Description

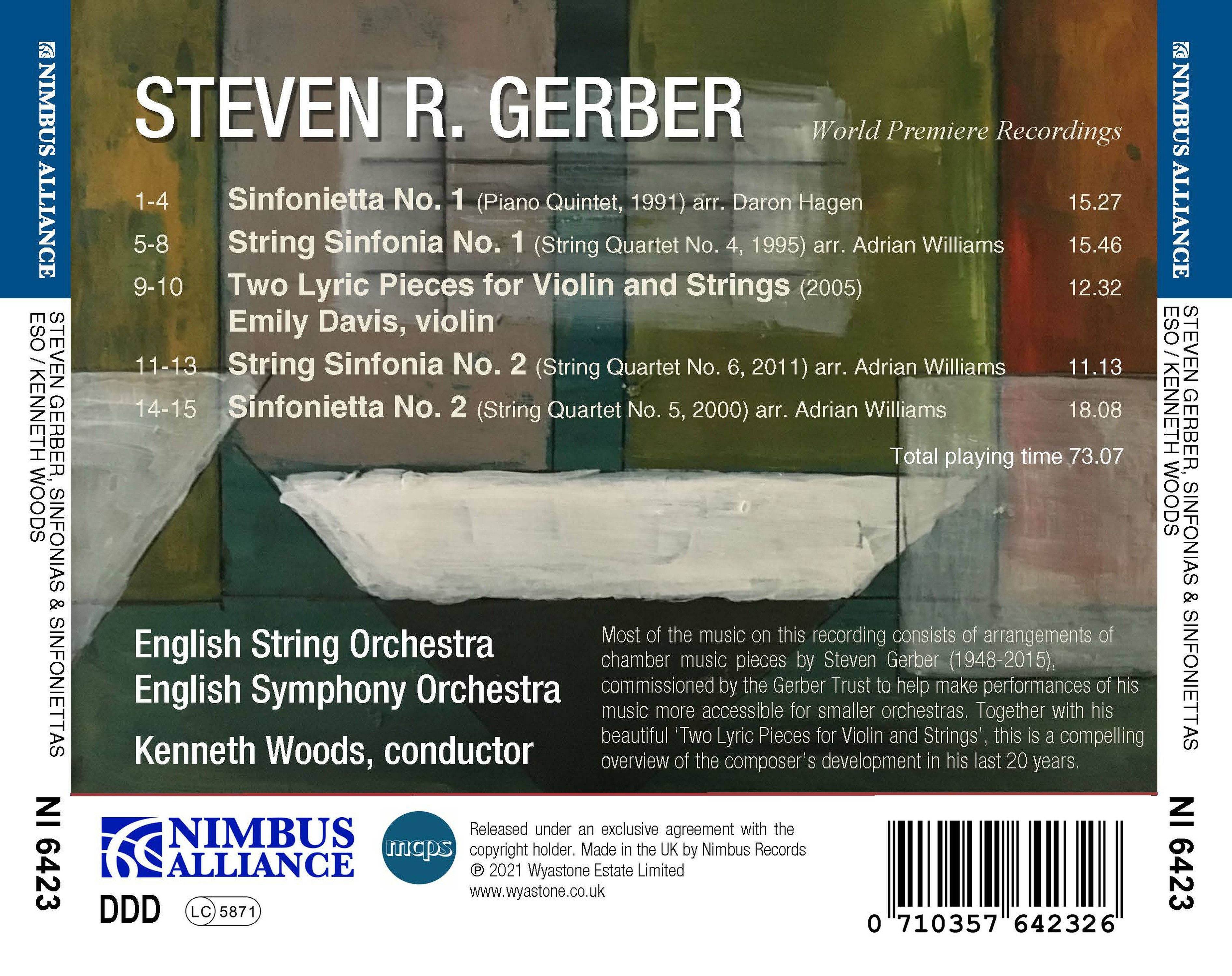

NI6423 features a collection of music composed by Steven R Gerber and offers world premiere recordings by the English String Orchestra headed by Kenneth Woods.

