Description

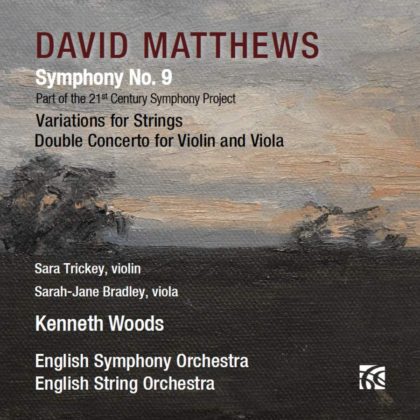

English Symphony Orchestra, English String Orchestra

Kenneth Woods – conductor

Sara Trickey – violin, Sarah-Jane Bradley – viola

Sara Trickey – violin, Sarah-Jane Bradley – viola

Symphony no. 9

Variations for Strings

Double Concerto

“Stunning concert with every piece done to perfection. The superb Sheku Kanneh-Mason in the Elgar. The world premiere of David Matthews’ 9th Symphony. And a terrific orchestration of the Elgar Piano Quintet. Everything presided over by the urbane Kenneth Woods” , James Jolly, Editor-in-Chief, Gramophone , May 2018

“Top Can’t-Miss Classical Concerts of 2018” – The Spectator

“His ninth symphony, receiving its world premiere on this release, is a kind of summation. Starting with a self-composed carol and extending to a Bach chorale, it represents the best of British creativity in its craftsmanship, its moderation and its lucid rationale. The language, while tonal, is two generations beyond Vaughan Williams and the narrative reflects something of a thinking mans struggle to maintain a reasoned equilibrium in a threatened universe. A violin solo in the third movement recalls The Lark Ascending, if only in its distant unattainability. Something of the late symphonies of Malcolm Arnold rises elliptically in the finale. This is a lovely symphony, an altogether personal utterance by a composer who lives and breathes symphonic form, who writes out of love for each and every instrument of the orchestra. Kenneth Woods conducts the sweet serenity that is the English Symphony Orchestra. The five movements are over all too soon in 26 minutes. A set of variations for string orchestra and a double concerto for violin and viola round off the album. I am saving them for the weekend. This is music to hold close and to savour at leisure.” —Norman Lebrecht, Lebrecht Listens, Ludwig Van

“…Matthews’s symphony seems to me to belong instead to that particular British literary tradition, from Gilbert White to Richard Mabey, which finds spiritual renewal in a meticulous and unsentimental observation of nature. The audience at St George’s Bristol — where Kenneth Woods conducted the world première with the English Symphony Orchestra — actually cheered…” Richard Bratby – The Spectator

“David Matthews’ Ninth Symphony is a highly impressive composition. It’s extremely attractive and it’s brilliantly conceived for the orchestra. It’s been well worth the wait to hear this important work which, having made a strong first impression on me, has seemed even better the more I’ve listened to it. The work is splendidly served by Kenneth Woods and the English Symphony Orchestra, who turn in a highly assured performance. This is an important release….” John Quinn – MusicWeb International

“Much of the opening movement does stem from the guileless carol melody that had fired the creative process. Matthews likens it to the naive theme that begins Nielsen’s Sixth Symphony, but where in that work the result is sardonic and almost nihilistic, here the ingenious transformations generate exuberant invention…a work that otherwise manages to seem unmistakably British without ever becoming derivative.” Andrew Clemments – The Guardian

“Some would say the symphony is now a musical outfitters of dead men’s clothes. Matthews contends otherwise in a cycle that has steadily gathered momentum and purpose during the past decade to culminate (for now) in a cogent five movement structure… Dating from 1986, a set of eight variations on a troubled Bach chorale deserves a place in the canon of celebrated English string literature from Purcell through to Elgar, Bridge and Tippett.” Peter Quantrill – Gramophone

