Description

Links to this record on all major streaming sites here

Critical Responses (complete reviews in the ‘reviews’ tab)

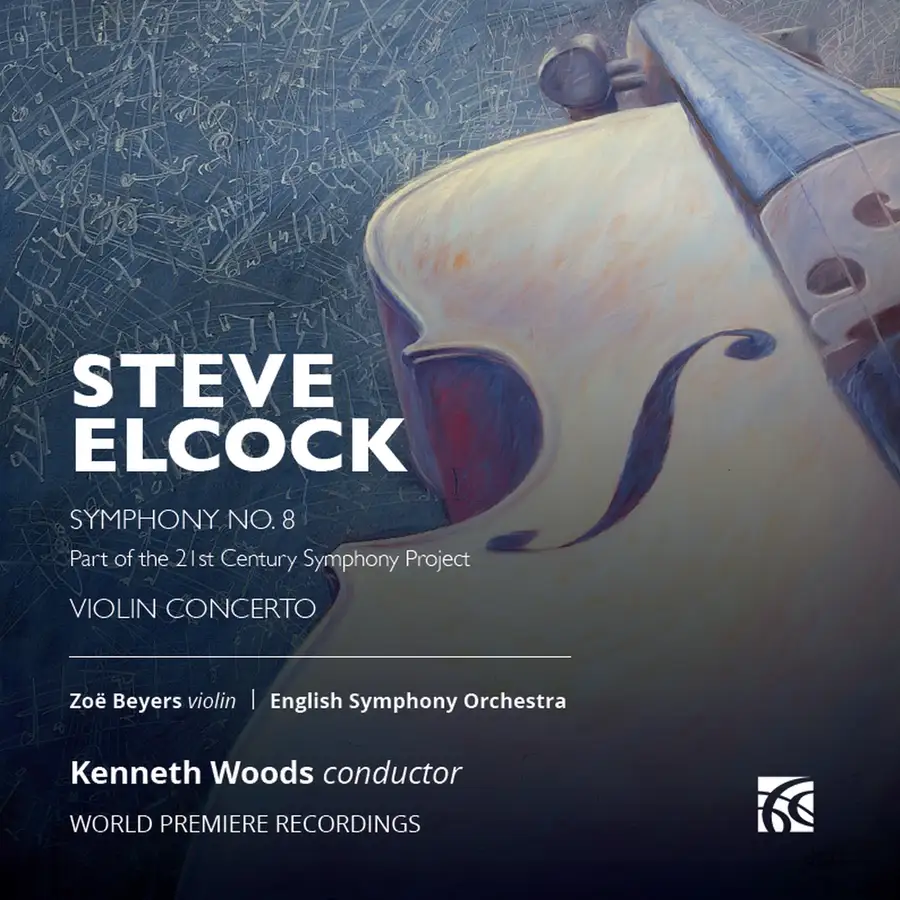

Critic Jean-Yves Duperron adds his voice to the chorus of enthusiastic responses to the visceral and compelling music of Steve Elcock Composer.

” If you enjoy classical music in general, with a preference for symphonic writing, this living composer ticks all the boxes when it comes to harmonic integrity, orchestration colors and textures, emotive power and structural stability… Kenneth Woods, conductor captures every expressive nuance within this work. And if anything, Steve Elcock’s music is powerfully expressive… the Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 13 is a beautifully languorous inner slow movement which sees the violin soar into the stratosphere, bookended by two outer shorter movements brimming with energy, playfulness and mischief, especially in the opening Allegro vivo. Violinist Zoë Beyers, who has been the concertmaster of the English Symphony Orchestra since 2017, delivers a finely crafted, utterly expressive interpretation that well defines the work’s contrasting elements.”

More much-appreciated recognition for our new record of music by Steve Elcock Composer on Nimbus Records, this time from the estimable Richard Whitehouse at Arcana.fm. Stream or download the whole thing here:

“The concerto is a tough challenge for any soloist and one Zoë Beyers meets with assurance – its close-knit interplay of soloist and orchestra brought off with admirable precision, and its occasional modal subtleties rendered as enrichments of the tonal trajectory. Elcock has been fortunate in his recorded exponents, and this new ESO release is emphatically no exception… For now, this latest release warrants the strongest of recommendations.

It’s so gratifying to see such a positive respone to our most recent Nimbus Records recording of the music of Steve Elcock Composer, featuring violinist Zoë Beyers and Kenneth Woods, conductor. This review, from the new issue of Gramophone, is from critic Guy Rickards.

“A thoroughly gripping, involving album, urgently recommended.”

Another exciting review for our new Nimbus Records recording of the music of Steve Elcock Composer with violinist Zoë Beyers and Kenneth Woods, conductor from Remy Franck at Pizzicato in Luxembourg. You can listen on all the major streaming platforms here:

“…Elcock writes more accessibly than Pettersson and more emotionally and communicatively than Simpson…Steve Elcock’s 8th Symphony is presented in one movement in just under 25 minutes. The instrumentation is designed for a classical setting. An expansive, calm opening, which introduces all the motifs right at the beginning, transitions into a desperate mood in the face of an impending catastrophe. “

“The South African violinist Zoë Beyers, who lives in England, performs the solo part with verve and impeccable quality. She is able to hold her own effortlessly against the orchestra and shape her voice expressively.”