NI6423 features a collection of music composed by Steven R Gerber and offers world premiere recordings by the English String Orchestra headed by Kenneth Woods.

Steven R. Gerber was born in 1948 in Washington, D.C. and made his home in New York City, where he died on May 28, 2015, aged 66. He received degrees from Haverford College and from Princeton University, where he received a 4-year fellowship. His composition teachers included Robert Parris, J. K. Randall, Earl Kim, and Milton Babbitt. Most of the music on this recording consists of arrangements of chamber music pieces by Steven Gerber (1948-2015), commissioned by the Gerber Trust to help make performances of his music more accessible for chamber orchestras, smaller symphony orchestras and string orchestras.

“…a fascinating overview of Gerber’s development as a composer over most of the last 20 years of his working life.Intriguing and engaging music which..could hardly be faulted for emotional immediacy. It certainly found worthy exponents in the musicians of the ESO, directed by Woods with his customary conviction… Those coming anew to Steven R. Gerber will doubtless have responded to his unwavering sincerity.” Richard Whitehouse, Arcana.fm

Admin –

Records International

“An impressive collection of powerful works by a composer who obviously deserves to be much better known than he is. Gerber’s idiom is tonal, in a mid-20th century style with a rather astringent edge to his otherwise post-romantic harmony, and a sporadic incorporation of fairly extreme dissonance as dictated by the expressive requirements of the piece. Given the quality and expressive power of his music, the fact that it never established a foothold in the repertory seems surprising; for reasons unexplained it appears that he had at least as much success and recognition in Russia and Ukraine as in the USA. He wrote orchestral scores, but the few recordings of several of these were made more than 20 years ago. The Steven R. Gerber Trust astutely commissioned the transcriptions of four of his substantial chamber works from Daron Hagen and Adrian Williams, two composers whose own styles are remarkably attuned to Gerber’s own, and the resulting works are superb transformations into orchestral scores, Williams’ full-orchestral arrangement of Gerber’s Fifth Quartet in particular disguising its modest original forces so completely as to sound as though its symphonic argument was conceived in terms of the orchestra. Gerber was fond of variation form, and the finale of this work provides ample opportunity for vivid timbral and textural embellishment of the material. The finale of the 2nd String Sinfonia (Quartet No.6) and the Passacaglia from the Lyric Pieces (performed as originally written) also display Gerber’s skill and originality in his treatment of this form. The First Sinfonietta is the earliest original work, Gerber’s 1991 Piano Quintet, and Hagen makes of this incisive, neoclassical Stravinsky influenced work a rhythmically alert orchestral piece which also allows space for some ravishing tonal episodes of pastoral, English-sounding repose; the composer’s use of modally inflected tonality and open intervals also suggests Copland. Bartók is clearly a major influence, beginning with the “Mesto” finale of this work, and even more so in the later quartets, and Shostakovich (some association with the composer’s Russian connections here?) especially in the inexorable, menacing surge of the “Maestoso” movements of the Sinfonia No.1 (Quartet No.4) and No.2 (Quartet No.6). This latter quartet was among Gerber’s last works, and there seem to be references to the resilient resignation of late Beethoven in the piece, dedicated to the memory of the composer’s long-time companion, Dr. Norma Hynes. Emily Davis (violin), English String Orchestra, English Symphony Orchestra; Kenneth Woods.”