Recording of the Month – MusicWeb International “Matthews could scarcely imagine that this recent addition to his symphonic canon will receive superior advocacy than that lavished upon it by the indefatigable Kenneth Woods and his English Symphony Orchestra …this set of Variations amounts to yet another worthy candidate for the burgeoning genre we think of as ‘English String Classics’.” Richard Hanlon – MusicWeb International

“Nature and English Pastoral tradition meeting Mahler and Sibelius” Andrew McGregor, BBC Radio 3 Record Review

“David Matthews is the author of a personal, original, spontaneous and authentic body of work…the most influential exponent of English music after Benjamin Britten and Michael Tippett… The Variations are “a moving composition where the beautiful passages that reflect the talent of the composer are not lacking… The orchestra remains in splendid second form… Kenneth Woods, conductor a reflective director, of intrepid vocation and a refined expressiveness, makes an essential contribution to the British symphonic creation.” Carmé Miro – Sonograma

Five Stars! “…given the chance, many music lovers would embrace this melodic, vigorous and engaging work. Congratulations then to Kenneth Woods, conductor and the English Symphony Orchestra’s “21st Century Symphony Project” for that performance and this recording.” Norman Stinchchombe, The Birmingham Post

” 3 magnificent works masterfully transport the English tradition of Britten, Arnold & Tippett into the 21st century. Sometimes pastoral, always thoughtful, totally absorbing, the supremely confident 9th symphony reveals more depth with each listen. Oh, and it’s got TUNES!!! My Disc of the Week.” Adam Philp – The Symphonist.

Admin –

Pretty much every major symphonist from Brahms to Maxwell Davies leaves a trace on the Ninth Symphony of David Matthews. The inference drawn, however, need not be of a synthetic assimilation. Some would say the symphony is now a musical outfitters of dead men’s clothes. Matthews contends otherwise in a cycle that has steadily gathered momentum and purpose during the past decade to culminate (for now) in a cogent five-movement structure.

In fact, it’s Haydn who comes to mind – no small compliment – in the initial unfolding of a modest carol melody and its unexpected capacity for symphonic heavy lifting. A motivic fragment of the melody then forms the basis of both a pounding, ostinato scherzo and its slower central episode (in four, not a trio), and it doesn’t require perusal of the score to hear the kinship of the carol with a briefer fourth-movement waltz, more pastorally scored but shadowed in the manner of Max (or Hardy or the Eclogues of Virgil for that matter) by a looming threat to the idyll. Fading out inconclusively over Sibelian pizzicato strings, the conflict is fought afresh and won by a good old-fashioned finale over which the carol melody comes to ring out in a C major happy ending.

That leaves the central slow movement – and indeed the six-minute elegy at the heart of the Ninth doesn’t bear the weight of expectation upon such a structural fulcrum. Echoes of birdsong, of Vaughan Williams and Lutos?awski, draw the piece away from the goal of renewal which is the theme of the carol, the symphony and perhaps of Matthews’s symphonic career.

The Ninth Symphony received its first performance at the hands of these performers last year, and at the same time they made this admirable albeit slightly congested recording in St George’s, Bristol. There is more space to the engineering and more finesse to the execution of the two string-orchestra pieces recorded at Great Malvern Priory.

Dating from 1986, a set of eight variations on a troubled Bach chorale deserves a place in the canon of celebrated English string literature from Purcell through to Elgar, Bridge and Tippett. Birdsong returns in the Double Concerto of 2013, which celebrates friendship rather than competition without attaining the sureness of purpose or distinctive profile of its companion works, for all the delicacy and sympathy of the partnership between Sara Trickey and Sarah-Jane Bradley.

— Peter Quantrill, Gramophone

Admin –

From Classical Lost and Found

https://www.clofo.com/Newsletters/C200930.htm

Matthews, D.: Sym 9, Dbl Conc (vn, va & stgs), Vars for Stgs; Woods/Eng SO/Trickley/Bradley/Woods/Eng StgO [Nimbus]

AUDIOPHILE BEST FIND (1 CD)

Five years ago we told you about British composer David Matthews’ (b. 1943) Seventh Symphony (see 14 April 2014), and since then he’s been a busy bee and cranked out two more. This welcome Nimbus release gives us his latest effort in the genre along with two earlier works for strings. These are the only recordings of them currently available on disc.

