Reformist musicologists with a politically-correct worldview might find themselves raising an eyebrow at this week’s Surrey Mozart Players concert, where, with blatant disregard for all the latest scholarship, the orchestra and I will be playing Johannes Brahms’ “Variations on a theme of Josef Haydn.”

We will not be playing the now-ubiquitous “Variations on the Saint Anthony Chorale.”

Mind you, I’m not arguing against the wealth of research that raises serious questions about whether or not Haydn wrote the Saint Anthony Chorale. (or, for that matter, the Divertimento in which it appeared). Although scholars continue to debate the point, the question of who wrote the theme is not important to me in this case. What is important is who Brahms thought wrote the theme.

I’m not comfortable with re-naming a major work by Brahms simply because he was unaware of or misinformed about the actual provenance of the theme he was working with. (Perhaps, just to be completely upfront, we should put it in the program as “Variationen über ein Theme von Jos. Haydn”). Why? Well, it seems clear that Brahms was not just looking for a theme, but for a theme by Haydn. Brahms was a great classicist, who revered Mozart and Haydn above almost all other composers. In his opus 56, Brahms set out to write an affectionate homage to Haydn, and chose the Chorale because he thought it struck a useful balance between offering material that was well suited to the variation form, and embodying certain qualities typical of Haydn’s genius.

One of the most distinctive (and least understood) qualities of Haydn’s music is the incredible sophistication with which he organizes and disrupts musical time. Haydn’s approach to phrase structure, hyper-meter, harmonic rhythm and large scale metric instability is the most complicated, nuanced, sophisticated, original, inspired, witty and modern of any composer who ever set pen to paper. No other composer has ever made the unfolding of music in time so structurally interesting and coherent, yet somehow completely unpredictable.

Throughout Haydn’s music, whenever a theme sounds simple and foursquare, something unexpected is about to happen, or something mischievous is already going on.

Take the opening of the St. Anthony Chorale. The melody sounds like simplicity itself, but instead of falling into the balanced pair of four bar phrases one expects, it is actually a pair of five bar phrases. Haydn was the king of weird phrase lengths. Brahms takes the subtle musical joke of the foursquare tune written in five-bar phrases as pushes it about as far as humanly possible (for anyone but Haydn) throughout the piece.

This is why it bums me out when I go to concerts and see the piece listed (as it seems to be more and more) as “Variations on the St. Anthony Chorale.” That politically correct, blatantly point-making re-titling tells you nothing about Brahms’ motivations and intentions when he wrote the piece. Brahms wasn’t interested in St Anthony, he was interested in Haydn. Better to call the piece “Variations on a theme by Josef Haydn [Theme not by Josef Haydn]” if space allows and you’re really worried about upsetting Haydn aficionados who dislike the Chorale, and don’t want him associated with it. Otherwise, it seems like an exercise in calling attention to how clever the writer is, rather than trying to make clear what Brahms intended when he wrote the piece, which would surely do more to enliven the listening experience. By all means, address the confusion over the authorship of the theme in the notes if you think it is important (although I fail to see how it is more than an amusing curiosity), but let Brahms’ title stand.

Fortunately, it is rather rare to subject a major work of a major composer to a posthumous re-naming. If anything, it’s more usual to simply append a posthumous nickname, as in Mozart’s “Elvira Madigan” concerto. When I first heard of the piece, I assumed Elvira Madigan must have been some comely young pianist in Vienna who caught Mozart’s eye. How was I supposed to know that the piece had been re-named in honor of a 1967 Swedish art film? I suppose that, on principle, I oppose adding a nickname to a work written almost 200 years ago, but I still hold out hope that the music world will eventually start calling a Haydn symphony (I’m not picky about which one it is) the “Kenneth Woods.”

Even when it seems like re-titling is the obvious thing to do, things often go wrong, and important aspects of context are lost. Take the case of Dvorak’s ever-popular “String Quartet no. 12 in F Major, opus 96.”