https://www.recordsinternational.com/cd.php?cd=11X051

Admin –

The very first measures of Gerber’s Sinfonietta No. 1 (the Piano Quintet of 1991, arranged by Daron Hagen) set out the harmonic language on this disc perfectly: acidic and intensely characterful. Sometimes the ear veers towards Bartók, at others it veers towards Stravinsky (particularly brought out by Hagen’s use of wind writing). Tuning is vital in those dissonant chords, and the English Symphony Orchestra under Kenneth Woods captures the power of each and every shard-like simultaneity. Gesturally, it strikes me as close to the opening of Stravinsky’s Symphony in Three Movements. An underlying playfulness extends to the Moderato that follows; there’s some particularly fine solo bassoon playing here. Perhaps it is in the Presto third movement that we really catch the virtuosity of the English SO. It’s a whirligig of a movement, and I do have to echo Kenneth Woods’s words of praise for the arrangement in his booklet notes: I doubt that any innocent ear could detect that this was originally a work for piano and single strings. Gerber does (deliberately) leave one aching for more. That movement is just over a minute long, leading to the nearly 8-minute Mesto—Coda finale. This is the movement with marked links to Bartók’s Sixth Quartet (which shares the same marking).

The String Sinfonia No. 1 is an arrangement by Adrian Williams of Gerber’s 1996 String Quartet No. 4. Immediately the string-only sound feels slighter, the chordal structures illuminated from within, the harmonic twists remarkably fetching. There is little sense of Stravinsky hovering here; instead, there is a dance between huge intensity and moments of wispy, half-remembered moments. If there is a ghost here it is that of Shostakovich, perhaps particularly in the Lento slow movement, or in the punctuating chords of the first (which Woods convincingly likens to the off-beats of Shostakovich’s Eighth String Quartet). It is in the third movement that one really hears the importance of the double bass to the texture: grounding, powerful in its inevitability. Gerber’s decision to end the piece with a movement that is the polar opposite of what precedes it is a masterstroke. And while in the earlier movements one might admire the English String Orchestra’s virtuosity, here it is the elusive beauty of sound coupled with the perfect realization of Gerber’s hypnotic repetitions that penetrate to the heart. Williams’s arrangement is masterly, finding huge variety of light and shade and utilizing his forces (particularly those double basses) commandingly, all the while honoring Gerner’s original.

The interview above heaps praise on the skills of violinist Emily Davis; her performances here are of the only original pieces on the disc. The Two Lyric Pieces were written in 2005 for Elena Urioste and premiered by her in Washington, DC. There are identifiably American roots here, as Woods suggests; but there is also the whimsy of the English Pastoralists hovering in the air. The “Introduction and Berceuse” first movement is expansive; the Passacaglia, a concentrated five minutes. Shadows are very much part of the soundscape, while extreme registral separation of solo violin and lower strings creates a real sense of a void that must be filled.

The String Sinfonia No. 2 is Adrian Williams’s arrangement of Gerber’s Sixth (and final) Quartet. Written in memory of the composer’s long-time partner, who passed away from cancer in 2010, there is a palpable sense of agony to the music. The first movement is also a good example of Gerber’s use of tempo intensification discussed in the interview. Woods has pointed out a similarity between a passage of alternating soft and loud chords and Beethoven’s musical “Muss es sein?” question from his late, “third period” works. Certainly, there is the feeling of Gerber railing against fate. There are some metric tricks to the central Intermezzo but the effect is decidedly more macabre than playful, and how well the English String Orchestra finds the perfect atmosphere (just as its players realized the tempo intensifications with such confidence). It is the finale that reminds us so viscerally that Gerber was so at home in the theme and variations form: It is a superbly wrought, touching movement, impeccably shaped by Woods and the English String Orchestra.

It is only right that the collection is bookended by two full symphony orchestra works, the two Sinfoniettas. The Second Sinfonietta is Adrian Williams’s arrangement of Gerber’s Fifth String Quartet of 2000. To the double woodwind and brass of Sinfonietta No. 1, Williams adds tuba, timpani, and harp, appropriately for what is Gerber’s longest string quartet. The first movement is based on the pentatonicism of Negro spirituals, whereas the second (the Theme and Variations) takes us to more chromatic regions. This finale is the movement Woods has likened to Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique, and how that is borne out in the gestural nature of Gerber’s writing and the technicolor scoring by Williams. Gerber’s final coup de théâtre is to begin the opening melody of the first movement together with the macabre second movement melody, a moment of genius.