The concert opens with his five-movement, Ninth Symphony of 2016. The first “Allegro moderato” (“Moderately fast”) [T-1], is in sonata form and starts with a catchy, vernal tune (CV) [00:02] that began life the previous year on the occasion of the 2015 winter solstice. This had prompted David to write his wife a note in the form of a “little carol” with CV as its melody and words about the coming of spring (see the album booklet).

CV permeates the work, thereby making it somewhat of a modern-day Schumann (1810-1856) Spring Symphony (No. 1, 1841). But for now, it’s chromatically explored with occasional drumroll accents and gives way to an antsy countermelody [01:43]. Both ideas then undergo a colorful development with more percussive spicing, followed by a somber version of CV (CS) [04:42]. This initiates a recap coda that ends the movement in wistful tranquility.

As in his Symphony No. 4 (1990), the inside movements consist of scherzos on either side of a slow one. This grouping starts with a “Molto vivace ed energico” (“Fast and furious”) [T-2], which has CV-derived, frenetic, blues-tinged outer sections. They’re wrapped around a laid-back trio [02:05-03:34], and end in “fortissimo” (“forceful”) haste.

The middle “Poco lento e cantabile” (“Somewhat slow and songlike”) [T-3] is a lovely offering that David tells us is an extended version for full orchestra of his string piece, A June Song (2015; currently unavailable on disc). It could almost be a CV afterthought, and has a closing coda [05:27], where an E flat clarinet plays bits of a local thrush’s song he heard while revising this movement.

It’s succeeded by that other scherzo, which is marked “Ombroso” (“Shadowy”) and consequently not as wild as its predecessor. A tiny, delightful waltz number [T-4] set to a pizzicato accompaniment, the music here is a respite before the Symphony’s imposing finale.

Marked “Velato, Urgente” (“Veiled but Urgent”) [T-5], the composer says this was inspired by the Jan Sibelius (1865-1957) Third Symphony’s (1907) last movement. That said, the Matthews begins quietly with a solo violin reminder of CS [00:01], followed by restless, CS-tinged, tremolo-string-accented passages [01:55]. These become increasingly agitated with brass outbursts and fall away into subtle intimations of CV [04:17]. The latter then build into a big tune, brass chorale-like statement of it [05:37] that seemingly ends the Symphony with the triumphant arrival of Spring.

Our performing group is the English Symphony Orchestra (ESO), whose string players wear two hats, considering they also make up the acclaimed English String Orchestra (EStgO; see the selections below). Under their Artistic Director and Principal Conductor, Kenneth Woods, they give a spirited account of this music. Moreover, it must rank as one of the best contributions to the 21st Century Symphony Project initiated by Maestro Woods and the ECO back in 2016.

Made last year in a venue known as St. George’s Bristol, which is a former church in that city, located some 100 miles west of London, the recording presents a generous, well-positioned sonic image in an enriching acoustic. The orchestral timbre is characterized by pleasant highs, a convincing midrange and clean, rock-bottom bass.

Now, it would seem the members of the ESO woodwind, brass and percussion sections go out for a tall one, leaving the EStgO for the two remaining string selections. The first of these is a set of Variations (1986), which is another of those cart-before-the-horse ones (see 30 April 2018), where the composer doesn’t present the main subject (MS) until just before the work’s end. And in that regard, we’ll just say at this point, MS is the melody from a piece by one of Germany’s best-known composers.