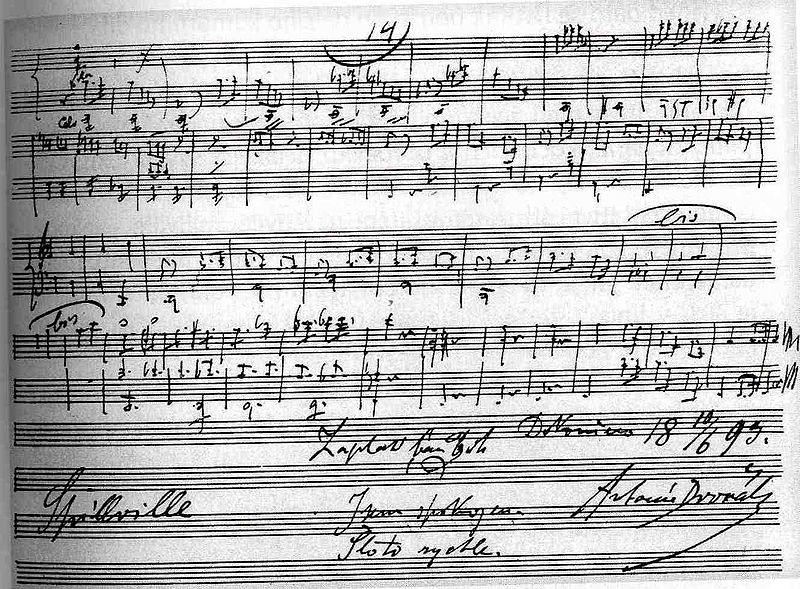

The last page of the autograph score with Dvořák’s inscription: “Finished on 10 June 1893 in Spillville. I’m satisfied. Thanks God. It went quickly”

If only Dvorak had left the name at that. You probably know this ever-popular gem of the chamber music literature as the “American” quartet.

As it happens, in early years the piece was known (apparently with Dvorak’s blessing) as the “Nigger” quartet. The name was still widely accepted into the 1920’s, as evidenced by this interesting Gramophone review of a recording by the Dyke Quartet (you can’t make these things up).

“Although the score of this most genial of quartets makes no mention of the title “Nigger,” describing the work simply as Quartet in F major, Op. 96,” there can be no doubt of the suitability of the nick-name by which it is generally known.”

Of course, “suitability” now seems a somewhat perverse word to describe the use, however innocently it was intended, of a word that has a unique power to serve as shorthand for hatred and racism. In this rare case, the name of the piece had to be changed – the original title is deeply offensive.

The problem in this case is not that the piece was renamed, but that it was renamed as the “American” quartet. Dvorak was not writing an “American”-inspired piece along the lines of Copland or Ives. He was writing a specifically African-American-inspired piece. By calling the piece “American,” modern listeners can miss out on how completely focused Dvorak was on the music and experience of black Americans. The old Gramophone review quickly outlines the self-evident reasons why Dvorak chose the original title for the piece:

“It was in 1892 that Dvorak went to America to take up a post in New York. The keen interest in folk-song and local colour which had already shown itself in his treatment of Bohemian music not unnaturally led him to the study of the American Negro tunes. Here, in the ” Spirituals ” and other songs, his genius found just that type of material that it could best turn to account. Everyone knows that these negro melodies and rhythms are the source of modern “Rag-time” and its derivatives, and it is interesting to compare Dvorak’s works in this genre, the New World Symphony, Op. 95, and this quartet, Op. 96 (both written in 1893) with recent efforts to adapt “jazz ” to the tastes of the cultivated musician. But there is one aspect of the matter that has been little dwelt upon. A glance at Kodaly’s arrangements of Hungarian songs or at Dvorak’s own “Songs my Mother Taught Me” shows us that the syncopation characteristic of the negro melodies was also a feature of the tunes of Dvorak’s own country. No doubt this had a lot- to do with his sympathy towards the American music. Incidentally, too, it disposes of the claim that the syncopated style is a unique product of America.”