“Together with Kenneth Woods, the English Symphony Orchestra presents this recording in its series of 21st century symphonies. They present themselves as an ensemble well versed in the modern musical language, which is also ideally suited to this task.”

We’re incredibly excited about our new Nimbus Records recording featuring the music of Steve Elcock Composer with violinist Zoe Beyers and Kenneth Woods, conductor. Both Steve’s music and Zoe’s fiddle playing made a HUGE impact with audiences at the Elgar Festival earlier this month.

Released on 7 June, Classical Music Daily wrote of it:

“I do believe Steve Elcock will be one of those composers that will be talked about and listened to for some time. This recording of two very fine works features a superb violinist Zoë Beyers and a very good orchestra indeed – the English Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Kenneth Woods, who obviously understands this composer and his works. This is a recording not to be missed. I am pleased to see a well written and informative booklet accompanying this disc.”

Admin –

Read the Original Here:

https://lilijanamaticevska.wordpress.com/2024/06/12/review-steve-elcock-symphony-no-8-violin-concerto/

We start with an immediate whirlwind of disparate ideas, immediately flung into a fast paced string of unresolved tensions, small melodic fragments aching to form an identity for themselves. It’s as if the music begins in the middle of a development section, and only through the incessant repetition of motifs do we begin to understand that this music is not trying to make a welcome introduction in the manner of any other Romantic-era-inspired concerto. While staying very well within a neoromantic idiom, with an approach to orchestral and virtuosic violin writing that never strays outside of what we can expect in 19th century music, it’s the wild, untamed motifs that burst this style at the seams often in an uncompromising way, suggesting something undoubtedly not of the Romantic era in the slightest. One wishes that the orchestra plays into this idea more, to truly appreciate the unsettled angst and grit of Elcock’s eschewing of a more traditional phrasal structure in favour of obstinately repetitive, fragmentary diatonicism. And once we’ve established this is the nature of the beast, the following two movements only subvert this to provide a flowing, melodic middle movement followed by a serious, multifaceted—and more chromatic—passacaglia. The third is my personal favourite movement and is over all too soon. The consistency between all three wide ranging movements however, is the clarity of motif and repeated material.

The real highlight of the album is Elcock’s symphony no. 8 which begins as a series of motifs layered over one another in the string section from lowest to highest. It’s a simple but effective way of introducing the first important material of any work. The music stays put in a sombre place before finally being nudged forward by a solo cello. The orchestra responds in groups of violins, trumpets, woodwinds, almost attempting to answer the cellist’s remark until a new motific identity is formed out of its uncertainty and tense atmosphere. Elcock plays to the perceived heights and depths of register extraordinarily effectively here, with a terrific sense of pace when focussing on each region of higher or lower sounds. The repetitive, motific style we know Elcock for allows for a slow walk between each of these timbral and registral regions, hearing them from different perspectives as the main motific material (or treatment thereof) changes.

This is a very Sibelian approach to symphonic form. For any listener familiar with the development of the ‘symphony’ as a genre into the 20th century and beyond, Sibelius’s 7th comes to mind as the first major single movement symphony that eventually was titled a symphony, or even the larger scale works by Allan Petterssen. To title something a ‘symphony’ today would certainly have implications around how a composer chooses to engage with western classical music histories and what historical influences, lineage, family of musical works we may identify it with. Although at face value we can’t assume this is an influence on Elcock’s music, its existence is culturally significant enough for us to ponder on the similarities and differences—the slow rise from the depths, the gradual growth and subtle changes from one motif to the next that ultimately bring us from one larger subsection to the next. In particular it’s the use of solo strings to mark certain points in Elcock’s 8th and some of the more static, slow paced sections that allow the audience to sit with a particular remarkable sound like repetitive ricocheting bows in the background before one textural layer, such as an ostinato between two notes alternating a semitone apart, forms a consistent link to a new section.

The music, although often quiet, slow and restraint, has a certain clarity and consistency to it, markedly different from the opening of the violin concerto which is almost too fast to process at the speed we are introduced to different timbral, textural and motific ideas. The true challenge in performance would be how exposed many of the textures are and the English Symphony Orchestra treads carefully and sensitively along this tightly composed symphony where every note counts.

Uncategorized

Published by

Lilijana Mati?evska

Admin –

Original:

https://arcana.fm/2024/05/18/elcock-beyers-eso-woods/

Zoë Beyers (violin), English Symphony Orchestra / Kenneth Woods

Elcock

Violin Concerto Op.13 (1996-2003, rev. 2020)

Symphony no.8 Op.37 (1981/2021)

Nimbus NI6446 [56’24’’]

Producer and Engineer Phil Rowlands

Recorded 28 July 2021 (Symphony), 26 May 2022 (Violin Concerto) at Wyastone Concert Hall, Monmouth

Reviewed by Richard Whitehouse

What’s the story?