The work begins with eight variations, the first (V1) [T-6] being a fidgety treatment of MS that closes with whining violins and grumbling double basses. Then MS is turned into a sad “Sicilienne” (“Siciliana”) [T-7], which ends with a hint of V1, succeeded by two variants that are respectively bizarre [T-8] and ominous [T-9]. Subsequently, Matthews serves up a reverent fifth [T-10] that’s an MS-instilled canon with an underlying, bass-pedal-point and descanting, rhapsodic violin.

After that we get a couple of scherzoesque transformations, the first [T-11] having MS-derived, chromatically capricious, outer sections wrapped around a trio [00:43-01:09] based on a related, yearning motif (MY). Then there’s a fleeting second [T-12] in four “verses”, where the composer successively augments each with an additional part.

A subsequent MY-based chorale prelude [T-13] sets the tone for the pious entrance of MS [T-14], which is none other than the melody for one of old, J.S. Bach’s (1685-1750) Chorales, namely “Die Nacht ist kommen” (“Night’s darkness falleth”, BWV 296, date unknown). This suddenly gives way to a scurrying V1-derived epilogue [T-15] that turns spastic and closes the work with a twitchy forte “So there!” cadence.

Bringing this release to a fetching conclusion, there’s David’s Double Concerto for violin, viola and strings (2013), which he says was inspired by one of his favorite works, namely W.A. Mozart’s (1756-1791) Sinfonia Concertante for the same solo instruments (K 364, 1779). He also notes that instead of a virtuosic rivalry between the soloists, the Mozart imparts a feeling of their coming together in friendship, and that’s what he’s tried to express here.

A three-movement work, the first is a modified, sonata form “Allegro grazioso” (“Lively, but graceful”) [T-16]. Its opening statement starts with a busy, CV-like (see above) thematic nexus (BC) for the tutti [00:01] that’s picked up by the violin and viola [00:43]. Then BC undergoes a contrapuntally spiced exploration, which bridges [02:51] into a dramatic dialogue for the soloists [03:00] rather than the usual development.

Here there are manic, cadenza-like passages for both, after which a harmonically robust version of BC initiates a recapitulation [05:38]. This contains anguished remembrances of BC for everyone, and ends the movement uneventfully.

The “Lento” (“Slow”) [T-17] has a haunting tutti preface [00:01] and upward, swirling passages for the soloists [00:31] that become pensive. They transition into an avian-associated episode [03:02-04:50], where the composer’s keen ear for birdsong (see the above Symphony) is again apparent as the violin and viola imitate nightingales. Then the movement ends contemplatively with recollections of its opening material and more calls from our feathered friends.

David tells us the concluding “Presto scorrevole” (“Fast and facile”) [T-18] is based on the finale of his Ninth String Quartet (2000; not currently available on disc), which he modelled after the Chopin (1810-1849) “Funeral March” Piano Sonata’s (No. 2, B 128, 1837-9) last movement. An eerie, “rondoesque” creation, this starts with BC-reminiscent, scampering, pizzicato-spiced passages for both soloists and tutti (BS) [00:01]. These engender a related, Irish-jig-like ditty (BI) [01:13] that cavorts about with BS, bringing the work and this delectable disc of discovery to a cursory conclusion.

English violinist Sara Trickey along with violist Sarah-Jane Bradley are well paired in the Double Concert, and give a loving, yet technically accomplished account of it. Their efforts are all the more striking for the dedicated support they get from Conductor Woods and the EStgO, who also deliver a magnificent reading of the Variations.

Although the string selection recordings were also done in 2018, they took place a few months after the symphonic one and at The Priory Church, located in Great Malvern, about 50 miles north of Bristol. Yet, despite the different venues, all three project cognate sonic images in similar sounding spaces.

Characterized by pleasant highs, a lifelike midrange and clean bass, the string tone is as good as it gets on conventional discs. What’s more, the soloists, who are positioned slightly left (violin) and right (viola) of center stage, are ideally highlighted against the EStgO. In conclusion, taking these as well as the above recording into account, this Nimbus earns an “Audiophile” rating.

— Bob McQuiston, Classical Lost and Found (CLOFO.com, Y190927)