The “American” Quartet remains one of the most popular works in the quartet literature, with young players and amateurs, in spite of the fact that, like most of Dvorak’s chamber music, it is damnably difficult to play in tune. I’ve taught it more times than any other quartet, with the possibly exception of Beethoven’s opus 18 no. 1 (also in F major, and also damnably hard to play in tune). It’s easy to say that nicknames and titles don’t matter, but in over 20 years since I first taught the piece, I’ve only once asked a quartet what the title “American” means and gotten any sort of an answer that included black people or black music in a guess at Dvorak’s inspiration. Genial hillbillies, friendly (white) farmers, country gatherings – yes. Recently feed slaves? No. They all get it wrong.

So – in my opinion it is right to change the name to something that is not hurtful and hateful, but preferably only to something that, without causing pain and distress to colleagues and listeners, still gives the audience a similar sense of what Dvorak was inspired by in this piece. Only in America could you delete the N-word from the title of piece and manage to give black people a raw deal in the process. Also, I think it’s ultimately healthy to face uncomfortable truths about musical history, rather than simply whitewashing the historical record. Researching this post, I was a little disappointed, but not too surprised, to find at least program annotator who was fired for mentioning the original title in a note (even though the reference was deleted before the note was printed). History teaches us more if it makes us uncomfortable with our past when it should.

Of course, at the end of the day, the piece sounds way more like vintage Dvorak, in all his Bohemioistiy, than like African-American spirituals and traditional songs. Nothing wrong with that. Brahms’ glorious Variations don’t really sound anything like Haydn, either.

UPDATE

From the “oh goodness, this proves my point way more than I wanted it proved” file…..

“Dvorák wrote this quartet in three days while vacationing in a small Bohemian colony in Iowa. He was surrounded by pleasant farmers, friendly priests, and generous housewives; this would be a good explanation for the simple character of the piece. Perhaps being away from home helped him forget about the conflits between the predominant Austro-German tradition and the new Nationalistic Bohemian tradition that he was trying to create. “

Inspired by generous housewives?!?!?!? In what way were they generous? Did they give him pies? Darn his socks? Rock his world?

Yes, according to this writer, Dvorak was inspired by the pies and needlework of generous Iowa housewives.

And not by black people….

Arghh……

I’m with you on this one, Kenneth. Brahms called it what he called it; seems like the end of the discussion. I also ran across an “Elvira Madigan” reference this past weekend and it irked me almost beyond comment, especially since there are going to be few in an audience who have even heard of the film, much less seen it! Now the Dvorak quartet: that is a stickler.

Iowans have made such a big deal of Dvorak’s association to Spillville that I have heard conductors state that he even wrote the ninth symphony here (even though his own date of completion indicates that it was finished in NYC). We can be proud that he chose to call a tiny village his home in the summer of 1893, but it is totally inappropriate to re-write history, or titles, or even the works of the masters. They wrote what they wrote, warts and all, until they decided for themselves to rewrite or edit. Of course that is another discussion entirely.

Really interesting article Ken. Completely agree about Haydn’s use of unpredictabilty and wit – surely qualifies him for a previous KW title, most underated popular composer!

Mahler 2 on Sat? BW

Wow, that Dvorak link is quite something.

Fascinating note, Ken. “Only in America could you delete the N-word from the title of piece and manage to give black people a raw deal in the process.”

In 1967, when Elvira Madigan was playing in the US, that Mozart theme (excerpt) was wildly popular on the radio, and you could not escape hearing it. I was in graduate school, and a purchaser of classical LPs and a regular attendee of classical concerts, and I had not heard that concerto before. The film popularized the concerto and introduced many of us to part of Mozart we had previously missed out on.