The English Symphony Orchestra and Kenneth Woods add to their much lauded 21st Century Symphony Project with this release devoted to Steve Elcock (b.1957), juxtaposing two major works which confirm his standing among the leading European symphonists of his generation.

What’s the music like?

Both works heard here only gradually assumed their definitive form. Composed at stages over almost a decade, the Violin Concerto marks something of a transition between less ambitious pieces for local musicians and those symphonic works which have come to dominate Elcock’s output. Its initial Allegro vivo is a tensile sonata design whose rhythmic energy is maintained throughout, with enough expressive leeway for its second theme to assume greater emotional emphasis in the reprise. There follows a Molto tranquillo whose haunting main theme, at first unfolded by the soloist over undulating upper strings in a texture pervaded by change-ringing techniques, is a potent inspiration. A pavane-like idea soon comes into focus while the closing stage, reaching an eloquent plateau before it evanesces into silence, stays long in the memory. The short but eventful finale is a Passacaglia whose theme (audibly related to previous ideas) accelerates across five variations from Andante to Presto, before culminating in a heightened cadenza-like passage on violin and timpani then a peremptory yet decisive orchestral pay-off.

The Eighth Symphony has its antecedents even further back, having begun as a string quartet in the early 1980s, though it continues those processes of evolution and integration central to the seven such works which precede it. It reflects the impact of the Sixth Symphony by Allan Pettersson (still awaiting its UK premiere after 58 years), but whereas that epic work centres on fateful arrival, Elcock’s single movement is more about striving towards a destination that remains tantalizingly beyond reach. Numerous pithy motifs are stated in the formative stages, as the music alternates between relative stasis and dynamism before being thrown into relief by the emergence (just before the mid-point) of a trumpet melody that goes on to determine the course of this piece as it builds inexorably towards a sustained climax then subsides into a searching postlude. Overt resolution may have been eschewed, yet the overriding sense of cohesion and inevitability duly outweighs that mood described by the composer as ‘‘one of desperation in the teeth of impending catastrophe’’ which, in itself, becomes an affirmation.

Does it all work?

Certainly, given both works receive well prepared and finely realized performances – notable for the way Elcock’s demanding yet idiomatic string writing is realized with real conviction. The concerto is a tough challenge for any soloist and one Zoë Beyers meets with assurance – its close-knit interplay of soloist and orchestra brought off with admirable precision, and its occasional modal subtleties rendered as enrichments of the tonal trajectory. Elcock has been fortunate in his recorded exponents, and this new ESO release is emphatically no exception.

Is it recommended?

Indeed, and good to hear that, as the ESO’s current John McCabe Composer-in-Association, Elcock will feature on a follow-up issue of his pieces Wreck and Concerto Grosso, along with the recent Fermeture. For now, this latest release warrants the strongest of recommendations.

Listen & Buy

You can listen to sample tracks and purchase on the Naxos Direct website. For further information on the artists, click on the names for more on Zoë Beyers, the English Symphony Orchestra and their conductor Kenneth Woods. Click on the name for more on composer Steve Elcock

Published post no.2,182 – Saturday 18 May 2024

Admin –

http://www.classicalmusicsentinel.com/KEEP/elcock8.html

STEVE ELCOCK – Symphony No. 8 – Violin Concerto – English Symphony Orchestra – Zoë Beyers (Violin) – Kenneth Woods (Conductor) – 0710357644627 – Released: June 2024 – Nimbus Alliance NI6446

Violin Concerto (2006)

Symphony No. 8, Op. 37 (1981/2021)

Ever since I heard this composer’s Symphony No. 3 back in 2017, I have, like a sentinel guard, been on the lookout for any and all subsequent recordings of his music. I’ve since also reviewed his Symphony No. 5, Symphonies Nos. 6 & 7 and his String Quartets, all of which, like this release, are world premiere recordings. I had mentioned this before and it bears pointing out again: “this self-taught composer doesn’t try to impose on the listener a new cacophonous language, or paint an alien sonic landscape, but rather adds his own original and highly brilliant brush strokes to a canvas framed by historical convention.”

Like most of the best late 19th and 20th century composers before him, he in his own subtle way, drops a musical seed into the listener’s fertile psyche which germinates along the way like signposts down a winding road. Often unaware of the motivic nascence, the listener will recognize something familiar along the way that will act as a beacon lighting the way forward in the darkness. For a self-taught composer, it’s rather startling as to how well Steve Elcock (b. 1957) achieves this. Many years ago I read a book titled “The Psychology of Music” which explained amongst other things that a crucial element in music is a certain degree of repetition. Mind you, not outright constant duplication, or repetition ad nauseum like minimalism, but recurring motivic and thematic ideas that move the music along to its logical resolution. Too many modern or living composers meander all over the place which in the end, leaves the listener stranded as if lost at sea with no ports of call along the way.