This disc offers the perfect starting point for an appreciation of Steven R. Gerber’s gifts as a composer. Colin Clarke – Fanfare Magazine

This article originally appeared in Issue 45:5 (May/June 2022) of Fanfare Magazine.

Admin –

Steven Gerber, Sinfonias and Sinfoniettas, pairs the American composer’s Two Lyric Pieces for violin and strings with several of his chamber works as arranged for larger ensembles. All of the pieces receive world premiere recordings on this release. As conductor Kenneth Woods explains in his thoughtful and informative liner notes, the arrangements were “commissioned by the Gerber Trust to help make performances of his music more accessible for chamber orchestras, smaller symphony orchestras and string orchestras.” The works included on the Nimbus Alliance release span the years 1991–2011 and, according to Woods, “provide a fascinating overview of Gerber’s development as a composer over most of the last 20 years of his working life.” Steven R. Gerber (1948–2015), born in Washington, DC, studied composition with, among others, Milton Babbitt. Gerber enjoyed recognition not only in his native country, but in Russia and Ukraine, where he toured frequently, and had many of his works performed. On the evidence of the pieces featured in this recording, Steven Gerber’s musical voice defies easy generalization. His music does strike me as favoring introspection and melancholy. The carefree, humorous touch is rare. Gerber also demonstrates a predilection for theme and variations movements. These are quite effective both in exploring the potential of a given theme, and crafting variations in a manner generates considerable dramatic impact.

But the voice Gerber employs varies considerably from work to work. The opening Sinfonietta No. 1, an arrangement for orchestra by Daron Hagen of Gerber’s 1991 Quintet for Piano and Strings, evokes the spirit of Stravinsky’s Neoclassical works. That quality is emphasized by the pungent contributions of Hagen’s winds and brass. There are also suggestions of Bartók in the work’s Mesto finale that includes an anguished cluster from the high woodwinds and strings. By contrast, the String Sinfonia No. 1 (Adrian Williams’s arrangement of Gerber’s 1995 String Quartet No. 4) advances in broad, lyrical strokes. Gerber composed his Two Lyric Pieces for violin and strings (2005) for Elena Urioste. Here, Gerber’s peaceful and soaring music for the solo violin suggests the influence of Vaughan Williams. Both the String Sinfonia No. 2 and Sinfonietta No. 2 conclude with theme and variations movements. The former is Williams’s arrangement of Gerber’s 2011 String Quartet No. 6. The latter is another Williams arrangement, this time for large orchestra, of Gerber’s 2000 String Quartet No. 5. The finale of the String Sinfonia No. 2 is contemplative, with the ultimate variation, titled “Requiescat in Pace” by the composer, providing the serene conclusion. By contrast, the Sinfonietta No. 2 ends with a movement of which Woods suggests that “One might describe it as a 21st Century descendant of the last movement of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique.” Both the central theme’s melodic contour and imposing quality recall Berlioz’s quotation of the Dies irae in the last movement of the Fantastic Symphony. And like Berlioz, Gerber exploits the melody’s potential for grotesquerie, redoubled by Williams’s colorful orchestration. It makes a powerful impact, indeed.

Conductor Kenneth Woods leads the English String Orchestra and English Symphony Orchestra in propulsive, colorful, and nuanced accounts of the various works. The ensembles play with admirable precision and tonal richness. Emily Davis is a radiant soloist in the Two Lyric Pieces. The recording, made in Wyastone Concert Hall, Monmouth, has a sense of resonance and space I associate with many Nimbus ventures, but without loss of detail. This release offers much to relish and ponder. Recommended. Ken Meltzer

This article originally appeared in Issue 45:5 (May/June 2022) of Fanfare Magazine.

