour, but there are plenty of other conductors you can go to who bring a warmer heart to this music. Likewise, his main tempo in the last movement, while exciting, doesn’t have much to do with Tchaikovsky’s actual markings. He manages to rob himself of the possibility of realising those passages (piu animato, Molto vivace and Presto) which Tchaikovsky says should be faster than the main Allegro vivace.

But Mravinsky brings fire, precision and intensity, and that’s a potent combination in Tchaikovsky.

It’s a good question about vibrato. I guess another factor is hardware. The Russian orchestras back in the days of Mravinsky, Svetlanov and Kondrashin were using narrow bore brass instruments. I’m not sure the vibrato would work so well with today’s brass instruments.

Hi Mattias

You make a very good point, and I think, actually, that Tchaikovsky is a composer where performance on original instruments is a very worthwhile idea. Some of the wide bore instruments are so loud and heavy and powerful that they make a proper string/brass balance close to impossible even setting aside the question of vibrato. Tchaikovsky’s reputation as a ‘bombastic’ composer is really unfair. The Fifth is actually a very classical symphony, with the relationship between the wind, brass and string choirs intended to be equal.

This concert hall (The Grand Hall of Saint Petersburg Philharmonia) is like a holy shrine to me. I heard many excellent concerts there during my study time in St. Petersburg, and the acoustics IMHO is the best in the world, not to mention the atmosphere. I have yet to perform there myself, but someday I will!

I prefer Monteux/Boston in Tchaikovsky 5. But I do love that brass vibrato. I have to imagine that eventually there will be a Russian equivalent to Les Siecles which specializes in authentic performance of Russian music – Currentzis sort of does it with Anima Eterna but his main focus is obviously elsewhere and unlike the French tradition, it’s not entirely dead yet.

Hi Evan

I’ll have to find the Monteux. He was great it almost everything.

I remember hearing the “sort of does it” conductor you mention doing the Tchaik Violin Concerto and thinking it was the most perverse and horrifically wrong headed thing I’d ever heard in my life. Just a complete, monstrous bastardisation of a beautiful work. I confess I didn’t get through the whole thing, but I couldn’t. It felt a sick musical joke. I shudder to think what he would do to the 6th Symphony!

Lucky you getting to spend so much time there!!!!

“Sort of does it” has already recorded Tchaikovsky 6. It’s interesting but quite the opposite of “authentic” with lots of 1970s-style artificial production touches (there even an audible “sigh” at the start of the finale).

In the interest of balance, his Rite of Spring is terrific.

I haven’t yet sampled his perfume (no, I’m not joking….) Hard to imagine Monteux doing something similar except in jest!

Currentzis is the most divisive conductor in the world, Celibidache 2. I have yet to make up my mind because there is clearly so much thought and effort that goes into his interpretations that I think one can’t judge him by a normal critical appraisal. Somebody like Norrington comes to his interpretations by intellectual laziness, but the level of detail in Currentzis is so extraordinary that you certainly can’t accuse him of that, even if you completely disagree with the results. But compared to that Violin Concerto recording, the Tchaikovsky 6 is stunningly normal – like the wonderfully named Mr. Broucek says (have you been to the moon? :) ) it’s a little Soviet sounding but that’s perhaps to be expected when the orchestra is working in Siberia.

My favorite Tchaikovsky 6 recordings are both by Kondrashin, which are very Soviet sounding in the best possible ways, and purely as an interpretation blows Mravinsky out of the water. I’m also extraordinarily fond of late Fricsay and early Gergiev.

I have mixed feelings – Mravsinky’s recordings certainly seem to bring a sense of authenticity and strike me as indigenous, and are even maybe a bit and cold austere at times. I do think, at the same time, Bernstein intrinsically brings so much life and soul to Tchaikovsky – he certainly enhances the polar nature of his music (who can better do it). I think vibrato can, when used contextually, can certainly enhance his writing. I entirely disagree with the person above who purports that the strings, winds, and brass are always balanced in the 5th. As a timpanist I know that he writes some of the loudest dominant pedals in the literature and the brass sounds is bottomless. He was not trying to achieve a balanced orchestra in my mind.