The Symphony No. 8 was recently commissioned by the English Symphony Orchestra and first performed during their Three Choirs Festival in 2021. Although completed in 2021, it is based on a String Quartet from back in 1981 discarded by Elcock. From that perspective, it could be seen as an 8th symphony conceived prior to all of his other seven symphonies, but it certainly belongs in its numerical position within the canon. In its first arrangement for string orchestra, Elcock titled the work Dark Tidings: Sinfonietta for Strings, but in its final orchestration and present form that title was dropped. It certainly is a dark and foreboding work, especially within its opening pages where it’s very redolent of some of Shostakovich’s bleakest slow movements. A single-movement structure just over 23 minutes in duration it arcs exceptionally well from its ominous introduction, to fierce bouts of despair at its core, ending the way it started in enigmatic darkness. Conductor Kenneth Woods, who has also released a gripping account of the Symphony No. 4 by Philip Sawyers, captures every expressive nuance within this work. And if anything, Steve Elcock’s music is powerfully expressive. A characteristic sorely lacking in 21st century orchestral music.

In contrast, the Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 13 is a beautifully languorous inner slow movement which sees the violin soar into the stratosphere, bookended by two outer shorter movements brimming with energy, playfulness and mischief, especially in the opening Allegro vivo. Violinist Zoë Beyers, who has been the concertmaster of the English Symphony Orchestra since 2017, delivers a finely crafted, utterly expressive interpretation that well defines the work’s contrasting elements.

The more I discover and experience the music of Steve Elcock, the more I feel the need to recommend it to anyone who happens to read this review. If you enjoy classical music in general, with a preference for symphonic writing, this living composer ticks all the boxes when it comes to harmonic integrity, orchestration colors and textures, emotive power and structural stability. For a self-taught composer, he could very well be the poster boy for ‘dedication trumps academia’.

Jean-Yves Duperron – June 2024

Admin –

From Gramophone Magazine:

https://www.gramophone.co.uk/review/elcock-symphony-no-8-violin-concerto-zoe-beyers

The fifth release in Kenneth Woods and the English Symphony Orchestra’s groundbreaking ‘21st Century Symphony Project’ focuses on Steve Elcock (b1957), composer-in?residence at this year’s Elgar Festival, and features the eighth of his 10 symphonies and his Violin Concerto. The concerto was begun around 1996, and its substantial opening Allegro vivo is energetic and Classical in outlook. Its lovely central Molto tranquillo (the longest movement, added in 2003) is more reflective, wistful at times, and is beautifully played by Zoë Beyers. The briefer final Passacaglia, added in 2006 for a prospective performance that did not materialise, is electrifying. Following a revision in 2020, the present performers gave the premiere in Bromsgrove in May 2022; this recording was made the day beforehand.

Elcock’s Eighth Symphony was premiered the previous July as part of the Three Choirs Festival and recorded shortly after. The composer writes in the booklet that following its two weighty predecessors (issued by Toccata Classics), he wanted to ‘write a smaller-scale piece’, and turned to a juvenile string quartet from 1981 to see what could be reworked. In the event, he produced a taut and dramatic single movement that is in no sense a lighter piece of relaxation in his output (though, as he relates, he required some convincing by his peers of its symphonic status). No 8 stays for the most part in the expressively dark world, rooted in the northern European symphonism where his best music resides, powerful, dramatic and compelling attention, and does not betray its early origins; its serener though ultimately unresolved close may be among the most ‘English’ music he has penned. The performance by the modest forces of the English Symphony Orchestra is exemplary, and they create a ‘big sound’, as one finds in (for example) Robert Simpson’s Second and Seventh, also scored for a Beethovenian ensemble. A thoroughly gripping, involving album, urgently recommended.

– Guy Rickards

Admin –

From Classical Music Daily

https://www.classicalmusicdaily.com/2024/05/elcock.htm

Originality and Freshness

GEOFF PEARCE is impressed by Steve Elcock’s Violin Concerto and Eighth Symphony

‘… well-balanced and quite beautiful …’

I do not think that I have heard anything by Steve Elcock (born 1957) before. This is my loss, because he is regarded as one of the UK’s foremost composers, even though this has only recently come about. Whilst he is a self-taught composer, this is not evident in these two works, and his output is quite substantial including ten symphonies to date. If the two works presented on this release are any indication to the depth and quality of his work, then he will be a composer well remembered.

The Violin Concerto, Op 13, is in three movements and was started in 1996. There was a long break before the composer worked on the last movement in 2006. It was not until 2022 that the work was premiered – with the same forces as on this recording.

The first movement is fast and energetic and the soloist enters almost from the beginning. There is an originality and freshness in this movement. While there is an intensity and drive, it is not at all grim and there are moments where the music relaxes so one does not feel overwhelmed. This is obviously modern music, but it is definitely very listenable. The composer has a firm grasp of orchestration and the forces gathered give their all to deliver a fine result.