Admin –

American composers of Steven Gerber’s generation—he was born in Washington, DC in 1948—came of age when Schoenbergian atonality and serialism were dominant, with only the faintest signs that their reign was about to end. Gerber began as an atonal composer from his graduate studies at Princeton with Earl Kim and Milton Babbitt, and he pursued the style until the watershed decade of the 1980s. Audience enthusiasm for Minimalism toppled atonality and breathed new life into traditional diatonic harmony (a simplification, since tonal music was always being written, however much it was disdained by advanced composers). Faced with which camp to align himself with, Gerber was more successful than most at refashioning his idiom, starting in 1981, and he found his new tonal music being compared with Copland and Roy Harris, a shock for anyone with this background—back to the future with a vengeance.

The risk of sounding derivative and retrograde was real, but let me return to that later. Gerber was fortunate to strike a vein of popular acceptance, and this new album, which consists of world premieres, is the latest among a handful since his death in 2015 at age 66. With the exception of the Two Lyric Pieces for violin and strings, these are arrangements commissioned by the Gerber Trust of chamber music scores, now expanded on a larger scale either for full orchestra or string orchestra. The fact that the originals include three string quartets (Nos. 4, 5, and 6) is a reminder of the chamber symphonies that were made from quartets by Shostakovich and Mieczys?aw Weinberg. In fact, Gerber’s music enjoyed considerable popularity in Russia, where string orchestras are plentiful; his Wikipedia entry claims that Gerber’s music “has been played in the former Soviet Union perhaps more widely than that of any other American composer.”

I don’t know how that claim could be verified, but without a doubt Gerber had a strong foothold in Russia, as evidenced by performances led by Mikhail Pletnev with the Russian National Orchestra and Vladimir Ashkenazy with the San Francisco Symphony. A number of works were composed for Russian soloists, the most prestigious being the renowned violist Yuri Bashmet. In short, a composer I had never encountered before—I think this holds true for many Fanfare readers as well—attained prominence outside my field of vision.

The quality of these five works justifies Gerber’s success. The four Sinfonias and Sinfoniettas are brief—the longest is Sinfonietta No. 2 at 18 minutes—and the movements are miniatures. Each is distinctive, strikingly colorful, and ingenious, proving (if it needed to be proved) that tonal classical music is far from exhausted. I wish that these posthumous arrangements had titles less generic than Sinfonia and Sinfonietta, because Gerber was in touch with human emotion, and when he writes sad music, as in the finale of Sinfonia No. 1 (which is marked Mesto, the same as all four movements of Bartók’s String Quartet No. 6), there is no mistaking the mood or intention, whether a movement is a racing Perpetuo mobile, a lullaby, or filled with angry, stabbing chords.

Clearly Gerber found his voice, fulfilling the adage, “Inside every fat man there’s a thin one trying to get out,” in this case “Inside every atonal composer there’s a tonal one trying to get out.” Believe that as you will, it cannot be denied that Gerber found the right idiom, but did he find his own distinctive voice? To judge by these chamber work arrangements, his closest counterpart might be Weinberg, whose prolific output displayed every musical virtue but originality. Among the works I’ve heard, I’d make an exception of the sorrowing and powerful Symphony No. 21, and Weinberg at his most imitative was either an echo of Shostakovich or a popularizer of folk material, neither of which is relevant to Gerber. But it is very hard to say of a piece, “This has to be Weinberg,” and just as hard with Gerber.

You hear flashes of recognition here and there that sound briefly like Copland or Bartók or even Bernard Herrmann, and almost entirely Gerber’s harmonies don’t extend beyond Bartók and Stravinsky in their prime. What matters is that he makes ingenious use of their idioms without falling into slavish imitation. But the issue is abstract when you are listening to these very attractive, accessible arrangements by Daron Hagen (Sinfonietta No. 1) and Adrian Williams (Sinfonietta No. 2 and the two Sinfonias for String Orchestra), beautifully played by the two English orchestras and conducted expertly and sympathetically by Kenneth Woods. It’s impossible to generalize about 15 separate movements that range so widely in style. Woods provided the informative program notes that describe each work, and the qualities he mentions, such as “American” open chords, pentatonic melodies, and long-breathed lyrical lines indicate how strongly the ear is drawn to the 1930s.