Today, I agree that the film reference is passe, and might deserve a passing reference in program notes, but certainly not as an alternate title.

I agree about the Brahms, but have some problems with your comment on Dvorak’s Quartet.

The main problem is that this piece is far from being so utterly related to his experience of African-Americans. If you want to really hear that in a Spillville piece, try the original piano version of the American Suite. The last movement of the Quartet reflects in almost visual fashion his rail-fan experience — boy, did he love trains, and that is one of the most “train-ish” pieces that exists. And the beginning of the New World finale is also quite “train-ish”.

Then the quartet’s slow movement is his expression of the loneliness he experienced in the wide-open spaces as expressed in one of his oft-quoted letters back to Bohemia.

And other musical expressions of his experience in Spillville are related to an Indian wild-west show that came to town while he was there.

By the way, if you have never been to Spillville — and my wife and I have made a point of visiting there — please make the effort. It’s in the northeast corner of Iowa not far from Decorah. It warmed my heart to sit where “Mr. D.” (as my students one summer called him) sat to compose down by the Turkey River.

Re Paul’s comment about ‘train-ishness’ in Dvorak, yes! It was a long train journey (? 36 hours) across a dry Pennsylvania (no beer available) to Calmar, the nearest station to Spillville. If the last movement of the Spillville (American) quartet is motoric, what about the Scherzo of the quintet he wrote straight afterwards? I am not familiar with Kickapoo drumming, but surely that is also a train rhythm, and by consensus one of the best Scherzos he ever wrote. What about the wind-down of the quintet’s first movement with its major/minor alternation overlapping on different beats in the different parts – a steam engine coming to a stop?

Even in the 1920s Dvorak’s F major Quartet was known as the “American” Quartet, at least in America itself. A periodical of the time, the Phonograph Monthly Review (considered to be the American equivalent of Gramophone Magazine), in reviewing a Victor recording of the piece by the Budapest String Quartet in its issue of May, 1927, stated, “The Victor Company shows excellent taste in labeling the work – as correctly should be done – ‘American’ Quartet, instead of the title ‘Nigger’ Quartet in extensive use abroad.”

Hi Bryan-

You’re quite right that there are early examples of usage of the more polite title, but the point of my essay is that he polite title whitewashes (forgive the pun) the fact that the piece’s inspiration is African American in origin, not caucasian.

Well, I’m unable to find any evidence that when the F Major Quartet was new, when it was referred to in the United States with a nickname at all, said nickname was anything other than “American.” The use of the N-word to denote it seems to have been a strictly British phenomenon, one that they kept well into the 1950s. I don’t think this negates the point of your essay, but it does change the perspective a little. It suggests that the British were willing from an early time to acknowledge the African-American influences on the work (albeit with an offensive word), while those in the USA responsible for the work’s promotion (publishers? music critics?) were not…and that the British adopted the “American” nickname only after the offensiveness of their preferred one was impossible to ignore.

Elvira Madigan. The most famous film that nobody has ever seen.

Hello! I am most interested in the portion of the article regarding Dvorak’s American Quartet. I have performed this piece several times as a violinist and violist, and also found that their description of “American†was not what Dvorak intended. Before reading this article my friend told me that it was called the N-word quartet because of his sympathy to African-Americans. I have very little knowledge as to how people reacted to Dvorak’s “N-word†quartet.

I didn’t know he intended that title for a positive reason by acknowledging their influence in music in America. I’m wondering what we’re the negative backlashes if he had any?

Please don’t say that Elvira Madigan was “the most famous film that nobody has ever seen.” I am somebody, as are others of my generation. I think that the film popularized the music of Mozart among those who would not have thought they liked it. As a musician even at that time, I was thrilled that Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 21 was once again a popular hit.

As for the Dvorak String Quartet Op. 96 in F Major, I’d also like it to be re-named the African-American Quartet. In dropping its offensive moniker, its influences are lost.