Listen — Steve Elcock: Allegro vivo (Violin Concerto No 1)

(NI 6446 track 1, 9:33-10:22) ? 2024 Wyastone Estate Ltd :

The second movement contrasts the first movement. It is slow and reflective for the most part. The composer uses a ‘change-ringing technique’ to get the effect of distant bells in the strings, against which the soloist thoughtfully sings above. The effect is quite glorious and beautiful, and the climax of the work is filled with joy, before the subdued nature of the opening of the movement reasserts itself.

Listen — Steve Elcock: Molto tranquillo (Violin Concerto No 1)

(NI 6446 track 2, 8:36-9:18) ? 2024 Wyastone Estate Ltd :

The final movement is a passacaglia and is the shortest of the movements. It starts at an andante pace but slowly accelerates so that by the end of the work, the tempo is presto. The work ends in a statement of the main theme played by the timpani and soloist in a duet which creates a thrilling ending to this well-balanced and quite beautiful concerto. I enjoyed this work very much.

Listen — Steve Elcock: Passacaglia. (Violin Concerto No 1)

(NI 6446 track 3, 5:57-6:40) ? 2024 Wyastone Estate Ltd :

The other work on this recording is the Eighth Symphony, Op 37. It began as a string quartet, in 1981, then was further developed as a string piece and then, because of urging by the conductor on this recording, developed into a full symphony. It is in one movement of about twenty-three minutes in length, but contains a lot of contrast. I have read that Elcock was influenced a lot by a Swedish composer Allan Pettersson. I am very fond of Pettersson’s works, and his symphonies are often structured in one movement that grows out of small germ cells. This work also does the same thing. The symphony is powerful and almost somewhat desperate and frantic at times. This may be reading too much into it, but given the troubled times we are now experiencing and the trepidation that many of us feel, this work speaks to me. The Symphony ends quietly on a rather sorrowful note.

Listen — Steve Elcock: Symphony No 8

(NI 6446 track 4, 19:00-19:57) ? 2024 Wyastone Estate Ltd :

I do believe Steve Elcock will be one of those composers that will be talked about and listened to for some time. This recording of two very fine works features a superb violinist Zoë Beyers and a very good orchestra indeed – the English Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Kenneth Woods, who obviously understands this composer and his works. This is a recording not to be missed. I am pleased to see a well written and informative booklet accompanying this disc.

Copyright © 26 May 2024 Geoff Pearce,

Sydney, Australia

Admin –

https://www.britishmusicsociety.co.uk/2024/06/steve-elcock-violin-concerto-symphony-no-8/

Zoe Beyers violin

English Symphony Orchestra

Kenneth Woods Conductor

NIMBUS ALLIANCE NI6446

Composer Steve Elcock is living proof that we should never give up hope. As he outlines on his website, he wrote music with seemingly no hope of it being performed, but with computer technology, was able to ‘mock up’ his orchestral music into satisfactory ‘demos’.

In 2013 his work came to the attention of Martin Anderson, director of Toccata Classics, and recordings and performances he could only have dreamed of came about. This is all to the good for we listeners because his music is of extraordinary quality.

The Violin Concerto was written over a ten-year period, appearing as a wonderfully satisfying three movement work in the classical tradition. The opening is punchy and dramatic with much athletic writing for soloist, ESO leader Zoe Beyers. It is hard to believe it was originally conceived for an amateur orchestra.

The slow movement is based on change ringing bell technique. The overlapping violins and violas initially provide a shimmering background to the solo violin’s yearning melody. It is beautifully constructed and builds with an almost Sibelian tension to a climax in D major before disappearing.

The finale could have been a cerebral passacaglia, but such is the composer’s ingenuity that the form disappears into the music. Over its six minutes it builds from slow to fast and ends on a high, guaranteed to have the audience on its feet. There is much wonderfully idiomatic writing for the violin, and the orchestration is so transparent that there is no danger of her being overshadowed.

Symphony no 8 had an even longer gestation period beginning as a string quartet in 1981. Decades later, on revisiting it, the composer arranged it for strings, naming it a sinfonietta. Kenneth Woods then asked for a symphony of classical orchestra size for the 2021 Three Choirs Festival.

40 years on, with the addition of wind, brass and timpani, the final form was reached. It sounds organically constructed in one movement of 25 minutes, but with many seamless tempo changes. The brooding opening moves into a breathless scherzo-like section with some wonderful scurrying writing for the wind, before winding down to a quite ending, tinged with tragedy. It is a tremendously satisfying work that, without having a programme, seems to take us on a journey.

I have not heard any of Mr Elcock’s music before, but I shall certainly be looking out for more. This is a composer of real significance, writing music, tuneful, brilliantly orchestrated and communicative. It is exactly the type of work that sadly disappeared from concert halls in the 60s and 70s, and which we need more than ever now. The composer could not wish for better advocates than the performers and engineers assembled here.