Yet I’d say that Gerber escapes the risk of pastiche, and even though the gently pastoral/elegiac Two Lyric Pieces, expressively performed by violin soloist Emily Davis, could have been stamped out by a Prairie School composer during the Great Depression, so much is Gerber’s own that my attention never wandered. The standout on the program is the colorfully orchestrated Sinfonietta No. 1, arranged from the Piano Quinet of 1991, where every gesture, mood, and melody is impressive. In sum, anyone with an interest in Americana from Ives through Barber, Copland, and beyond will find much rewarding music here. Huntley Dent

This article originally appeared in Issue 45:5 (May/June 2022) of Fanfare Magazine.

Admin –

Written by Richard Whitehouse

The English Symphony Orchestra’s online (hopefully not too much longer!) season continued tonight with this portrait of American composer Steven R. Gerber (1948-2015). Little heard in the UK (but extensively in Russia during the immediate post-Soviet era), his output follows a not unusual trajectory for someone of his generation – that from serialism to a rapprochement with tonality, though his evident success over these nominally opposing aesthetics is far rarer and confirms a creative zeal as was underlined by the works featured in this ESO programme.

Although he essayed a sizable number of orchestral works (including two symphonies), those pieces heard here were arrangements of chamber pieces. Not that they were at all unidiomatic or lacking impact – witness that of his Piano Quintet by Daron Hagen as the First Sinfonietta, whose five movements evolve in opposition between a pungent incisiveness and an emotional plangency which finds its culmination in the powerfully sustained fourth movement. Kenneth Woods secured a trenchant response from an ESO likely at or near its socially distanced limit.

The other arrangements were all undertaken by Adrian Williams, himself a notable composer of whom the ESO will be playing more in due course. Derived from Gerber’s Fourth Quartet, the First String Sinfonietta is notable for the comparable intensity of its central movements – a Lento then a Maestoso which might have functioned as a finale had not the composer opted, effectively as it turned out, to let such emotions subside over the curse of a brief yet affecting Postlude. It was astute programming to follow this with the Two Lyric Pieces for violin and strings, the only item played in its original guise and one whose mingling of wistfulness and eloquence finds the composer at his most approachable; not least when Emily Davis rendered the solo part with such fluency and poise. These pieces could yet enjoy a widespread success.

As derived from Gerber’s Sixth Quartet, the Second String Sinfonia appears to be among his more quizzical works – the angular while not a little ambivalent opening movement making way for a quizzical Intermezzo, then a closing set of variations that does not so much reach a climax as wind down into an uncertain repose. A more elaborate and methodical take on the Variations template is pursued by the second and final movement of Gerber’s Fifth Quartet, here arranged as the Second Sinfonietta which again has recourse to a fuller instrumentation and more charged expression. Notably the opening Fantasy, whose stark contrasts of mood make for a disjunctive overall trajectory as is subsequently countered, if not wholly resolved, through a steady and always inevitable build-up of the finale towards its forceful apotheosis.

Intriguing and engaging music which, if tending to an unrelieved earnestness, could hardly be faulted for emotional immediacy. It certainly found worthy exponents in the musicians of the ESO, directed by Woods with his customary conviction, while hopefully the tendency of the sound to distort in louder or more fully scored passages – what used to be termed ‘flutter’ in recorded parlance – was a factor of the online broadcast and not of the actual session. Those coming anew to Steven R. Gerber will doubtless have responded to his unwavering sincerity.

You can watch the concert on the English Symphony Orchestra website here

For more information on the English Symphony Orchestra you can visit their website here For more on Steven R. Gerber, visit his website

https://arcana.fm/2021/03/03/eso-woods-steven-gerber/