Review by Paul RW Jackson

Admin –

Pizzicato Magazine, Luxembourg. Original:

https://www.pizzicato.lu/der-autodidaktisch-geschulte-steve-elcock/

First recordings introduce the English composer Steve Elcock. A self-taught composer, he found his way after becoming acquainted with the music of composer Allan Pettersson. He also displays the relentlessness of a Robert Simpson in his works. Yet Elcock writes more accessibly than Pettersson and more emotionally and communicatively than Simpson.

Steve Elcock’s 8th Symphony is presented in one movement in just under 25 minutes. The instrumentation is designed for a classical setting. An expansive, calm opening, which introduces all the motifs right at the beginning, transitions into a desperate mood in the face of an impending catastrophe. The consolation of the calm final bars does not materialize, as the hoped-for C major does not materialize. The music fades into silence between E flat and E major.

The first movement of the Violin Concerto would pass for a hidden object painting. A talkative, lively, virtuoso violin part seeks its place in the orchestra, which is tirelessly active in countless facets. The second theme offers a different coloration of a lighter nature, which is also accompanied by the penetrating grumbling of the violas. The second movement expands calmly. The violin intones cantilenas that can be perceived as bells ringing in the valley. The third movement is more orderly, so to speak, although not calm, in comparison to the first. This short finale in the form of a passacaglia, which gradually rises from an andante to a presto, culminates in the theme that the solo violin and timpani develop as a duo.

The South African violinist Zoë Beyers, who lives in England, performs the solo part with verve and impeccable quality. She is able to hold her own effortlessly against the orchestra and shape her voice expressively.

Together with Kenneth Woods, the English Symphony Orchestra presents this recording in its series of 21st century symphonies. They present themselves as an ensemble well versed in the modern musical language, which is also ideally suited to this task.

Admin –

Interlude HK, Maureen Buja

Original here:

https://interlude.hk/the-new-and-the-old-steve-elcocks-violin-concerto-and-symphony-no-8/

The New and the Old

Steve Elcock’s Violin Concerto and Symphony No. 8

by Maureen Buja May 27th, 2024

In a new recording coming from Nimbus, South African violinist Zoë Beyers, with the English Symphony Orchestra, takes on English composer Steve Elcock (b. 1957) and his 2006 Violin Concerto. Elcock is quite a discovery. Self-trained as a composer, he has worked for the last 50 years in France in language services, with composing as a side hobby. Recordings of his orchestral music and chamber music have been released since 2017 and quickly came to the attention of the world, with his Orchestral Music, Vol. 1, containing his Symphony No. 3, becoming CD of the Week on BBC Radio 3.

For this world premiere recording, the composer discusses this work, which he began in 1996. It consisted solely of one movement and was for strings alone. The slow movement eventually followed, and the final movement appeared in 2006.

The first movement is one of pure energy, and the composer says he was trying to return to an ideal of classical momentum that he felt had been lost from the Romantic period onward. Even when the expansive second theme appears, the violas ‘niggle’ it from below, driving it forward.

Steve Elcock: Violin Concerto – I. Allegro

The second movement takes its inspiration from most English musical genres, change-ringing in bells. The sound evokes the idea of slowly changing bells ringing across a valley, with the violin seeming to skate above. In the development section, the bell-like sound takes on an uncharacteristic, dotted rhythm and rises to a radiant climax. The movement ends, fading away as the bells cease to sound.

The finale, a passacaglia, is, at the same time a gradual accelerando, moving from Andante to ever faster, carefully laid out as: Passacaglia. Andante—Moderato—Più allegro—Allegro vivace—Subito presto—A tempo, minacciando—Allegro molto—Adagio—Più adagio—Ancora meno mosso. The gradual winding up of the tempo brings us back to the energetic idea of the opening movement.

The recording closes with Elcock’s Symphony No. 8, which, although originally started in 1981, is based on a string quartet he’d written in 1981. His original title, Dark Tidings: Sinfonietta for Strings, was dismissed by Martin Anderson, Founder and Director of Toccata Classics, as being unworthy of a work that was clearly a symphony.

When Kenneth Woods, conductor on this recording, contacted Elcock for a work to contribute to his 21st Century Symphony Project, which needed to be for a ‘Beethoven Seven’-sized orchestra (2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets in A, 2 bassoons, 2 horns in A (E and D in the inner movements), 2 trumpets in D, timpani, and strings). Woods also advocated for the title of the piece to be Symphony and so Elcock reorchestrated the work, changing it from all strings by adding woodwind, brass, and timpani in keeping with the Beethoven model.

The composer describes the mood of the pieces as ‘desperation in the teeth of impending tragedy’ and the ongoing tension of the work is one of its most fascinating aspects.

It will be fascinating to watch and listen for the rest of Elcock’s works, new and old, to appear. His distinctive voice has now spanned 10 symphonies, concertos, symphonic poems, and chamber music. He will be the invited composer at the end of May for the Elgar Festival in Worcester and will be in conversation with the Festival’s Artistic Director, Kenneth Woods.

Admin –

From Fanfare Magazine, October 2024

ELCOCK Violin Concerto1. Symphony No. 8 ? Kenneth Woods, cond; 1Zoë Beyers (vn); English SO ? NIMBUS 6446 (56:24)

Despite the fact that he didn’t have the opportunity to release these two works by master symphonist, Steve Elcock on his own Toccata Classics label, I would think that my esteemed confrere Martin Anderson must be feeling very pleased that a composer that he lifted from almost total obscurity into the consciousness of music lovers all over the globe has now seen two major as-yet-unrecorded works find their way onto one of England’s premiere labels, something that surely would never have happened without Anderson’s pioneering efforts on behalf of the Anglo-French composer.

The CD opens with Elcock’s Violin Concerto, which he actually began writing in 1996, in which year he composed its first movement. Some years passed before he wrote a second, but it was not until 2006 that he got around to the concluding movement, the impetus coming from an amateur orchestra that desired to perform the work in that year. If I heard the opening of this concerto blind and had to come up with the country of the composer, I’d guess “Romania.” My impression would be because of the melodic contour of the solo line, including its use of the augmented second, endemic to the music of that country. It was not long into the movement, however, that I heard more Elcock and less Enescu or Jora. About this work, the composer writes that he wanted it to recapture some of the “classical momentum” that had been largely lost from the Romantic era onward. I do indeed hear a Classical spirit throughout this piece (indeed, parts of it even have the flavor of a concerto grosso), but its harmonic underpinning is strictly Elcock in its diversity and complexity. Not only is the soloist kept very busy in this movement (as one would expect in any concerto), but the orchestra almost equally so.

The second movement begins with muted strings setting an undulating and rather Ravelian background over which the soloist spins out a lovely tune. Other instruments gradually enter and weave interesting lines around those of the violin, keeping the listener fully engaged in the work which is developed in the composer’s inimitable fashion. The considerably shorter finale is a passacaglia that gradually increases in tempo and vigor, the relative harmonic density of the opening eventually leading to a powerful, definite, and rather abrupt close.

Zoë Beyers plays with accuracy, verve, and a felicitous facility, but I wish that Nimbus had boosted her a bit. She sometimes gets lost in the portions of the piece that include a busy texture in the orchestration; even an increase of a couple decibels would have been sufficient. The significant reverberance of the recording doesn’t aid her audibility either, but otherwise I do not find it objectionable.

Elcock’s Symphony No. 8 also experienced an unusually long gestation period, given that the composer began it in 1981, some 15 years before his Symphony No. 1. I won’t go into the entire convoluted history of this work, but suffice it to say that Elcock is hardly the first composer to write his symphonies “out of order.” Penderecki completed his sixth venture into the genre well after his eighth, and the ordering of the numbered symphonies of Schumann and Mendelssohn corresponds only distantly to their chronology of composition. Thus, cast in a single 24-minute movement, Elcock’s Eighth begins with lines in the low strings, and builds up gradually over the next few minutes in rather Shostakovich-like fashion to a dramatic climax featuring the high strings. The short motifs heard at the outset are well developed according to the composer’s natural instincts whereby he creates compelling symphonic structure. The composer maintains a somber tone throughout, as though the Symphony were a harbinger of some impending cataclysmic event. In the end, though, it fades away to nothing via a trill in the second violins. Its conclusion is nothing short of indescribably beautiful.

Kenneth Woods and the English Symphony Orchestra provide a truly compelling reading, and the maestro captures every nuance written into this remarkable symphony. Composers salivate over hearing their music performed to such a high standard. The minor balance problem that I note in the Concerto is naturally not a factor in the Symphony. Elcock enthusiasts, of which I am one of the most dedicated, will not want to miss this arresting program, but if you are as yet unacquainted with his unique genius, you should definitely check this disc out, as well as the half-dozen Toccata Classics releases of the music of this seasoned symphonist. David DeBoor Canfield

Five stars: Another most welcome disc devoted to the orchestra music of an English/French master composer.

Admin –

American Record Guide. September 2024

ELCOCK: Symphony 8; Violin Concerto Zoe Beyers, v; English Symphony/ Kenneth Woods Nimbus 6446—56 minutes Steve Elcock (b 1957) is a self-taught Anglo-French composer who spent many years writing pieces seemingly consigned to the desk drawer. Recently the Toccata label took notice and released the first album of his music (Toccata 400, J/F 2018). Since then, several more releases have come our way and have revealed him to be a signifi-cant composer of serious, complex, and substantial classical music. This one is no exception.

His Violin Concerto (2006) is a true masterpiece of the genre—well paced, tightly crafted, and perfectly balanced, with plenty of imagination and substance in the writing for both solo violin and orchestra. The thrilling classical momentum of I gives way to a sweetly lyrical II, the soaring violin complemented by beautiful textures and color from the orchestra. The Rautavaarian dreamscape gives way to muscular, Nielsen-esque vigor with a passacaglia finale that culminates in one of the most explosively exciting climaxes I have heard in a violin concerto. This is a work that deserves to be heard on the world stage.

His single-movement Symphony No. 8 (1981/2021) began life as a string quartet; he rewrote it as a sinfonietta, then finally as a symphony for Beethovenian forces. The final result is a bleak, harrowing affair shrouded in a mood described by the com-poser as “desperation in the teeth of impending catastrophe”. It is driven by motives introduced in the first few bars, which are rigorously and intelligently developed across the piece in a language that contains fleeting elements of Shostakovich and Sibelius. It is a demanding but rewarding piece to the listener. The symphony comes to us as part of the 21st Century Symphony Project, Kenneth Woods’s initiative with the English Symphony to commission new symphonies by living composers—a laudable project that has already yielded some gems and further dis-plays the excellence of British composers in the symphonic genre. The performances on this disc are superlative, not least the excel-lent playing by ESO concertmaster Zoe Beyers. FARO

Admin –

ELCOCK Violin Concerto.1 Symphony No. 8 • Kenneth Woods, cond; 1Zoë Beyers (vn); English SO • NIMBUS 6446 (56:24)

Despite the fact that he didn’t have the opportunity to release these two works by master symphonist Steve Elcock on his own Toccata Classics label, I would think that my esteemed confrere Martin Anderson must be feeling very pleased that a composer whom he lifted from almost total obscurity into the consciousness of music lovers all over the globe has now seen two major, as yet unrecorded works find their way onto one of England’s premiere labels, something that surely would never have happened without Anderson’s pioneering efforts on behalf of the Anglo-French composer.

The CD opens with Elcock’s Violin Concerto, which he actually began writing in 1996, in which year he composed its first movement. Some years passed before he wrote a second, but it was not until 2006 that he got around to the concluding movement, the impetus coming from an amateur orchestra that desired to perform the work in that year. If I heard the opening of this concerto blind and had to come up with the country of the composer, I’d guess “Romania.” My impression would be because of the melodic contour of the solo line, including its use of the augmented second, endemic to the music of that country. It was not long into the movement, however, that I heard more Elcock and less Enescu or Jora. About this work, the composer writes that he wanted it to recapture some of the “classical momentum” that had been largely lost from the Romantic era onward. I do indeed hear a Classical spirit throughout this piece (indeed, parts of it even have the flavor of a concerto grosso), but its harmonic underpinning is strictly Elcock in its diversity and complexity. Not only is the soloist kept very busy in this movement (as one would expect in any concerto), but the orchestra almost equally so.

The second movement begins with muted strings setting an undulating and rather Ravelian background over which the soloist spins out a lovely tune. Other instruments gradually enter and weave interesting lines around those of the violin, keeping the listener fully engaged in the work which is developed in the composer’s inimitable fashion. The considerably shorter finale is a passacaglia that gradually increases in tempo and vigor, the relative harmonic density of the opening eventually leading to a powerful, definite, and rather abrupt close.

Zoë Beyers plays with accuracy, verve, and a felicitous facility, but I wish that Nimbus had boosted her a bit. She sometimes gets lost in the portions of the piece that include a busy texture in the orchestration; even an increase of a couple decibels would have been sufficient. The significant reverberance of the recording doesn’t aid her audibility either, but otherwise I do not find it objectionable.

Elcock’s Symphony No. 8 also experienced an unusually long gestation period, given that the composer began it in 1981, some 15 years before his Symphony No. 1. I won’t go into the entire convoluted history of this work, but suffice it to say that Elcock is hardly the first composer to write his symphonies “out of order.” Penderecki completed his sixth venture into the genre well after his eighth, and the ordering of the numbered symphonies of Schumann and Mendelssohn corresponds only distantly to their chronology of composition. Thus, cast in a single 24-minute movement, Elcock’s Eighth begins with lines in the low strings, and builds up gradually over the next few minutes in rather Shostakovich-like fashion to a dramatic climax featuring the high strings. The short motifs heard at the outset are well developed according to the composer’s natural instincts whereby he creates compelling symphonic structure. The composer maintains a somber tone throughout, as though the Symphony were a harbinger of some impending cataclysmic event. In the end, though, it fades away to nothing via a trill in the second violins. Its conclusion is nothing short of indescribably beautiful.

Kenneth Woods and the English Symphony Orchestra provide a truly compelling reading, and the maestro captures every nuance written into this remarkable symphony. Composers salivate over hearing their music performed to such a high standard. The minor balance problem that I note in the concerto is naturally not a factor in the symphony. Elcock enthusiasts, of which I am one of the most dedicated, will not want to miss this arresting program, but if you are as yet unacquainted with his unique genius, you should definitely check this disc out, as well as the half-dozen Toccata Classics releases of the music of this seasoned symphonist. David DeBoor Canfield